Gurugram (Haryana) & Pithoragarh (Uttarakhand): In April 2016, Pijush Kanti Roy, a Kolkata-based senior manager at Tata Motors Insurance Broking & Advisory Services Limited (TMIBASL) discovered that his company’s chief executive officer (CEO), Tarun Kumar Samant, had been appointed on the basis of an apparently forged degree from Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh.

According to rules framed by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI), it is mandatory for a “principal officer” of an insurance broking firm like the TMIBASL to be a graduate.

Roy raised the issue with the company’s senior management and then escalated it to the heads of the Tata group, Cyrus Mistry and Ratan Tata, through email messages to their official addresses (copies of which are with these writers.).

On 5 August 2016, Roy’s services in the company were terminated on grounds of “insubordination.” He sought legal redressal of his grievances. He alleged that he instead faced retaliation from his employer.

In May 2018, TMIBASL’s chief financial officer (CFO), Bhanu Sharma, accused Roy of cyber-spoofing, claiming that he had created fake email identities to tarnish Samant’s reputation.

Roy was arrested on 21 May 2018 and jailed for 51 days.

In his email messages, Roy pleaded innocence and argued that the charges against had been “concocted” because he blew the whistle on his former boss. We reached out to Samant who is now an advisory board member in a business process outsourcing (BPO) company.

In a phone conversation with one of the authors of this report, Samant declined to comment on the case. When this story was published, he had not replied to a questionnaire sent to him over WhatsApp. We will update this story if he responds.

Roy has alleged in his email messages to the heads of the Tata group that he and family members had become “mental wrecks” because of the “false charges” levelled against him, and that he had been bankrupted because of complaints and legal cases in courts of law in different parts of the country: Kolkata, Mumbai, Delhi and Roorkee, Uttarakhand.

Roy said the cases against him were under adjudication and he would not like to say anything to us.

In May 2017, a year after Roy’s termination from TMIBASL, IRDAI confirmed that Samant’s degree was invalid and directed that he be removed immediately from the company.

On 15 May 2025, we emailed a detailed questionnaire to M Ravichandran, managing director and chief executive officer of Tata Motors Insurance Broking & Advisory Services Limited. There was no response. If there is one, we will update this story.

