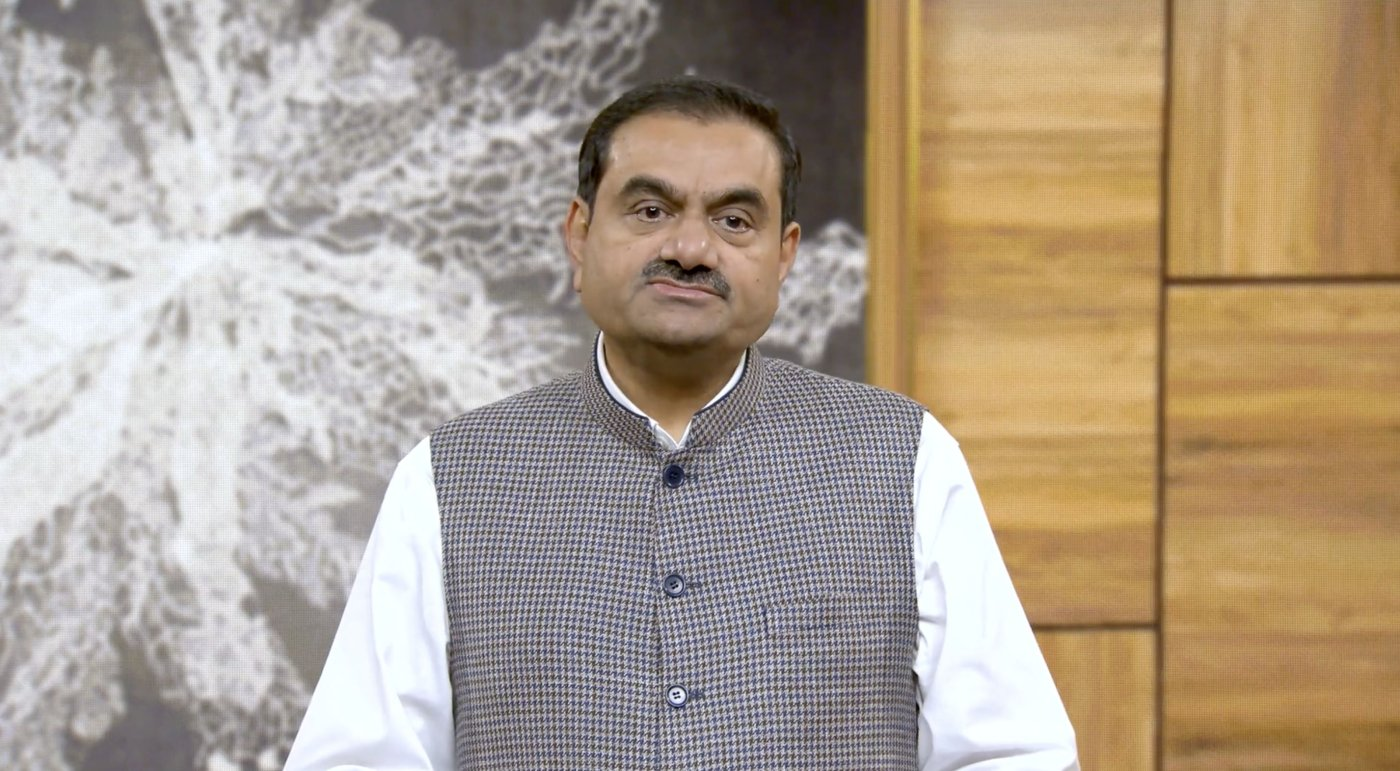

Bengaluru: For over 20 years, as Gautam Adani first grew in Gujarat and then spread his business empire across India—from a turnover of Rs 3,300 crore in 2000 to Rs 309,000 crore in 2024 —allegations of preferential treatment by governments in New Delhi and in the states accompanied his expansion.

The growth of his multibillion-dollar empire, now spread across six countries, was primarily built in India on three pillars: constant expansion into new industries, inorganic growth and debt. Each pillar has carried the taint of these allegations.

