Bandipora, Jammu and Kashmir: For two years, Roshan Jan, a 57-year-old woman from Quil Mukaam in Bandipora district, North Kashmir, has battled not only late-stage 3 ovarian cancer but also a system that promised to protect her family and millions of others across India from debt.

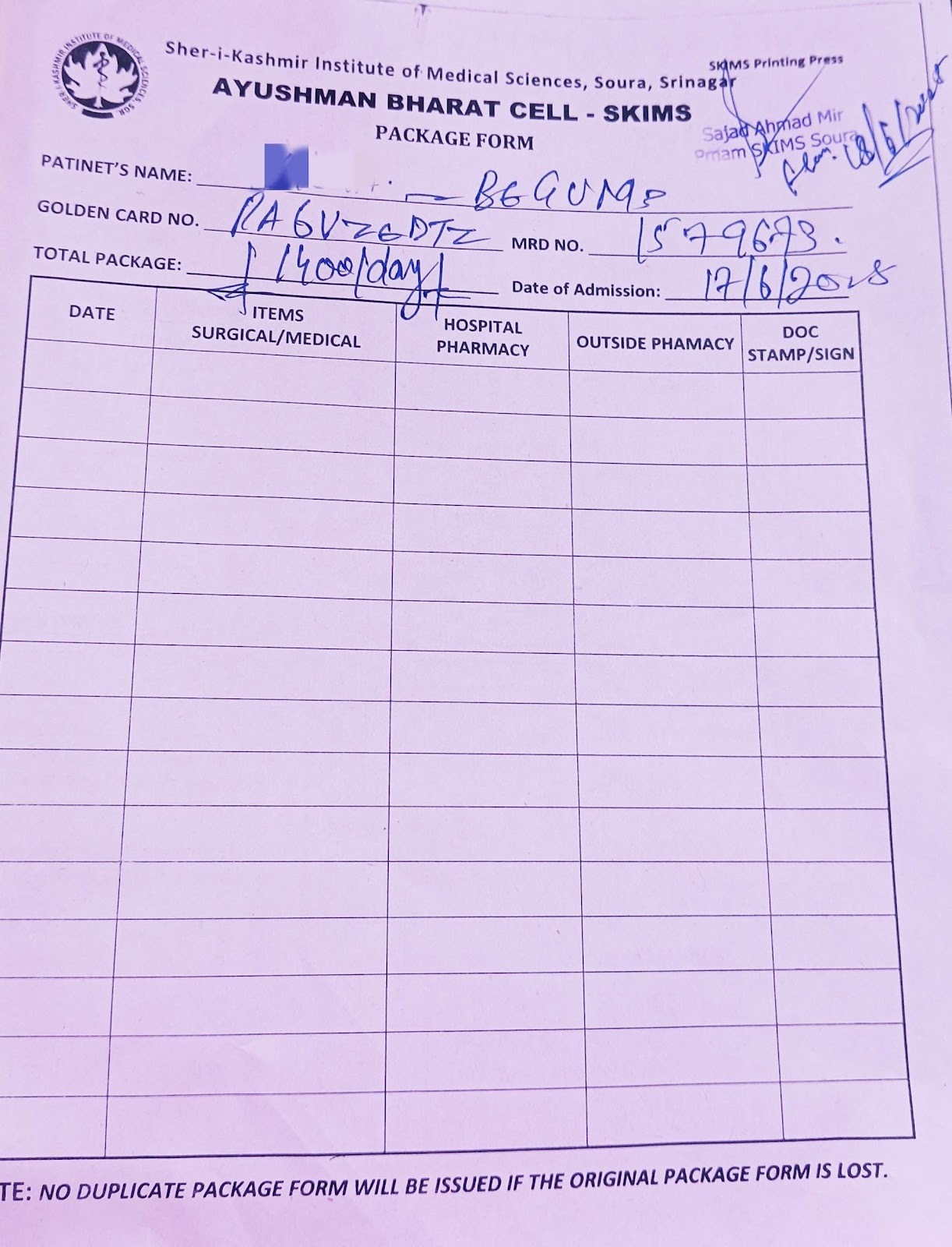

The “Golden Card”—colloquial for her Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) insurance card—should have made treatment and medicines free at government and private hospitals. Instead, the Jan family, like many in Kashmir and beyond, find themselves pushed to the edge by mounting out-of-pocket expenses.

"I am shocked and disappointed that the scheme hasn't helped us financially," said Roshan Jan, her voice strained from exhaustion and treatment.

Her cancer has spread beyond the ovaries but not to distant organs, yet, so treatment is typically aggressive—involving surgery and multiple rounds of chemotherapy—and recovery is challenging.