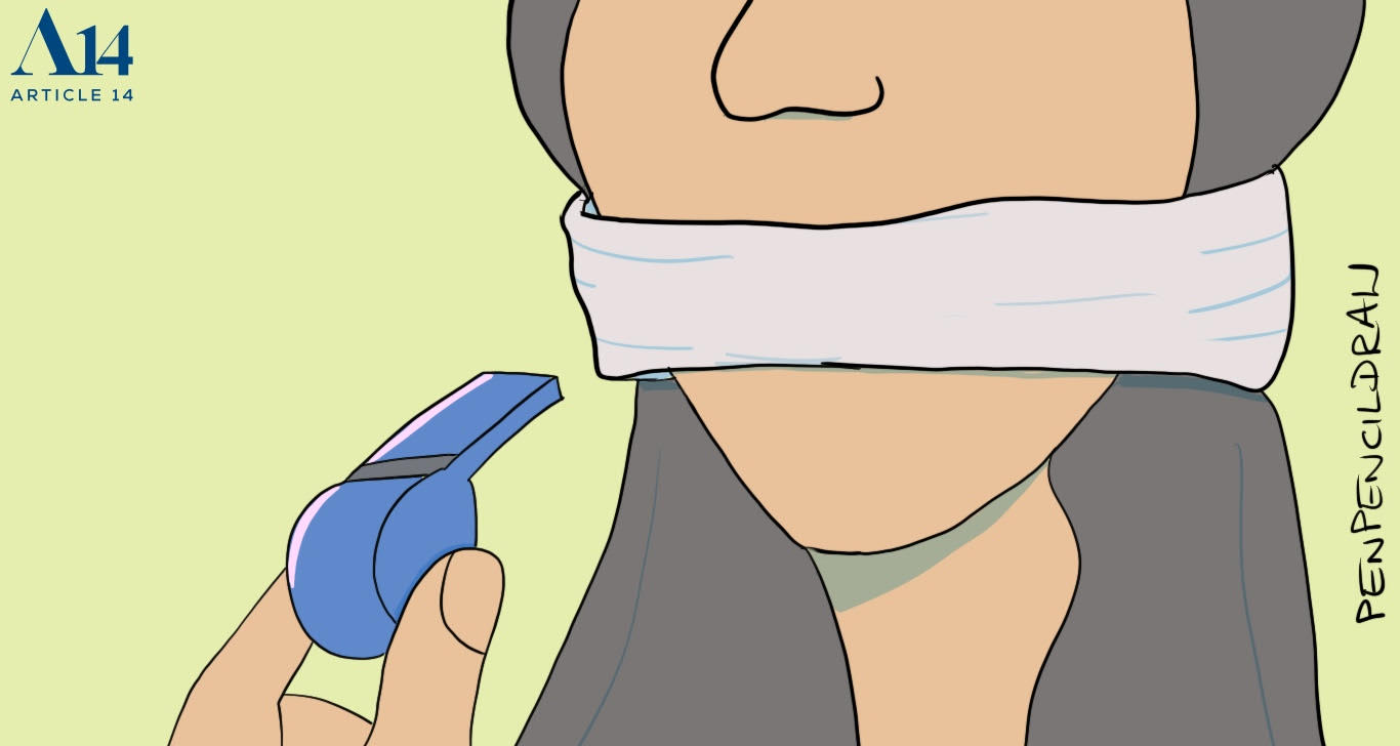

Punishing Whistleblowers

Roy’s story is one of three such accounts from whistleblowers in prominent Indian companies that we investigated. These stories reveal how systems meant to take corrective action instead turn against those who reveal corporate malpractice—and how the law offers no protection.

These three stories point towards a distinct trend in corporate India: whistleblowers who expose corruption are punished while the guilty escape the consequences of their actions.

All three sought to bring out corruption in the organisations that had employed, or employs, them. The consequences were that they were fired or endured punitive transfer orders, legal harassment, and attacks on their reputation.

Their experiences are reminders of how personal integrity or even naïve foolhardiness can exact a steep cost in India's corporate world, including in conglomerates with a reputation for probity.

Across the world and in India, whistleblowers can play a vital role in exposing corporate misdemeanours and safeguarding institutional integrity.

On 15 May 2025, The Economic Times reported that IndusInd Bank launched an internal probe into a series of past accounting reversals that had been flagged by a whistleblower in a letter sent to the Reserve Bank of India and the bank’s board of directors.

The whistleblower pointed out inaccuracies in calculating the bank’s interest income from microfinance loans, an improper relationship between a senior executive and an employee, alleged a Rs-600-crore discrepancy in interest accrual and claimed the bank had deliberately inflated its income.

The allegations by the whistleblower in IndusInd Bank are currently being investigated by forensic auditors and external firms.

Rather than being protected for upholding integrity and lauded for exposing malfeasance, many Indian whistleblowers face retaliation, legal harassment, and professional ruin, as others have pointed out before (here, here, here and here).

Confirmation Of Forgery

Nine years after he was sacked, Roy’s case reached the Central Information Commission (CIC) in May 2019, when an appellant named Vikas Narayan, an ex-employee of TMIBASL filed an appeal, seeking clarification on the validity of Samant's educational degree.

Narayan approached the CIC after struggling to get transparent information through a question filed under the Right to Information (RTI) Act with the IRDAI.

The authority initially refused to provide information stating that it was personal and had no public interest implications. Documents with the authors show that the CIC investigated the issue and confirmed that Samant’s degree was invalidated by Chaudhary Charan Singh University.

Instead of reinstating Roy, TMIBASL and Samant filed a Rs-100 crore defamation suit against him in the Bombay High Court.

Roy’s legal battles intensified.

His bail cancellation hearings were repeatedly adjourned. New lawsuits were filed against him, including one in which Samant claimed that he had physically assaulted him—the complaint in this case was made more than seven years after Roy’s services were terminated by TMIBASL.