The group’s expansion was aided by bidding norms changed to favour the Adani group—as in the case of airports—to facilitate his entry. Similarly, the Dharavi Redevelopment Project to makeover to India’s largest slum in Mumbai was recast in 2020 such that the previous winner was not eligible any longer.

Its inorganic growth (acquisitions) was benefitted from a curious overlap where state agencies cracked down on firms Adani was eyeing—such as GVK’s Mumbai airport, although GVK group vice chairman Sanjay Reddy denied such pressure—or the ports of Gangavaram and Krishnapatnam, run by Andhra Pradesh businessman D V S Raju till 2021. In 2023, Raju too denied any coercion.

The Group’s debt-backed growth, sizably raised by pledging shares, was accompanied by allegations of share-price rigging—first reported by Indian newsrooms (here and here) and then by US company Hindenburg Research (here)—none were investigated.

There are other instances of preferential treatment. In 2018, Adani’s power project in Mundra, Gujarat, was extricated from bankruptcy proceedings even as its peers were not. Its SEZ in Mundra came up without an environmental clearance. Complaints about the Adani Group’s looming monopolisation in sectors like ports went unconsidered. Other inquiries, like the Department of Revenue Intelligence’s 2014 investigation into over-invoicing of imported coal, have gone nowhere as well.

Missing within this litany of favours, however, was the quid pro quo: what was in it for those who supposedly bestowed these favours? Policy favours were whispered about as a fourth pillar that lent stability to the empire but there was little proof.

Adani didn’t show up in the electoral bonds list. Apart from his Group’s disclosures on political party donations, there was little to suggest that policy-makers were benefitting by favouring the conglomerate.

With its investigation, the Securities Exchange and Commission (SEC) appears to have found that quid pro quo, alleging on 20 November 2024 that “Gautam and Sagar Adani orchestrated a bribery scheme that involved paying or promising to pay the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes to Indian government officials to secure their commitment to purchase energy at above-market rates that would benefit Adani Green and Azure Power”.

The Adani Group has denied these allegations. The SEC based its findings on whatsapp messages found on the phone of Sagar Adani (Gautam Adani’s nephew), whistleblowers, excel sheets and powerpoint slides that he and other accused maintained.

But, as our analysis shows, there are now larger implications for India, whether or not Adani manages to recover from the SEC’s charges.

The allegations that politicians were bribed is likely to shake global confidence in India’s booming renewable-energy sector. The deal has also made electricity costlier for states that may not—and already cannot—buy as much as they need, implying power cuts and higher costs for consumers; diverted money meant for healthcare and other needs; and make India’s government and economy more vulnerable, given the ever-rising dependency on the Adani Group.

Article14 reached out to the Adani Group seeking their comments. We will update this copy when they respond.

The Win-Win Contract

The SEC’s charges have been widely reported.

In June 2019, Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI), a union government company that acts as an intermediary between solar developers and India’s cash-strapped power distribution companies or discoms, floated a tender for 12 GW of solar power supply and 3 GW of solar cell and module manufacturing capacity.

It was a novel tender, combining manufacturing and solar power generation, with SECI offering to pick up four times as much solar power as the manufacturing output.

Adani Green and Azure Power, a Gurgaon-based solar developer, won the tender, with Azure getting 1 GW of manufacturing capacity and 4 GW of electricity supply or roughly equivalent to Mumbai’s peak power requirement. Adani Green was to manufacture 2 GW and supply 8 GW.

It was a big win for both firms.

Incorporated just four years earlier in 2015, Adani Green’s generation capacity had risen to 1.98 GW by the end of 2018. With this deal, its capacity would rise five-fold. The firm would also become profitable.

“(Till) that point in its corporate history, Adani Green had earned only approximately $50 million in revenue and had not recorded a profit,” says the SEC complaint. “Adani Green was projected to earn... more than a billion dollars in profit by selling power capacity to SECI.”

Azure Power was just as bullish. It anticipated, as the indictment says, over “$2 billion in profits after tax” over 20 or so years.

‘A Massive Bribery Scheme’

India’s solar power market suffers from a strange infirmity. Tenders for solar power are floated by SECI which, after finalising winners, tries to get discoms to buy the power it has already auctioned. Once they concur, SECI signs power purchase agreements with developers.

