Aligarh and Agra and Mumbai: In March 2017, life was going along rather well for S (name changed on request), then 48, a butcher from the neighbourhood of Dodhpur in the western Uttar Pradesh (UP) district of Aligarh. The son of a butcher himself, S, a stout, fearless man, employed two, and earned enough to sustain a household of six children and 2 elderly parents.

S’s life, like thousands of others in the meat and leather trade, mostly Muslim, first began to change in 2015 after a National Green Tribunal (NGT) order, two years before the government of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) chief minister Yogi Adityanath, a Hindu priest who follows a hardline Hindu-first policy, took office as chief minister of India’s most populous state, after which there was a steady acceleration in restrictions.

We counted at least 10 requirements that the government forced on the meat trade, from infrastructure—freezers and geysers to curtains to white-washing premises—to new paperwork from various departments, from the police to food and drug officials.

As the new government orders forced S to invest in licences and infrastructure, his economic decline began.

In 2017, he had to fire both his employees, who cut meat and managed the shop, allowing him time to try and grow the business. One now works in a fruit shop, and the other, about 65 years old, was too old to move on, and ended by begging for a living on the streets.

Restrictions on the sale and processing of meat and its main byproduct, leather, has meant a loss of livelihoods and a chance at upward mobility for thousands of small-time butchers, entrepreneurs, traders, meat-sellers and tanners across UP and Maharashtra, according to our study, conducted over six months across five cities of India’s leading meat-exporting states in 2021 and 2022.

In the first of a two-part series, we draw from fieldwork in Aligarh, Kanpur, Lucknow and Unnao in UP and Mumbai in Maharashtra to explain how majoritarian policies, discriminatory towards those in the meat industry have affected lives and livelihoods in UP and Maharashtra. The second part investigates a similar effect and decline in the related leather industry in UP.

Of UP’s over 200 million people, 19.3% or about 38 million are Muslim. About 11.5% or 12.9 million of Maharashtra’s 112 million people are Muslim.

We found that the new guidelines were too formidable for any small-scale butcher and meat seller. They make the trade of meat undignified, degrade it in the public eye and make lower-caste Muslims prone to harassment from cow vigilante groups, police and bureaucrats.

The only legal way for a butcher to slaughter an animal is by paying new fees and bribes, even as their earnings have dropped because they must now hand over the skin and guts to private slaughterhouses, who have emerged as new middlemen in the trade. An anecdotal estimate provided by some of the butchers we interviewed, indicated fees and bribes have risen 10-fold, from Rs 1,000 to Rs 10,000.

S’s business survives, but only just. “How could I buy a geyser and a freezer and still keep any staff?” he said. “Now I must cut the meat here myself.” His uncle and nephew, who once helped him in trying to expand the business, now assist him merely in keeping it running.

“Earlier, I could visit the shop once in the morning and then either do other work, or work to expand this business (such as overseeing meat supplies),” said S, who spends 12 hours at his stop, up from three to four previously. “Now, I cannot leave.”

Adityanath Seizes An Opportunity

The first setback to businesses like S’s came in May 2015, when the NGT, while hearing a petition to shut down slaughter-houses polluting ground and river water, ordered government and privately owned slaughterhouses shut in UP, India’s largest producer of meat with a tenth of the country’s cattle and 25% of buffaloes, according to the 2019 20th Livestock Census.

From March 2017, Adityanath’s government closed 44 slaughterhouses mentioned by the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board (UPPCB) in a list of “seriously polluting industries which have not installed anti-pollution devices”. Thirty-nine of these 44 slaughterhouses were run by local municipal authorities and provided an affordable and safe opportunity for the local, informal butchers (largely lower-caste Muslims) to slaughter animals.

The government did not upgrade most slaughterhouses, except for one run by the Agra Municipal Corporation. Over the next few months, Adityanath’s government issued guidelines for the trade of meat and ordered the shut down of slaughterhouses and meat-sellers operating without a licence.

Adityanath has repeatedly called for an end to the “illegal” slaughter of cows and restrictions to the meat trade. “We will ensure that all illegal slaughterhouses are shut down,” he said a month before he became chief minister.