In his email messages to Mistry and Tata, Roy claimed these allegations were “baseless and retaliatory in nature”.

Samant filed a new defamation suit against Roy in Roorkee, Uttarakhand. On 15 May, the Supreme Court admitted an appeal by Roy’s lawyer requesting the transfer of the case from Roorkee to Kolkata, where Roy is based and where he operated out of while he was employed by TMIBASL.

We have learnt that Roy and his wife flooded the late Ratan Tata, his successor, Tata Sons chairman Natarajan Chandrasekaran, and others with email messages almost daily, detailing their financial struggles and the emotional toll that the lawsuits had taken on his family.

Roy’s appeals for withdrawal of the cases against him by TMIBASL and Samant have been ignored. He remains entangled in legal battles, still seeking justice. For a living he does freelance writing and translation.

‘National Security:’ A Law Is Killed

The Whistle Blowers Protection Act of 2011, was enacted to allow the reporting of corruption, misuse of power, or criminal offences committed by public servants while ensuring that they were protected and not victimised.

Introduced as a bill in the Lok Sabha on 26 August 2010, it was passed by the lower house of Parliament four months later on 27 December 2011, and by the upper house, the Rajya Sabha on 21 February 2014. The act received the assent of the President of India on 9 May 2014, and was notified three days later.

The act allows any individual or entity, including public servants and non-governmental organisations, to make a “public interest disclosure” related to acts of corruption or misuse of power by public servants to a competent authority, such as the Central Vigilance Commission or state vigilance commissions.

The act aimed at not just protecting the identities of whistleblowers but also shielding them from victimisation. It prescribed penalties for individuals who knowingly make false or frivolous complaints.

Despite its enactment, the act has not been operationalised. The rules needed to actually enforce the law and make it work haven’t been put in place.

In December 2014, the government indicated the need for amendments to safeguard against disclosures affecting the country’s sovereignty and integrity.

To address these concerns, the Whistle Blowers Protection (Amendment) Bill, 2015, was introduced and passed by the Lok Sabha on 13 May 2015.

The Law That Can’t Be Used

The new bill prohibited disclosures related to 10 types of information, including information related to sovereignty, security and “economic interests” of the State. The bill lapsed with the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha in May 2019 and has not been reintroduced since.

This means the Whistle Blowers Protection Act, 2014, is not in force.

The government has stated that amendments to the act were not part of the current legislative agenda. In December, 2014, the union minister of state for personnel, Jitendra Singh, noted that the act in its current form required amendments “aimed at safeguarding against disclosures affecting sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State”.

The consequences of the delay in operationalising the act have been flagged by activists who, in 2019, highlighted the fact that many faced threats to their lives or were killed while exposing corruption.

Activists have emphasised (here and here) the urgent need for legal protection for whistleblowers and urged the government to enact the law without further delay, arguing that pending amendments should not hinder its enforcement.

“The Whistle Blowers Protection Act was enacted after a prolonged campaign and struggle by civil society activists,” said Anjali Bharadwaj, co-convenor of the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information. “The demand for such a law gained momentum in the Lok Sabha following the murder of RTI activist Satyendra Dubey.”

The Story Of Satyendra Dubey

Dubey, an engineer working with the National Highways Authority of India, was murdered in Gaya, Bihar, on 27 November 2003, his 30th birthday. More than six years later, the high court of Bihar in Patna, convicted and incarcerated three persons on the basis of an investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

Questions remain as to whether Dubey was killed after he resisted attempts at robbery. Several witnesses during the trial died or disappeared, so many alleged that the killers were mercenaries acting at the behest of corrupt contractors against whom Dubey had blown the whistle.

Bhardwaj recalled that the 2014 Act was passed in Parliament with support from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was then in the opposition.

“There was hope that once the BJP came to power, the Act would be operationalised,” said Bhardwaj. “However, a decade has passed, and the government appears to lack the political will to implement or amend the legislation—amendments they themselves deemed necessary on the grounds of national security concerns arising from the Act.”