This design, created to insulate developers from the vagaries of discoms, comes with its own infirmities. Most SECI tenders don’t find takers—cash-strapped discoms, unable to shoulder the accompanying costs of intermittency, go slow on renewables; at other times, they choose to wait for solar tariffs to drop further.

In the case of the manufacturing-linked tender too, the calculations of Adani, Azure and SECI went awry. Finding the projected price from the tender too high—and expecting lower tariffs in the future—discoms refused to buy.

At this point, as the SEC says, “Gautam Adani and Sagar Adani... undertook a massive bribery scheme to incentivize Indian state government officials to enter into contracts with SECI to buy energy at above market rates”.

By July 2021, Odisha agreed to buy 500 MW in return for “hundreds of thousands of dollars”. In August that year, after Adani met then-Andhra Pradesh chief minister Jagan Mohan Reddy and allegedly offered him $228 million (Rs 1,750 crore), Andhra agreed to buy 7,000 MW from SECI.

By February 2022, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), Tamil Nadu and Chhattisgarh had acquiesed as well. The total amount paid to these five states stood at Rs 2,029 crore (about $265 million).

During this period, between 2020 and 2024, the Group went to the US to raise “US dollar-denominated financing” for Adani Green and its subsidaries. In these roadshows, the group spoke about its “anti-bribery and anti-corruption” policies—and ran afoul of the SEC which, after Hindenburg, had begun asking American institutional investors about the representations made by the Adani Group to them.

Weak Denials

As this analysis is written, most of those involved have denied the SEC allegations.

The Adani Group dismissed these charges as “baseless and denied”, and said it was “fully compliant with all laws”. Jugeshinder Singh, its Group CFO, said the complaint “relates to one contract of #adanigreen which is roughly 10% of overall business of Adani Green” and that the group would make a more detailed statement later.

Denials came from state governments as well. Tamil Nadu’s ruling party, the DMK, said it had no “direct contact with Adani firm”. So did Jagan Mohan Reddy’s YSRCP. It posted a statement on Twitter saying: “There is no direct agreement between AP DISCOMs and any other entities including those belonging to the Adani group.”

This is a weak counter-argument. As the indictment says, the states had to tie up with SECI, not Adani. And, as the purchase contract signed between SECI and Chhattisgarh State Power Distribution Company on 12 August 2021, shows, the agreement explicitly mentions Adani Green and Azure Power.

At this time, the rest of the world is taking the SEC’s chargesheet seriously. Kenya has scrapped its proposed deals with Adani. GQG Partners, which stepped in to rescue Adani after Hindenburg’s shortselling attack, saw its stock fall by 23%. It might face, reported Fortune India, an exodus of investors. It might also struggle to raise funds – which will create its own complications. In the meantime, arrest warrants have been issued for Gautam Adani and Sagar Adani.

These developments, however, are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. The bigger picture is, as we said, larger than its implications for Adani or a clutch of states agreeing to buy expensive power from Adani Green.

A Facade Is Ripped Off

The bribery scandal rips the progressive facade off India’s renewable-energy (RE) sector.

After coming to power, Modi set ambitious targets for India’s RE sector, hiking the previous target of 20 GW by 2022 to 100 GW MW by 2022. Three years later, he doubled down and expanded that target, saying India’s RE capacity would stand at 500 GW by 2030.

Their growth prospects buoyed by government pronouncements, Indian RE firms fanned out across the world to attract investors. For the most part, they were successful. Investments into India’s RE sector have been rising steeply, from Rs 20,600 crore ($2.5 billion) in 22-23 to Rs 31,500 crore ($3.76 billion) in 23-24.

These sums are significant. The global climate-change conference, COP29 is entering its final hours in Baku, Azerbaijan, as you read this. Developing countries are fighting for funds urgently needed for adaptation and mitigation. So far, commercial capital for renewable energy has been more easily available than climate reparations from the Global North.

Now, between SECI and Adani, some of those commercial flows might slow as well.