Adityanath has frequently repeated the need for these restrictions (here, here and here), arguing that the closure of allegedly illegal slaughterhouses was because the “NGT has been asking for dealing with unhygienic conditions and filth in the state”. He has also advocated for bans on the sale of meat and liquor in Mathura and Ayodhya and on the route of the Kanwar yatra, a Hindu pilgrimage route, citing “public sentiments”.

The UP government also charged alleged beef traffickers with the draconian National Security Act (NSA), 1980, in which an individual can be held in detention—without a chargesheet—for up to a year. In 2020 alone, till mid-August, 55% or 76 of 139 NSA cases were related to cow slaughter, the the Indian Express reported in September 2020; in broadly the same period, the police arrested more than 4,000 on accusations of slaughtering and/or smuggling beef under the UP Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act 1955.

In June 2020, the state government promulgated an ordinance designed to further strengthen that law: from the earlier punishment of imprisonment up to seven years or a fine up to Rs 10,000, or both, slaughtering and/or smuggling of cows and their progeny can now lead to an imprisonment up to 10 years (and not less than three), and fines up to Rs 500,000.

Although Maharashtra has laws broadly similar to UP’s, these were poorly enforced by the coalition government of the Maha Vikas Aghadi alliance led by the Shiv Sena of former chief minister Uddhav Thackeray, when we conducted this study between 2019 and 2022.

But various data, such as the 2014 Mahmoodur Rahman Committee report, revealed that Maharashtra’s 10.2 million Muslims (in 2014) suffered poverty, prejudice and discrimination in most aspects of their lives, lagging behind the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, in what is India’s richest state economy.

The most recent evidence that the UP government's attitude was aligned with Adityanath’s ideology came when meat shops along the route of the Kanwar yatra were ordered shut for 59 days or nearly two months starting July 2023. In the town of Muzaffarnagar, 114 Muslim shop-owners and butchers called in by the police for talks over a Kanwar shutdown were detained in Muzaffarnagar on charges of “disturbing the peace”.

Official discrimination segues into an increasingly evident strategy of Hindu extremist boycott calls and attacks on the livelihoods of Muslim businesses and workers. UP has also seen a clear rise in cow-related vigilantism.

UP is India’s largest buffalo meat-exporting region with exports of over Rs 10,000 crore a year and a leather industry (dependent on animal skins) with an annual turnover of Rs 25,000 crore. For years, much of the industry was only partly regulated, as is the case with many informal businesses nationwide. They had never encountered the infrastructure requirements and flood of paperwork that the UP government piled on them

How The Meat Trade Was Stifled

In March 2017, three days after taking office, Adityanath’s government rolled out a series of guidelines for the meat business, largely made of informal or small-scale businesses.

These were the new guidelines:

– A meat shop could not be located within 50 m of a religious place and 100 m from the main gate of a religious place

– Slaughtering meat inside the shop was prohibited

– Sale of meat was banned in areas where vegetables were sold

– Meat shops had to use curtains and/or tinted glass to ensure meat was not visible from the street

– Health certificates from government doctors for all those working in the shop

– No objection certificates (NOCs) from the police and the municipal corporation to run a meat shop in urban areas; from the police and gram panchayat (village council) in rural areas

– NOCs from the Food Safety and Drug Administration

– White-washing of the shop every six months

– Installation of insulated freezers and geysers in the shop

– Transport passes, gate passes and clearances to transport animals and slaughter them at ‘legal’ slaughter houses

– Receipts that prove that the animal was slaughtered in the slaughterhouse

How Small-Scale Butchers Were Hit

Small, privately owned businesses run by lower caste Muslims faced the brunt of the new guidelines, especially since government-run slaughterhouses in UP were not reopened after being shut for pollution violations.

The bulk of animal slaughter nationwide is done by small-scale butchers or in homes. Government-sanctioned slaughterhouses are few and difficult to access, especially for those outside the large cities.

