Delhi: In the 58-year history of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, public and parliamentary opposition to it has underlined the potential for its use against political opposition, the indiscriminate use of it against minority communities, definitional vagueness, and the power to detain, arrest, torture and prolong trials for years.

“It is a case of a Government that is greedy for power, wants more power and does not know how to use the powers that it has already got,” said Dahyabhai V Patel, the son of Sardar Vallabhai Patel, representing the Swatantra Party when the UAPA was being debated in 1967.

“Why do they want such powers again and again?” he asked.

The UAPA was originally enacted to criminalise “unlawful activities,” defined as any action taken by an individual or association that supports any claim to bring about the secession of any part of the territory of India from the union, disrupting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of India, or causing disaffection against India.

In 2004, the UAPA was amended to include provisions that punished acts of terror in addition to criminalising unlawful activities, following global trends to combat international terrorism.

The UAPA is a law that functions as a stand-in for arresting, detaining, and imprisoning anyone. Vague definitions in its language on what constitutes a terrorist act or unlawful activity create an ambiguous cloud of criminality over any person.

Section 43D(5) was introduced in 2008 following the terrorist attacks in Mumbai, setting a very high bar for bail, making it virtually impossible despite recent Supreme Court judgments interpreting this restrictive provision through the prism of the fundamental rights of life and liberty and the right to a speedy trial.

Further, in 2019, under the home minister Amit Shah, sections 35 and 36 of the UAPA were amended to allow the central government of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to designate individuals, and not just organisations, as terrorists.

This amendment is more dangerous given the additional solicitor general SV Raju’s recent arguments before the Supreme Court in a Delhi riots case against Muslim students and activists that “intellectual terrorists are more dangerous than those working on the ground”.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), between 2014 and 2023, a total of 17,723 people were arrested across India under the UAPA, in 9,469 cases, of whom 12,083 were chargesheeted. 474 (2.6%) were convicted. For the same period, 981 persons were acquitted or discharged.

Weaponised Against Muslims

Our data on the use of UAPA from January 2005 to February 2025 in Karnataka, researched and produced at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, over three years, show the extent to which the UAPA has disproportionately targeted Muslims.

The analysis of this data is centred on “incident” rather than “FIR” and on the individuals implicated.

