Updated: May 7

New Delhi: “It (oxygen) will come in 2 days.”

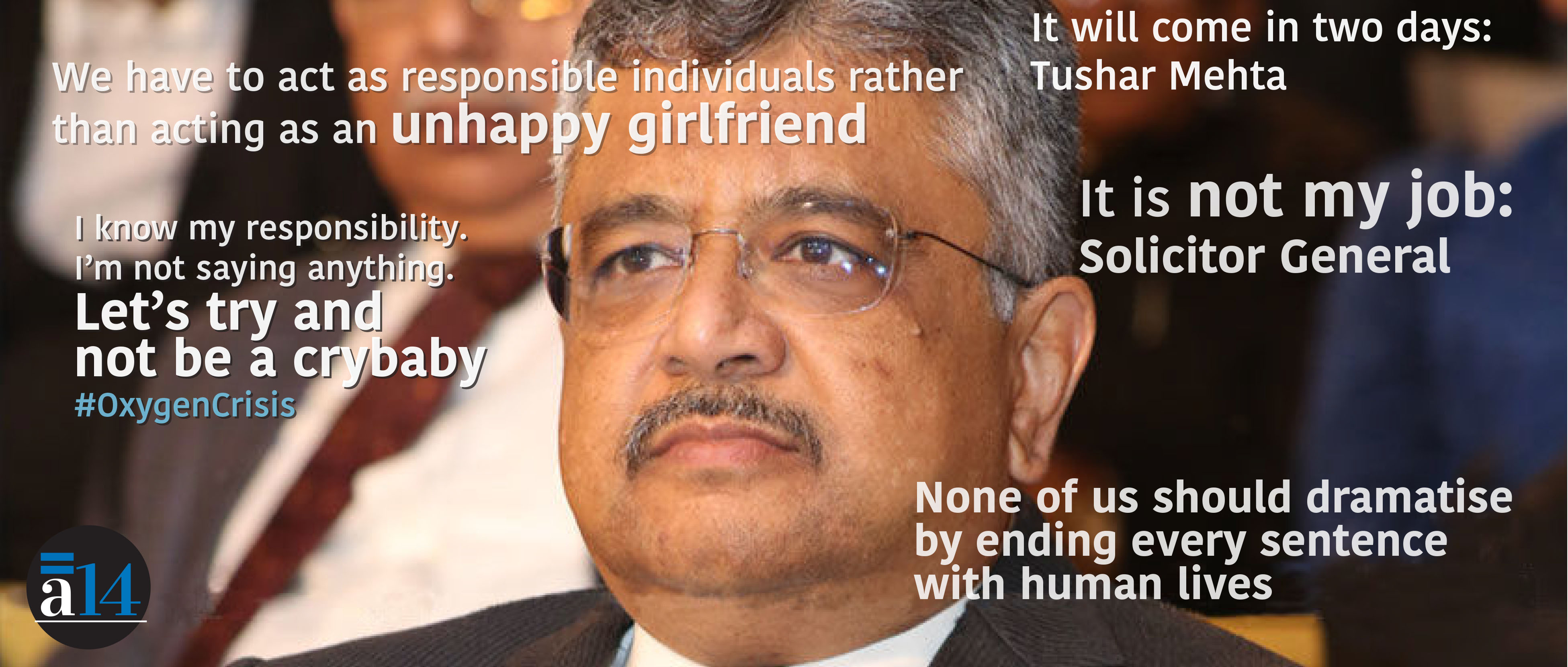

“We have to act as responsible individuals rather than acting as (sic) an unhappy girlfriend.”

“Let’s try and not be a cry baby.”

“It is not my job.”

"None of us should dramatise (matters) by ending every sentence with human lives."

Through its solicitor general, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, over nine days to 27 April 2021, offered a series of misrepresentations or seemed incapable of answering queries put to it in by a Delhi High Court division bench of Justices Vipin Sanghi and Rekha Palli, hearing urgent petitions from seven Delhi hospitals pleading for oxygen.

The court case unfolded as hospitals, clinics and nursing homes struggled to keep oxygen flowing through their pipelines during a deadly second wave of Covid-19 infections, which has claimed 15,000 lives in India’s capital over the last year.

