Bengaluru: Between July 2022 and May 2025, a cycle of revenge in southern coastal Karnataka claimed six lives—two Hindu and four Muslim.

The difference was how the state viewed the crimes.

The police registered the deaths of the four Muslim men as murder cases. In contrast, the two Hindu murders were registered under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967 (UAPA), India’s anti-terror law.

The cycle of vengeance started on 21 July 2022, when eight men from the Bajrang Dal reportedly attacked 19-year-old Mohammed B Masood following an altercation over the latter’s purchase of a calf.

A week later, just 5 km away, Praveen Nettaru, a 32-year-old Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) worker, was hacked to death, reportedly as revenge, by members of the Islamic right-wing organisation Popular Front of India.

Two days later, members of Hindu fundamentalist groups hacked down Mohammed Fazil, a 23-year-old daily wage worker outside Mangaluru city, seemingly to avenge Nettaru’s murder.

The trail of blood resumed on 1 May 2025, when Suhas Shetty, who was the prime accused in the murder of Fazil, was killed in an attack reportedly orchestrated by Fazil’s family.

On 27 May 2025, Abdul Rehiman, a local mosque committee member, was hacked to death with machetes by those who invoked Shetty’s name.

The terror law—committing a terror attack, conspiracy and membership in a terrorist group—was invoked only in the murders of Nettaru and Shetty.

In the Nettaru case, the National Investigative Agency (NIA) arrested 21 persons. None have received bail so far. Five of the accused in Fazil’s murder, including Shetty, were granted bail within 1.5 years.

The reason for the differentiated investigation seems apparent: unlike a murder charge, it is nearly impossible to secure bail in lower courts when facing UAPA charges.

Instead of investigations by local police, UAPA cases are investigated by the NIA, a counter-terrorism agency under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA).

The BJP, which has been in power at the Centre since 2014, and in Karnataka for 10.5 years over the past two decades, has been vocal about its penchant for the terror law. In November 2024, Union Home Minister Amit Shah told local police in states to use UAPA without “hesitation and as required”.

In the run-up to the 2023 elections, Prime Minister Narendra Modi touted the BJP’s use of UAPA: "In Karnataka, you have seen how Congress is encouraging terrorism. Congress had left Karnataka to the mercy of terrorists. It is the BJP that broke the back of the terrorists and has ended the game of appeasement.”

UAPA Weaponised Against Muslims

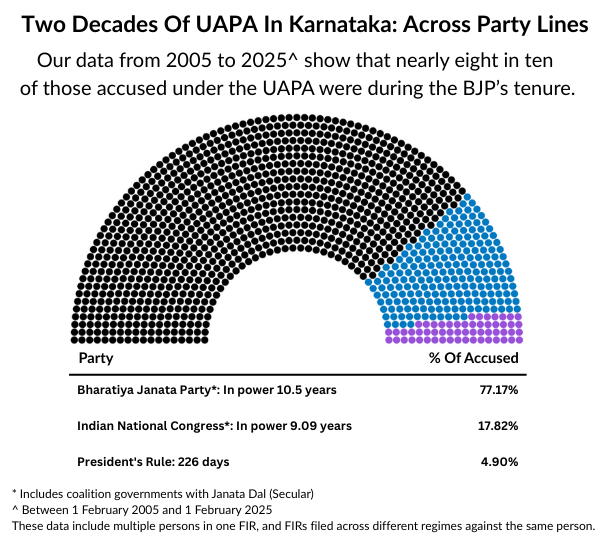

The first of this four-part series reported that incidents in which UAPA has been invoked from January 2005 to February 2025 in Karnataka, researched by the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London, revealed a stark bias in the application of the law by the BJP against Muslims.

Karnataka has seen nearly equal periods of rule by the Indian National Congress (INC) (9.09 years) and the BJP (10.5 years), and President’s Rule for 226 days. The Janata Dal (Secular) was in coalition with both parties periodically in these 20 years.

The data showed that eight in ten persons accused under the UAPA were during the BJP’s tenure. In other words, the BJP invoked the law 5.2 times more than the Congress Party in Karnataka over the past twenty years.

Of the 925, 783 (84.6%) were Muslim.

