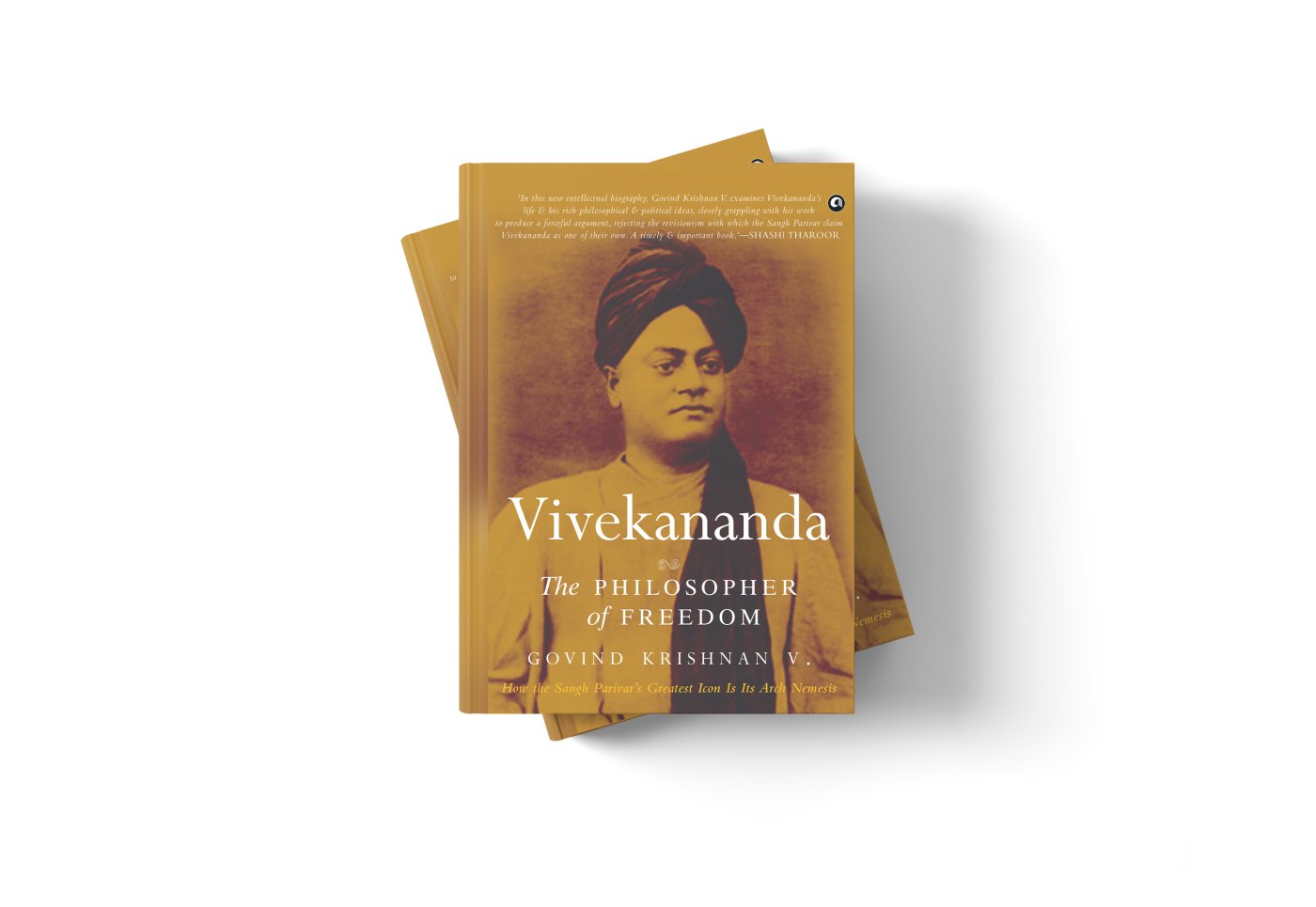

Govind Krishnan V's book, Vivekananda: The Philosopher of Freedom, challenges the Hindu right's attempt to co-opt Swami Vivekananda, undeniably one of the most influential and defining figures of modern Hinduism. The book aims to demonstrate that Vivekananda's religious philosophy, social thought, and ideology stand in contrast to Hindutva.

