Gadchiroli, Maharashtra: This is the story of Parasvihir, a village of one household of five people and how they gained legal rights to what are called “minor produce” and management of nearly 144 hectares—the equivalent of 269 football fields—of forest in a remote corner of Maharashtra.

With growing evidence (here, here, here and here) that Indian economic growth is not producing enough jobs for those who live off the land, the story of Parasvihir indicates how this uncertainty and insecurity could be addressed in great measure: by providing legal rights to more than 200 million in about 170,000 villages who depend on forests spread over 85.6 million acres—the size of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar combined—while keeping intact India’s fast-disappearing forests.

It was in 2016 that the head of the family, Varlu Kolu Uikey, 55, a Gond Adivasi from one of the world’s largest tribal groups, who lives in Parasvihir in Dhanora taluka in this eastern Maharashtra district, received what is called a “community forest rights (CFR)” title to the area in question. The state government also approved his claim for “individual forest rights (IFR)” over 2.17 acres, where his family can grow agricultural produce of their choice.

Uikey never went to school, like so many forest dwellers. Less than 60% of Adivasis, who make up a large proportion of forest dwellers, were literate, 14 percentage points below the national average, according to the 2011 Census, the last available data.

One of Uikey’s two sons has a fourth-standard education, and one of two daughters never went to school. Another son is studying BA, and another daughter studied till the 10th standard. No one in the family has held a job, and there is no prospect of one near Parasvihir.

“The recognition of community rights has allowed our family to access, harvest and sell minor forest produce to anyone of our choice,” said Uikey. “And it’s improved our financial condition.”

The minor produce that forest dwellers like Uikey can access includes all non-timber plants, such as bamboo, brush wood, cane, tussar, cocoons, honey, wax, tendu leaves, medicinal plants and herbs, roots and tubers. They have management rights to protect, regenerate, manage or conserve any forest resource for “sustainable use”.

