Mumbai: One evening in October 2020, Varanasi resident Kausar, 26, returned from an exam to find a small crowd gathered at her home in Lallapura, the bunkar mohalla or weavers’ colony in the heart of the city. Her brother Neyaz, younger by a couple of years, had taken his life.

“It was my mother who found him hanging,” said Kausar, who uses only a first name.

A former handloom operator, Neyaz had run the family’s finances since their father, a former handloom operator, died in 2012. He earned Rs 8,000-Rs 9,000 a month buying sarees from Surat for stone-embossing and other embellishments in Lallapura, where almost every family depended on the artisanal textile industry for their livelihood, operating or working on handlooms or powerlooms, or doing embroidery, zardozi or ancillary trades such as loom repairs.

“Work had stopped completely due to Corona,” Kausar told Article 14. “He had no work, kuch bhi nahin (nothing at all), for months at a stretch.” As the family struggled to find food—they were four sisters, three brothers and their mother—and Kausar and a younger brother began to look for work, Neyaz brooded for days.

He had bought Kausar books to prepare for UPSC exams, paid her fees to complete her MA in political science from Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith.

Kausar worked at a cable-TV operator’s office for about a year after her brother’s death, earning Rs 4,500 a month handling set-top box recharges. She lost that job in April 2022—her employer could no longer pay her salary. “I am jobless again,” she told Article 14. In the evenings, she sat with her mother and sisters making jhaalars (the decorative end) on sarees. It took six to seven hours to complete one saree, for which her mother would earn Rs 120. There was not enough demand to work on more than one saree at a time.

“Neyaz took that step because there was no work to be found,” Kausar said. “And now there are still no good jobs, neither in the textile sector nor outside.”

A tense hush has fallen over scores of weavers’ colonies in the state, said Muniza Khan, PhD, the field coordinator for a detailed report on the impact of Covid-19 on eastern Uttar Pradesh or Purvanchal’s traditional textile industry, published by nonprofit Citizens For Justice And Peace (CJP).

The wrecking of employment in the Purvanchal loom industry represented similar bloodbaths in micro, small and medium enterprises everywhere. “For every registered weaver, there were 12 to 15 dependent livelihoods—men who maintain looms, designers, washers, yarn spinners, dyeing workers, dye sellers,” said Khan. “And every one of them is still to recover from the devastation caused by the pandemic.”

The lockdowns, the casual nature of most work available post-lockdown and absence of quality jobs sharpened employment-related distress. Suicides on account of unemployment rose, said minister of state for home Nityanand Rai in Parliament, quoting National Crime Records Bureau data to say there was a 24% jump in the number of unemployment-related suicides in India in 2020 compared to the previous year.

According to data tracked by private business information and analytics firm Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the rate of unemployment in India in April 2022 was 7.83%, up from March (7.57%), appearing set to climb back to February levels (8.11%). The unemployment rate is the percentage of job-seekers without work.

“India’s biggest sign of economic distress”, according to a CMIE report, came in March 2022 when the count of the employed and the unemployed both fell.

The labour force (people working or actively looking for a job) shrank to its lowest in eight months, while the number of those employed shrank to the lowest level since June 2021. The count of the unemployed fell too—for millions were no longer looking for work as India’s labour force participation rate fell to 39.5% in March 2022, lower than during the second wave of Covid-19 in April-June 2021.

The government of India said the CMIE’s inference was factually incorrect because large numbers were employed in unpaid work or were pursuing education. In addition, the government said that the ministry of statistics and programme implementation’s Periodic Labour Force Survey showed an increase in the labour force participation rate between 2017-2018 (49.8%) and 2019-2020 (53.5%).

The employment situation in the country was already “dire” in 2017-18, said professor Ravi Srivastava, director at the Centre for Employment Studies, Institute for Human Development, Delhi. He said while there were discrepancies between the CMIE and PLFS datasets on account of varying methodologies and concepts, the PLFS reports themselves showed a significant deterioration in employment between 2011-12 and 2017-18.