Bhardwaj’s associate, Amrita Johri, coordinator of Satark Nagrik Sangathan (Vigilant Citizens’ Organisation), an advocacy group, said a law “is crucial for the 1.45 billion people in India who are covered under the RTI framework.”

“The scope of the 2014 Act is limited to the public sector. It excludes the private and corporate sectors, permitting complaints against private sector officials only when there is evidence of bribery or another criminal offence involving a public servant,” said Johri.

‘Delay Is Denial’

Jagdeep S Chhokar, co-founder of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a think tank and advocacy group, explained why, in his opinion, the law remained unimplemented.

“Both the current government as well as the earlier Congress-led government have been reluctant to frame the rules that would make the government accountable, and that’s precisely what they wish to avoid,” said Chhokar. “Consequently, despite being passed by Parliament, the law lacks a formal structure and remains non-operational.”

A former civil servant and professor, Chhokar pointed towards the broader pattern: “A transparency law like the RTI (right-to-information) Act is passed under pressure from the public and civil society. But then this law is systematically weakened by not appointing information commissioners, downgrading their status, and by creating procedural hurdles.”

“No government wants to publicly oppose whistleblower protection…,” said Chokkar. “However, as Cyril Northcote Parkinson (a British historian and author of 60 books) aptly said, 'Delay is the deadliest form of denial.' That’s the tactic being used—indefinite delays that exhaust public interest and momentum… a lack of political will."

He said that the whistleblowers’ protection law and the Official Secrets Act (OSA), 1923, were fundamentally contradictory.

“The government relies on the Official Secrets Act to keep information confidential because 'information is power,’” said Chhokkar. “Whistleblowing, by definition, involves revealing information that those in power prefer to keep hidden. The OSA is a colonial relic with no place in a democratic society…”

Chhokar said that in private companies, shareholders were the actual owners and are entitled to transparent disclosures—including through filings with the Registrar of Companies.

“In practice, however, illegitimate or illegal actions often occur under the guise of serving the company’s interest,” said Chhokar. “When an employee with a conscience attempts to expose such wrongdoing, they are typically ostracised or targeted by those implicated.”

Meanwhile, cases of retaliation against whistleblowers keep emerging (here, here, here and here).

Yet, there is no proposal to provide statutory protection to whistleblowers in non-government organisations, notably private corporate entities.

Can Fin Homes Vs Whistleblower K

At Can Fin Homes, a government of India-controlled housing finance company affiliated to the public sector Canara Bank, a whistleblower, who we’re calling K, claimed that he had uncovered malpractices in recruitment allegedly orchestrated by a senior general manager. We are withholding this person’s name because the allegations against him are yet to be proved in a court of law.

In April 2024, K—then called chief manager, human resources (HR)---was in line to head the HR department in his company a year later.

That did not happen.

The following month (May 2024), K told us that he came across documents that had been manipulated. He alleged that his subordinate officers were being “coerced” to favour certain candidates who had applied for jobs in the company.

On 29 May 2024, K first complained to the HR head of Can Fin Homes. No action was taken, he claimed. He made more complaints internally.

In July, K was promoted to the rank of assistant general manager (AGM), HR. He remained perturbed, he said, that complaints about corruption in recruitment were being ignored.

On 15 May 2025, we emailed a questionnaire to the company’s official spokesperson. On 23 May, an unnamed spokesperson denied K’s allegations.

The spokesperson’s response explained how recruitments by Can Fin Homes followed what the company called standard operating procedures and guidelines. “No loopholes were found in the existing recruitment process (that) is transparent and fair,” said the spokesperson, dismissing K’s allegations as “not substantiated” and “totally baseless”.

‘Retaliatory Action’

On 23 August 2024 and the following day, K reported his findings to the company’s managing director (MD) Suresh Srinivasan Iyer. K claimed he made his complaints in the presence of other officers in the company’s HR department, including Aarthi Shetty, manager, and Shyaam Sunder, deputy manager.

Two days later, on 26 October, at 2.21 pm, K sent an email to the MD and the deputy MD of Can Fin Homes Vikram Saha. Four hours later came “retaliatory action,” or so K claimed.