Solicitor general Tushar Mehta refused to accept 21 people died of oxygen shortages in Delhi; refused to accept the Centre had any role to play in those shortages; could not explain why the Centre was unable to deliver oxygen that it promised in court; and said it was not the Centre’s job to reallocate oxygen.

Aside from the obfuscations and denials, the solicitor general’s widely circulated statements on these issues struck a particularly discordant note with angry and desperate patients and doctors.

While Mehta stalled the court and Justices Sanghi and Palli made strong remarks (here and here) about the Centre’s approach to oxygen supply, it also criticised the Delhi government for failing to distribute oxygen to hospitals, clinics and nursing homes.

“Set your house in order. Enough is enough,” the Court told Delhi government counsel Rahul Mehra on 27 April. “If you cannot manage it, tell us, then we will ask the central government to send their officers in and do it. We will ask them to take over. We cannot let people die like this.”

On 27 April, after nine days of hearings, the Delhi government told the High Court that oxygen supplies were now “healthy”, but doctors and hospitals reported otherwise (here and here), and shortages and erratic oxygen supplies continued, according to our review of court orders, conversations with hospitals and government officials.

We examine the case through five statements that Mehta made to Delhi High Court:

ONE: 21 April 2021

Mehta: ‘It [Oxygen] will come in two days’

Fresh cases: 24,638; Dead 249; Positivity rate 31.38 %

On 27 April, seven days had passed since Mehta said Delhi would receive 480 metric tonnes (MT) of Oxygen “within two days.”

Mehta told the court that the Centre’s responsibility was “only allocating” the oxygen. “Allotted quantity, increased to 480 MT, will reach Delhi,” he said. When Mehra, representing the government of chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, asked Mehta about a deadline, he made the promise of two days.

For that entire week, the supply of oxygen remained lower than 400 MT. It was on 26 April that 407 MT was delivered to Delhi. That shortage was borne out by New Delhi’s hospitals, who continued desperate appeals for help (here, here, and here)

Gautam Singh head of Shri Ram Singh Hospital and Heart Institute in East Delhi realised on 25 April how deadly this delay could be. Five days after the courtroom exchange, his 100-bed hospital was left with just two hours of oxygen.

Singh knew what this meant. Without oxygen support, in critical cases of Covid-19, death was inevitable. Half the beds at Shri Ram Hospital were reserved for Covid-19 patients; 36 patients were on oxygen beds, while 16 were in the intensive care unit with ventilator support.

Sensing the emergency, Sri Ram hospital sent its vehicles to all nearby oxygen plants as early as 4:30 am on 25 April. The hospital made desperate calls to people in Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh through the day. There was no oxygen to be found anywhere.

On 23 April, 25 Covid-19 patients died at one of the city’s best private healthcare facilities, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital. A few doctors said patients had died of suffocation, struggling for breath after oxygen ran out. On 24 April, 21 of the most critical patients at Jaipur Golden Hospital died in similar fashion.

As oxygen levels fell citywide, on 25 April Singh released an SOS video and sent it to everyone he knew. “It was a matter of do or die,” Singh told Article 14. “A tragedy was waiting for us.”

In his neat white coat over a white T-shirt, Singh pleaded: “We have young patients who will die in a matter of two hours. I request you, please send oxygen to us. We need oxygen for patients.”

Singh’s voice choked as he completed his sentence. “They will die. They need oxygen. We can save them."

After his SOS message, hospitals in east Delhi gave him two cylinders. Later Delhi police officials also helped refill oxygen cylinders, as did Tehseen Poonawalla, a social worker.

On the night of 27 April, Singh pleaded to Article 14: “I need 50 cylinders, and we are getting only 10 cylinders from our supplier. We have not slept for four days looking for oxygen everywhere. Please help us.”

TWO: 22 April 2021

Mehta: ‘We have to act as responsible individuals rather than acting as (sic) an unhappy girlfriend’

Fresh cases: 26169; Dead 306; Positivity rate, 36.24

Mehta made the “unhappy girlfriend" comment to the Court on a day when 26,000 new Covid-19 infections were recorded in Delhi and 306 died.

When Mehta made the comment, there were already more than 90,000 active cases in Delhi, and over the next week, that number was likely to exceed 100,000, with a peak positivity rate of over 36%, compared to 0.30% on 22 February 2021.