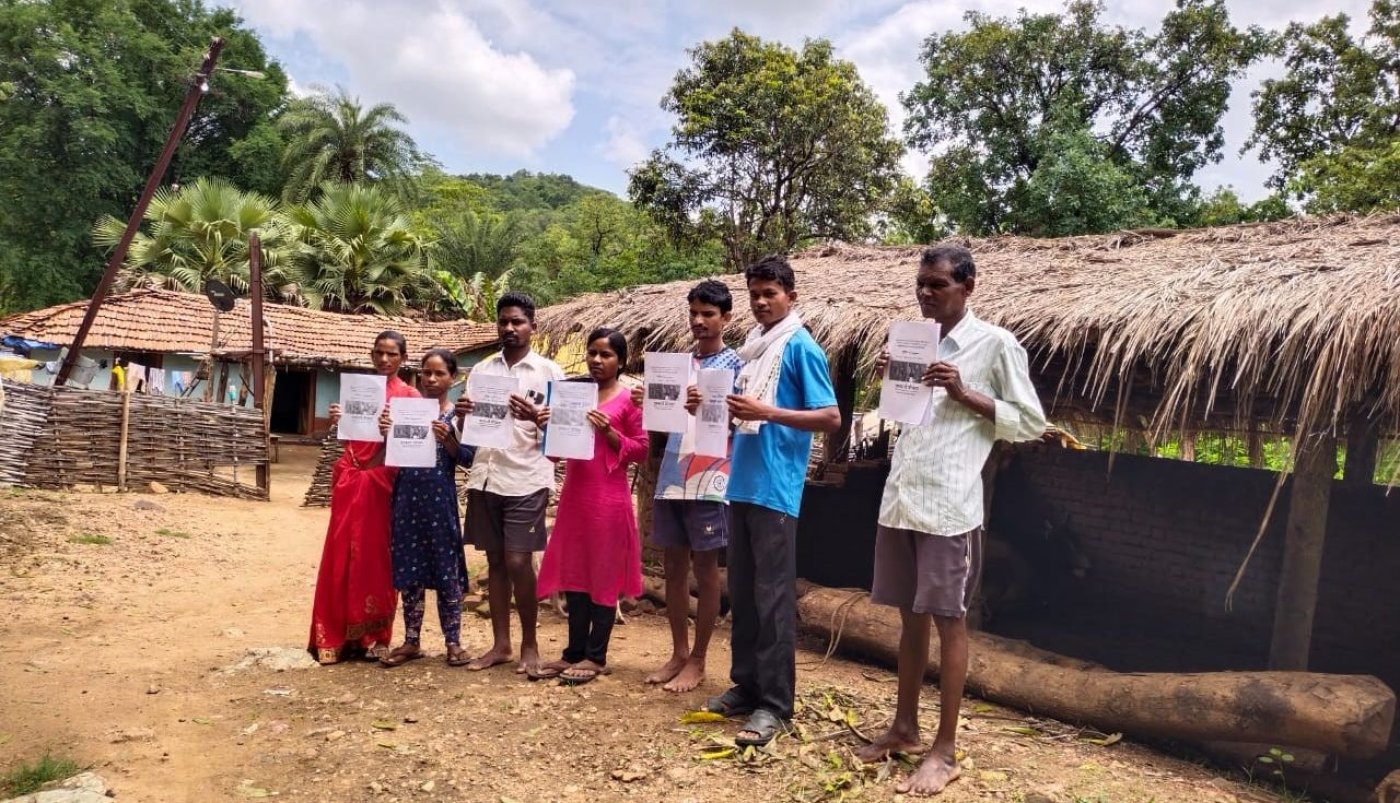

The self-belief of the Uikey family appears to be the most productive asset they own today. Following the example they set, other single-household villages in Gadchiroli district also claimed their forest rights. Today, three other villages with one household have received CFRs in the district.

We explain the process leading to the recognition of CFRs, developments after that and the lessons from Parasvihir for other villages nationwide in similar quests under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, better known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA), the law meant to formally secure land and livelihood rights for about 250 million tribal communities or others who traditionally depended on forests.

Reluctance To Implement The FRA

The FRA sought to reverse “historical injustice” of the colonial era (here and here), which saw forest-dwelling communities as encroachers on the land they used and lived on.

Forest dwellers who have lived in and depended on any type of forest land on or before 13 December 2005, can claim individual or community forest rights to protect, regenerate or manage forests, to live in or on which to grow food for themselves, graze cattle, fish, own and harvest “minor forest products” traditionally collected within or outside village boundaries for “sustainable use”.

While processing the claims for these rights, especially community forest rights, government agencies cannot insist on specific evidence or specify the number of households in the village that depend on the forests in question. To insist on doing otherwise is to go against the spirit of the FRA, which never intended members of the implementing agencies—the forest rights committee at the level of the gram sabha, the sub-divisional level committee (SDLC) and the district-level committee (DLC)—to have unfettered rights to accept or reject claims without due process.

The grant of such rights is especially significant at a time when old-growth forests are being cut down for mines, dams, roads, violating rights and processes under the FRA, documented extensively by independent reports (here, here and here) and media reporting (here, here and here).

In July 2022, India’s environment minister Bhupender Yadav claimed that the legal rights of millions of Adivasis had not been diluted in new changes to procedures that govern how forests are given to industry. But as Article 14 reported in September that year, doing away with the Centre’s responsibility to verify tribal rights had been the environment ministry’s intent since 2019.

The potential of a CFR land title can be vast and course-altering for a particular village, as we have seen in many villages across the country (here, here, here and here), boosting their livelihood and local management of forests.

Yet, given the pressure from industry for forest land, only about half, or 2.23 million of 4.44 million FRA claims for individual and community rights had been granted till June 2022, The Hindu reported in December that year, quoting government data released to Parliament.

State agencies nationwide have been rejecting (here, here and here) and have been reluctant (here and here) to process community forest rights claims on technical and procedural grounds.

Agencies implementing community FRA rights were meant to think beyond their subjective satisfaction over the ability of communities to manage their forests and the number of forest-dwelling households or communities in such areas.

In Parasvihir village, as our visits and interviews with key stakeholders between January and July 2023 revealed, implementing agencies followed due process in scrutinising and recognising the community forests rights’ claim of the village and did not question the number of households claiming these rights, which were recognised in 2016.

The Loneliness Of Parasvihir

The household of Uikey, the head of the sole Parasvihir household, is a microcosm of millions who have no clear or conventional sources of income or jobs and have traditionally depended on forests for livelihood.

There is a mud road, and it is almost impossible for outsiders to find their way to Uikey’s home deep in a forest in the Salebhati gram panchayat or village council, of which Parasvihir is a part.

Uikey’s house has electricity but no toilet, and he is not part of the efforts of the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, the Prime Minister’s Housing Programme, which was to deliver a proper home to each rural Indian by 2022

Uikey’s home uses water from an open well nearby. With no conventional source of income, the family collects and sells forest produce. Earnings vary depending on what grows and what they collect. They grow some paddy, but that is for their own consumption.

Uikey’s family is officially recognised as being below the rural poverty line. He has a below poverty line (BPL) card and collects ration or subsidised food from the Salebhati gram panchayat, a walk of 4 km.

The forest department provided the Uikeys with a gas connection in 2022, but since the closest gas agency is 10 km away in the neighbouring village of Dhanora, the family depends on fuelwood to cook.

The Benefits Of Legal Rights

As the FRA rules required, Uikey’s gram sabha constituted a community forest resource management committee on 4 December 2016 and opened a bank account in its name at the Central Bank of India, Gadchiroli, after the family was granted FRA rights. He visited neighbouring Dhanora to learn about trade in the kendu leaf, which the family has harvested since 2016 and is used to make bidis.