The senior general manager who K accused of malpractices handed over a transfer order to him at 6.30 pm in the presence of Saha. K was asked to move from Bengaluru in Karnataka to Hyderabad in Telangana.

On 30 October, K, now in Hyderabad, escalated his complaint to the chairman of the company’s audit committee, Arvind Narayan Yennemadi. His complaint (a copy of which is with us) highlighted systemic failures in recruitment.

On 7 January 2025, NDTV Profit, a website, reported that K’s complaints were authentic. Other stories in Hindi and English followed. A noted Business Standard columnist also wrote about K’s case.

Set up in 1987, Can Fin Homes is controlled by Canara Bank, which holds a 30% stake in the company. The remaining 70% shares are held by domestic and foreign investors, and the general public.

The board of directors of the housing finance company is dominated by the top officials of its parent, including Canara Bank’s MD, executive director, general manager and deputy general manager. The bank’s MD holds the post of chairman of Can Fin Homes.

The ownership character of Canara Bank and its housing finance arm makes K’s claims of corruption in recruitment a matter of public interest. He told us that regulatory agencies, including the Reserve Bank of India, the National Housing Bank, the union ministry of finance, the ministry of corporate affairs, and the Central Vigilance Commission, were aware of his allegations.

“All I want is a high-level forensic audit to be conducted by an independent third-party agency,” said K. “I have all the documentary evidence to support my claims and allegations. I also have statements of witnesses from the HR department about how they were intimidated.”

‘Totally Baseless Allegations’: Company

The Can Fin Homes spokesperson argued that the K was given more than one opportunity to “submit concrete evidence in the matter, which he could not do…”

The spokesperson said there was “no question” of the company resisting a forensic audit of its hiring process, but since K’s allegations were unfounded, such an audit was not warranted.

The spokesperson further alleged that K’s claims were apparently “made to obstruct his transfer which appears to be his grudge”.

K said he stood by his allegations.

A writ petition relating to allegations of wrongful termination of employment was filed in the High Court of Chhattisgarh at Bilaspur by Dhananjay Kumar, branch manager of the Bhilai branch of Can Fin Homes. On 9 January 2025, the court granted a temporary injunction on K’s termination of service and on 23 April, asked him to move the civil court.

The Can Fin Homes spokesperson said the case had been decided “in favour of the company” and the letter terminating Kumar’s services was “upheld” by the court.

On 23 May, the day we received a response to our questionnaire, the company’s deputy general manager, on “orders of the MD and CEO,” served a show-cause notice on whistleblower K, threatening disciplinary action against him for a variety of reasons.

Those reasons include making allegations of recruitment irregularities, “instigating” his colleagues to oppose his transfer, tarnishing the image and reputation of the company, non-performance and failure to achieve business targets. He was to reply to the notice within five days.

In his reply of 28 May, K denied the allegations in the show-cause notice and reiterated his claims.

We are not disclosing the names of several individuals in the show- cause notice served on K and his response to it.

On 2 June, 2025, K was suspended from his post at Can Fins Homes.

Fraud in Tata Value Homes

In February-March 2015, Nitya Nand Sinha, a civil engineer working on a housing project in Bahadurgarh in Haryana’s Jhajjar district, promoted by Tata Value Homes, a subsidiary entity of Tata Housing Development Company (THDC) Limited, discovered discrepancies in statements on apartment areas that had been made to potential buyers of flats in the residential complex.

Sinha said he received two versions of “final sale area documents”—one with “actual” measurements and another where figures had allegedly been inflated. The second set of numbers had been put on the company’s website and in promotional material meant to attract homebuyers.

Concerned that potential buyers of apartments would find they were being deceived, Sinha first raised the issue of discrepancies in the numbers within the organisation. No corrective action followed. By June 2015, the Tata Value Homes fired Sinha, who continued questioning the “misleading” sales tactics.

Sinha launched a so-called “public awareness campaign” through email messages and social media posts. He reached out to government agencies, regulatory authorities, and senior executives of the Tata group of companies.

