Mansa/ Patiala/ Sangrur: Gurjit Kaur, 32, who lives in Bajewala village of Mansa district’s Jhunir block, received only Rs 1,000 in February 2022 as wages for seven days of work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), 2005. “A few days’ wage gets deducted,” she said.

She could not understand how her wages were calculated for the work she did clearing shrubs from the sides of a highway. According to the state-wise daily wage rates fixed by the union government for the financial year 2021-22, workers under the workfare programme were to receive Rs 269 per day in Punjab. A rough calculation of Gurjit Kaur’s average daily wage for about 80 days of work she got in 2021-22 worked out to Rs 180 per day.

The MGNREGA gives every rural Indian household a legal entitlement to100 days of work every year, a rights-based welfare scheme operated with the aid of community-based accountability mechanisms at the level of gram panchayats, village-level elected bodies.

But Gurjit Kaur said she could not question the sarpanch, the chief of the village-level elected representatives, or ask him to help resolve the problem. “Or else I might not get the work,” she said.

By the third week of March 2022, average pay per day under MGNREGA in Punjab stood at Rs 263.16—Gurjit Kaur had received about 53% of the state average.

“I work to feed myself and the children,” said the mother of two. “Aise kaam karanda sanu ki fayda jab sahi dihadi nahi mildi? (What is the point of working so hard if I don’t get the wages I deserve?)”

In four villages across three districts that Article 14 visited, all of them in the Malwa region of southern Punjab, there were dozens of cases of MGNREGA workers who reported being paid Rs 130 to Rs 150 per day. In some cases, there were discrepancies in the personal details recorded on the workers’ job cards. Almost all were Dalits, belonging mainly to the Ramdasia, Valmiki, Majhabi and Majhabi Sikh scheduled castes, and a large number of those facing this form of wage theft were women.

“Favouritism by the sarpanch is very common in most parts of the state,” said agricultural economist Gian Singh, a retired professor of the department of economics at Punjabi University in Patiala, about MGNREGA workers’ complaints. There were also delays in payment, he told Article 14. “Also, they don’t get employment under the scheme for 100 days,” he said. “It is always less.”

By the end of August 2021, the average number of days of employment provided per rural household in Punjab was 20.90. Only five states had a lower average than Punjab, which provided an average of 39.52 days of work per household in 2020-21; 31.23 days in 2019-20 and 30.30 days in 2018-19, according to a February 2022 report by the Parliamentary standing committee on rural development and panchayati raj.