The Delhi government told the High Court that 20% of these active cases would require oxygen support.

Delhi asked the Centre for 700 MT; the centre increased its quota from 378 to 480 MT per day, which, as we said, has not arrived despite Mehta’s assurance to the Court.

Most patients with Covid-19 have a respiratory tract infection, and in the most severe cases symptoms can include shortness of breath. In a small proportion of such cases, this can progress to a more severe condition, called the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), where oxygen support is vital.

Currently, hospitals cannot cope with new patients or oxygen needs. In 2020, for instance, Shri Ram hospital reserved 25 of 100 beds for Covid-19 patients.

“However, this year, all of a sudden, the government asked us to reserve 50 beds,” said Singh. “I did not get the time to hire more staff or to supplement beds with oxygen support. With limited capacity, our caseload was increased by twice. On top of that, there is no oxygen. How will we treat our patients ?”

THREE: 24 April 2021

Mehta: ‘Let’s try and not be a cry baby’

Fresh cases : 26169; Dead: 306; Positivity rate 36.24

This was Mehta’s statement when the Delhi High Court told him that “citizens can't be allowed to die like this”. That was the day 21 patients died at Jaipur Golden hospital.

Ajay Bedi, a doctor at the East Delhi Medical Centre and secretary of the Delhi Medical Association Nursing Home Forum, told Article 14: "I have never felt as helpless as I feel right now."

At Bedi’s hospital, 40 beds needed 12-13 oxygen cylinders every day before the pandemic. Now, they need at least 60.

Bedi said hospitals regularly shared SOS on the nursing home forum, which he considered the “worst sufferers” of the oxygen shortage.

“Whenever oxygen tankers arrive, the priority is government hospitals, and private hospitals with over 100 beds are refilled next,” said Bedi.

“Whatever is left reaches a small private hospital like ours last."

Bedi said many doctors were “running pillar to post to get oxygen”.

“The situation in hospitals is also a reason that many people are opting for treatment at home,” said Bedi. “That, in turn, is creating more demand for oxygen cylinders.”

The “cry baby” comment did not go down well with Kuldeep Kumar Pandey, 30, who could not stop coughing when we spoke to him. Pandey tested positive for Covid-19 on 19 April and has been in home isolation since with his family in the north Delhi neighbourhood of Sant Nagar, Burari.

His oxygen level plummeted to 87 (anything below 94 is cause for worry) on 21 April.

“Somehow we arranged an oxygen cylinder the next day,” said Pandey, an editorial assistant at a Hindi university. “Now, for the last two days I am looking for a refill, but there is no oxygen. My mother is also (Covid-19) positive with an oxygen level of 83.”

“The government should at least accept its own mistakes and pay attention towards basic healthcare facilities,” said Pandey. “People are dying of Coronavirus and the government is playing with peoples’ life for its own political gains.”

“I just need an oxygen cylinder,” added Pandey.

FOUR: 26 April 2021

Mehta: ‘It is not my job (to reallocate oxygen to Delhi)’

Fresh cases: 20201; Dead, 380; Positivity rate, 35.02 %

Until 26 April 2021, despite the Centre's allotment, 480 MT of oxygen had not reached Delhi.

Delhi does not have its own oxygen plants. Out of its 480 MT oxygen, around 100 MT of oxygen comes from plants in West Bengal and Orissa, more than a 1,000 km to the east.

“The Centre decides the companies from which we get oxygen. The revised quota that the Centre has allotted to us, a substantial part of it, is to come from Odisha,” said Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal on 23 April. “But it will take several days to bring oxygen from Odisha to Delhi by road.”

Aside from the distance, the shortage of special cryogenic tankers to store liquid oxygen and cylinders make transportation of oxygen more difficult. A few empty cryogenic takers were airlifted to West Bengal and Orissa, after which full tankers returned to Delhi on special trains with 70 MT of Oxygen on 27 April 2020.

“The shortage of cylinders and tankers is so grave that currently my oxygen supplier has given me cylinders on rent,” said Singh. “The plants are creating oxygen but there is no way of transporting that gas without cylinders.”

Many hospitals told us that confusion continued because no one was clear how and when the oxygen would get to them.

