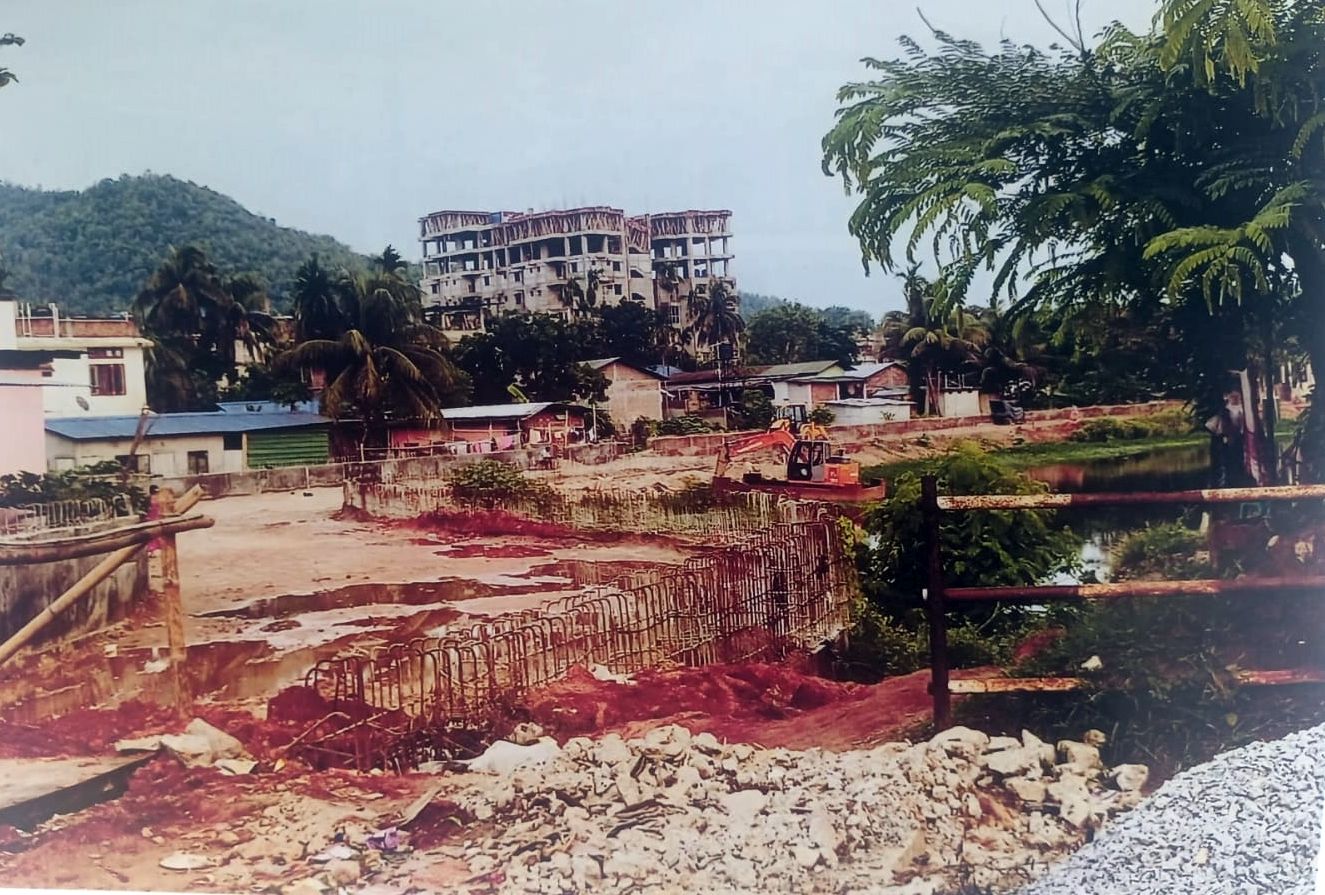

Guwahati: Anwara Begum, 57, picked up one brick after another from the rubble that was her house near Silsako Beel, a wetland in the eastern part of Guwahati, Assam.

Anwara had purchased the land for Rs 20 lakh in 2020 and spent another 50 lakh to build the house. The Guwahati metropolitan development authority (GMDA) demolished her pucca house over two days on 11 and 12 September. After the demolition, she tried to salvage anything that she could sell and recover some money from the rubble of her house.