The post-pandemic revival in some segments had seen some sectors facing labour shortages, mainly of skilled workers, “almost the upper-end of the informal economy”, but the distress in employment is “still very, very broad-based and that is reflected in the aggregate figures”, according to Srivastava.

These unemployment aggregate numbers are higher today than in 2017-18.

Indeed, India’s current unemployment crisis did not emerge overnight, nor even only on account of the pandemic—India’s labour force participation rate, down from 46% to 40% between 2017 and 2021, was already lower than many other Asian countries, for example. In 2020, workforce participation in Nepal stood at 77.3%, in Vietnam at 74.7%, in China at 68.2%, in Malaysia at 64.9% and in Bangladesh at 56.7%.

The pandemic-induced meltdown in India’s job market is only one part of India’s unemployment story, and consequently, attaining pre-pandemic levels of unemployment should not be policy-makers’ goal, warned economists and experts.

Disaggregating Data: Who Is Unemployed & Where

For the month of April, CMIE’s data pegs all-India unemployment at 7.83%, but eight states recorded double-digit unemployment levels—Haryana (34.5%), Rajasthan (28.8%), Bihar (21.1%), the union territory of Jammu & Kashmir (15.6%), Goa (15.5%), Tripura (14.6%), Jharkhand (14.2%) and Delhi (11.2%). Some showed wide variations in unemployment levels, but others including Bihar, Rajasthan and Jammu & Kashmir recorded job distress for several months in a row.

In Bihar as in Jammu & Kashmir, educated youth were among the worst hit.

Article 14 has reported that chemistry graduates and taxi drivers in Kashmir were working at construction sites, more than a million were not even looking for jobs. Unemployment among educated youth in Jammu & Kashmir was 46.3%, behind only Kerala where the number is 47%, according to thePeriodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for April-June 2021.

A quarter of young Indians in the 15-24 years age bracket could not find work, according to a modelled estimate for 2020 by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) that pegged youth unemployment in India at 24.9%. The corresponding number for Bangladesh was 14.8%, Indonesia 14.5%, Bhutan and Malaysia 14%, Vietnam 7.3% and Cambodia 0.8%.

According to a CMIE report for January-April 2022, the number of unemployed in the 20-24 yrs age bracket was estimated at 20,092,000, a 42% unemployment rate. Unemployment in the 25-29 age group was 6,008,000, a 12.72% unemployment rate. Together, the unemployed in the 20-29 years age group constituted nearly 80% of the 32,102,000 unemployed Indians above 15 years of age who were actively seeking work but in vain.

In 2018, as fertility rates declined, India embarked upon a key demographic transition as its working age population began to grow larger than the population of dependents aged below 14 years or above 65, achieving that vaunted ‘demographic dividend’ that countries such as Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and others utilised to pave the way to economic growth, with an increased focus on education, job-creation, skilling and health for young people.

India’s unemployment crisis unfolds during that window of opportunity to achieve quicker economic growth, but the demographic dividend has increasingly appeared to be a liability, on account of high unemployment among youth.

“Young and unemployed people are more and more desperate,” said students’ union leader Dilip Kumar of Bihar’s Rashtriya Chhatra Ekta Manch who led a series of Twitter hashtags in the weeks before the January 2022 violence involving railway job aspirants across Bihar. “There were lakhs of retweets to our tweets, and students got more and more agitated because the government and Railways seemed to not heed our social media struggle.”

Aspirants for government jobs in Bihar have formed tens of thousands of study groups in district and block towns and at the panchayat levels, to prepare together for the Railway Recruitment Board and other exams. Thousands of such students were on DIlip Kumar’s WhatsApp and Telegram groups, all restive after waiting in vain since 2019 for the recruitment process to begin for various categories of jobs in the Railways.