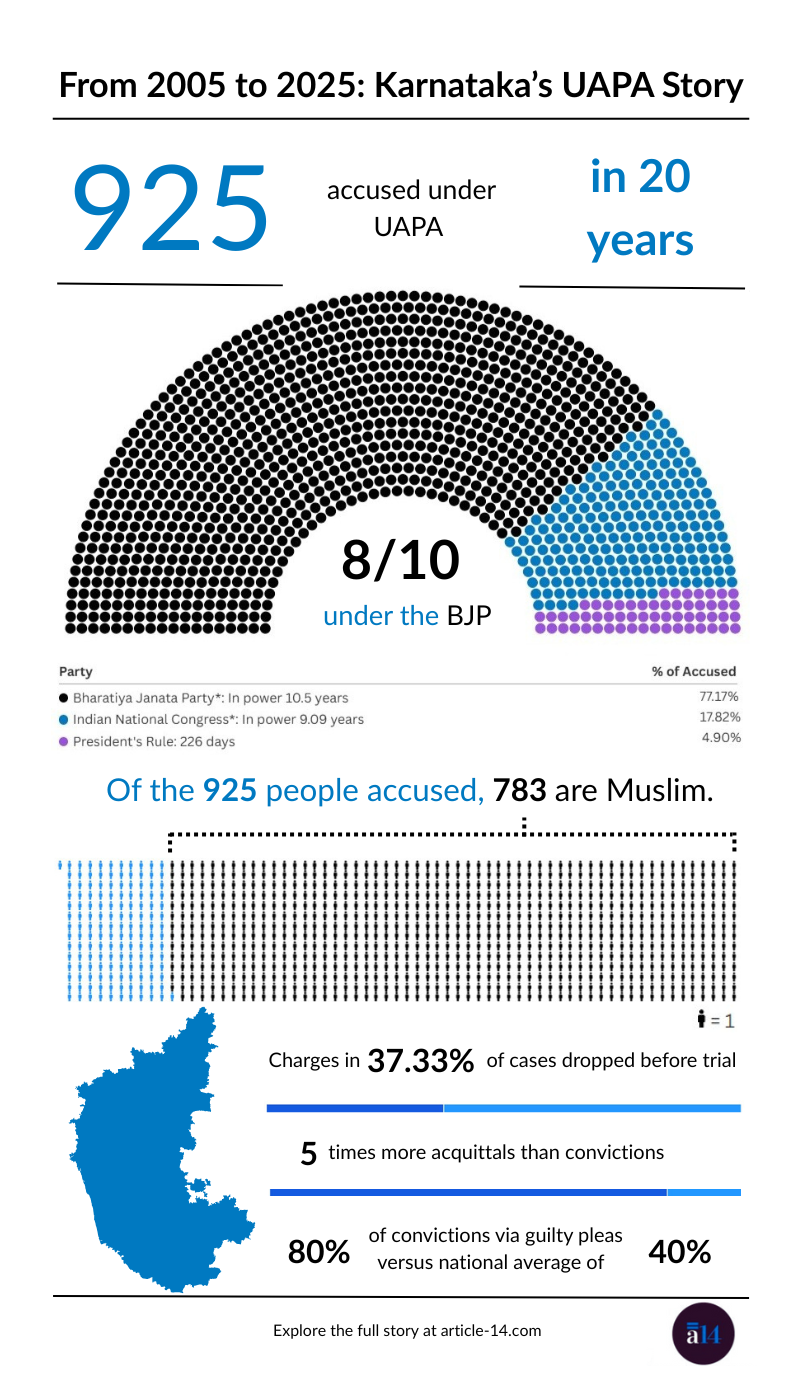

We analysed 95 incidents involving 925 persons and 1,125 cases from these incidents.

Many persons have multiple FIRs (First Information Reports) against them, each of which can result in multiple cases before courts. Therefore, the total number of cases (namely, acquittals, convictions, ongoing cases, charges dropped/withdrawn, discharges by courts) is more than the total number of persons accused under this law.

Using the term "incident" also enabled deeper analysis of the backstory of an “incident” being converted into an FIR and of how incidents are interlinked to create conspiracies and cases.

Karnataka has seen nearly equal periods of rule by the Indian National Congress (9.09 years) and the BJP (10.5 years), and President’s Rule for 226 days. The Janata Dal (Secular) was in coalition with both parties intermittently over the past 20 years.

Nearly 8 in 10 persons accused under the UAPA in Karnataka were during the 10.5 years the BJP was in office. In other words, the BJP invoked the law 5.2 times more than the Congress Party in Karnataka over the past twenty years.

Of the 925 persons, 783 (84.6%) were Muslim.

Of the 925 persons, 20.16% were accused under Section 18 for conspiring to commit a terrorist act, 16.4% under Section 16 for punishment for terrorist acts, 15% under Section 20 for being a member of a terrorist group or organisation, and 13.4% for unlawful activities, and 6.33% for being a member of unlawful associations.

As our data show, despite charges of conspiracy often being made on thin to no evidence, even when fabricated, it remains the section most commonly invoked by investigating agencies.

The penalties for unlawful activities and membership in unlawful associations are punishable with five to seven years in prison, while terrorism-related activities are punishable with at least five years and carry maximum punishments of life imprisonment and the death penalty.