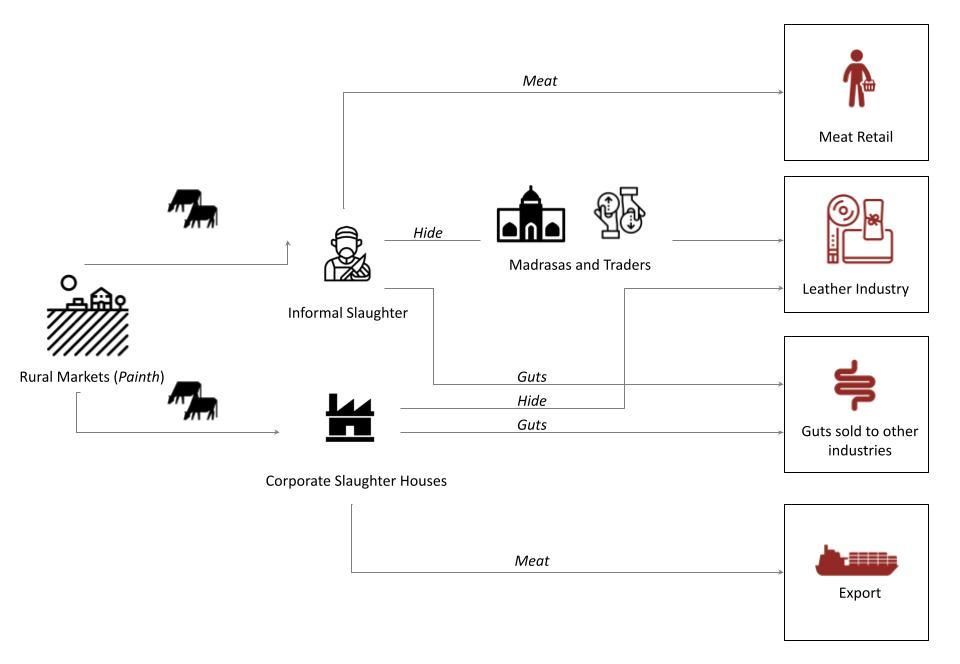

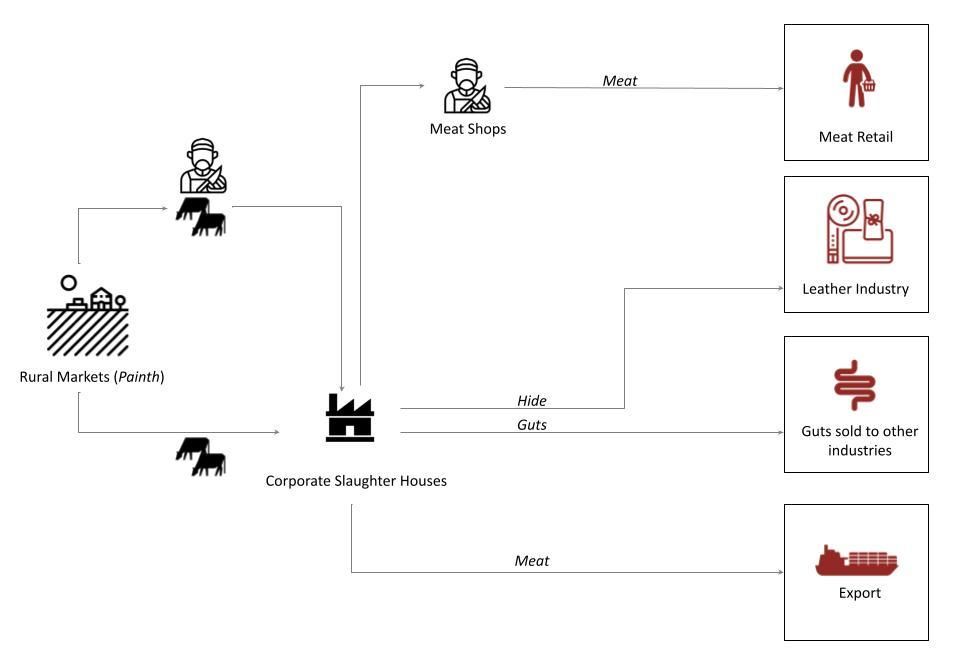

Interviews we conducted revealed how the meat trade was structured before the new restrictions.

