New Delhi: In April 2018, over 3,000 fishing collectives, environmental groups and citizens across India submitted their objections to the draft of the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, the law that governs the development of the country’s 7,500-km coastline. Nine months later, disregarding over 90% of representations—in violation of the February 2014 Pre Legislative Consultation Policy—and without publishing the draft in the official gazette as mandated, the government pushed through the final notification, according to documents reviewed by IndiaSpend.

Fishing collectives and environment groups objected to the notification, which opened up India’s coastline for enhanced commercial activities, primarily on the grounds that:

1) No prior consultation was held with coastal communities, especially the fisherfolk;

2) The lifting of development restrictions would be disastrous for the coastal environment and the traditional communities that live off it;

3) Interfering with ecologically sensitive coastal areas would leave them more vulnerable to natural hazards.

The new law lifted the prohibition on construction in the previously protected 200-metre no-development zone (NDZ) in rural areas and 100-metre NDZ along tidal-influenced water bodies, reducing it to 50 metres for these water bodies and densely populated rural areas (with a population density of 2,161 per sq km). This would make way for more real estate, hotels and beach resorts, exposing more lives and property to the danger of extreme weather conditions, the groups argued. Amendments brought between 2014 and 2018, and retained in the new law, also allow for activities such as mining of atomic minerals in CRZ areas and reclamation of sea for monuments and memorials.

Sand dunes and mangroves provide the much-needed buffer against cyclones and storm surges. Yet "eco-tourism" constructions and activities are now allowed in vulnerable areas, as is mining for rare earth minerals in sand dunes and waste treatment in sensitive inter-tidal areas.

“Yeh lokshahi nahi thokshahi hai (this is not democracy, this is governance by force),” said Kiran Koli, general secretary of Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti, a Mumbai-based fisherpeople's collective, about his and 352 of his fellow members’ views being ignored by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC).

The CRZ notification is critical to the lives and livelihoods of the communities--around 171 million people or 14% of India’s population--living across 70 coastal districts, 66 in mainland India and four in island territories. Their future, especially that of marginalised communities, is directly linked to the health and disaster preparedness of the coasts, as IndiaSpend reported in October 2019.

If the ecological services of the coasts such as the maintenance of water balance, control of erosion and waste processing are factored in, it becomes even more important to ensure the health and resilience of coastal areas.

Upto 36 million Indians are likely to encounter coastal floods due to rising sea levels by 2050, an October 2018 study released by Climate Central had predicted. Urbanisation can increase the flood peaks up to eight times and flood volumes by six times, according to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA).

Allowing intense development closer to the sea would exacerbate the risk for the coastal infrastructure and vulnerability of coastal populations, according to a paper released in August 2019 by the Observer Research Foundation.

Yet, the notification allowed for higher floor space index or floor area ratio—that is, more covered area, including all floors, in a property—for buildings in disaster-prone urban areas. Many of these urban areas are densely populated cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Vishakhapatanam and Chennai.

IndiaSpend emailed a detailed questionnaire to the joint secretary, CRZ, MoEFCC on 30 January, 2020 seeking the ministry’s explanation for these omissions. This was followed up with two phone calls over 25 days. However, we did not get any official response to our queries. This story will be updated if and when we receive a reply.

3,469 Objections To Draft

The MoEFCC published the draft CRZ notification on its website on 19 April, 2018. This draft was prepared on the basis of representations from coastal states and ‘other stakeholders’ and recommendations of the Shailesh Nayak Committee, set up to review the CRZ law of 2011, the government stated.