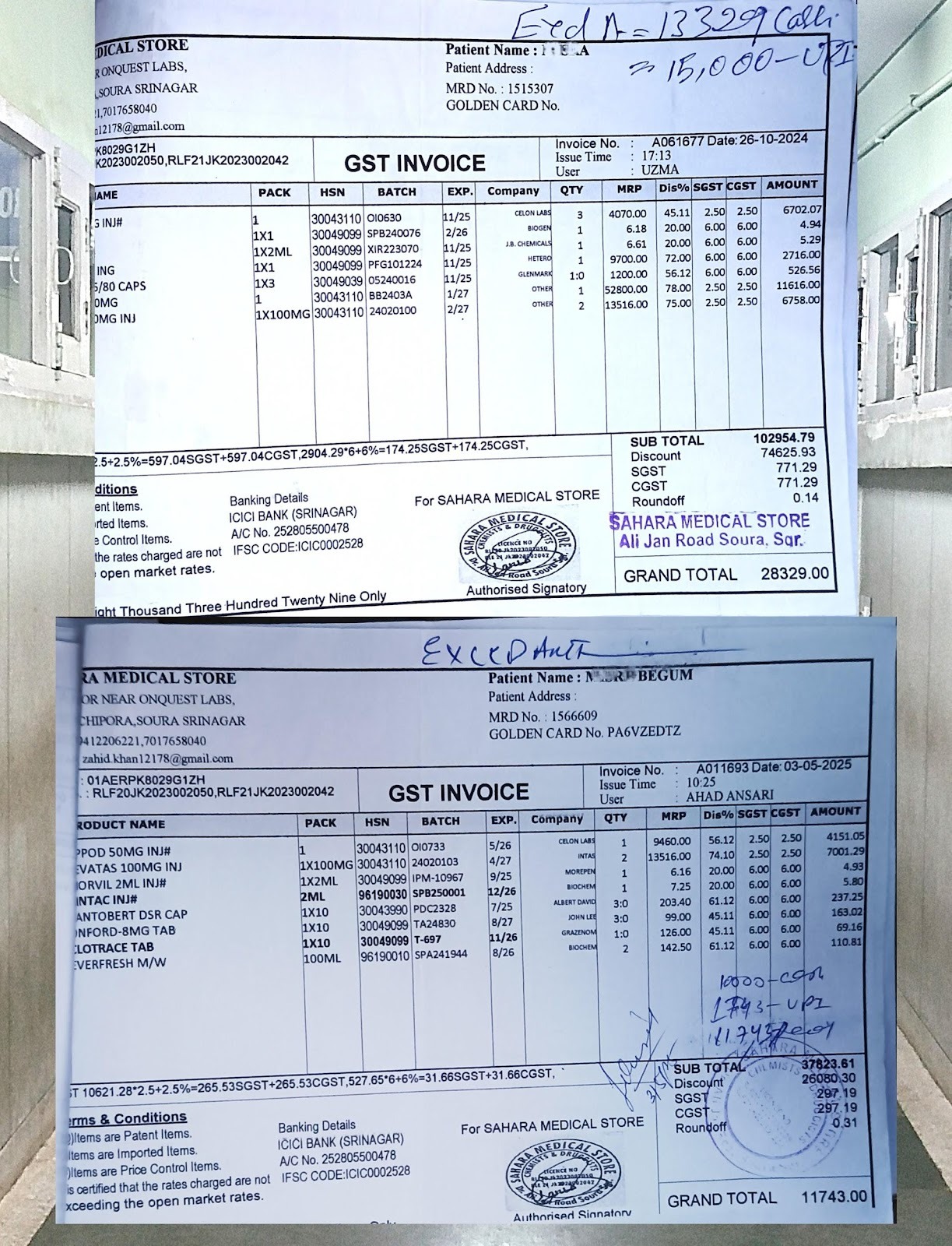

"Each chemotherapy cycle costs us Rs 25,000, and regular tests add another Rs 10,000 to the bill,” said Roshan Jan. “It's a huge burden on my family."

Her Golden Card, issued based on the Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC) 2011, is meant to guarantee up to Rs 500,000 a year in hospital care. In practice, she and her family are left with a pile of bills.

Her husband is a labourer, earning Rs 400 a day at the best of times. As his daily wages shrank—for days missed at the brick kiln or construction site to care for Roshan Jan—the finances of the Jan family crumbled.

Selling Assets

Their daughter, only in Class 10, began missing school more often, helping to carry Roshan through Srinagar’s hospital corridors. Their son Naveed Ahmad, 25, searches for odd jobs but often returns empty-handed.

Neighbours in Quill Mukam describe how the family has borrowed from relatives, sold jewellery, and mortgaged a parcel of land.

At Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS) Soura in Srinagar, Roshan Jan had checked into the day-care chemotherapy ward. More than a dozen other women, most clutching Golden Cards, waited in queues outside the pharmacy.

Here, Roshan was told again that the “key drugs” were not available under PM-JAY rules unless she was admitted overnight.

“When we undergo chemotherapy, it takes up an entire day at the hospital,” Roshan explained. “They say only those who stay the night get their medicines. My treatments are always day care. Every new test, it's another bill. We have nothing left.”

The nodal officer at SKIMS Soura, Dr Haroon Rasheed, refused to comment, saying he and other officials could not speak to the media.

Roshan’s family keeps every hospital slip and prescription. OPD cards are worn thin.

“I have asked the officials many times why the medicines are not covered—every official just says, ‘It depends on the file’,” said Naveed, shuffling through paperwork in their small living room. “It’s so difficult to understand what is included, but every week, we must pay.”

Ayushman Bharat: Promise & Reality

The Golden Card was the centrepiece of speeches and banners as a key to unlocking universal, cashless care.

Unveiled on 15 August 2018 in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Independence Day speech and officially launched in Ranchi on 23 September 2018, PM-JAY was touted as “the world’s largest government health insurance scheme”.

Modi promised it would give 100 to 120 million families—about 40% of the Indian population—up to Rs 500,000 per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation, and “free the poor from the burden of illness and debt.”

According to official statistics, those promises have been fulfilled in part: more than 404 million cards had been issued by March 2025, covering 147 million families, identifying recipients by census data, state lists, and all seniors above 70 as of 2024.

Yet ground reporting from Kashmir—and national audits—suggests a different reality.

A review published in March 2025 in a major health journal found “inconsistent enforcement and opaque priorities mean that coverage rarely reaches the sickest, and household health costs are not eliminated in practice”.

An August 2024 report from the think tank PRS Legislative Research found that between 2019-20 to 2022-23, 69% of allocated funds were used: despite a Rs 9,406 crore allocation for 2025-26, major services such as outpatient care and high-cost chronic treatments remain excluded.

In February 2025, Article 14 reported how delayed reimbursement and disputes over treatment costs have impaired Ayushman Bharat, with rising demand not matching its claims.

With an average claim settlement of less than Rs 10,000 from 30 million payments over five years, the promise of Rs 500,000 coverage for about half a billion people appeared unrealistic, we reported.

Crowded Corridors, Uncertain Benefits

Inside SKIMS Soura, we found corridors lined with families who traveled hours for treatment.

At the oncology registration counter, Jamsheda Mohammad, 23, from Agar village, Bandipora, sat beside her mother. The family spent nine months and between Rs 10,000 to Rs 20,000 on medicines alone—medicines they believed the Golden Card would cover.

“They say the family's limit is reached, but how can it be, when there is supposed to be Rs 5 lakh for each of us?” asked her mother. Jamsheda’s father is now bedridden; her mother survives on infrequent cleaning jobs.

A doctor at SKIMS, speaking on condition of anonymity, said: “Our biggest issue isn’t lack of cards—it’s that chronic patients come with PM-JAY cards thinking all is free, but get almost no high-value medicines. The most expensive therapies are outside the present scheme list. We see the frustration every day.”

Some of the therapies that patients told Article 14 they paid for include Cizumab 400, which costs about Rs 11,600 per dose after discount, to be used in conjunction with chemotherapy to treat a variety of advanced or metastatic tumours; Bevatas, which comes in many doses, is used to treat brain tumours, ovarian, cervical and other cancers, can cost more than Rs 16,000 for every cycle after discount; and a nutritional support drug called Reomix Peri-1100 that can cost up to Rs 5,700 and provides important amino acids, glucose and omega-3 triglycerides.

In other city hospitals of Kashmir , queues are similar. Irfan Ahmad, a retired teacher, brings his wife for repeat cancer tests.

“We get advice, maybe a Ayushman Bharat dispensed supplement, but not free medicines or scans,” said Ahmad. “At the pharmacy, most medicines are ‘not available’; they tell us to buy from outside.” Each month they spend more than Rs 5,000 on medicines—over half their pension.

The paperwork is labyrinthine. Many Golden Card holders do not realise they must renew their cards annually, navigating poor internet connectivity and changing documentation.

“During COVID, everything moved online,” said a hospital receptionist, speaking on condition of anonymity since he was not authorised to speak to the media. “But villagers come for paper slips and don't understand that digital renewals must happen on time, or benefits may be suspended for months."

National Claims & Contradictory Outcomes

Authorities say Ayushman Bharat is transforming public health access nationwide. According to the union government, its health spending now covers nearly half of care costs.

Yet, independent reviews tell a different story.