The first of three sections, ‘Life, Ideology, and Historical Context’, begins with a brief biography of Swami Vivekananda, then delves into how the RSS and the Sangh have appropriated Hindu symbols, motifs, and issues, in contrast to Vivekananda's approach to Hinduism. The section also explores Vivekananda's early understanding of and relationship with Islam and Christianity. It examines the clash between Vivekananda's internationalism and the RSS's nativism.

The second section, ‘Hinduism, the Sangh, and the West’, is an introduction to lesser-known aspects of Vivekananda's writings and thoughts. It explores Vivekananda's perspectives on themes such as Indian civilisation, society, culture, the caste system, Brahminism, the history of Islam in India, attitudes towards Islam and Christianity, Hindu mythology, beliefs, rituals, individual liberty, and attitudes towards the West.

The final section, ‘Vivekananda's Philosophy’, expounds on his philosophy of universal religion and his theoretical framework, emphasising his famous notion that religion should be as rational as science. Excerpt:

The letter read:

DARJEELING, 3rd April 1897

DEAR MISS NOBLE,

I have just found a bit of important work for you to do on behalf of the downtrodden masses of India. The gentleman I take the liberty of introducing to you is in England on behalf of the Tiyas (Ezhavas), a plebeian caste in the native State of Malabar. You will realize from this gentleman what an amount of tyranny there is over these poor people, simply because of their caste. The Indian Government has refused to interfere on grounds of non-interference in the internal administration of a native State. The only hope of these people is the English Parliament. Do kindly everything in your power to help this matter [in] being brought before the British Public,

Ever yours in the truth, VIVEKANANDA

Miss Noble was Margaret Noble, who would later become Vivekananda's disciple and take the monastic name of Sister Nivedita. After receiving this letter, she would initiate contact with Herbert Roberts, who was known to be sympathetic to the Indian cause, and persuade him to place the plight of the Ezhavas before the British Parliament. But the originator of the effort to enlist Vivekananda's help was a remarkable man named Dr Padmanabhan Palpu. Palpu was one of the two graduates referred to by Herbert Roberts in his parliamentary question, who had to take employment in Mysore state, because he was denied employment in Travancore due to his caste. A revolutionary anti-caste reformer as well as public health doctor, he would play a pivotal role in India's first mass anti-caste movement. Later, Palpu would arrive in London and get Dadabhai Naoroji to present the case directly to the India Secretary, Lord George Hamilton. According to many historical accounts, the combined effect of these efforts was pressure from the British Resident on the Travancore government to start making its policy regarding government jobs inclusive of Ezhavas.

The Ezhava movement was the only non-party mass mobilization by an untouchable caste in Indian history, against caste discrimination. It was also one of the first anti-caste movements in India, beginning towards the end of the nineteenth century and continuing till the 1940s.

There were many historical and social reasons why the Ezhava community (also called Thiyyas in north Kerala) was able to organize and agitate against the discrimination and oppression they faced. The Ezhavas, a large section of whom were toddy tappers, were a dominant caste which was demoted to untouchable status centuries ago. Sections of the Ezhavas continued to maintain cultural links to the Sanskrit tradition. Though rare, some Ezhavas were wealthy and titled landowners. A small section acted as physicians because of traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and herbs. The economic situation of the Ezhavas also improved substantially with the emergence of a cash economy. All these factors together placed the Ezhavas in a unique position compared to most untouchable castes in India, possessing just enough dispersed cultural and economic capital to challenge the system on untouchability, prohibition from government jobs, public schools, and colleges, from temples and their vicinity, and various other obstructions to living a dignified life.

The Ezhava movement was led by Sri Narayana Guru, a sanyasi who belonged to the Ezhava caste, but was a Vedantist and a Sanskrit scholar. In 1903, Palpu established an organization to fight for the rights of Ezhavas called the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP).

Other than Narayana Guru and Palpu, the most influential figure in the Ezhava movement was probably Kumaran Asan, the legendary Malayalam poet who introduced romanticism into Malayalam poetry.

Though Vivekananda's views on caste have been the subject of revisionist history, his own contemporaries, both friend and foe, considered him an anti- caste reformer. This was mainly due to several speeches he delivered to massive audiences where he called for an end to caste privileges and to untouchability, and rebuked Brahmins for priestcraft and their oppression of the masses. The orthodox section of Hindu society repudiated his attacks on the caste system and disputed his assertion that Hinduism did not sanction caste and that it was simply a social custom which had received the sacerdotal backing of priests intent on preserving their privileges. The most tangible effects of Vivekananda's discourses and actions were on the Ezhava movement.