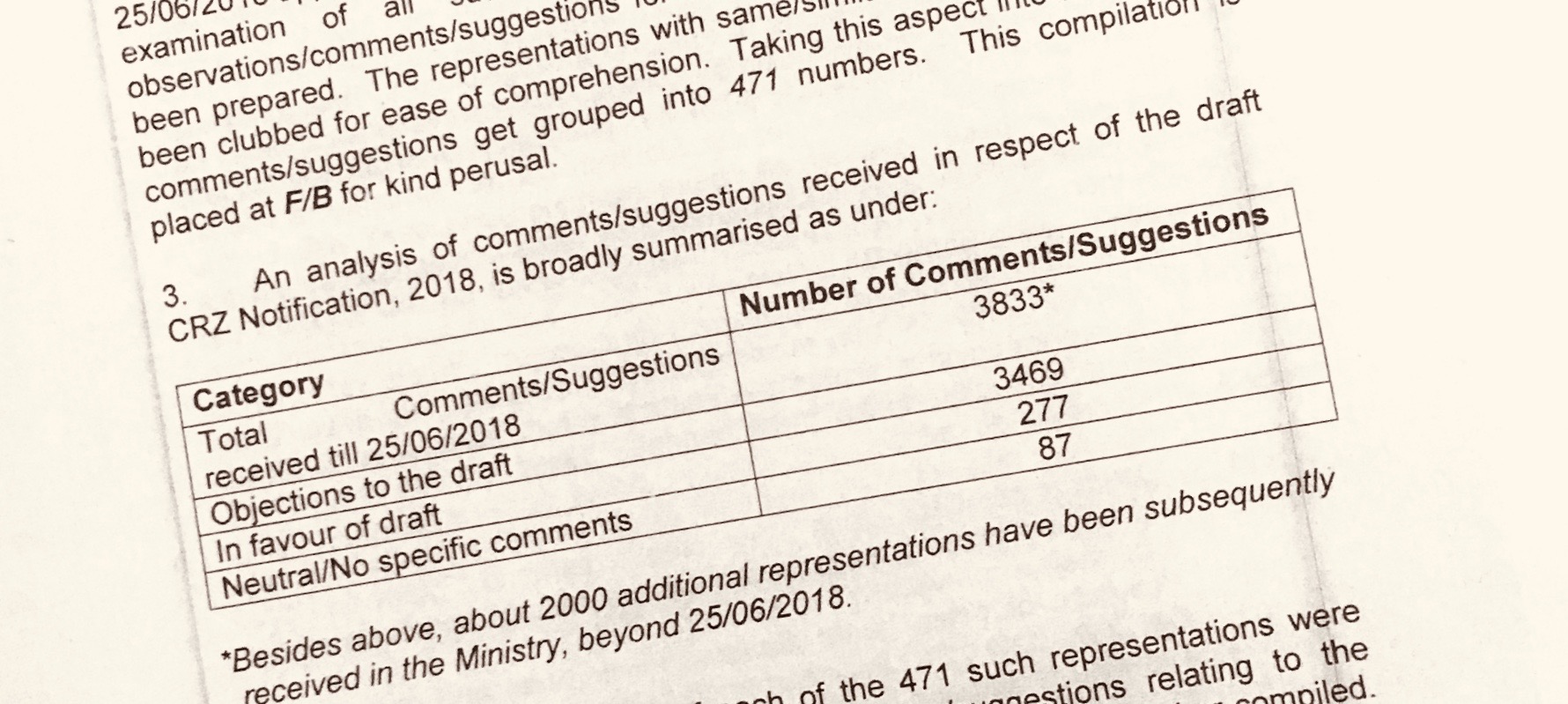

The draft was open for two months for public responses. The ministry received 3,833 representations, of which 3,469 were objections to the draft, documents obtained through a Right to Information (RTI) application revealed.

The ministry, finalising the law in January 2019, argued that the objections did not warrant attention because they “principally” fell within the set of concerns already addressed by the Nayak Committee, constituted in 2014. But this panel did not meet with the public while reviewing the law, and submitted its report in 2015.

On the non-publication of the draft notification in the official gazette, the ministry countered that this purpose was served by uploading the draft on to its website. However, publication of draft laws only in the administrative ministry's website does not facilitate the kind of discussion and engagement such laws deserve, observed an August 2019 analysis by public policy researchers Arun P S and Sushmita Patel.

Review of 2011 notification

The CRZ notification was first promulgated in 1991 for the protection of the coast. Over the following decade and a half, the notification went through eight reviews and 20 amendments. To compile these amendments in one document and to address the long-standing demand of fisher communities for recognition of their livelihood, the notification was replaced by a fresh law in 2011, according to a blog post by Centre for Policy Research (CPR), a think-tank in Delhi.

In June 2014, the environment ministry constituted a committee under the chairpersonship of Nayak, the erstwhile secretary of the Ministry of Earth Sciences.

The panel’s scope included addressing concerns raised by the state governments, eliminating ambiguities and simplifying clearance procedures. The committee held consultations with the state governments over the following six months and submitted its report to the ministry in January 2015.

While the ministry did not make the committee report public, it started chipping away at the notification’s progressive clauses by incorporating the changes suggested by the panel—such as the lifting of certain restrictions on the construction of buildings in coastal towns, allowing mining of atomic minerals even in intertidal areas, and reclamation to build monuments and memorials.

Between November 2014 and July 2018, 14 amendments were made to the CRZ law, four as drafts available for public review and ten as final amendments. The 2018 draft not only pieced together all the amendments, it also proposed further dilutions such as reduction of the NDZ and eco-tourism structures in ecologically sensitive areas, several stemming from the committee’s suggestions, according to an analysis by CPR.

‘Committee Sought No Public Inputs’

In an interview in 2016, Shailesh Nayak had stated that the committee had met with the chief minister of Kerala, the chief secretary of Maharashtra and senior government officials of all coastal states and union territories. The panel had met with “other stakeholders” as well, the environment ministry had claimed repeatedly. But Nayak categorically denied meeting anyone other than state officials.

“The committee worked in an opaque and exclusionary manner, seeking no public inputs,” remarked Kanchi Kohli, senior legal advisor at CPR.

Nayak also denied receiving submissions from NGOs and other groups during the review. However, think-tanks and NGOs countered that they had made submissions with requests for meetings. “I sent him numerous emails requesting that we be given a hearing by his committee, and he refused to do so,” said Debi Goenka, executive trustee with Conservation Action Trust, a non-profit organisation based in Mumbai.

In these consultations, state governments sought reduction in the no-development zone, relaxations for tourism and mining activities and the extension of existing town and country planning norms to urban constructions in coastal areas as well, according to a summary of states’ representations prepared by CPR. The committee turned these demands into suggestions which were eventually made part of the new law.