Here’s the reasoning. SECI floats a tender—spanning solar manufacturing and generation— that few RE firms can bid for. Such a project would consume greater capital expenditure than a standalone solar developer—and that the price of its power costs will be higher. As the SEC complaint says, the cost of power was known to Adani and Azure by the time the letter of award was signed.

In a fair marketplace, they would have gone back to the drawing board to redo project calculations. What they did, instead, was to allegedly pay-off regional governments and find buyers.

When firms bag PPAs despite being uncompetitive, the picture that emerges, said a Chhattisgarh-based political observer, is of a sector dominated by firms with political linkages. It will make other investors—ones which are less politically connected—think twice before entering.

As IIT Delhi professor Rohit Chandra wrote in Scroll on 21 November 2024: “What hope can foreign companies and smaller companies without access to the highest levels of politics and bureaucracy have in navigating such processes?”

This question that has gone unasked is why the manufacturing-linked tender was floated.

Higher Costs, Less Electricity

Hardwired into the SEC complaint are larger truths about the links between Indian politics and business.

Adani Green, industry analysts told SEC investigators, would earn more than a billion dollars or Rs 8,000 crore in profits. Azure Power was more bullish, anticipating profits over $2 billion or Rs 16,000 crore over 20 years.

Where would this money come from? Discoms pass these costs to their customers.

When businesses pay more for power, they lose competitiveness against peers in other states and countries whose electricity is cheaper. For families, electricity costs take up a larger share of their household budget.

As the quid pro quo shows, this cash comes from India’s electricity consumers—the vast majority of whom are poor and lower-middle class—and flows to the country’s political and economic elite.

There is more. India’s discoms are cash-strapped. If power rates are high, they will buy less electricity, which means power cuts.

This is already visible in Kashmir.

It is seeing lower power supply than demand -- partly due to decreased purchases of power from outside power generation companies by the government. The result? As winter sets in, some regions, such as Bandipora, are seeing longer outages despite power being a necessity in cold weather. Locals will have to spend on costlier diesel or wood, with the pollution and deforestation that entails.

The opportunity costs of buying expensive power run deeper yet. When discoms run into losses, they will either be privatised—with Adani amongst the firms buying discoms—or be bailed out, either by union or state governments.

This means India’s tax-payers find their taxes going, not into fresh public expenditure, but into bailing out loss-making discoms.

Each of the states that allegedly paid off Adani—J&K, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Chhattisgarh—is struggling to meet its developmental objectives. J&K, which has the worst unemployment in India, as the latest PLFS data confirmed, is already lumbered with liabilities of Rs 1.12 lakh crore.

Article 14 took a closer look at healthcare staffing in the other four states to see how well they fulfill their developmental responsibilities.

Each—Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Chhattisgarh—reports high levels of understaffing, which is usually due to low salaries which, in turn, are the result of low healthcare allocations.

Nowhere is this more stark than in Kashmir, where unelected policy-makers decided, in return for private profit, that Kashmir should pay more for power.

In all this, the country’s watchdogs—its Comptroller and Auditor General, the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Enforcement Directorate, Lokpals —have been silent.

The Centrality Of Gautam Adani

One striking aspect of the chargesheet is that two of these five states are run by opposition parties.

J&K was run by a lieutenant governor selected by the BJP when the contract with SECI was signed. In Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, CMs Naveen Patnaik and Jagan Mohan Reddy have been supporting the BJP anyway. Chhattisgarh, however, was run by CM Bhupesh Baghel of the Congress when the PPA was signed. Tamil Nadu, another building block of the INDIA alliance, continues to be headed by DMK chief M K Stalin.

More than anything else, this shows the centrality, even indispensibility, of Gautam Adani in India’s political economy.

The costs may come home soon. Donald Trump will be president of the US again. As Bloomberg columnist Andy Mukherjee wrote on 21 November, expect him to drive a hard bargain as Modi and Adani try to settle the bribery scandal.

Adani’s deficiencies, in other words, have become India’s vulnerabilities.

(M Rajshekhar is an independent reporter writing on energy, climate and India’s political economy. He is also the author of Despite The State: Why India Lets Its People Down And How They Cope)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.