Bengaluru: Somewhere in U’s studio, a large, sophisticated machine laboriously cranks out a banner for Shri Ram Sene Hindustan, a fringe Hindu right-wing group in north Karnataka

“This year, Ganesh Chaturthi and Eid were on the same day. We are printing banners alternatively from these machines,” said U, a Muslim and self-taught designer.

“We print whatever our clients want. We can print Shivaji posters in one machine and Aurangzeb's in another,” he said, laughing.

Seventeen years ago, his then-fledgling design studio was approached by a prominent local doctor to design a poster protesting the celebration of the demolition of Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992 as “Vijay Diwas”.

U chose the image of kar sevaks (Hindutva activists) climbing the dome of the 500-year-old mosque. Underneath, the caption read: “Our struggle for final and complete supremacy of Allah involves Babri Masjid too.”

U believed the caption served as a reminder to the kar sevaks that their actions would be judged by God.

The posters were plastered at bus stands and shops in Bijapur, a heritage town located some 200 km from U’s studio.

Quickly, Hindu right-wing organisations declared that this was the handiwork of the Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), a banned right-wing Islamic organisation.

Police action soon followed.

U’s retelling is seized by a sudden energy.

“How many cases can the state file for a six-by-eight-inch pamphlet? Six cases, accusing us of terrorism.”

Fifteen people, including a juvenile and five Hindus who ran a printing press, were arrested for being “members of SIMI”.

Charges of sedition and Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) were invoked.

A decade later, U was acquitted in four of the six cases filed.

The proceedings in the remaining two cases arising from the same incident, involving the same investigating officers, charges, and evidence, remain stuck in lower courts.

Seventeen years after the posters went up on the walls of Bijapur, U still makes his way to the lower court every month.

Terror Law Weaponised Against Muslims

U is among the 925 persons accused under UAPA in Karnataka since 2005.

Data, researched and produced at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, over three years, shows the extent to which the UAPA has disproportionately targeted Muslims.

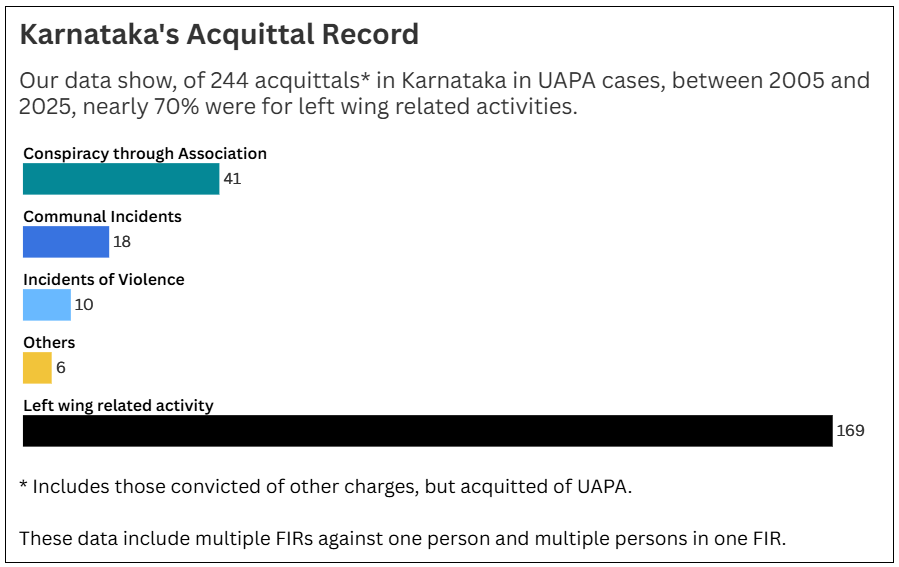

In the first part of the four-part series, we reported that of 925 accused, 783 were Muslim, with nearly eight in 10 persons accused under the UAPA during the BJP’s 10.5 years in power.

Karnataka has experienced nearly equal periods of rule by the Indian National Congress (9.09 years) and the BJP (10.5 years), as well as a period of President’s Rule of 226 days. The Janata Dal (Secular) was in coalition with both parties intermittently over the past 20 years.

In the first part, we reported that the number of acquittals was five times higher than the number of convictions (244 persons acquitted versus 46 convicted). Of these, 169 acquittals were in cases of left wing activities.

In the second part, we examined the political and communal uses of the UAPA in Karnataka. In the third part, we showed that 80% of convictions under UAPA in Karnataka came from guilty pleas instead of full trials in the past 20 years.

The Long Road To An Acquittal

In this fourth and concluding part, we examined acquittal judgments for 75 persons charged under the UAPA for conspiracy, communal or partisan incidents, violence, or other offences, such as making or distributing counterfeit currency.

As we reported in the first part, for incidents involving left wing related activities, the challenge was that many of the accused remained at large for years. This means many cases were never committed for trial, making them difficult to find for the database.