“If you look at his report, it is evident that all that his committee did was accept almost all the demands of all the state governments to dilute the CRZ,” Goenka said. “Concerns of coastal inhabitants, fisherfolk, NGOs, etc. were not really relevant to his committee.”

The committee presented its initial findings before the ministry in November 2014 and submitted its report in January 2015. Coastal communities, citizen groups, scientists and the general public remained unaware of these developments. The Central Information Commission had to direct the ministry to share the report with CPR’s Kanchi Kohli, who had filed an RTI application and followed it up with first and second appeals for a copy of the report.

But the ministry, through its justification for ignoring the objections to the draft, implied that the Nayak committee had “dealt with” public concerns even before they were raised.

“It is a travesty of justice when the ministry claims that all the objections raised by the public in due earnestness had already been addressed and resolved by the committee's process,” said Kohli. “The Shailesh Nayak committee report has still not been officially made public by the environment ministry.”

Government Overlooks Its Own Policies And Rules

As the second consecutive term of the United Progressive Alliance government at the Centre was drawing to a close, in February 2014, the ministry of law and justice had promulgated the pre-legislative consultation policy. The policy was a result of a meeting of a committee of secretaries of the outgoing regime held in 2014. It also incorporated the recommendations of the National Advisory Council, an advisory body created by the UPA government in 2004 that ceased to exist under the current regime and the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution.

As a step towards “transparent government”, it suggested a set of practices to be followed “invariably” by all ministries and departments before finalising a legislation. Besides advising that the proposed law be published through the internet and “other means” for a minimum period of 30 days, the policy recommended that the summary of feedback received should be made available on the website of the ministry concerned.

The environment ministry did not upload the summary of comments received on the draft CRZ law on its website. The comments were obtained through an RTI application and made available by the CPR on its website.

For laws that could impact a specific group of people, the policy had suggested that the law should be made available in such a manner that it gives “wider publicity to reach the affected people”. Also, to “enable wider comprehensibility”, draft policies should be made available in regional languages but it is often not the case, commented scholars Arun and Patel.

As a good practice, the policy also recommended that the ministry concerned could hold public consultations in addition to making the draft available in the public domain, the degree and mode of which it could decide. This was not done.

There were no such gaps in the process when CRZ 2011 was being drafted. Extensive consultations were held with numerous stakeholders on several contentious issues at the time. “In 2010, more than 10 consultations were conducted, in all coastal states and UTs,” recalled T Peter, secretary, National Fishworkers’ Forum. “The final law of 2011 did not include everything that we sought. But it had addressed several of our concerns.”

Clause 5 of the Environment (Protection) Rules, 1986 empowers the central government to impose any restriction regarding the location of certain industries or operations. It is on the basis of this provision that the environment ministry issued laws such as the very first version of the CRZ notification of 1991 and subsequent iterations of 2011 and 2019, and Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006. Sub-clause (3) of this clause specifies that the government can bring in such stipulations “by a notification in the Official Gazette”.

But the ministry did not publish the draft in the gazette.

“Results of public consultations are legally non-binding but if the draft CRZ notification was not published in the gazette it is a violation of the environment protection rules,” said Rahul Choudhary of Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment, an NGO in Delhi.

The non-publication of the draft in the official gazette may be considered an “exceptional case”, the ministry said, as it had been uploaded on its website.

Thousands Of Fisherfolk Are Ignored

Of the 3,833 representations made against the 2019 notification, over 2,000 were from fisherpeople’s collectives, all of which rejected the draft, the compilation of comments on the draft shows. “The Shailesh Nayak Committee did not consult us,” said Debasis Pal, a Rajahmundry-based social activist and general-secretary of the Democratic Traditional Fishers’ and Worker Forum, Andhra Pradesh (DTFWF).

DTFWF alone sent 1,500 representations rejecting the draft. “The draft did not come in vernacular,” Pal said. “How many of the fishers are literate or can understand English/Hindi?”

Besides the fisher groups, another prominent actor in coastal governance was kept out of the review process—the State Coastal Zone Management Authorities (SCZMAs). These bodies are responsible for implementing the CRZ Notification in their respective states/UTs. They coordinate the preparation of coastal management plans, appraise project proposals, identify and assess CRZ violations, and take measures for conservation of ecologically important sites.

Antonio Mascarenhas, scientist at the National Institute of Oceanography and until 2016 a member of the Goa SCZMA, has expressed his disappointment with the CRZ review exercise. His was one of the 3,469 submissions that rejected that draft law. In support of his submission to the environment ministry, he provided a set of academic papers and stated “these seven scientific papers may please be considered so as to understand coasts need to be protected and not opened up for indiscriminate commercial use”.

Yet, the ministry went ahead.

“The CRZ is a critical regulation for conservation and livelihood protection on the coast,” said Kohli. “CRZ 2019 stands as a testimony of a perfunctory exercise to achieve an objective that was fait accompli from the outset.”

(Meenakshi Kapoor is an independent environment policy researcher.)