A. For butchers:

B. For private slaughterhouses

The new guidelines made slaughter anywhere but in slaughterhouses illegal. With municipal slaughterhouses not reopening, the trade now unfolds thus:

From Rs 1,000 To Rs 200-300: Earning Drop Per Goat

Our study showed that the new guidelines made private slaughterhouses mandatory, new intermediates to the meat trade.

“I used to make good money by slaughtering my animals at the government slaughterhouse,” said S, the butcher quoted at the start of this story. “The skin and the guts also gave me some money on the side and I could run my shop with an employee. Now, I have to give a cut to the private slaughterhouse, and they keep the skin and the guts. Prices went up at first, and sales went down. So, we had to bring prices down.”

Where S once earned a profit of Rs 1,000 per goat before the new guidelines and the emergence of the private slaughterhouse as intermediary, he now earns Rs 200 to 300. He noted that he and most other butchers in Aligarh are now dependent on slaughterhouses run by private companies like the Allanas and Al-Tabarak, where the company takes important parts like the head of the goat, the hides, hooves etc and leaves butchers like him with the liver, legs and meat.

In S’s city, Aligarh, where once there were at least 51 informal slaughterhouses, there are now only nine, approved by the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA). All these slaughterhouses earn money through slaughter fees and sale of skin and guts, eliminating the arhatiya middlemen and madrasas, which meant employment to hundreds in just Aligarh.

Harassment, Stigma & The End Of Small Businesses

The new guidelines for the meat trade also stigmatised those who made a living from it.

Aside from the inability of local shops to keep up with the strict guidelines, there is an increased stigma that these guidelines have generated. explained: “It seems like we are doing some dirty work,” said M (name changed) who lives in Aligarh’s Tantanpara locality. “The threat is constant. I have to keep passes, permissions and NOCs. Even if the slightest thing is off, they can beat me and put me in jail.”

M faces a case of illegal cow-slaughter, which he claims was the result of a personal feud. “I had simply gone to intervene in the abusive marriage of a friend’s daughter from our neighbourhood,” he said, his weariness apparent.

“The man used to beat her, I intervened and he did not like it,” said M. “They knew I was a butcher, so they told the police that I slaughtered (animals) illegally and got me booked.”

We found the rise in paperwork and stigma made UP’s butchers increasingly prone to such harassment and violence. In the Aligarh neighbourhood of Jeevangarh, a butcher, speaking on condition of anonymity, explained how he has to pay greater bribes to the local police station because he could not afford to line his shop floor with vitrified tiles.

The documentation requirements to run a retail shop for meat also sucks capital away from small businesses. Before the new guidelines, a butcher could operate a shop with a municipal corporation sanitary pass. This, as our interviewees explained, cost Rs 1,000 each year and was easily renewable.

The new guidelines, however, as we said before, mandate both a Food Safety and Drugs Administration licence, permissions from the local police and medical certificates for the employees working at the shop.

R, another Aligarh butcher, explained how all he needed earlier was a sanitation licence to sell meat. “It was cheap and much easier,” he said. “Now, I have to spend nearly Rs 10,000 in fees and bribes to get all the documents. Since I cannot keep up with the requirement for the freezer etc, I [also] have to bribe the local policeman and the sanitary inspector to get by.”

Cost Of Majoritarianism In Maharashtra

Soon after the swearing-in of the BJP-Shiv Sena alliance government in 2014, the President of India granted assent to amendments to the Maharashtra Animal Preservation Act 1976, proposed by the alliance government in 1995.

“[T]hese amendments sought the complete shutdown of the cattle meat trade even as Muslims in the trade were urged to close their businesses and shift to other menial occupations such as weaving,” a civil society member privy to a meeting of representatives of the state’s Muslim community with bureaucrats in 1996, told Article 14 on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue.

