Bengaluru: Bound by gag orders, rushed by impossible deadlines, and pressured to give reports favourable to the project—scientists assessing the Rs 81,000-crore mega project in the Great Nicobar Island worked under a shadow of institutional coercion for assessments of the environmental impact of the project, raising serious questions about the integrity of environmental clearances granted for the project.

Located about 40 nautical miles (74 km) from the Strait of Malacca’s busy shipping route, the proposed infrastructure mega project in the Great Nicobar island includes a transshipment terminal, an international airport, power plants, a township and high-end tourism facilities, all set in lush rainforests, as Article 14 reported in September 2023. These forests are also home to two tribal communities, the Shompen and the Nicobarese.

The Great Nicobar project is currently in the final stages of statutory approvals.

Despite warnings (here, here and here) about irreversible biodiversity loss and threats to endangered species such as the Giant leatherback turtle, official assessments have downplayed the impact, declared that translocation of certain flora and fauna is possible, and that there would be minimal disruption, in what experts call a deeply flawed process.

The assessments on how the project will impact the region’s biodiversity were conducted by three organisations, the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON) and the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI). Both WII and ZSI are wildlife research organisations under the union environment ministry. SACON is WII’s South India centre.

Based on the assessments conducted by these organisations and on mitigation measures proposed by them that aim to ‘minimise’ biodiversity harm, the union government gave environmental clearances to the mega project to raze 130 sq km of rainforest—over a million trees—in the Great Nicobar Island,

The assessments, however, have serious shortcomings, according to multiple scientists and researchers who spoke both on and off the record. They also expressed concerns about the manner in which the assessments were conducted.

In September 2023, Article 14 reported that the union government ignored claims made by the Nicobarese that the forests chalked out for the project were their traditional lands and were being taken over despite their opposition.

In an interview in September 2024, Anstice Justin, a Nicobarese anthropologist and former deputy director of the Anthropological Survey of India, told Article 14 that the forests are sacred to the Shompen, an indigenous community that has inhabited the island for thousands of years, who communicate in a unique language that is yet to be deciphered.

“To them, nature is sacred and similar to temples, churches and mosques. Do we destroy our places of worship?” Justin said.

“When we have no respect for the beliefs of people, our approach to develop the area is very profane and unconsecrated.”

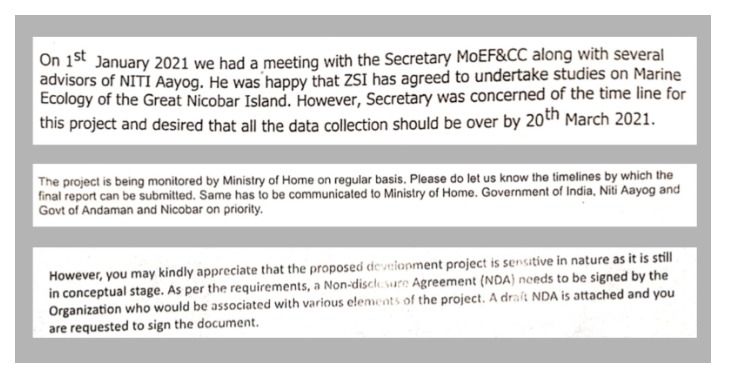

Responses to requests under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005 reveal that scientific institutions signed non-disclosure agreements for the assessments, amid close monitoring by the union ministry of home affairs and a push for expeditious completion of their assessments.

The RTI requests were filed by various activists. They show email correspondence between ZSI and AECOM, a private multinational consulting firm. In 2021, the NITI Aayog had hired AECOM to prepare a feasibility report for the mega project.

Article 14 sent questions to officials at AECOM and ZSI asking why non-disclosure agreements were signed, and whether the agreements prohibit the disclosure of biodiversity impacts assessed as part of the environmental clearance processes. We did not receive a response. If we do, we will update this story.

Other scientists and researchers across all three institutes (ZSI, WII and SACON) who worked on environmental and biodiversity assessments for the Great Nicobar project also signed non-disclosure agreements.

A Scientist Resigns

In April 2021, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation (ANIIDCO), the project proponent, tasked WII with conducting a study to assess the environmental sensitivity of the port project.

ANIIDCO also consulted with the environment appraisal committee (EAC) under the union environment ministry to ascertain the objectives of the study. The mandate of the EAC is to scrutinise development projects for environmental clearances.