688 (87.8%) of the 783 Muslims were accused under the BJP, compared to 95 (12.13)% under the Congress.

In the first part of this series, we described how communal and partisan incidents accounted for 56.1% of all UAPA cases over 20 years. Here, persons are accused of spreading hatred among communities regardless of the religious identity of the perpetrator. In Karnataka, this included charging people under the UAPA for participating in protests, making hateful speeches, assaults on or murders of RSS/BJP activists, distributing pamphlets, or affixing posters.

This also includes an incident in 2012, where nearly 40 members of the Hindu Jagran Vedike were accused under the UAPA, along with other penal offences, for assaulting men and women at a homestay in Mangalore. Charges under UAPA were dropped, but the trial proceeded under other laws. In 2024, all the accused were acquitted.

Under the BJP, 70% of people accused under the UAPA were accused of inciting hatred. In contrast, under INC governments in Karnataka, communal/partisan incidents formed just 11.8% of all UAPA arrests.

In Part 2 of this series, our data show how the UAPA is used seemingly to prevent the spread of hate, but in fact been used largely against Muslims, particularly under the BJP.

This law is used increasingly as a replacement for ordinary crimes, with governments across party lines having used it as a tool for appeasement or even treating the murders of BJP or RSS activists as a matter of national security. During the BJP’s tenure in Karnataka between 2019 and 2023—out of the 925 persons accused, 529 were during this tenure—where it was invoked after protests, communal riots and even speeches.

During this period, then Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai had openly advocated the use of UAPA in communal conflict.

“There seems to be no check in terms of what constitutes matters of national security and the filing of UAPA charges,” said Mayur Suresh, reader in law at SOAS and the principal investigator on this UAPA data series.

“Do murders, assaults, or protestors blocking a road constitute national security?” said Suresh. “Unfortunately, it is left to the home ministry to decide without oversight.”

In an attempt to murder case that was converted into a terror case long after the first information report (FIR), while to the four main accused in July 2020, a judge in the Karnataka High Court observed: "There is total ambiguity in the object and purpose of the alleged conspiracy...The argument (filing of UAPA charges) appears to have been advanced without any supporting material, obviously with a view to frustrate the right of the petitioners to bail..."

Across the country, state police in BJP-governed states have used UAPA charges for protests and riots frequently.

UAPA has been used in Delhi 2020 riots, where Muslims were disproportionately the victims; in Tripura, the BJP-led government used the charge not against right-wing organisations that rioted in 2021, but against an independent fact-finding group that had documented the destruction of mosques and Muslim-owned properties; in Haryana, UAPA was invoked against a Muslim MLA six months after the July 2023 violence in Nuh. In Assam, the BJP government charged opposition MLAs with UAPA after the 2020 anti-CAA protests, while Maharashtra police targeted human rights activists after the 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence.

“UAPA is a tool that is inherently political,” said Radhika Chitkara, an assistant professor (law) at NLSIU, Bengaluru, whose research specialises in the use of the UAPA.

“Whether a violent incident has taken place or not is immaterial. It gives the discretion to the state to decide on what they consider a threat, or what kind of political formations are allowed or can be banned under the law,” said Chitkara. “In effect, it allows the government to determine the space given to a political activity.”

When Murder Becomes A Terror Plot

The politics over murders is enmeshed in Karnataka’s recent political history.

Between 2016 and 2023, the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB’s) Crime in India publications recorded 53 murders attributed to communal or political reasons in the state.

INC was in power from 2016–2018, followed by the INC–JD(S) coalition from 2018–2019, and then the BJP from 2019–2023.

In five instances (excluding the murder of Suhas Shetty, which occurred after the conclusion of the study), UAPA was invoked. All involved the murder of members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—a pan-Indian right-wing Hindu nationalist organisation—its affiliates, or BJP functionaries.

In Karnataka, the earliest instance was the murder of R Rudresh, an RSS member, in Bengaluru in 2016. According to the FIR, on 16 October, Rudresh was attacked by men on a motorbike after an RSS rally. Rudresh was in the RSS uniform—white shirt and khaki shorts—and was struck on the neck with a machete. He bled to death before he could be taken to the hospital.