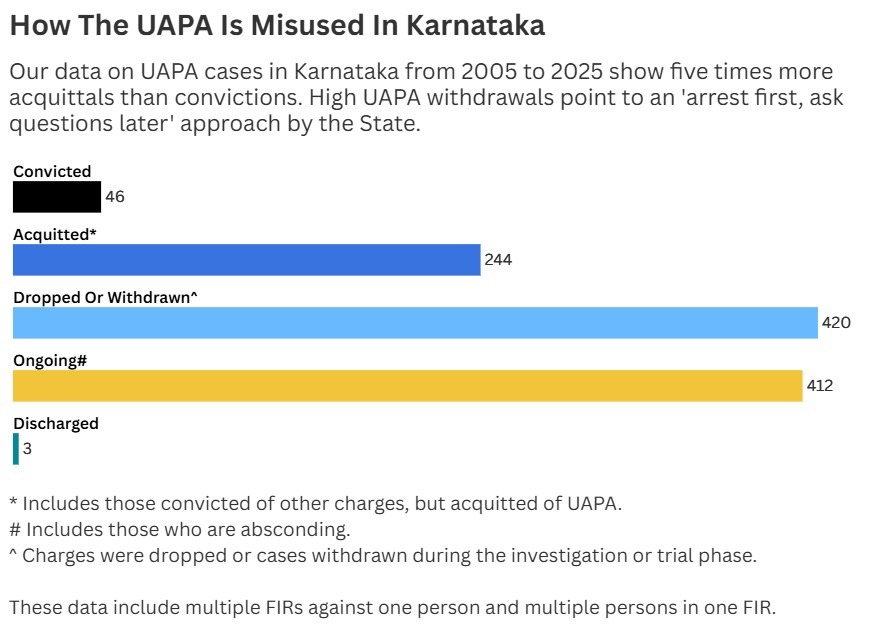

Charges were dropped in 37.33% of the 1125 cases before trial, and among those that proceeded, acquittals outnumbered convictions by a 5-to-1 margin.

Notably, four out of five convictions resulted from guilty pleas rather than contested trials, raising questions about the strength of evidence and the pressures shaping case outcomes. (A recent report, The Forced Guilt Project, matches this finding about the National Investigation Agency (NIA) forcing guilty pleas to secure convictions.)

The main findings of the research show that:

- Nearly 8 in 10 of the persons accused under the UAPA in Karnataka were booked during the 10.5 years the BJP was in office.

- Of the 925 individuals accused under this law in this period, 783 (84.6%) are Muslims

- Charges in 37.33% cases were dropped before reaching trial

- 5 times higher number of acquittals than convictions (244 persons acquitted versus 46 convicted)

- 80% of convictions in Karnataka were secured through guilty pleas

- The national average of accused pleading guilty is 40%, as our data from all cases investigated by NIA reveal.

These patterns will be explored in Parts 2, 3, and 4 of this series.

Why A State Study

This research began in 2022, shortly after the release of Article 14’s “A Decade of Darkness”, which examined the use of the sedition law over 10 years.

Article 14 extensively mined data from public, open-access, court, police, and media websites and combined it with investigative reportage.

Using similar methodology for sourcing and analysing data, and bringing together an interdisciplinary team of lawyers and journalists, this database began as an all-India endeavour.

The all-India approach to mining data from open-source and government websites for UAPA, however, quickly revealed operational challenges.

The E Courts portal, a state-led, open-access, public repository of all trial court records, for instance, showed little to no case entries for states that should reflect hundreds of cases. For instance, a manual data scraping session for every district court in J&K showed that 16 out of 20 districts did not have UAPA listed as a law in the drop-down menu. This means it is difficult for an individual to view any records related to UAPA in these districts on a government website that is open to the public.

In our data-mining exercise, courts in 134 districts across India did not have UAPA listed in the drop-down menu. Data scraping technology, therefore, cannot address the difficulty of raw data being unavailable.

Bail orders, judgments, chargesheets and FIRs were not consistently uploaded, particularly for cases between 2000 and 2010 across India. Special NIA Courts in Patiala House and Lucknow, in particular, did not upload orders for all cases. This could also be attributed to the better digitisation of court records after 2010, under the E-Committee of the Supreme Court of India. Barring the names of the parties and the sections they were charged, there was often no other detail available to triangulate this data with media sources.

Efforts were redirected towards unearthing state-specific data on Karnataka covering 20 years.

Karnataka showed the most promise in terms of data availability on government websites. The increased availability of data in Karnataka from 2010 onwards can also be attributed to the phase-wise digitisation of court records.

Why Incident Rather Than FIR

The analysis “incident” rather than “FIR” is to consolidate the multiple FIRs and combined trials that occur in the aftermath of an incident. Further, investigating agencies often implicate the same person across multiple FIRs or multiple people in a single FIR.

For instance, after the 2008 serial bomb blasts in Bengaluru, the police filed nine FIRs. Each FIR listed between 100 and 200 persons. Courts subsequently combined trials for most of the accused.

