Patna, Bihar: “With reports of corruption in government jobs, my mother and brothers are now asking me to come back after my final examinations,” said Nidhi Kumari, a 23-year-old Bihar Public Service Commission (BPSC) aspirant.

The final exam to select close to 2000 officials for coveted government jobs—in departments as diverse as police, prisons, excise, education and labour—is expected to be held in May or June 2025.

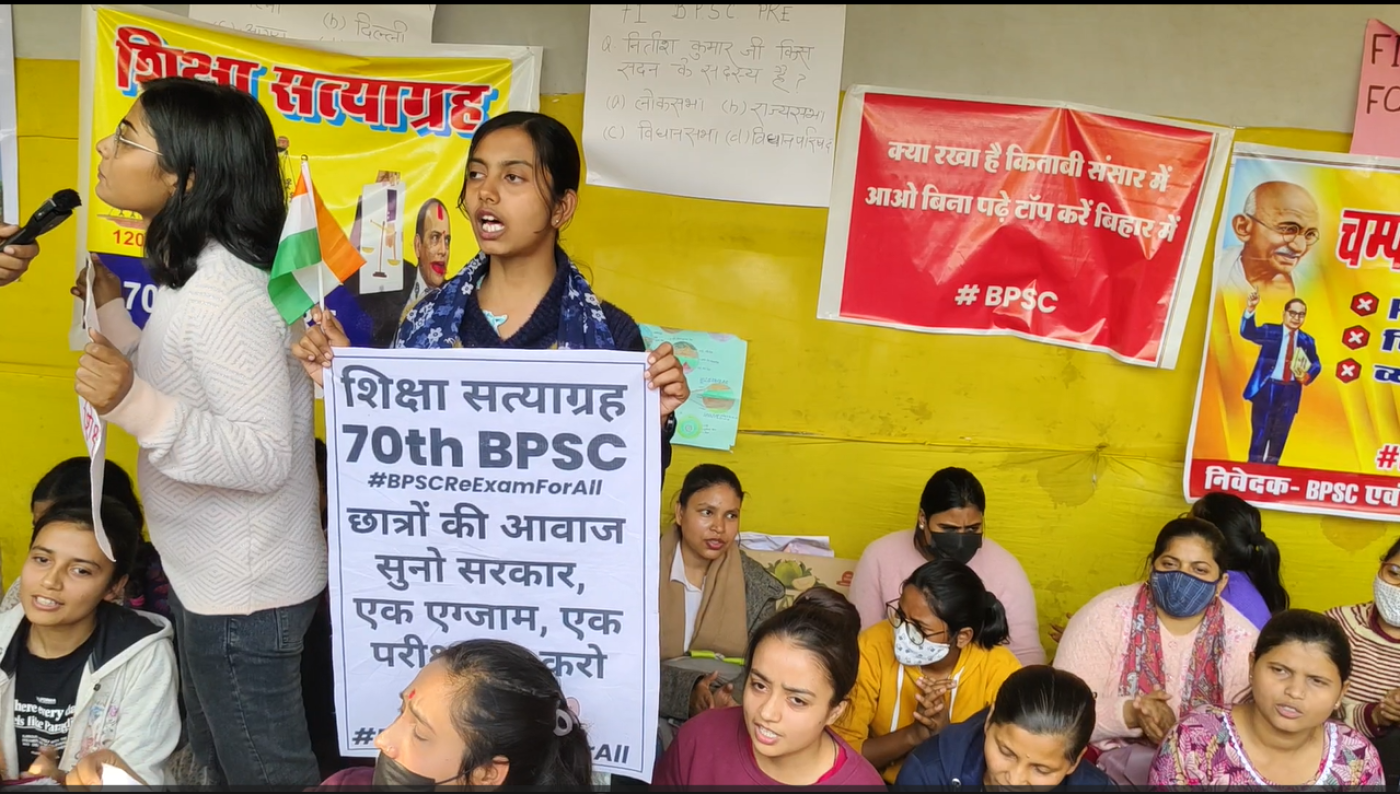

Nidhi Kumari participated in the December 2024 students’ protest in Patna, demanding a re-examination after accusations of irregularities, including delayed and missing questions papers, and a paper leak, in the preliminary phase of the 70th BPSC examinations on 13 December 2024.

During the BPSC aspirants’ agitation, many students alleged that 92 papers were missing in the combined competitive (prelims) exam at the Bapu Pariksha Parisar, India’s largest examination centre, in Patna, with over 8,000 aspirants.

Some students did not get the question paper, while many alleged that they got it half an hour after the exam officially began. There were allegations that the question paper was similar to test papers issued by coaching institutes.

A final-year master’s student of geography at Patna University, Nidhi Kumari is one of the many women in Bihar who aspire to get a government job to attain financial independence. For these women, government jobs are a path to stability and autonomy in a state marred by poverty and unemployment.