The police filed a case under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) sections for murder and conspiracy. Five persons were arrested, all from the Popular Front of India (PFI), an Islamist organisation, banned and designated an unlawful organisation under the UAPA by the Modi government in 2022.

BJP, which was in the opposition, had termed the murder a “terror act” and ramped up the political pressure.

Three weeks later, the police invoked sections of UAPA, claiming that the accused made phone calls to “various organisations” in the country, which “pointed out a deep conspiracy that had a direct bearing in causing harm to the integrity of the nation.” This was reportedly done to deny bail to the five arrested.

On 7 December 2016, the MHA suo motu transferred the case to NIA.

Four months later, a Karnataka High Court judge, who was hearing a petition filed by the accused against the takeover, quashed the NIA investigation. The order said the murder was an “ordinary criminal activity” which “cannot be classified (as intending) to strike terror in the minds of the general public”.

A year later, this order was set aside by a two-judge bench as being “judicial over-reach” and being “unsustainable in law”.

“What is in the interest of national security is not a question of law. It is a matter of policy,” said the order that reinforced the MHA’s authority to decide on investigations into incidents of national security.

Under the NIA, the investigation doubled down on the terror angle. The chargesheet stated that the “killing of RSS workers would immediately strike terror in a section of people and prevent many of them from joining the organisation.”

While the police had accused five of the murder, the NIA chargesheet listed a sixth accused, Mohammad Ghouse Niyazi, a local functionary of the Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI), the political wing of PFI, who reportedly fled to Tanzania soon after the murder. The NIA claimed he had indoctrinated the accused and persuaded them to “believe that the fight against the RSS was a ‘holy war’”.

Niyazi was arrested on 2 March 2024 upon his return to India.

Three months later, he turned approver for the NIA. Niyazi has since testified to participating in PFI indoctrination camps against the BJP and RSS, and even witnessed the conspiracy to murder.

Almost immediately, Niyazi was granted a pardon. The other accused have called him an “NIA plant” in unsuccessful applications seeking revocation of his pardon.

The punitive power of a UAPA charge is evident. Less than half the 125 witnesses have been heard in the NIA special court in Bengaluru.

The five arrested have been in prison for eight years now, denied bail by the trial court and the Karnataka High Court.

In contrast, eight persons reportedly belonging to Hindu radical organisations accused of assassinating writer and journalist Gauri Lankesh in 2017, were released after six years on bail on a murder charge.

UAPA As A Way To Temper Discontent

After the BJP came to power in mid-2019, invoking UAPA became a way to soothe discontent among the rank-and-file after the murder of its workers.

On 20 February 2022, Harsha alias “Hindu Harsha”, a Bajrang Dal activist against whom “Muslim youths had developed animosity” due to his “Hindutva work”, was stabbed to death by “Muslim miscreants”, the FIR said.

Ten people were arrested by the local police, who said the victim and the main accused had an altercation six months before the murder.

However, in the town, right-wing groups amped up their protests, seeking a terror probe. A month later, the ruling BJP government transferred the investigation to the NIA.

Of the ten accused, two accused of harbouring the others have been granted bail. The rest, who were accused of being members of an unspecified “terrorist gang” that conspired to kill a “prominent Hindu leader” to “terrorise people of Hindu community”, are still in jail.

UAPA For Hundreds Of Muslim Protestors

Between 2020 and 2022, the NCRB notes there were at least 38 incidents of communal riots and 51 riots that resulted in injuries to police personnel or government officials in Karnataka.

UAPA was filed by the BJP government in three cases: all involving Muslims protesting alleged police inaction against social media posts that were “derogatory” to Islam.

Over 400 people were cumulatively arrested under the law, and many have spent at least five years in prison without bail.

On 11 August 2020, a mob surrounded the DJ Halli and KJ Halli police stations in central Bengaluru. The crowd had demanded action against the relative of a local politician who had reportedly posted a derogatory Facebook post about Prophet Mohammad.

Scores of vehicles were set ablaze, and the houses of the politician and his relative were attacked. Nine people were injured. Four Muslims among the crowd were killed in police firing.

Muzammil Pasha, the Bengaluru district secretary of SDPI, was at the police station throughout the evening of the violence. He claims that the police had called him there, along with local political and religious leaders, to pacify the crowd. He was among those who unsuccessfully beseeched the crowd to disperse.