Caste Discrimination In Key Anti-Poverty Programme

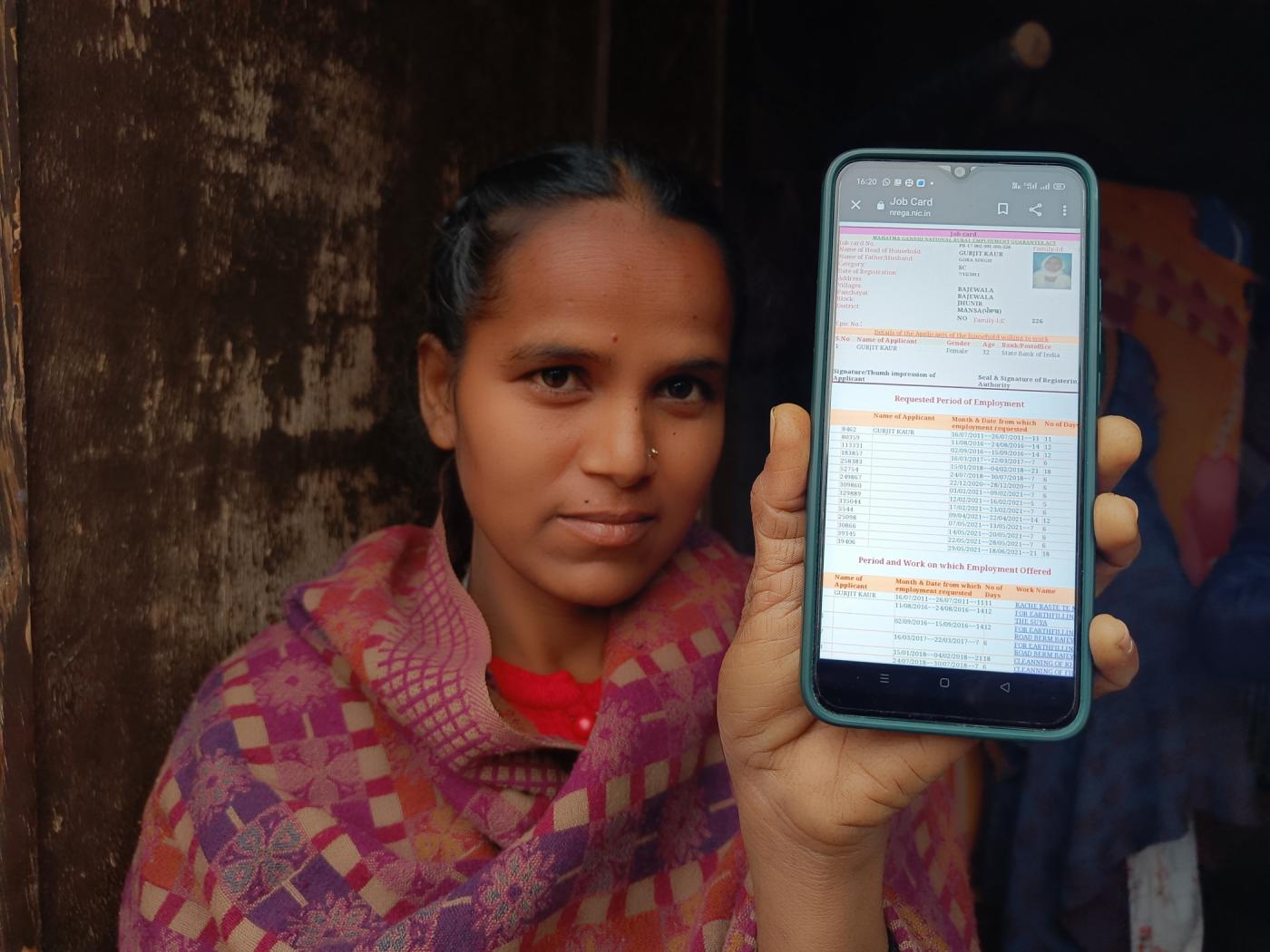

Gurjit’s job card, an essential document to seek work under the MGNREGA, bore somebody else’s photograph. She said she did not know who the other woman was. “Maybe she is someone getting the wages on my behalf,” she said. “It could happen.”

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/04-April/04-Mon/Gurjit%20Kaur%20.jpg]]

Rani Kaur of Mavi Sappan village in Patiala district recounted a similar struggle. Many others in the village had managed to build pucca homes, she said. “...ek sadda hi ghar nahi ban raha (Just ours is not getting done),” she said. According to Rani Kaur, the sarpanch got work done on the houses of people he favoured.

The 38-year-old Rani Kaur is physically challenged, as is her husband. The duo applied for a MGNREGA job card at least three times, but without success.

“I have polio and my husband has only one hand after an accident many years ago,” she said.

Rani, a Dalit, said her caste was the reason for the sarpanch not helping her build a house through a government subsidy or procure a job card. “He helps the upper caste and all his other friends and relatives.”

The village elite did not want Rani and others of her community to live near them, she said. “Their drain outlets come towards our kutcha houses.”

Krishna Singh, 50, the undefeated sarpanch of Mavi Sappan for 20 years, denied the charges. Speaking to Article 14, he said, “If I don't work for the people of other castes, then how have I been winning for the past four terms?”

Whether for housing or to procure work under MGNREGA, he claimed he has always assisted villagers across sections. Every scheduled caste family in the village has a job card, he said. “I don't have to pay from my pocket…It is a government scheme,” he said. “I never influence any government official.”

Patiala district collector Sandeep Hans said villagers facing any discrimination on account of caste or being underpaid under MGNREGA should submit a written complaint to him. “If the sarpanch doesn't listen to them, they must approach the panchayat officer or additional deputy commissioner - development.”

Promising strict action against any sarpanch found to be engaged in such discrimination, he said he would ensure that those left out of schemes such as the subsidies for home-building are covered.

Gagandeep, who goes by only her first name, president of the Dalit Dastan Virodhi Andolan and a Jalandhar-based lawyer, said caste discrimination against Dalits is still rampant in all three regions of Punjab, Malwa being the worst affected. “In our state, nobody wants to give agricultural or other labour work to lower castes,” she said. “So they rely on either collecting cattle dung for landowners or NREGA work.” Under the latter scheme, however, there are persistent challenges of delayed payments and low payments, she said.