“There is no industry or other job avenue for them in Bihar,” he told Article 14. Jobs in the Indian Railways were traditionally the most sought after among educated Bihari youth, he said. “Graduates who don’t get those jobs remain unemployed for years.”

The 2017-18 PLFS compared unemployment rates across different educational levels as captured by the NSS 61st (2004-05), 66th (2009-10), 68th (2011-12) rounds and PLFS (2017-18) data. It showed that unemployment rose over time along with education levels, for example for rural females with a secondary education and above from 15.2% in 2004-05 to 17.3% in 2017-18; for urban males with a secondary education and above from 5.1% to 9.2%.

In Haryana, several dozen unemployed young men conducted a protest march in Rohtak city on 8 May to demand resumption of recruitment to the armed forces. Former chief minister Bhupinder Singh Hooda was quoted as saying the state’s youth were getting “caught in the grip of crime and drugs” on account of unemployment. He was speaking in the context of a young man’s death by suicide in Bhiwani district, apparently on account of unemployment and frustration at crossing the age limit for recruitment to the armed forces.

One of the biggest reasons for India’s low overall labour force participation rate is the abysmal level of women’s participation in the labour force, one of the lowest in the world. For the October-December 2021 period, according to the PLFS quarterly bulletin, female participation in the labour force (all ages) was 16%. Male participation was 57.6% and overall labour force participation rate was 37.2%.

Women struggled to return to the labour force post-pandemic, but pre-pandemic years’ data show that the downward trend had begun much earlier, going from 32% in 2005 to 21% in 2019, the lowest rate in South Asia.

The dominant narrative has been that women choose to stay home as household incomes grow, but studies have shown (here and here) that other factors impact women’s employment, including whether part-time, proximate and flexible employment suitable to their needs is available.

India’s ‘Rural-Led Recovery’ Is A Misnomer

Data from the website of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), India’s showcase workfare programme, showed a dip in households demanding work under the programme in April 2022 (23.2 million households) as compared to April 2021 (26.1 million households). Forced to return to native villages in droves by the lockdowns, a record number of workers had demanded work under MGNREGA in the summer of 2020 and 2021.

The significant dip (about 11%) in April 2022 suggested a reduced dependence on the rural jobs guarantee programme as migrant workers returned to cities. However, the demand remained higher than in the same month in pre-pandemic years—16.8 million households in April 2018; and 21 million households in April 2019.

In most labour market metrics, rural India has shown quicker improvements post-pandemic, prompting the government to suggest that India was witnessing a rural-led recovery, with the agriculture sector growing at nearly 3% per annum during the pandemic months.

“The task of raising rural employment levels in India is not something limited to moving to pre pandemic levels,” said R Ramakumar, economist and professor at the Centre for Study of Developing Economies, School of Development Studies at Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Social Sciences. “Even if there is a recovery in rural jobs to pre-pandemic levels, it indicates only that the slump of the pandemic is past us, but the real challenges, such as raising female labour force participation rate, are long term tasks.”

While a recovery from the very low pandemic-period levels is inevitable, the question to ask is whether we have reached pre-pandemic levels of rural employment, he said. “And remember that pre-pandemic levels already showed very poor levels of labour force participation.”

In January 2020, just pre-pandemic, rural employment rate according to CMIE data was 42%. It was 38.4% in April 2022. The labour force participation rate in rural India according to CMIE was 44% in January 2020 and was 41% in April 2022.

This is true for male labour force participation in rural India (73% to 68.3% in the same period) and for female labour force participation in rural India (12% to 10.7% in the same period).

“These are still nowhere near the pre-pandemic levels if we consider employment rates by CMIE,” said Ramakumar, whose February 2022 paper on India's agricultural economy argued that the pandemic had hit a rural economy that was already in considerable distress and that the overall high growth rate in agriculture did not accurately reflect the downward drifts in the economics of agriculture, the rising costs of cultivation, supply chain disruptions, price crashes, shrinking of credit and rural households' adaptive measures including lower consumption.