Nineteen years after the passage of these amendments, and the swearing-in of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister in 2014, presidential assent paved the way for the notification of these amendments in 2015, which meant they were now law.

These amendments included a complete ban on the slaughter of bulls and bullocks in Maharashtra, in addition to the pre-existing prohibition on the slaughter of cows. Only female buffaloes and buffalo calves could be slaughtered, but only after permission from the animal husbandry department.

The amendments also banned the transport, export, sale and purchase of cows, bulls and bullocks with the “knowledge it will, or is likely to be” or “having reason to believe” it will be slaughtered. The government ignored internal discontent against the ban within the ruling alliance, especially from those representing rural constituents.

The Maharashtra animal husbandry department sought to implement the 2015 beef ban through the recruitment of honorary animal welfare officers, many of whom were former cow vigilantes (gau rakshaks). However, these controversial recruitments were not approved by a monitoring committee appointed by the Bombay High Court.

Meat traders we spoke to in Mumbai attributed the lack of vigilantism and arbitrary police actions to the change of political climate after the Maha Vikas Aghadi government came to power in Maharashtra in November 2019.

As per a database last updated in August 2017, two out of 75 cow-related vigilante attacks from 2012 to 2017, were in Maharashtra. However, since the arrival of the BJP-Shiv Sena government in June 2022, the state has witnessed at least three cow-vigilante related deaths, and heated politics over the cattle trade.

Our interviews in Mumbai and its neighbouring suburbs, revealed that meat sellers and traders in the suburbs of Deonar, Bandra and Malad viewed the restrictions on slaughter, sale and consumption of meat purely as attacks on Muslims.

A prominent local trader who possessed both licences and enjoyed relative economic security told Article 14 that he continued in the trade, not by choice but because his occupation was an “unavoidable part” of what he called his “self-identity”. Moreover, there were few other options.

“What else can I do?” he exclaimed, when asked if he would stay in the meat trade, if the situation grew worse.

While the new generation of butchers and meat sellers in Maharashtra has been trying to seek alternative employment, opportunities are scarce. An interviewee, Arif Qureshi, said that despite educating his sons in engineering colleges, they had not found jobs.

A, a beef shop owner in Mahim, Mumbai, speaking on condition of anonymity, said his livelihood had been “destroyed”, and he had to bribe police to survive. He was hesitant to share details but said that where he once hired at least five to six employees, he now does everything himself.

These incidents and the everyday harassment of cattle traders had created an environment of fear and precarity. An affluent meat trader from Mumbai’s Muslim community said that he was “forced to end” his lucrative supply contract with a five-star hotel in Goa, after the delivery vehicle was stopped by the police once in 2017.

“I felt so humiliated and embarrassed, because I was asked to prove if the meat was beef or not”, he said.

The Bottlenecks At India’s Largest Abattoir

Apart from cattle-slaughter laws, butchers and traders told us how they had to navigate a raft of other laws increasingly used against them, such as the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, and those related to vehicular pollution. As in UP, slaughter itself had become far more difficult.

Consider the case of the Deonar abattoir on Mumbai’s eastern edge, one of India’s largest abattoirs and the only one legally permitted to butcher goat and sheep after a 2019 Bombay High Court order disallowing slaughter in residences, private spaces or shops.

The first set of logistical hurdles for butchers begins at the Deonar abattoir, with the number of cattle that can be slaughtered every day and when: 300 horned cattle in an eight-hour shift, a number wholly inadequate to meet demand, which is met indirectly by a booming black market.

The abattoir was shut during the Covid-19 pandemic and only partially reopened, causing losses to traders. Unlike in normal times, the abattoir was only open for eight hours between 11 am and 7 pm, where once it was open 24 hours.

Most traders are done with daily meat sales only by 2 pm, leaving them very little time to conduct business at Deonar. “Allowing slaughtering from 11 am to 7 pm does not make sense,” Shahnawaz Thanawala, president of the Bombay Mutton Dealers Association, was quoted as saying. “It should instead be allowed from midnight until 5 am. This would leave enough room for them to reach the market in time”.