Significant incidents around which this phenomenon was observed were the 2005 Indian Institute of Science Attack, 2008 Bengaluru Serial Bomb Blasts, 2010 M. Chinnaswamy Stadium Bombing, 2020 Bengaluru riots and 2022 Hubbali riots.

Further, for incidents involving left-wing activities, the challenge was that many of the accused remained at large for years. This means many cases were never committed for trial, making them difficult to find for the database.

Over the years, as many accused surrendered or were found, the trials of these cases—even if the incident was a decade old— resumed. This also meant that, in our analysis of outcomes, these individuals were not unique, as multiple cases were filed against a single person. (The highest was at least 34 FIRs filed against one person in left-wing related activities).

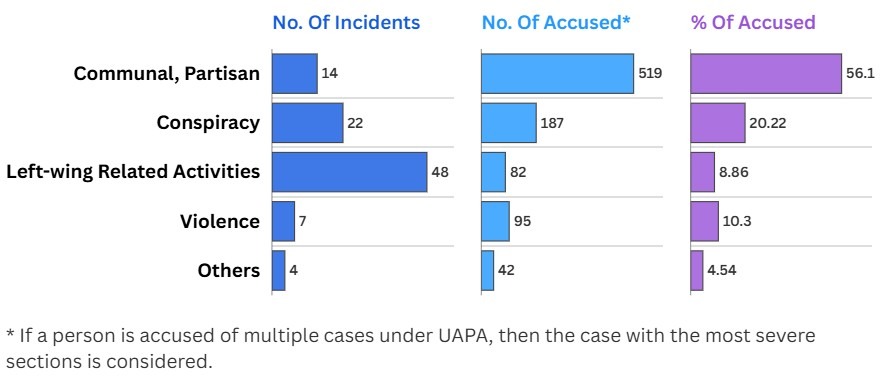

The data was further categorised based on the nature of the incident:

- Violence, such as bomb blasts or mass shootings. There have been seven such incidents, which have cumulatively claimed three lives.

- Conspiracy by association is an incident in which persons are alleged to be associated with proscribed organisations, to have conspired to plan an attack, or to have supported or recruited for these organisations.

- Communal/Partisan incidents are those filed against persons accused of spreading hatred among communities. This includes participating in protests, making hateful speeches, or arrests made after assaults or murders of RSS/BJP activists.

- Left-wing related activities, where persons were accused mainly of furthering the Maoist ideology.

- Others include charges of possession of counterfeit currency and human trafficking.

Many of those who were accused, were out on bail, were acquitted, or were released after serving their sentences, did not want to speak to us. Many had also moved from their original homes. We interviewed 11 accused and six lawyers who have handled several UAPA cases in Karnataka. Those who were accused and agreed to be interviewed spoke on condition of anonymity.

Making A First Information Report

Research has extensively documented how a case under the UAPA is made. These ‘conspiracies’ rely on thin to no evidence, starting with profiling, surveilling, and ultimately implicating those belonging to minority communities, obtained under custodial torture, and fabricated evidence.

As a doctor who was accused under the UAPA told us, “During Ganesh Chaturthi, when I know the processions may lead to some unrest and violence, I close my clinic and sit at home. If there is some violence, I know the police will round up Muslim men, and I don’t want to be at my clinic at the time.”

Office-bearers of Popular Front of India (PFI), an Islamic right-wing organisation that was banned under UAPA in 2022, are accused in multiple cases of terror conspiracy and the murder of members from right-wing Hindu organisations.

The interconnected web of UAPA cases ensures longer prison terms, as an accused in one case can be booked for similar conspiratorial cases in other places. These interlinkages are obtained through “voluntary confessions” by the arrested, call records, or even having met each other once, being present at the same event, or being in the same house.

One example is in the 2022 murder of a BJP worker, Prashant Nettaru, where those accused were allegedly part of the Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI), a political party linked to the banned PFI.

One of the accused in this case, eventually charged under the terrorism provisions in the UAPA, held a meeting at his house, with his brother present. His brother, as he told us, had a habit of doodling. At the meeting, he doodled some roads, a house and other objects. The NIA subsequently accused him of drawing a master plan and had forensic experts tally the doodle to his brother’s handwriting to prove that they had conspired to kill Nettaru.