Stable employment outside the government is scarce in Bihar, indicators of which are India’s lowest labour-force participation and worker-population ratios, according to the latest available government data.

Opportunities for women are still fewer. For instance, 20.3% of women are part of the state’s workforce, compared with 31.7% nationally and 48.1% of men in Bihar, according to the latest periodic labour force survey reports issued by the union ministry of statistics.

The Tenuous Aspirations Of Women

Corruption in exams has become a formidable barrier for young women aspiring to secure stable employment, forcing many to abandon their aspirations and prompting families to withdraw support to daughters.

Nidhi Kumari previously took the examination for a government teacher’s job in March 2024—which also saw allegations of paper leaks—but was unable to pass it.

Bihar Police arrested 285 people in connection with the suspected paper leak.

Nidhi Kumari, who has a sister and two brothers, moved to Patna from Mokama, 90 km east of the state capital, to stay in a hostel and pursue her studies.

After her father died of a heart attack in 2024, Nidhi Kumari’s family’s economic conditions deteriorated. She said that her family still sent her money—from family savings—to pay her rent and other expenditures as an investment into her future government job.

But with the constant reports of fraudulent methods of selection procedures, she said, her family is now forcing her to come back and get married.

“My father has recently passed away,” she said. “Since I am the oldest child, my family has been pressuring me for marriage.”

‘Corruption From Top To Bottom’

Bihar, ruled by the Janata Dal (United) and various allies since October 2005, is one of India’s poorest states according to the United Nations Development Programme’s multidimensional poverty index of 2023

The state has long struggled with systemic corruption.

The 2019 India Corruption Survey, conducted by LocalCircles—a social media platform for communities and governance—and Transparency International India, a non-governmental organisation, found that 75% of the respondents from Bihar reported having to pay bribes.

According to 2022 data—the latest available—from the National Crime Records Bureau, 108 corruption cases were reported in Bihar, making it the state with the 12th-highest number of cases.

In January 2025, former deputy chief minister of Bihar and Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Tejashwi Yadav said, “Crime and corruption are two engines of the double-engine government in Bihar.” He was referring to Prime Minister Narenda Modi’s euphemism for having the same party governing state and Centre.

In November 2021, Yadav said, “There's corruption from top to bottom. Bihar stands first in unemployment, the education system has been completely destroyed, and health infrastructure in the state is in shambles."

The recent allegations of paper leaks and irregularities in the BPSC examinations have further exacerbated the crisis, leaving women aspirants in a state of despair.

“We study to change our lives and contribute to society,” said Nikki Kumari, a 33-year-old hoping to get a government job through the BPSC examinations. “But how can we hope for a better future when the system is stacked against us?”

Kalpana Kumari, a 23-year-old BPSC aspirant from Darbhanga district in Bihar, moved to Patna two years ago to prepare for her examinations.

Kalpana Kumari said that she tutors children to earn pocket money, but the reports of corruption in government exams have lowered her morale.

"Qualifying for a government job will give me space to breathe,” she said.

A Failing System

Sandhya Kumari, a BPSC aspirant in her late twenties, got pregnant soon after marriage—her husband is a railway technician—but suffered a miscarriage. She restarted her journey to prepare for the examination in early 2023.

Sandhya Kumari said finding a government job was her dream. She passed the preliminary BPSC examination in 2024 but failed to qualify in the mains.

Sandhya Kumari is from Mohiya village of Kaimur district in Bihar but moved to a hostel in Patna, over 100 km from her hometown, to prepare for the examinations.

Sandhya Kumari said her husband initially supported her financially while she prepared for the examinations, but now he and her family want her to return home to try again for a baby.

“While now I wanted to try after qualifying for the examinations, the constant pressure from the family and reports of corruption in the selection procedure has left me with less hope of qualifying,” said Sandhya Kumari. “Now, I don’t want to resist the demands of my family and may leave my preparation midway to stay with my husband and restart my marital life.”

A Recurring Pattern of Examination Corruption

Ramanshu Mishra, a tutor for BPSC examinations in Patna said, “Whenever lucrative positions like sub-divisional Magistrate (SDM) and deputy superintendent of police (DSP) are up for grabs, cases of paper leaks and backdoor appointments surge.”

In December 2024, the BPSC exam was held for 2,031 positions, including 200 SDMs, 136 DSPs, and other gazetted officers.

Many students went on hunger strike in Patna, demanding a re-examination.

The BPSC announced it would conduct a re-examination, on 4 January 2025, of the test held at the Bapu Pariksha centre alone—one of the 912 centres—due to a “disruption”, according to BPSC chairperson Parmar Ravi Manubhai, leading to dissatisfaction among aspirants.

Vice-president of Janata Dal (United), Prashant Kishore, and members of other opposition parties also joined the protest at Patna's Gandhi Maidan.

A first information report was filed against Kishore, party president Manoj Bharti and others for "organising a gathering of students" in defiance of a “warning that any demonstration there would be considered unauthorised”, according to district magistrate Chandrashekar Singh.