“We built it with our hard-earned money through daily wages. They did not serve any notice, we could not even save anything,” said Anwara.

Anwara’s family is one of at least 900 families in Silsako wetland the GMDA has evicted local activists estimated over the last two years as state authorities bulldoze permanent and temporary structures to clear “encroachments”.

This reporter walked the one-kilometre area of the latest demolition in September, and, like Anwara’s, house after house with Guwahati municipal corporation (GMC) holding numbers, proof they paid GMC tax and electricity connections had been demolished.

But that did not stop authorities from bulldozing the houses at Silsako even as affected families protested, claiming that the authorities gave the settlement legitimacy by providing GMC holding numbers and electricity connections.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government sanctioned the improvement of a road at Silsako in the past seven years. Moreover, a BJP MP from Guwahati, Queen Oja, inaugurated a road at the wetland.

Following protests demanding compensation in September, the government sanctioned Rs 75 lakh for ten houses; the owner of an RCC (reinforced cement concrete) house got Rs 10 lakh, and the owner of an Assam-type house ( single-storey, walls are made of bricks and concrete, roofing is done with tin sheets) got Rs 5 lakh.

Later in the month, the government-sanctioned another Rs 2.75 crore to compensate 31 families. The compensation amount would reportedly be distributed among owners of 14 RCC buildings and 17 Assam-type houses.

Activists said most people evicted in the last two years have not been compensated, but Article 14 cannot independently verify this.

In November, Anwara, who received Rs 10 lakh as compensation, said this amount does not cover the entire loss incurred during the forced eviction.

“We demand our land back,” said Anwara’s husband Rahman.