Scheduled castes account for 31.94% of the population in Punjab. More than two-thirds of persondays of work generated under MGNREGA in 2021-22 (67% as of 25 March) were for SC workers.

According to the 2011 Census, of Punjab’s 12,168 inhabited villages, as many as 2,800 (23.01%) have scheduled castes, accounting for 50% or more of the population. According to the state government’s 2021-22 sub-plan for scheduled castes, a special budgetary outlay of Rs 10 crore was made for the overall development of these villages.

The reality, however, was that caste was a barrier to find work. Dalits often do not get work as agricultural labourers also, Gurjit Kaur said. Their choices were to take the MGNREGA work at whatever pay was determined, or clearing cow dung on landowners' properties.

“I even leave the children alone to go and work,” she said. “I must get my due wages.”

Sandeep Singh, 23, a resident of Mavi Sappan village in Patiala district, said well-off people in his village had job-cards though they never went to work sites. “The lower castes, who are landless, do not get the benefit they actually need.”

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/04-April/04-Mon/Sandeep%20speaks%20about%20her%20village.jpg]]

‘How Much Is Rs 132 Worth These Days?’

Rampal Singh, another resident of Patiala, said most workers he knew got work for 70 to 80 days during the year, but payments were made as per the wishes of his village’s sarpanch.

“I get Rs 132 as daily wage under NREGA,” said Rupa Kaur, a resident of Bathio village in Patiala. “Utne me kya honda aaj kal? (How much is that worth these days?)”

She said she managed to get work under MGNREGA for only six weeks through 2021-22. She did not get paid anywhere close to the state’s pay of Rs 269 per day even once.

According to Gian Singh’s book Socio-Economic Conditions and Political Participation of Rural Woman Labourers in Punjab, as much as 99.51%, or almost all, women agricultural labourers in Punjab belonged to the scheduled castes or other backward classes. The SCs alone accounted for 92.43% of women labourers.

Most are also uneducated, with Gian Singh’s book pegging 67.35% of women agricultural labourers in Punjab to be illiterate. This meant that Punjab’s women workers under MGNREGA were ill-equipped to demand their rightful wage or minimum guaranteed days of work as promised by the law.

Veerpal Kaur, about 50 years old and a villager in Mansa district, said she was paid Rs 100 per day on the few occasions when she got work under MGNREGA. “It is very difficult to get our names in the list of workers at first,” she told Article14.

“Once you speak against the sarpanch or even question him, you would never get your name in the MGNREGA list,” she said.

Others who worked with her received better wages—Rs 1,000 for seven days’ work, still just half the fixed rate fixed for Punjab. “They say I am old and so I would get only this much,” she said.

Veerpal never went to school, and Gurjit dropped out after class four.

Social activist Nikhil Dey, a founder-member of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), said the problem of low wages is common in many states. “In Rajasthan, the minimum wage rate is Rs 250 a day, the minimum NREGA wage rate is Rs 221, and the average NREGA wage received is Rs 180,” he said. “So it is obvious that many would be getting around Rs 150 per day.”

Dey, whose Rajasthan-based MKSS played a pioneering role in getting the MGNREGA enacted, said Punjab has witnessed poor implementation of the MGNREGA. At the fixed wage of Rs 269, people should earn Rs 26,900 a year from the MGNREGA for 100 days of work, but this hasn’t happened, he said. The complicated relationship between workers and the sarpanch is also a common complaint he has heard. “… to resolve their issues related to casteism, under-payment and more, they would need to have a group,” he said. “Because it is a battle.”

Mohinder Pal, deputy commissioner of Mansa, said it was not possible that workers were receiving such low wages. “If at all this is happening, this is a big problem. I have never heard a complaint of MGNREGA workers getting such low amounts,” he said, promising to look into the matter.

Under section 7 (1) of the MGNREGA, if an applicant is not provided employment within 15 days, he or she is entitled to a daily unemployment allowance.

Punjab paid no unemployment allowance in 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20, 2020-21 or 2021-22 as of November 15, 2021, the Parliamentary standing committee’s report evaluating the implementation of MGNREGA found.

Ramchandra Momiyan, a member of the NREGA Workers Union in Samana, Patiala, said the sarpanch doesn’t give citizens work when they seek it. “Since we don’t get work, we ask for berozgari bhatta (unemployment allowance), but we don't get that either. Earlier we had this option of working at the zamindars, but now our work is done by machines.”

(Jigyasa Mishra is an independent journalist based in Uttar Pradesh. She reports from north India on caste, gender, public health and environment.)