“We are not in touch with the Centre,” said Bedi. “For us, the Delhi government is the boss. But the nodal officers appointed by Delhi are not responsive. Everyone in the Delhi secretariat knows our critical condition, yet they choose to work at a snail’s pace.”

The Delhi High Court on 27 April 2021 also told the Delhi government that it cannot fight the “war” against the Covid-19 pandemic by issuing “unreasonable orders” to the hospitals, adding that it appeared officials were out of sync with reality.

“You are completely out of sync and you do not know what the ground reality is. You do not know how hospitals are coping up with the situation. What is the inflow of people, shortage of oxygen and medicine, doctors and paramedics. Why do you come up with these orders? We do not understand,” told the court to Delhi government.

Explaining their night of death, advocate Sachin Dutta, representing Jaipur Golden Hospital, told the Court that by 23 April 2021 the hospital was supposed to get oxygen supplies by 5 pm, but those reached only by midnight.

“No one responded to our calls,” Dutta said. After the hospital issued multiple SOS messages, some oxygen was diverted from the government-run All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi’s premier hospital. “It was about 10-15 minutes late; 10-15 minutes cost 21 lives, 21 families.”

The Delhi government told the court if the state had sufficient medical oxygen, there would be few problems.

India’s medical-oxygen production is limited to about 8,000 MT per day, with a buffer of 50,000 MT. Oxygen demands have skyrocketed during the second wave of Covid-19, not just in Delhi but across most north Indian states. India’s oxygen exports rose to over 700 % in January 2021. Of 162 oxygen plants tendered in October 2020, only 33 are working, revealed an investigation by Scroll.in.

Rajya Sabha member of Parliament Jairam Ramesh of the Congress party and a member of a parliamentary standing committee on health tweeted that on 21 November 2020 the committee had recommended the government “encourage adequate production of oxygen.”

A senior Delhi government official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said: “No one was prepared. Neither Centre nor the state.”

“The Delhi government is struggling right now to manage oxygen demand and supply,” the official said. The Centre has said that we have allocated 480 MT of oxygen, now you go and procure (it) yourself.”

“On the one hand, states like Haryana block the tankers, on the other, tankers need at least 24 hours to reach Delhi (from West Bengal and Orissa),” said the official.

“On top of that there is a shortage of tankers and cylinders. Hospitals are giving us SOS calls. Who all (sic) will we handle?”

The High Court had asked the Centre to rework allocations, so that Delhi could get its quota; 21 lives had been lost, the judges said, to which Mehta replied that it was “not because of non-supply by me (the Centre)”.

When the court told Mehta that it was the Centre's job to ensure supply, Mehta asked Delhi to put its own system in place.

The Court told Mehta: “The same can be said about you.”

FIVE: April 26 2020

Mehta: ‘None of us should dramatise (matters) by ending every sentence with human lives.’

Fresh cases: 20,201; Dead: 380; Positivity rate: 35.02 %

Ajay Koli, 38, an academic researcher, lost his father to Covid-19 on 24 April. He spoke to us on 25 April while on his return from Uttar Pradesh after immersing the ashes of his father.

Koli’s mother, also Covid-19 positive, was under home isolation with low oxygen levels. He pleaded for oxygen in an SOS: “I don't want to lose my mom now.”

"Many people are saying their loved ones goodbye before their death,” Koli told Article 14. “In my street, four people died the same day my father passed away."

On the morning of 27 April, Pandey got some leads on oxygen in Faridabad, Haryana. “Around 2 pm, district officials came and dispersed us,” he said. “They said that oxygen was only for hospitals and ambulances.”

He pleaded for oxygen: “Madam, kuch hua kya oxygen ka? Madam, did you find any oxygen?” At the time of publication, this reporter was still trying to find an oxygen cylinder.

Koli did not find oxygen for his mother, three days after his father’s death. “There is a mad rush for oxygen and prices are at an all-time high,” said Koli.

Commenting on Mehta’s statements, Koli, a Dalit, said he was “shattered” by the Centre’s apathy. “Lives do not matter for this government,” said Koli. “Our lives matter the least.”

(Srishti Jaswal is an independent journalist associated with Reporters’ Collective. She is an NFI grantee and mobile journalism fellow with Internews.)