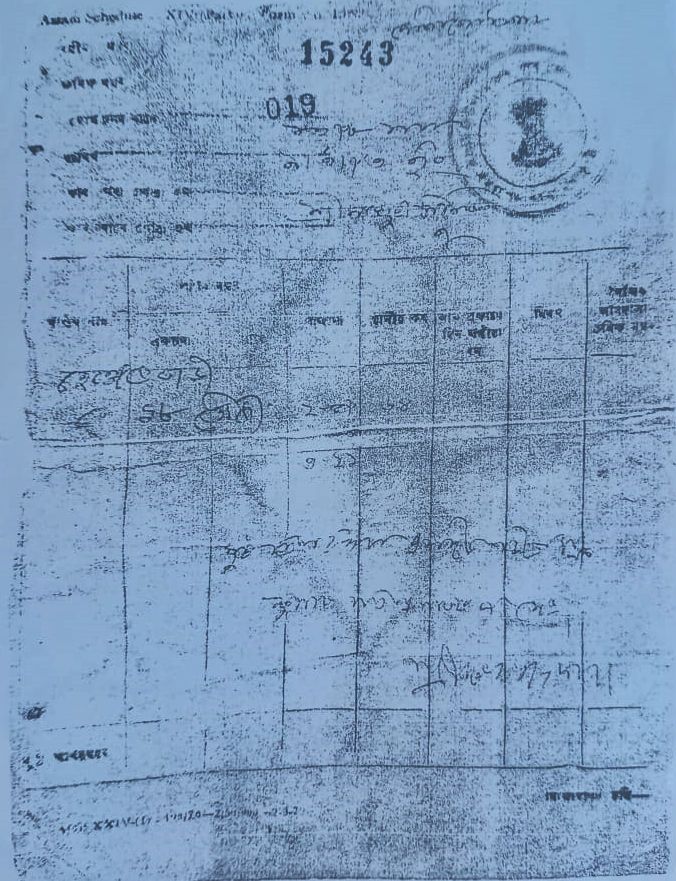

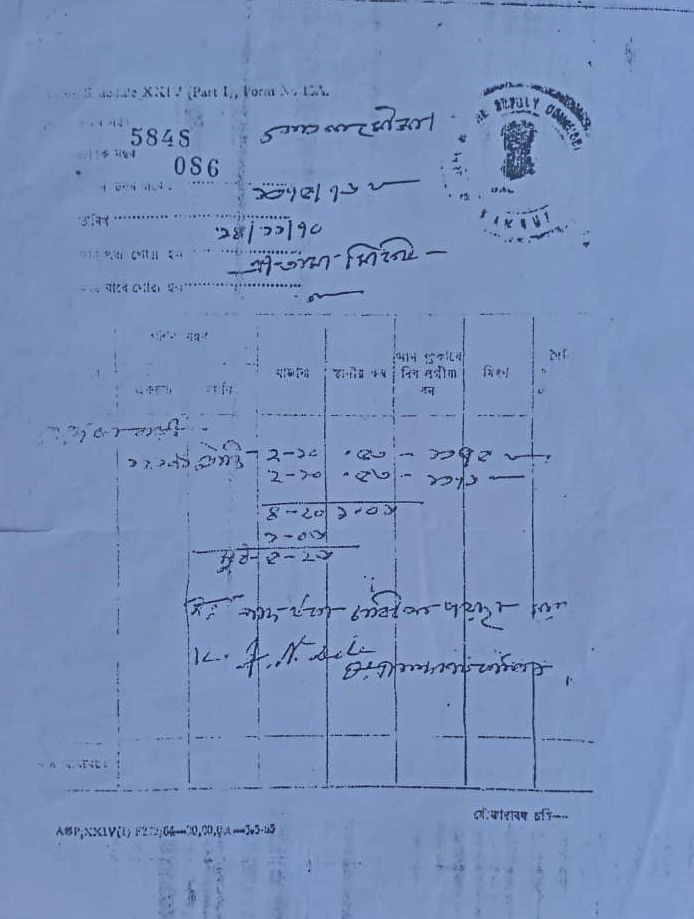

Article 14 has seen tax bills and receipts related to GMC, as well as electricity bills and receipts of three evicted families, which include Pateswari Singha's GMC tax receipt (2017) and electricity connection receipt (2018); Bhaben Deori's tax bill (2023) and electricity bill (2018), and Jaymati Choudhury's electricity connection receipt (2007), GMC tax bill (2016), and electricity bill (2019).

A Crime To Encroach Wetlands

Wetlands—areas with static or flowing water, natural or artificial, regardless of salinity, including marine zones less than six metres deep at low tide—see conservation efforts as they are essential to the water cycle, boasting high productivity, rich biodiversity, and offering various services like water storage, purification, flood mitigation, erosion control, etc.

The Silsako Beel is notified under a 2008 state law, the Guwahati Waterbodies (Preservation and Conservation) Act, which prohibits garbage dumping, earth-filling, and construction activities in the notified areas. Any violation under it is “treated as cognisable offences” under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. It is punishable with a maximum punishment of three years or a fine of up to Rs 50,000 or both.

The land was used by tribal farmers, mainly from the Karbi community, who cultivated rice on the wetland. Assamese and Bengali people and other tribal communities, including the Mising, Bodo, Rabha, Dimasa, and Deori, settled in this area.

For nearly three decades, successive governments have allocated land to institutions and companies that sanctioned the building of roads like Sanjivani Path and improved the existing ones like Pub Shrimanta Shankar Nagar Road.

Before the Waterbodies Act 2008, GMC reportedly used Silsako as Guwahati's main garbage dumping site.

The BJP state government, which has been in power since 2016, claimed that 396 acres of the 595 acres wetland are encroached.

The state administration has undertaken at least four eviction-demolition drives on the Silsako wetland, with the latest one in September 2023.

These evictions were carried out under the Waterbodies Act of 2008, citing the administration’s effort to “make Guwahati flood-free”.

The Act permits the GMDA to protect the water bodies—Sarusala Beel, Silsako Beel, Borsola Beel, and Deepor Beel—from encroachers and damage. It also allows the development of the water bodies into natural water reservoirs and eco-tourism recreation centres.

Our Home For Decades: Locals

Local communities protested the drives, for they have lived here for decades even as the government gave legitimacy to these settlements by building roads and services and collecting taxes.

They alleged the government had driven the poor from their homes while properties owned by influential and private companies remained untouched.

When Himanta Biswa Sarma was the Guwahati development department minister during the Congress government from 2006-2011, the Ginger Hotel was established in 2009 by the Indian Hotels Company Limited (IHCL), a subsidiary of the Tata Group on Silsako’s land.