In response, Tata Value Homes filed two defamation suits against him: one in a civil court in Gurugram, Haryana, and another in a civil court in Mumbai, securing interim injunctions from both courts barring Sinha from making further public allegations.

Despite these legal constraints, Sinha’s campaign gathered momentum, prompting the Haryana Town and Country Planning Department to open an inquiry into the way the housing project was approved and whether THDC had complied with regulations.

It appeared that the company did not cooperate wholeheartedly with the investigation, thereby causing delays.

Documents available with the authors from various government sources indicate that in early 2024, Sinha sought access to official records from the senior town planner (STP), Rohtak, through a request made under the Right to Information (RTI) Act. He called for a copy of the “action taken report” on his complaint against the Tata Value Homes project alleging “mass cheating” of apartment buyers.

A Pointless Inquiry Over 2 Years

The senior town planner claimed that Sinha’s email had not been received and refused to provide the information he had sought. The RTI application was prompted by a letter issued on 25 September 2023, by the district town planner (DTP), Jhajjar, which detailed the findings of the inquiry into the Tata Value Homes project.

Sinha contested these findings, arguing that they failed to address the key discrepancies he had found. He objected to the DTP’s conclusions through an email dated 29 December 2023, sent to both STP Rohtak and DTP Jhajjar.

After the senior town planner did not respond, Sinha took the matter up to Haryana’s chief town planner, also the first appellate authority under the RTI Act. Dissatisfied, Sinha filed a second appeal with the State Information Commission (SIC), Haryana.

Following the SIC’s intervention, the STP Rohtak issued a letter on 18 January 2023. It appeared that instead of providing the information Sinha sought, the letter revealed that the inquiry had been closed or archived without informing Sinha or hearing him.

The STP had evidently misled Sinha by citing a 23-month-old memorandum, dated 18 January 2023, which bore no relevance to the status of the inquiry in question. We called the STP, Jhajjar, on his landline but could not reach him. We sent a questionnaire to the STP's official email address and if he replies we will update this story.

Sinha’s correspondence (seen by these writers) raised a critical question: Why did the DTP, Jhajjar, conduct an inquiry over almost two years, between 5 January 2021 and 20 December 2022, if no action was to be taken on the basis of the allegations levelled?

The long delays and the lack of response from the Haryana government’s regulatory authorities suggest how things work—or do not—a government source told us.

Against this backdrop, the Tata group’s housing arm went through a major internal shake-up. The MD and CEO of Tata Value Homes resigned. A restructuring of the group’s real estate and infrastructure businesses followed.

These developments sparked speculation about these changes being linked to Sinha’s allegations.

On 15 May, we emailed a questionnaire to Sanjay Dutt, MD and CEO, Tata Realty & Infrastructure Limited and THDC. There was no response. We will update this story if there is.

Meanwhile, Sinha had acquired a law degree and was personally fighting his legal battles.

A Pyrrhic Victory

On 11 April 2025, the civil judge (junior division), Gurugram, delivered his final judgment in the defamation suit against Sinha.

The court held that while he had a legitimate right to report grievances to public authorities and law enforcement agencies, his use of terms such as “goons” and “habitual offender” in email messages to media outlets and the Tata group’s business partners—specifically the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank group and the biggest lender of its kind to the private sector—was prime facie defamatory.

The court found that although these statements by Sinha could have harmed the Tata group company’s reputation, no actual financial damages had been proven.

The court dismissed Sinha’s demand for monetary compensation, stating that the allegedly defamatory content was unlikely to have had a material impact on the operations of the Tata Value Homes project.

The court granted a permanent injunction restraining Sinha from further disseminating defamatory content about the company and its employees. At the same time, the judgment reaffirmed his right to pursue whistleblower disclosures through “proper channels.”

We have learnt that Sinha has appealed the judgement.

When contacted, Sinha—the civil engineer who turned whistleblower, then turned a lawyer—did not want to comment on the defamation cases that he has fought against one of India’s best-known and most-reputed corporate conglomerates.

After a legal battle spanning more than a decade, Sinha’s victory appears to have been pyrrhic.

(Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Ayush Joshi are independent journalists.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.