When the crowd surrounded the police station, threatening to burn it down, Pasha claimed to have helped protect and evacuate the police.

Later that night, much after the crowd had dispersed, he was called again to the police station. This time, he saw BJP ministers talking to television reporters there. They had called the violence a pre-planned conspiracy by SDPI and PFI.

“I knew then that they would do what they did in the Delhi riots. That UAPA will be enforced against us,” Pasha told Article 14 in an interview at the SDPI office close to the place where the riots took place.

The aftermath of the riot was swift: 246 people were chargesheeted for the two riots, including 47 under UAPA. Pasha was accused 1 in the violence that took place at the DJ Halli police station and accused 2 in the violence in front of KG Halli police station.

“At the police station, I had told the crowd that anyone who intentionally insults the prophet will be hit by the policeman’s boot. It’s a phrase that came to me at the moment because I felt it was important to show the crowd that the police were with us,” said Pasha. “But, in the chargesheet, the police alleged that I told the crowd to hit the police with their boots. This is how they built the case against me.”

The NIA took over the cases nearly 1.5 months later.

Six months later, terror charges were dropped against all but 47 alleged members of the PFI and SDPI in the two cases.

Pasha, who was among the first to be arrested, was granted default bail (a process in which bail is granted due to a delay in filing the chargesheet beyond the stipulated 180 days for a UAPA charge). But 39 persons charged under UAPA remain in jail.

“The police claim that it is a big SDPI-PFI conspiracy. But just four people arrested are actually members of SDPI,” Pasha claimed.

In multiple bail applications, the accused have argued that the case does not attract UAPA as it is “a simple case of rioting”.

However, despite this argument that riots do not rise to the level of a national security problem. The judge reasoned that the mob intended to strike terror by failing to assemble peacefully.

UAPA For Appeasement

The use of UAPA against protests was seen again on 16 April 2022.

154 people were arrested in Hubballi in central Karnataka after a violent protest precipitated by a WhatsApp status of a saffron flag over the Muslim holy site of Mecca.

Ten police vehicles were damaged, while nearly a dozen policemen were injured.

X’s recollection of the incident mirrors Pasha's experience.

X, a socio-religious leader who spoke to Article 14 on the condition of anonymity, said he had been called by the police to address an angry crowd that had gathered by the station. By the end of the night, he was arrested.

Of the 12 cases filed in the aftermath of the riots, the state police applied for UAPA in four.

X was whisked away to the Central Jail in Kalaburagi, some 330 km away from his home. “I was not interrogated. No one even told me what the allegations against me were,” said X, who is in his 50s. “We got to know it was a terror charge only when our bail was rejected. On television, the police commissioner appeared, saying it was a terror case.”

This time, the chargesheet alleged that the offending messages were circulated in three WhatsApp groups, which, the police said, attracted provisions under UAPA for “terror association”.

The political nature of the case became a rallying point in the 2023 elections in the constituency. When the Congress came to power in Karnataka, it withdrew the four cases.

Local police were conducting the investigation into the Hubballi riots, and the cabinet had the authority to do so; while the NIA was investigating the two Bengaluru riots cases, the state could not withdraw these cases.

The BJP termed the decision to withdraw the four UAPA cases “minority appeasement”.

For X, it doesn’t feel like a relief. “I’m just scared. If I’m out of the house for more than an hour, my family calls. We must have spent Rs. 20 lakh on the case (lawyers, travel, loss of income).

“My family sold two plots of land. We sold our gold,” he said. “All of this because one vehicle got overturned?”

Second of a four-part series. Read Part I here, Part III here and Part IV here.

Names of those interviewed have been withheld on request.

Credits:

Investigative reportage, data mining, research & analysis for Karnataka, Mohit Rao; All India data mining and analysis, Sakshi R., Nikita B; Research on acquittals in UAPA in Karnataka, Zeba Sikora; Background research, Vibha S.; Research Direction, Lubhyathi Rangarajan; Principal Investigator, UAPA Data Series, Mayur Suresh; Edited by: Betwa Sharma.

This data is produced by a research project at SOAS, University of London, funded by the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.