When we were conducting our study, the Deonar abattoir was only open to local traders in Mumbai, whose vehicles had to display local registration, making an estimated 80% of local traders ineligible.

Muniappa, a worker at the Deonar slaughterhouse, paid per animal slaughtered, estimated his monthly income was down by Rs 20,000 since the 2015 ban on the slaughter of bulls. Cattle traders estimated that 2,000 lost jobs in Deonar alone.

Prior to the ban on the slaughter of bulls, 1,500 cattle were slaughtered at Deonar every day. This fell by about a tenth to between 150 to 200 cattle after the ban and the pandemic. Since July 2020, when the government allowed an 8-hour-long at the Deonar abattoir, numbers of cattle slaughtered have risen to between 300 and 400, not yet a third of its peak.

E, a migrant from UP and a meat trader, said the trade at Deonar used to employ over 2,200 workers, primarily from marginalised Muslim castes. This was his ancestral occupation since 1965, he said, noting an escalating crackdown on their professional freedom since the 1990s, after BJP leader L K Advani’s rath yatra in 1990, a nationwide procession regarded as a prime catalyst for a rise in Hindu majoritarianism, culminating in the destruction of the Babri mosque in 1992.

“They (the police) used to ask us to swear an oath that the animal we were transporting was not for slaughter”, said E, who added that the severity of restriction fell during Congress rule in New Delhi between 2004 and 2014.

Many traders were “millionaires at one time”, said E, but now struggled to repay debt as little as Rs 80,000.

H, a driver transporting cattle to Deonar, reported a loss of over Rs 40,000 in monthly income over 6 years and a rise in risks on the road whenever a government led by the BJP ran Maharashtra.

Yet, The State Pushes Beef Exports

Interviews with retail beef sellers in Maharashtra revealed discontent at the sustained export of meat to foreign countries. They said while local Muslim-run businesses struggled to sell beef, prominent export companies with Hindu partners have secured supply contracts that are larger than before.

Cattle-meat suppliers also cited APEDA regulations that require meat suppliers to be registered, preventing large export companies from sourcing meat from unlicensed local suppliers.

Virtually everyone we spoke to claimed that Muslims in Maharashtra sell and eat less meat than before. One interviewee, A, claimed that their sales had come down from 300 kilos a day to 70 kilos a day; another interviewee, F, claimed that it had come down to from 100 kilos to now 50 kilos a day, or about 50% to 60% fall in his revenue. Paradoxically, reports indicate that slaughter of buffaloes had in fact risen since the ban.

The biggest abattoir of Deonar reported a steady growth in cattle slaughter (except 2020-2021, when many did not show up to work after the outbreak of Covid-19), 41% in 2019-2020 compared to 2016-2017. Figures collected by the animal husbandry department in 2018 for the previous years revealed that slaughter of buffalo touched an all-time-high in Maharashtra (at 961,516, up from 6,13,134 in 2014-2015 at the time the ban was enforced).

It appears clear that if local consumption and sale of buffalo meat hasn’t picked up, the larger quantities coming out of slaughterhouses are going to State-supported exports. As per data from APEDA, as of 2022-2023, India was the fourth largest exporter of beef (buffalo meat) in the world, and accounted for 43% of the world’s buffalo meat production.

Data from the ministry of commerce & industry during the past decade shows that buffalo exports, although they have declined for Maharashtra, still constitute the highest in the country after Uttar Pradesh.

In UP, export revenues have increased at a compound annual rate of 9.08% from the period between 2012 to 2022, despite the restrictions, as per data obtained from the Ministry of Commerce & Industry’s APEDA in 2021. In non-BJP states, such as Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal, the compound annual growth rate is 16% , 39.9% and a whopping 67.45% between 2012 and 2022, according to APEDA statistics.

This is the first of a two-part series. You can read the second part here.

(Sharik Laliwala is a researcher and doctoral student in political science at the University of California, Berkeley. Sabah Gurmat is an independent journalist and legal researcher based in New Delhi. Prannv Dhawan is a legal researcher based in New Delhi. The research was conducted in an independent personal capacity.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.