A survey of low-income families in March 2024 from Bengaluru showed nearly half of Ayushman Bharat users sought loans from moneylenders at usurious interest rates for hospital charges—the average hospitalisation cost Rs 79,000, for which they received less than Rs 10,000 under the scheme.

Field surveys in Uttar Pradesh (January 2025) and Tamil Nadu (April 2021) place true awareness or use rates often below 20%.

Complaint data bear out these problems: more than 110,000 formal grievances were filed between 2018 and 2022, many from below-poverty-line families denied medicines or told their limits were exhausted long before the year was over.

In Kashmir, a January 2025 survey by the Rural Health Advocacy Group found only a third of eligible Golden Card users benefited yearly, and most still reported out-of-pocket costs above Rs 40,000.

System Delays & Overstretched Hospitals

Structural problems in PM-JAY led to waves of hospital suspensions across India in 2025. In August, more than 650 private hospitals in Haryana cut off Golden Card services, citing Rs 500 crore in unpaid government dues—a disruption replicated elsewhere.

In Kashmir, doctors report Rs 350 crore is owed to local facilities, with the result that hospitals ration treatments or send patients to private labs, where Golden Card coverage does not apply.

“Delays in payment affect everything,” said an administrator at SKIMS, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue.

“We are always behind in ordering drugs or paying our suppliers. For patients, medicines run out or are not available, and staff face pressure from both sides.”

Patients said they faced a tortuous verification process with every visit. “Half the time, the numbers don’t match the hospital computer with the main database,” said Naveed Ahmad. “We are always told to come back in a week.”

Fraud, Cutbacks & Shrinking Inclusion

In rural Kashmir hospitals, nurses and clerks often explain to families that only some drugs and tests are included, and expensive injections, blood tests, or many scans must be paid for.

Fraud exacerbates coverage problems in the Prime Minister’s programme.

In November 2025, the National Anti-Fraud Unit removed over 1,100 hospitals for fake or inflated billing and flagged more than 270,000 cases, worth Rs 562.4 crore, for further investigation.

At the same time, policy expansion to cover all senior citizens and the general population since September 2024 further stretched limited funds, often at the expense of Kashmir’s poorest.

Outreach workers in Bandipora and Baramulla said poor families are frequently told their “quota” for the year is exhausted by July.

In the OPD waiting area at SKIMS Soura, Abdul Rashid explained, “Every month we are told our next test or scan isn’t covered. The nurse says to check with the clerk, who refers us back to the desk. We go home and wait, repeating this for weeks.”

Inside Kashmir’s Hospitals

Shazia Akhtar, a cancer patient from Kupwara, has skipped her last chemotherapy cycle.

“My father sold his tools for the first chemo rounds, but now we just cannot pay for the key medicines,” she said. “The card is always shown but nothing is included. I have not got a single injection free.”

In Bandipora hospital, two sisters counted coins after another blood test for their mother: “Our BPL and Golden Card haven’t helped us,” said one. “We’re asked to go to private labs for every real investigation. For surgery, they said to come back with reports—costing more than Rs 10,000 each time.”

At the hospital’s Ayushman pharmacy, stocks of cheaper drugs are carefully watched, often exhausted by Wednesday.

Showkat Ahmad recalled, “One day I didn’t have enough for my mother’s medicine. A staff member said, ‘For Rs 9,000, I’ll get it quietly for you. But don’t tell anyone.’ We pressed, and the price fell to Rs 6,500—the same medicine we were told isn’t on the scheme. The main medicines are never given free, even after arguing.”

Nurses and clerks in public hospitals said there was little they could do: the online system reflects only small quantities of basic medicines; the rest are up to “management discretion” or hospital stock. In between, patients are left adrift.

Living With Uncertainty

In hospital corridors, rural waiting rooms, and village dispensaries across Bandipora, Baramulla, and beyond, families described cash-strapped realities: holding government cards, clutching bills for medicines, scans, and blood tests—many from private clinics outside the scheme.

Our reporting documented at least nine families in Bandipora who borrowed money or mortgaged valuables for treatment in the past year. Many encountered bureaucratic runarounds and unclear claim limits.

In conversations with social workers, doctors, and activists, the demand was the same: clarity, real support for chronic and catastrophic health needs, and consistent delivery in rural Kashmir.

Bisma, 21, waiting at her mother’s bedside in SKIMS’s medical emergency ward, summed up the frustration of many families.

“We hear that the scheme is the best in the world, so why can’t we get what we need in Kashmir?” she said. “The government says everything is available, but every day, my family pays more than it can afford.”

(Zaid Malik is an independent journalist who reports on healthcare, social justice,religion and the environment. He has worked with national and international outlets.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.