Over the years, as many accused surrendered or were found, the trials of these cases—even if the incident was a decade old— resumed. This also meant that, in our analysis of outcomes, these individuals were not unique, as multiple cases were filed against a single person. (The highest was at least 34 FIRs filed against one person for left-wing related activities).

Here we analyse 75 acquittals across incidents other than left wing related activities. We found that lapses in investigation and allegations of police impropriety feature in acquittal judgments by the trial court or the Karnataka High Court.

Of the 75 acquitted, 69 (92%) were Muslim.

In 82.67% of acquittals, independent witnesses (i.e., non-police witnesses) contradicted the prosecution's account of events.

In nearly a third of these cases, the panch witnesses, who are called upon to verify the arrest of the accused or the police's recovery and seizure of evidence, turned “hostile”. These witnesses have denied ever seeing the police make recoveries or have admitted to blindly signing documents submitted by the police.

In one case, the panch witnesses admitted to signing more than 20 documents in a single day without reviewing their contents.

Blemishing the credibility of the panch witnesses is a key component of the defence arsenal.

In multiple orders, they’ve successfully shown that panch witnesses were doctored, tutored or worked closely with the police or have had political links.

“Once the police make up a story of a terror conspiracy, they don’t back down. They’ll keep adding layers to that story even if the proof is not there,” said Iqbal Jakati, who spent more than three years in prison under UAPA charges before being acquitted.

He is one of the few who talked to Article 14 on the record.

At the time of the arrest, he was an automobile salesman. Since his release, he has become a prominent local journalist.

He and 14 others were arrested in 2008, accused of being members of SIMI operatives, attempting to create bombs that would cause communal disharmony in Belagavi, and recruiting people for their cause of Jihad.

“It all started because the police found some videos of the war in Afghanistan on someone’s computer (the main accused),” said Jataki.

From there, they arrested everyone he interacted with, particularly those who were in the local football club with him.

“We used to hang out after playing football, and the police made it seem like this was a terror conspiracy meeting,” said Iqbal.

Iqbal’s bail was rejected twice, and he was released from prison only in 2011, when the trial court acquitted all the accused.

“The police said they found incriminating videos on the computer. One video they played was a speech about visiting Ajmer for ziyarat (paying respects to those interred at a dargah.) But police claimed the video was about going to Ajmer for Jihad,” he said.

“That’s the sort of flimsy evidence they had on us. It was enough to deny us bail,” he said.

The court order said that the only evidence of a terror conspiracy was “voluntary statements” of the accused during police custody. Among the evidence presented was a wrist watch, which the police claimed was hidden in a banana and smuggled into a prison to make a bomb.

No witness, not even on the prosecution side, supported this claim.

In five judgments, leading to the acquittal of 31 persons, judges called investigations “shoddy”, "improper” or “suspicious”.

Serious lapses pointed out by the court include: inordinate delays in sending explosives for forensic testing; inability to present material evidence of recoveries of arms and bombs despite its mention in the chargesheet; attempts to present everyday items, such as plastic containers and wires, as materials to make bombs; to even not translating Urdu and Arabic literature which police have claimed was “jihadi” literature.

Furthermore, in six out of 13 acquittal judgments, the police did not seek sanction for investigation under terror charges from a high-ranking official within the home department as mandated by the law.

The courts deemed the UAPA charges as being without “a valid sanction”.

Trapped In A Never-Ending Web

The interconnected web of UAPA cases ensures that those arrested can stay in prison for years even after hard-fought acquittals.

An accused in one case may be charged with similar conspiracies in other jurisdictions.

In 2008, Karnataka police claimed to have busted three SIMI modules in northern Karnataka.

In January, 18 people were charged for being part of the Huballi module; in May, 15 persons, including Iqbal and three others from the Hubballi module, were charged as part of the Belagavi module. In December, when the posters against the demolition of Babri Masjid went up, the police went in search of SIMI links.

“The police kept reeling out names of people they said were from terror organisations,” said U, recalling intense interrogations in police checkposts and abandoned buildings during this time. “They would say: “We know they came to your house for lunch. What did you feed them?”

“They would show pictures of those accused in Hubballi and Belagavi cases and try to find a link through some family member or mosque,” he said.

The “Bijapur module” could not be linked to the larger SIMI conspiracy. But, those arrested in Hubballi and Belagavi were soon linked to “SIMI” cases across the country: holding conspiracy meetings in Madhya Pradesh, holding terror training camps in Kerala and bomb blasts in Gujarat.

An acquittal in the Hubballi or Belagavi case meant little, as they had to wait for the culmination of other cases.

For some, like the prime accused in the Hubballi case, it took a decade.

Others remain caught up in the web of cases.

‘It’s Like A Sword Hanging Over My Head’

“I’ve been in jail for over nine years. On and off. Each time I get acquitted, I get pulled into another jail on another case,” said Y, 41, acquitted in the Belagavi case and out on bail in another terror case where he was convicted of being involved in a SIMI-linked conspiracy.