Rajesh Ranjan alias Pappu Yadav, a member of Parliament from Purnea, Bihar, and his supporters were booked for blocking railway operations to express solidarity with the agitating BPSC candidates.

Corruption in the examination procedure of government exams in Bihar is not new. Similar allegations of corruption were made in 2022 during the 67th BPSC examination.

These allegations are not limited to the BPSC examination.

There were reports (here and here) of question paper leaks in the 2017 Bihar staff selection commission examinations.

In 2022, there were reports of paper leaks at the combined graduate-level examination conducted by the staff selection commission.

Even the state government teachers recruitment exams, conducted in 2024 for 120,000 posts, saw similar accusations of corruption and paper leaks.

Why Govt Jobs Matter

“People find government jobs lucrative as it is a permanent job,” said Pushpendra Kumar Singh, a former professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and chairperson of the Centre for Development Practice and Research, Patna. “As there are fewer government jobs and more people want it, the hype around the government sector is more,” said Singh.

“Thus, many people are willing to pay an exorbitant amount to get the job, resulting in corruption in the selection procedure,” said Singh.

Bihar has one of the highest unemployment rates in India, with unemployment in the 15-29 age group at 13.9%, according to the 2024-25 budget presented by Bihar’s finance minister, Samrat Chaudhary.

This is higher than the national unemployment rate of 10%.

Most development in Bihar is centred around the state capital, Patna, and cities, such as Rohtas, Muzzafarpur, Begusarai, Munger and Bhagalpur, while the rest of the state has fewer jobs.

Many positions in government departments, such as health, education, IT, and accounts, have been outsourced to private organisations that hire employees on contract. For example, from 2006 onwards, around 4,500 IT jobs were outsourced to Beltron, a consulting firm.

After the outcry over the leak of the question paper of the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (undergraduate)—the nationwide examination for admission to undergraduate medical programs—the Bihar government passed the Bihar Public Examinations (Prevention of Unfair Means) Act (2024) in July 2024 to curb exam paper leaks.

However, exam malpractice has continued regardless of the stringent punishment—a three to five-year prison term and a fine of up to Rs 10 lakh—outlined in the Act for those found guilty of malpractice in government examinations.

The Act also punishes agencies conducting tests, with fines of Rs 1 crore and bans them for up to four years.

Disproportionate Impact On Women

According to the 2011 census, Bihar’s literacy rate was 61.80%, almost 12% lower than the national average of 74.04%.

There was a stark gender disparity in literacy, with male literacy at 70% in 2011, and female literacy at 53%.

These rates were even lower in rural Bihar, where the female literacy rate was 29.6% in 2011, compared to 57.1% for males.

The National Health and Family Survey-5, 2019-21, the latest available data, showed a slight improvement in the female literacy rate: 55% compared to 76.4% in men aged between 15 and 49.

While the government and civil society groups attribute the low literacy rate to various factors, such as poverty and child marriage, Sandeep Saurabh, a Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation member of legislative assembly representing Bihar’s Paliganj constituency in the Patna district, told Article 14 poor job prospects were a major reason.

He said students often migrated for employment or depended on government jobs due to limited opportunities.

"With the constant reports of corruption in examinations...people from marginalised communities refrain from spending on the education of their children,” said Saurabh. He added that women were the most vulnerable as parents prefer getting them married rather than paying for their education.

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey, the female labour force participation rate in Bihar in 2023-24 was 20.3%, while for males it was 48.1%. This makes women economically dependent on male family members.

In 2016, Bihar reserved 35% of government jobs for women, which encouraged many to sit government selection examinations and increased women’s participation in the workforce.

“But, in many cases, people pay bribes to get the jobs,” said D M Diwakar, former director and professor of economics at the A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna. “Under such circumstances, the chances of women paying bribes to get the job are low, limiting their chances in corrupt recruitment systems.”

“If the corruption is high in the selection procedure, it majorly affects the people from the marginalised community who dream of getting a government job to transcend their caste and class barrier,” said Singh.

Disagreeing with the argument that women's literacy could decrease as a result of corruption charges in the selection procedure, Diwakar said, “However, with constant reports of corruption in the selection procedure of the government examinations and low job prospects, parents get discouraged from educating their children.”

‘They Will Prefer Paying My Dowry’

“I had qualified for the BPSC mains earlier and had also taken the exam for the Combined Defence Services,” said Chanda Kumari, a government job aspirant, who had failed to qualify for the final interview stage in the previous exam, held in 2024. “All I aspire to is to get into a government job to contribute to the welfare of the society.”

The 23-year-old said her parents would rather see her married than continue preparing for exams, partly due to the costs of competitive exam coaching.

“They will prefer paying for my dowry than paying for my coaching,” said Chanda Kumari.

(Yusha Rahman is a Bihar-based fact-checker and freelance journalist.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.