In another terrorism case registered in 2008, members of a football team, all Muslim, in Belagavi, Karnataka, were arrested. The arrest began with one team member who was curious about the war in Afghanistan and was watching videos about it. The police claimed that all members of the team were therefore involved in some form of conspiracy.

In yet another case in 2008, a Muslim man was charged under the UAPA for pasting pamphlets protesting the 1991 Babri Masjid demolition as part of his alleged involvement with the Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI). These sections punish both unlawful activities and terrorism. In an interview with us, he asked, “How many cases can they file for a 6*8 inch pamphlet? They filed 6 cases.” He was acquitted in 4 out of 6 cases; two are still pending.

Four common suspects link a terror case involving LeT and Taliban slogans in Mangaluru in November 2020; the stabbing of a shopkeeper after communal riots in Shivamogga in August 2022; and a “cooker-bomb” blast at a cafe in Bengaluru in March 2024. Of the four, two suspects were further linked to the murder of a police sub-inspector in Tamil Nadu in 2020. The NIA is investigating all these cases.

The NIA—whose case list is riddled with inter-connected conspiracy cases—attributes this to an ISIS network being guided by an anonymous digital handler.

High Acquittals Expose UAPA’s Overuse

Our data on Karnataka show a substantial gap between the number of people accused under the UAPA and those who are ultimately convicted, acquitted, or discharged by courts.

In addition to 21.7% of cases resulting in acquittals, the data show a high withdrawal rate of 37.33%, indicating serious overreach by the government in invoking such grave charges in the first place.

Left-wing-related incidents resulted in the highest number of acquittals over 20 years.

As one lawyer who represents those accused in these incidents said, “the police find tents and food in the forest and stitch a charge of disruptive activities intended to bring down the government. Most cases involve finding pamphlets, writings, tents, and food. They don’t hold up in court.”

Part 4 of this series will reveal how weak evidence, shoddy investigations, and absent or hostile witnesses lead to acquittals.

As our research shows, even a conviction is tainted.

In some cases, investigating agencies encouraged accused persons to plead guilty under section 229 of the Criminal Procedure Code, using the length and uncertainty of the trial process as a tactic to allow them to leave prison with time served as an undertrial.

As one anonymous person who pleaded guilty in a case of an interconnected ISIS module told us, “If I pleaded guilty, I would be out in a year and be with my family. If I didn’t, I’d wait years in the hope of being acquitted. By then, does it really matter? What kind of employment am I going to get, whether I’m guilty of a terror case or I’ve been acquitted of it?”

Evidence-Free Narratives

In 1967, Dahyabhai Patel, when opposing this law, said, “When it suits them (the government), they say that the situation is getting out of hand and they want emergency powers.”

Patel was right that the UAPA is not designed to uphold notions of guilt or innocence through acquittals and convictions, but is instead adapted by all governments in power to create what Indian Army chief General Upendra Dwivedi called the “narrative management system”.

In 1967, it was the Congress Party, insecure about its own future in Indian politics, that passed this law amid talk of secession in Tamil Nadu, Assam, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Jammu and Kashmir.

By 2025, the BJP has inherited these insecurities and built on this legacy through its use of the UAPA.

A particularly chilling legacy under this law is the one Iqbal Jakati, a 53-year-old father of three, recounted to us.

He was acquitted under UAPA in 2011, having spent three years in prison. But a case was filed against him after his release, under Section 153-A of the Indian Penal Code, which punishes promoting enmity between different groups on account of religion, caste, language, etc., after riots broke out following an Eid procession.

He said he wasn’t even there. The case was ultimately dismissed before the trial.

He said, “My wife asked me whether this was the legacy I would leave for my children, chargesheets and FIRs.”

First of a four-part series. Read Part II here, Part III here and Part IV here.

Names of those interviewed have been withheld on request.

Investigative reportage, data mining, research & analysis for Karnataka, Mohit Rao; All India data mining and analysis, Sakshi R., Nikita B; Research on acquittals in UAPA in Karnataka, Zeba Sikora; Background research, Vibha S.; Research Direction, Lubhyathi Rangarajan; Principal Investigator, UAPA Data Series, Mayur Suresh; Edited by, Betwa Sharma.

This data is produced by a research project at SOAS, University of London, funded by the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.