As the minister of the public works department (PWD) in the BJP government, Sarma in 2019 approved funds under the state-owned priority development (SOPD-G) for the improvement of the Pub Shrimanta Shankar Nagar road in Silsako, part of which runs through the area evicted in September. Now, as the chief minister of Assam, the poor people living there claim he has evicted them without rehabilitation.

In 2019-20, Queen Oja, a member of Parliament from Guwahati, inaugurated the construction of the Sanjivani Path. It was constructed using government money from the Members of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme (MPLADS) fund.

Govt Made Settlement Legal, Then Evicted

“While allocating this road, whom was the chief minister inviting [to live there]?” said Bidyut Saikia, KMSS general secretary, in a press conference after the evictions. “Why didn't Himanta Biswa Sarma say that this is the bank of Silsako and don’t settle here? On what ground was this allocated?”

Saikia said the government legitimised the settlement by “providing holding numbers, electricity and roads. In a video that surfaced in September,

Himanta Biswa Sarma is heard saying they will give patta or land deed to those living on government land, but where and when the speech is from is unclear.

On 13 May 2022, another drive evicted nearly 100 families.

On 27 February 2023, authorities carried out an eviction on the Silsako wetland that affected at least 300 families.

Following the eviction drive at Silsako in February 2023, multiple writ petitions filed in Gauhati High Court claimed long-term occupation, paying GMC taxes and electricity bills, contested eviction without notice and argued against the legality of the Waterbodies Act of 2008. The Act does not mention anything about notices. Section 9 of the Act gives power to the government to make rules. However, to date, the government has laid out no rules.

The advocate general of Assam, Devajit Saikia, defended the eviction, citing public interest due to “encroachments” affecting water bodies and causing “artificial floods”.

The High Court, interpreting settlement rules of Assam Land and Revenue Regulation 1886, which the petitioners cited as the authority for sending notices, found the government was not required to send legal notice under the law.

The state is not required to send notice if the land falls under specific categories like “government khas land”, wasteland, or land reserved for public purposes, as specified under rule 18(2) of the Settlement Rules under Assam Land and Revenue Regulation 1886.

In Rameswar Rai vs State of Assam (2001), a single bench of Gauhati High Court emphasised the necessity of a notice under rule 18(2) of the Settlement Rules under Assam Land and Revenue Regulation, 1886.

The court dismissed the writ petitions in March 2023, stressing the “larger public interest” and that it “cannot ignore the aspect of artificial floods” in the city.

Article 14 has previously reported on demolition in Delhi and UP (here, here, and here), where people alleged demolitions and evictions without receiving notices.

House Demolished Twice In 3 Years

While considering an application by a Delhi-based organisation of Islamic scholars, the Jamiat Ulama-I-Hind, following the demolitions in Uttar Pradesh in June 2022, the Supreme Court in Jamiat Ulama I Hind And Anr vs Union of India and others (2022) said that “demolitions can't take place without notices”.

In Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation and others (1985), the Supreme Court examined the displacement of the pavement dwellers in the Bombay Municipality. It recognised the rights under Article 21 and Article 14 of the Constitution, noting that “persons who are likely to be affected by the proposed action must be afforded an opportunity of being heard as to why that action should not be taken”.

After the evictions in September, Article 14 visited the eviction site comprising Pathar Quarry, Hengrabari and Barbari.

Most evictees have left the wetland, moving either to rented houses or a relative’s houses.

Joymoti Chowdhury, 53, who had to leave her home thrice because her house was partially demolished three times in two years, said she had not received any compensation and struggled to pay the rent of the house she is staying in these days.

“My son is sick,” said Chowdhury as tears welled up in her eyes. “We need Rs.10,000 for him every month, and the whole responsibility is on me.”

Land Given To Companies & Institutions

The Congress-led Assam government declared Silsako a protected wetland in 2008.

In July 2014, when the Congress was in power, an eviction drive was carried out at the Silsako wetland, tearing down at least 55 houses, including 14 concrete houses and 41 temporary houses mostly made of bamboo and 13 boundary walls in an 11-bigha area.