The “rapid assessment” report by WII, titled ‘An assessment of the environmental sensitivity of sea turtle nesting beaches of the Great Nicobar Island’, conducted as part of the environment clearance process, was carried out over just six days in mid-April 2021.

Many turtle species, including the globally vulnerable giant leatherback, swim to the beaches of Great Nicobar each year to lay eggs. Peak nesting season is December to January—a period the rapid assessment did not cover. Galathea Bay, the site of the mega port, is the single largest nesting site of the giant leatherback turtle in Great Nicobar island.

Unsurprisingly, the assessment barely found any nests of the giant leatherback.

In addition, the WII study used drones to survey seagrass beds for the presence of dugongs, a marine mammal. Drones are limited by capacity to assess only shallow areas, and no dugongs were found.

Avadhoot Velankar, a former researcher at SACON, told Article 14 that scientists at government institutions were basically asked to provide reports favourable to the project.

“Senior scientists went along saying ‘since the environment ministry is asking, we will do it,’” said Velankar.

“If some of them were morally against it, they were arm-twisted by directives from the environment ministry and their jobs were on the line if they spoke out…”

Velankar said a faculty member left WII because of the pressures to clear the Great Nicobar project.

K Sivakumar, PhD, served as teaching faculty at WII and led their marine biodiversity research team. He also led the WII rapid assessment report as its principal investigator. He left WII in January 2022.

In a webinar in 2020, Sivakumar noted that the mega project was “not at all good to sustain the environment in [Great] Nicobar island”. He said that while it may be strategically important for the government, “the moment this [transshipment terminal] comes, we should forget about Great Nicobar”.

In the same webinar, he added that he had “begged” the NITI Aayog to take biodiversity impacts into account, but to no avail. This was in reference to a meeting held by the NITI Aayog as part of preliminary discussions about the mega project. “I couldn't convince [the NITI Aayog]. I am sorry for that. The government went ahead and invited tenders,” he said.

However, the WII’s rapid assessment said the administration must develop and implement a plan to facilitate “continuous nesting” of giant leatherbacks and other turtles in Galathea Bay, and to maintain connectivity between Galathea river and the bay. The current design of the mega project means this connectivity will be disturbed, as will nesting sites of the turtles.

This reporter has also learnt that at a recent job interview at SACON, candidates were asked about their position on the Great Nicobar mega project, indicating that dissenting views were not welcome.

Claims Of Relocating Birds, Crabs

In April 2021, the environment ministry tasked the ZSI with carrying out a detailed study on the ecological impacts of the project. The ZSI’s study, submitted in July 2021, recommended environmental clearance for the project citing the following, among other claims:

It said the environmental impact of the mega project was “presumed to be negligible”, and that as endemic birds “are highly mobile, translocation of the habitat may take place”.

Other endangered faunal species such as the Nicobar megapode and the coconut crab “can be relocated in safe and suitable place”, it said.

The project entails the diversion of 130 sq km of rainforest land for non-forest purposes, which this study termed as a “negligible” environmental impact.

Sivakumar told Article 14 that it was “next to impossible” to relocate Nicobar megapodes to other sites.

“Only those who do not know about the bird can say it can be relocated. Their breeding behaviour, mound nesting and site selection to attract partners is very sensitive,” he said.

“It’s not just a nest which you can relocate and incubate.” Sivakumar has studied Nicobar megapodes over many years.

The ZSI study suggested long-term monitoring of “displaced” wildlife such as saltwater crocodiles and the giant leatherback turtle, but without first referring to the displacement as a cost.

Contradictions & Other Failings

A researcher who formerly worked with ZSI in Port Blair said that suggestions of translocation and negligible impact were “in complete contradiction” with what the ZSI had said earlier in its research, book chapters, and PhD theses, in which they emphasised conservation and describe some of the species in the region as endangered and vulnerable. The researcher spoke on condition of anonymity because of fears of reprisal.

On the kind of assessment exercise ZSI undertook for green clearances for the mega project, the researcher said the institution was asked to conduct very short-term studies spanning about a week.

The researcher also said the composition of the research team was “compromised”.

“They took people who they knew would keep their mouths shut,” said the former ZSI researcher. “And the study was based on secondary data because there was no time for real ground work.”

While the ZSI study did not detail the adverse impacts the mega project could have on coral reefs, it made a passing reference to their translocation.