Details of his case or any identifiers are being withheld on his request.

It’s been nearly a decade since he was acquitted in Karnataka, but he awaits judgment on his appeal in the second case.

Y grew up in a family with deep roots in the Muslim community in a small town in Karnataka. In the mid-2000s, he was caught up in a personal tragedy when a loved one was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He frantically visited doctors, religious leaders and faith healers.

“I was desperate. If anyone told me they could have a cure, I’d go there. I’ve travelled across central and southern India for this,” he said.

In 2008, the Karnataka police’s narrative of the Hubballi and Belagavi SIMI modules revolved around doctors and medical students indoctrinating Muslims into jihad. Y was soon in the dragnet: not only here, but also in other modules headed by religious leaders whom he reportedly visited.

Y wasn’t the prime accused in either of the two cases in which he was accused.

In the Hubballi case, court documents show that none of the 278 witnesses examined identified alleged illegalities by Y.

In the other case, the primary accusation against Y is that he attended one of SIMI's public meetings.

“It’s like a sword hanging over my head. I’m just viewing each day out with my family as a blessing. I don’t know what will happen tomorrow,” he said.

Where Process Is The Punishment

On 9 September 2012, the Bengaluru police claimed to have received “credible information” that “people of India-Bangladesh border (sic)” were carrying counterfeit currency at a lodge near the central railway station.

Six persons were arrested, and police reportedly seized arms, ammunition, and over Rs. 16 lakh in large denomination fake currency.

The aim of this unnamed “terror group” was “to create criminal disturbances and unrest in the country”.

A few hours later, Z, a 41-year-old Hindu, and his friend arrived at the lodge.

“My friend trades old gold. He got a call saying there was a seller at the lodge. I thought I’d use this as an opportunity to distribute invitation cards for my sister’s wedding to a few relatives in Bengaluru,” he said.

Z, who carried along a bag full of invitation cards, and his friend were led to a dingy room in the lodge. A verbal transaction was finalised, and the gold would be delivered by the seller to his friend later in the day.

When they stepped out, two police officers in civilian clothing surrounded them and escorted them to the police station. Z was forced to sign a register and was given a piece of paper that appeared to contain a cryptic code.

From there, it was the police station, an appearance before a magistrate and prison.

“Some friends in my village put me in touch with a lawyer. I read out the slip to him, and he told me that we were accused of being terrorists. My brain went blank. I just couldn’t understand this,” he said.

Z had been charged with using counterfeit currency, criminal conspiracy, possession and use of firearms and committing a terrorist act.

They were among 29 people from three states implicated in the “pan-national” conspiracy: Hindu merchants from Andhra Pradesh, Muslim construction workers from West Bengal, and local traders.

In a 2023 deposition before the judge, the investigating officer claims that Z and his friend accepted counterfeit currency.

Z was released on bail in 2014.

But, since then, he’s had to go to the special court of the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in the Bangalore district court, where UAPA cases are heard, nearly every month. It was here that he met the other accused.

As the hearings progressed, he came to a realisation: “The men we met at the lodge, the men who took money from us, were not among the accused.”

The case crawls in court: there is a hearing once a month, on average, Bangalore district court orders show.

The arms reportedly seized have yet to be presented before the court. Witnesses, whom the police had called to attest to the seizure of the currency or arms, have disputed the police’s claims or are unable to identify the accused with certainty.

Just 14 of the 29 initially arrested continue to attend the trial: 15 have died or have had their charges dropped.

Section 19 of the NIA Act provides that a special court shall hear matters on a day-to-day basis. But none of the cases whose court dates were examined by Article 14 involved a day-to-day trial.

“You have hundreds of accused being heard in just one special court. It is impossible to conduct day-to-day trials,” said S. Balan, a Bengaluru-based lawyer who has handled several UAPA cases.

“Once a UAPA charge is stuck, the system will ensure it remains with you for a long time.”

Z was 28 when he was arrested. He had a steady job, wanted to get married in a year, and had ambitions to build a proper home for his widowed mother and intellectually-challenged brother, who depended on him.

He’s now 41, unmarried and living in a one-room dwelling.

“No one wants to marry a man accused of being a terrorist,” he said with an apparent resignation in his voice. “I won’t get my time back, nor can I change my future. This case has ruined my life, no matter the outcome.”

Fourth of a four-part series. Read Part I here, Part II here and Part III here.

Names of those interviewed have been withheld on request.

Credits:

Investigative reportage, data mining, research & analysis for Karnataka, Mohit Rao; All India data mining and analysis, Sakshi R., Nikita B; Research on acquittals in UAPA in Karnataka, Zeba Sikora; Background research, Vibha S.; Research Direction, Lubhyathi Rangarajan; Principal Investigator, UAPA Data Series, Mayur Suresh; Edited by: Betwa Sharma.

This data is produced by a research project at SOAS, University of London, funded by the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.