This was done after the city saw intense flooding, a dilemma that the city witnesses every year. But no such actions were seen in the case of the structures on land allotted to institutions and companies.

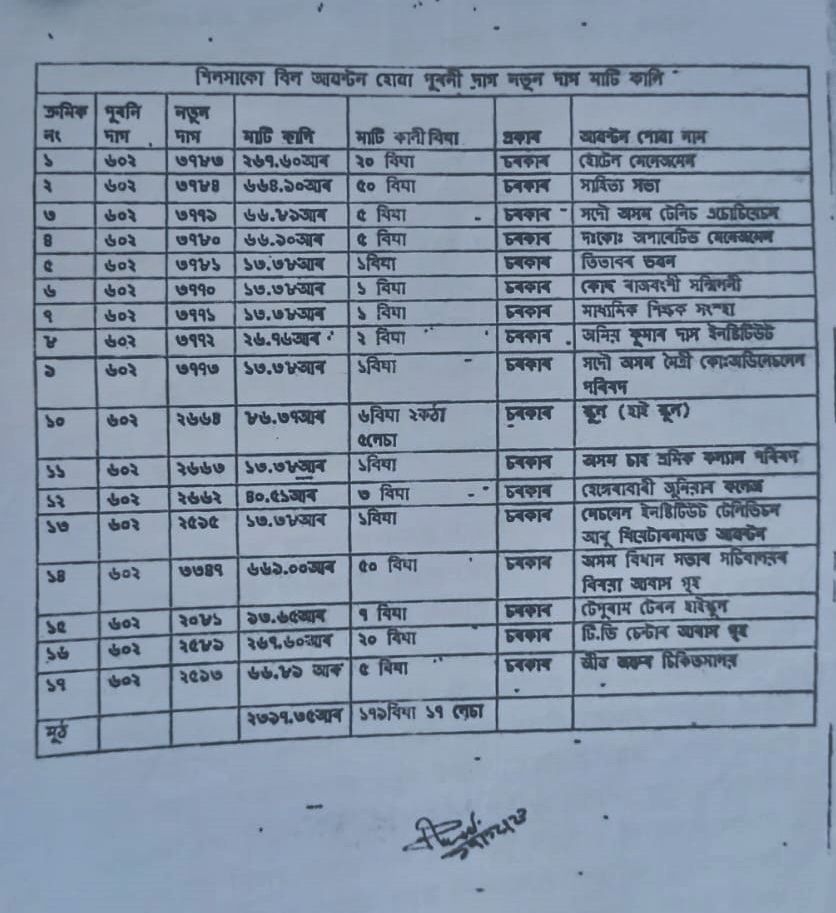

From time to time, the Assam government allotted 179 bighas of land to 17 institutions and organisations, including Ginger Hotel (owned by Tata Group’s Indian Hotels Company Limited), Omeo Kumar Das (OKD) Institute of Social Change and Development (an autonomous research institution), on the Silsako wetland.

From 2006-2011, Chief Minister Sarma, who now opposes the “encroachment” of Silsako, was a minister of the Guwahati development department in the Congress-led government, which oversees the GMDA and releases funds for public works.

On 1 March, Sarma tweeted that he instructed the District Commissioner, Kamrup (Metro), to take steps to immediately “shift institutions like Ginger Hotel, the OKD Institute of Social Change, etc. from Silsako.”

Eight months later, no such actions are visible on the ground.

In September, Assam's chief minister said that Ginger Hotel, OKD Institute, and the Tourism Institute would vacate the land, claiming that the government has “already served them land acquisition notices”.

Sarma said that Ginger Hotel took possession of the land following an order of the previous Congress government and that alternative land would be provided for both Ginger Hotel and the OKD Institute.

“The process is underway. We will vacate these lands before the next flood season,” the CM was quoted by The Sentinel as saying.

Guwahati-based Advocate Avilash Mihir Baruah said the government allotted the land to the institutions and companies without selling it, and they could take it back.

“Allotting the land does not change the status of land as the government did not sell the land to these institutions…the government is now acquiring the land,” said Baruah.

A similar observation was made by Gauhati High Court after the All Assam Tennis Association, one among the 17 institutions, approached the court against the requisition of the allotted land (five bighas allotted in 1999 and another three bighas allotted in 2003) by the Asom Gana Parishad government and the Congress government.