When Vivekananda visited Mysore in 1892 before his journey to America, he met Palpu, who was working as a doctor for the Mysore government.

Palpu appraised Vivekananda of the rampant caste discrimination that pervaded Kerala and the problems faced by the Ezhavas. Vivekananda advised Palpu not to look for help from the upper castes. Vivekananda's view, which he would later expound in public, was that no social reform movement would succeed in India, except through the vehicle of religion. Vivekananda instructed Palpu to find a spiritual master of his own caste and build a movement under his leadership.

Palpu was convinced and, four years later, he had his fateful meeting with Sri Narayana Guru.

Narayana Guru had already started establishing temples for Ezhavas. With Palpu providing financial help and organizational leadership, Narayana Guru's spiritual movement became an umbrella for Ezhava consolidation and social and caste reforms. Robbin Jeffrey, a historian who specializes in the social history of modern Kerala, writes: 'Shortly after Palpu took up service in Mysore, Vivekananda visited the state. Palpu appears to have got to know him well, and many of Vivekananda's teachings were to find their way into the Ezhava movement as it developed at the turn of the century. Palpu became receptive to the idea of Hindu revivalism and reformation.'

When Vivekananda landed in India in 1897 after his success in the West, he delivered a dozen speeches in various places in Tamil Nadu, including several at Madras. By several contemporary and later accounts, they created a perfect firestorm in the collective consciousness of English-educated Hindus in the south. Vivekananda used these occasions to powerfully preach for creating a fraternal national consciousness, for a Hindu spiritual revival, reforming Hinduism and for the equality of all castes.

The Ezhava leader most inspired by Vivekananda's thought and whose own writings acted as a channel for the monk's ideas into the Ezhava movement, was Sri Narayana Guru’s protégé Kumaran Asan. Asan, who served as the general secretary of the SNDP since its formation in 1903, for seventeen years, was also the editor of the SNDP's journal. The journal was named Vivekodayam in tribute to Vivekananda. Kumaran Asan translated Vivekananda's poem 'And Let Shyama Dance There' from Bengali to Malayalam; it appeared in two issues of Vivekodayam. Kumaran Asan later translated Vivekananda's seminal book Raja Yoga into Malayalam.

The great agitations and triumphs of the Ezhava movement and the SNDP came in the three decades after Vivekananda's death. Even before Independence, untouchability was banished from public spaces and people from the lower castes gained representation in government jobs as well as political representation, and the right to enter temples. Next to Sri Narayana Guru's own preaching, Vivekananda's thought seems to have remained an integral component of the SNDP's spiritual and social outlook. Writing in the post-Independence era,

P. Sugatan, an early Ezhava trade unionist leader and later communist party member who had been part of the SNDP wrote, “It was Swami Vivekananda who made us aware of our slavery and inspired us for national freedom. The wonder of it was that he did it through his religious and spiritual talks and lectures. It was Swami Vivekananda who first loudly proclaimed that without the removal of caste, poverty and ignorance of the masses, Indian freedom is an impossibility."

Vivekananda has been lately criticized as being sympathetic to the caste system or even lending support to it, and as an upholder of upper-caste hegemony. I think one thing we can be certain about is that if any of these are true, then Vivekananda must have been a fantastically poor communicator of his ideas.

In the several areas in which Vivekananda has been the object of criticism, the only subject regarding which his exact views would appear to have a certain amount of ambiguity at first blush, is that of caste. In and of itself, there is nothing exceptional in such ambiguity. With any thinker there are always issues which belong to the periphery of their main thought, and hence would not have been considered at length and given theoretical elucidation. Just like caste, there are several subjects like nationalism, the question of India's political independence, patriotism, democracy, socialism, the idea of historical progress etc., where Vivekananda's views are not easy to ascertain exactly. This issue occurs with most thinkers. But in Vivekananda's case, there is, I suspect, a tendency to underestimate the need to analytically extract his theoretical position on peripheral subjects because of the sheer simplicity, crispness, and concise nature of his language. This often gives the erroneous impression that a simple view of a matter is being presented briefly. In the case of caste and certain other subjects especially, brief and scattered remarks are only the surface of deeper and more complex views.

(Excerpted with permission from Vivekananda: The Philosopher Of Freedom, published by Aleph Book Company.)