It stated that coral colonies impacted by the project would be translocated to suitable places, elaborating neither on the potential impact of such a translocation nor on the translocation plan itself. It also referred to the coral reefs around the island as “scattered reefs”, not major reefs.

Marine biologist Rohan Arthur said, “There is no way of independently verifying the claims since few of us have been able to survey the sites ourselves, so we just have to take ZSI’s statements for what they are.”

Arthur added that independent of whether there was a major reef in the area or not, the translocation plan was a “questionable exercise”.

‘A Slippery Slope’

Relocating an entire coral reef is very different from translocating coral plants.

A coral reef, an ecological entity, harbours rich biodiversity, supporting the creation of a heterogeneous habitat, providing ecosystem services for these. In many cases, corals are integral to other major ecological processes, such as the formation of an island. For example, Lakshadweep is a coral island.

Even if every coral plant from a reef was removed and replanted at a location more convenient to the project proponents, this would be a far cry from relocating the reef, Arthur explained. “Central to this is how we conceive of the fungibility of ecosystems, species and functions,” he said. “If we believe them to be infinitely replaceable, it takes us down a slippery slope.”

Nevertheless, the director of ZSI, Dhriti Banerjee, PhD, told the National Green Tribunal in April 2023 during a hearing of a challenge to environmental clearances accorded to the project that corals could be protected even with the development of the project, and that environmental impact on them could be sustainably managed.

The ZSI report also has a section titled ‘envisaged benefit of the project’, in which it describes the “strategic importance” and socio-economic benefits of the mega project, regardless of the fact that the mandate from the EAC, under the union environment ministry, was limited to ecological assessments and of the fact that the ZSI does not have the expertise to assess strategic or economic matters.

M D Madhusudan, a conservationist who was previously with the Mysore-based non-governmental organisation Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), said regulatory bodies, such as the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) and the environmental appraisal committee, are mandated to comprise members with expertise to evaluate environmental impacts, carry out site inspections, and scrutinise assessments.

“Their fundamental mandate is to safeguard environmental and conservation standards within the regulatory framework,” said Madhusudan, who earlier represented the NCF as a member of the NBWL.

Regardless of the quality of reports submitted by institutions such as the WII or ZSI, he said, the onus remains on the NBWL and EAC to conduct rigorous scrutiny and due diligence before endorsing their recommendations.

The EAC, however, accepted the assessment reports without any independent assessment of their conclusions and recommendations.

Deepak Apte, chairman of the EAC and a former director of the Bombay Natural History Society, did not respond to Article 14’s questions about concerns with the reports submitted by WII and ZSI, and about why the EAC did not conduct an independent assessment.

In a signed editorial in the July-September 2018 issue of the magazine Hornbill published by the Bombay Natural History Society, Apte wrote that the magnitude of infrastructural development envisaged by the mega project was “not just scary, but incomprehensible”. He wrote, “The islands are of great national strategic importance and thus the infrastructure development in this regard is understandable. However, if one browses through the recent documents of Niti Aayog ‘Incredible Islands of India (Holistic Development)’ one would be bewildered by the changes that are slated to take place in these extremely fragile ecosystems.”

We also sent questions to union environment minister Bhupender Yadav, his secretary Amar Singh and joint secretary Neelesh Kumar Shah about the manner in which impact assessments for the Great Nicobar mega project were conducted under coercion and secrecy. There was no response. We will update this story if there is.

Restricted Research

Various researchers and scientists, including those who worked with these institutions, said there were serious restrictions on any research on the Great Nicobar island by those not affiliated with WII and ZSI. These researchers and scientists were guarded and only agreed to speak off the record.

In one instance, in December 2023, the research advisory committee of the Andaman and Nicobar forest department asked a conservation and research organisation to limit its study of seagrass meadows in the Andaman and Nicobar group of islands to the Andaman group alone.

Those wishing to conduct research in the region have also been asked by the Andaman and Nicobar forest department to provide assurances, including in written letters that they would not travel to Great Nicobar in the course of their work elsewhere in the Andaman and Nicobar group of islands.

Standards for environmental assessments done before projects are given clearances have been poor for years, and institutions like the WII and ZSI lack structural independence, Madhusudan said. “Assessments for the Great Nicobar project are just the most recent example,” he said. “Reports have been egregiously wrong and there is no transparency or scope for public scrutiny.”

(Rishika Pardikar is a freelance environment reporter covering science, law and policy. She is based in Bengaluru.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.