The court observed that “the requisition proceeding cannot be said to be not tenable because, in land revenue records, the land is still government land because the said land was never settled in favour of the petitioner.”

‘Biased Eviction Drive’

Gayatri Bori, a 36-year-old activist whose house was also demolished, called it a “biased eviction drive”.

“They are saying if they are to demolish Ginger Hotel, it has to be shifted beforehand. Then why were we not shifted before eviction? In such a case, we would not have protested. Wherever you go in this world, before eviction, a notice is served, but in our case, no notice was served,” she said.

The evictees and activists also spoke of the properties near the Silsako wetland which escaped the bulldozer.

Land allotted to Hamza Properties, an entity owned by Rezwana Ajmal, the wife of MP and the All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) chief Badruddin Ajmal, and Ideal Hill View, a residential project owned by the chairman of the Ideal Group Srawan Kumar, were not touched by the authorities.

Akash Doley, claimed that Ajmal was allotted nearly 19 bighas of land, exactly on Silsako’s bank.

Article 14 tried contacting Badruddin Ajmal over the phone, but was unavailable. An email with queries was sent to the AIUDF chief on the allegations and claims around his properties at Silsako. The story will be updated if he responds.

“Ajmal, too, has Myadi patta land [land allotted by the government] here, which is hardly 50 metres from the beel. Himmatsingka’s Ideal Hills View’s main pillar directly touches the Silsako. And as soon as the bulldozers reached near those structures, they announced that eviction had stopped,” said Bori.

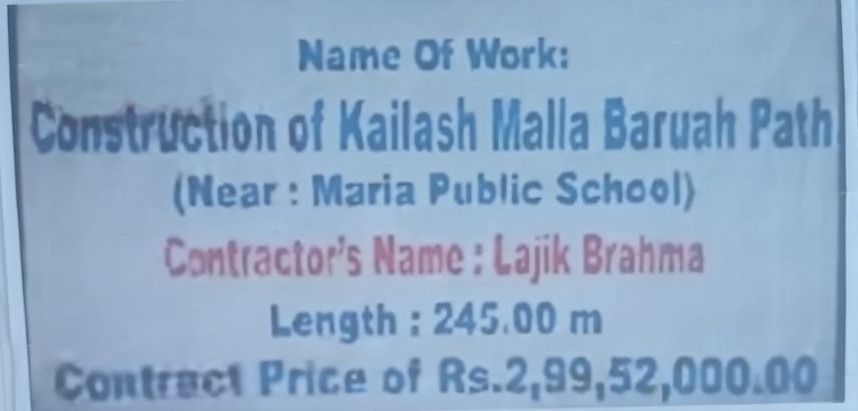

Locals and activists also point out that a road, Kailash Malla Baruah Path, named after cabinet minister Jayanta Malla Baruah’s father, Kailash Malla Baruah, was built by filling up Bondajan, a waterbody connected to Silsako, with a government budget of Rs.2.99 crore.

“If the government can fill Bondajan to construct a road for their minister, why can’t they provide land to the “indigenous” Assamese people?” questioned Aman Hazarika, a city-based activist.

Hazarika said that the government bulldozed the houses of the poor, whereas Ginger Hotel, Ideal Hills View, and Ajmal’s land remain intact.

“Why have the authorities not bulldozed these apartments till this day? These things prove that this government is not for commoners but for the capitalists. There is nothing other than this,” said Hazarika.

No Response From The State

Article 14 reached out to Ashok Singhal, the minister of housing & urban affairs and irrigation, the GMDA CEO Anbamuthan MP, and Pallav Gopal Jha, Kamrup (Metro) district commissioner and chairperson of Kamrup (Metro) district disaster management authority (DDMA). They were unavailable for calls to the landline numbers on their official websites. The district commissioner did not respond to calls on his mobile phone.

Emails with questions were sent to Singhal, the GMDA CEO, and the district commissioner on the allegations of unfair compensation and biased eviction.

Until the publication of the report, no response was received.

Article 14 also reached out to the chief minister’s office, which gave a number to his private secretary, but our call was not received. An email with a set of questions was also sent to the CM.