In addition to recognised IFR land, which Uikey was farming before he received legal rights to it, he owns three acres of revenue or non-forest land within the village boundary. The two sons, 26 and 20, and two daughters, 32 and 28, help Uikey in growing paddy or collecting forest products from the 144 hectares over which they now have community forest rights. Manure from six cows, four oxen and nine goats is enough to fertilise the thin soil of his farmland.

Since there are no daily wage workers available, he bought a tractor for Rs 500,000 with a bank loan and a motorcycle for emergencies.

Uikey and his family said a recognised CFR title had myriad benefits. No one from the family had looked for employment since, no one had migrated, and land productivity had improved. They were relieved, they said, from their previous ordeal of worrying about work.

He talked enthusiastically, explaining how his family members had consistently benefited from the recognised CFR areas over the last seven years.

“No one from my family has looked for employment since we got these rights, no one has migrated and the productivity of our land has increased,” said Uikey. “We are relieved. We don’t have to worry about finding work.”

In 2016, the year their claim was recognised, the family collected and sold forest produce, especially kendu leaves and bamboo to a contractor, earning Rs 56,336. Their income fell to Rs 15,983 and Rs 25,810 over the next two years, before recovering to and stabilising at Rs 50,445 in 2019. The pandemic did not adversely affect their income, which was about Rs 50,000 in 2021 and Rs 45,000 in 2022.

Since the family could not find labour to collect Kendu leaf from all over their allotted area, they engaged neighbours from nearby villages, paying them daily wages. This provides employment to their neighbours, who otherwise had to search or migrate for work.

How Uikey Claimed His Rights

The FRA, as we said, does not require a specific number of households to live in a village to get forest rights. Claimants must submit their claims with more than one piece of evidence to claim both IFR and CFR from a list of such evidence in section 13 of the FRA Amendment Rules 2012.

Uikey learned of the FRA in 2014 when he attended a gram panchayat meeting in Salebhati. Devaji Tofa, a local tribal leader, considered by many as a role model for his selfless work in advancing tribal rights in Gadchiroli, supported Uikey’s IFR and CFR claims.

Uikey filed IFR and CFR claims over 2.17 hectares and 143.97 hectares of forest in 2014 with evidence. He submitted a nistar patrak, a letter from the revenue officers of the village and panchayat office, as evidence of his IFR and CFR claims. They certified his claim that the family farmed and depended on the forest land before 13 December 2005.

The gram sabha, which comprised the five members of the Uikey family, passed the resolution and forwarded the claim to the SDLC (the sub-divisional level committee) for verification. The SDLC passed his claim, accepted the evidence and forwarded IFR and CFR claims to the DLC (the district-level committee), which recognised both claims in 2016.

The title recognised the exclusive rights of Uikey’s family over minor forest produce, grazing, fishing and other products of water bodies, and rights to protect, regenerate, conserve, or manage the “community resource” over 143.97 hectares in two swathes of land within the revenue boundary of the village.

The Pressures Of Success

Uikey’s family may have got their community right, but they have found that they must face a variety of challenges to keep them.

The elite of neighbouring villages often exploit the resources of Parasvihir’s forests without informing the Uikeys, who cannot patrol or monitor their forests. The district administration has shown no interest in dealing with these problems.

Instead, government officials, especially from the forest department, told him that the recognised CFR would be withdrawn if he could not protect it

Help has come from SRISHTI, a local NGO working on rural development and livelihood issues in Gadchiroli. Since November 2022, SRISHTI has helped the Uikeys demarcate their CFR, map the forest and biodiversity resources, build linkages with neighbouring villages and prepare a community forest resource management plan.

Uikey hopes the district administration will support his village’s CFR management plan and provide financial, institutional, and technical assistance under what is called the district convergence plan, under which all department schemes converge with the land of forest rights titleholders to make it more productive.

Lessons From Parasvihir

The first lesson from Parasvihir is that institutional support is central to enforcing the FRA, irrespective of the size of the village claiming community forest rights.

For community forestry to achieve environmental and economic gains, the rights of communities over recognised land clearly require institutional backing. While SDLCs and DLCs nationwide often, whimsically and arbitrarily, reject community rights’ claims, the case of Parasvihir indicates how local State institutions, from panchayat to district collector, can create an enabling environment, and provide documentary, technical and institutional support.

The size of the Parasvihir village did not stop the SDLC and DLC members from processing and recognising the CFR claim of one household over 143.97 hectares of forest. The provisions of FRA prescribe that all types of claims under the Act be verified fairly and impartially.

Eventually, the case of Parasvihir is notable because of Uikey, his determination to learn how to file claims with help from his neighbours, with no support initially from NGOs or other support groups, and then follow through in acquiring the rights.

While the Uikeys’ determination is apparent, it is the State that is primarily responsible for enforcing the law in letter and spirit to undo historical injustice to India’s forest-dwelling communities. Many have spoken of the mindset change required among administrators nationwide if the FRA is to be implemented in letter and spirit. Hopefully, they can all learn from Parasvihir.

(Vishnukant Govindwad is a PhD scholar and Geetanjoy Sahu is a professor at the Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.