Land Used For Farming

A larger area in and around the Silsako Beel was notified under the 2008 Act. Evictees and activists working with local communities have questioned the notified area.

They argued that a major portion of the land was used by tribal farmers, primarily from the Karbi community, who cultivated paddy on the land. In the past four decades, people from other ethnic communities, including the Mising, Bodo, Rabha, Dimasa, Deori and Assamese, settled in this area.

This has been corroborated by at least ten evictees to whom Article 14 spoke.

The administration, however, maintains that the entire area is of the beel and that people are “encroachers”, whereas evictees claim this to be a home to indigenous communities historically.

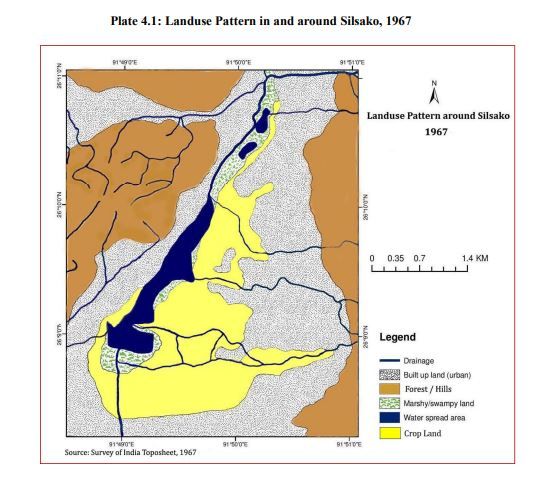

The evidence of vast cropland present over the Silsako wetland area is also proved by a Survey of India toposheet from 1967, as sourced in research related to Silsako and Borsola wetlands in Guwahati by N. Memma Singha, who was pursuing a PhD at the Northeastern Hill University in Shillong, Meghalaya.

The map mentions that “there was around 2.96 km² area used for agricultural activities.”

The same research mentions that “though the total area of this wetlands complex was measured to be 2.70 sq km (Toposheet, 1967), the toposheet of 1912 recorded the total area to be 4.09 sq km (Toposheet, 1912).”

In 2005, the wetland area was reduced by “rapid population growth, encroachment, construction works, earth filling, intensive fishing and disposal of solid organic and inorganic waste into the wetland" to 2.10 sq km. In 2011, it was further reduced to 1.13 sq km, with an overall decline of 115.50% from 1967.

Akash Doley, an activist with Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti (KMSS), a peasant organisation in Assam, who has been working for the Silsako evictees, termed the eviction of the “indigenous people” as an act of barbarism.

Doley said that many of them had been paying khajna (a land revenue tax) since 1970, and many others had applied for registration of their land in the 1970s onwards and even in the 1990s.

“Even after this, the government did not give land rights to these people. Instead of allotting land, the government introduced the Guwahati Waterbodies Act of 2008. After the inception of the Act, authorities stopped taking ‘khajna’. And after that, no decision to resettle the people was made,” said Doley.

A House Built During The Pandemic

On September 1, several women from Silsako came out to protest against the eviction drive, leading to clashes with police. The protesters then stripped down to their undergarments while sloganeering against the authorities.

Ribha Deori, from the Deori tribe, was one of the two women who protested half-naked, opposing the eviction drive.

Deori said her family bought nearly 3,600 sq ft of land from another tribal landowner in 2004 along the Swargadeo Rudra Singha Path, a major road near the Silsako wetland.

Deori said she bought a piece of land that farmers no longer cultivated. Instead, the Guwahati Municipal Corporation dumped waste there, and it wasn’t a pristine lakeside.

By 2020, Deori said, the area was relatively developed.

They had paved roads to the neighbourhood, electricity connections, GMC’s holding number [a number given to identify properties], and their regular taxes to the administration, which provided legitimacy to the houses they constructed.

Still, the house she constructed during the Covid-19 pandemic restriction was reduced to rubble.

“They brought the Act in 2008, but people have lived here for decades, much before the Act was introduced. If the land rights of these people are not secured, then what’s the deal here?” she said.

(Mahmodul Hassan is a journalist who writes on human rights, social justice, and policy issues. He is a contributing researcher with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers studying land conflicts, climate change, and natural resource governance in India.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.