Rather than stressing on data of government procurement of commodities to indicate rural economic recovery, he said rural incomes are a better indicator. “If you look at rural incomes, there is a whole narrative built on more procurement and so on, but what is happening to cost of production, and hence profitability?”

Unorganised Sector Bears Brunt

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), considered a powerful driver of economies around the world, employed more than 11.10 crore people as per the National Sample Survey Report on unincorporated, non-agricultural enterprises (73rd round, 2015-16). In a written reply to Rajya Sabha in August 2021, union minister for MSMEs Narayan Rane said these businesses’ share in all-India gross domestic product (GDP) for the years 2018-19 and 2019-20 were 30.5% and 30% respectively.

Accounting for nearly a third of India’s GDP, the sector suffered a devastating meltdown during the pandemic and lockdowns, said the parliamentary standing committee on labour in its August 2021 report to Lok Sabha, particularly concerned as MSMEs employed 85% to 90% of Indian workers.

“The committee’s attention has been drawn to the fact that more than 81 percent MSMEs are self-financed with only around 7% borrowing from formal financial institutions and government sources,” the report said.

In Varanasi, this meant that weaver households that owned tiny units with two or three looms were as badly hit by the pandemic as wage workers, losing capital goods.

Khan, the Varanasi-based researcher who was field coordinator for CJP’s report on Purvanchal’s looms, told Article 14, “Loom bik gaye hain (there was distress sale of looms).”

Among the 204 families they surveyed, 77% of handloom operators and 80% of power loom operators had shut down — there was no work. Handlooms and power looms were both put up for sale even though these fetched a pittance.

They found power looms worth tens of thousands sold forcibly by landlords to collect pending rent and power bills, looms sold as scrap, one for as little Rs 23 per kg of metal. Nearly 85% of the respondents had borrowed money for survival. Those who employed kaarigars (artisans) could no longer do so, more weavers and artisans were trying to find odd jobs in shops, on day wages, selling tea.

Additionally, 4% of the surveyed weavers had no work at all after the lockdown.

While the CMIE survey would track these weavers/ artisans as employed on days that they sold tea or found a day’s wages, in interviews to CJP’s 17-member survey team these formerly self-employed artisans and job-creators said they were sitting idle most days, there was no productive work. These people were once gainfully employed through the year in design-making, spooling yarn, preparing the warp threads on looms, dyeing, weaving, zari work, embroidering or embossing stones on fabric, etc.

In urban commercial hubs too, self-employed service providers continued to weather the impact of the slow recovery.

In central Mumbai’s commercial hub of Dadar-Lower Parel-Worli, real estate broker Santosh Mane used to meet clients every day, mostly youngsters working in the banking, finance, technology services sector and looking for shared rental homes. “Rental agreements are down 50% in the Dadar area,” he said, adding higher fuel costs rendered everything dearer, taking the sheen off the low-paying jobs available in the locality.

“A chain of people is dependent on a good jobs market in the offices around,” he said, “such as owners of rental units, tiffin suppliers catering to bachelors in shared flats, delivery personnel, transporters, vendors of raw material, women working as domestic help or cooks in these rental units.” According to Mane, a grave under-employment runs through this chain.

Public Sector Employment Shrinks

In a pre-election promise, then union minister for railways Piyush Goyal said in January 2019 that the railways, one of the world’s top 10 biggest employers, would recruit 400,000 people over the next two years.

Instead, in January 2022, protests erupted across Bihar and parts of Uttar Pradesh against delays and changes to the procedure for selection of recruits from among those who had taken exams to qualify for various categories of posts.

Nayar, 23, who uses only a single name and belongs to a non-creamy layer backward class group in Bihar, had been living in Patna since 2019, preparing for entrance exams held for recruitment to various government jobs including, chiefly, the Railway. “I’d been preparing for three years and appearing for exams,” Nayar, a graduate, told Article 14. “Bas, ek job chahiye tha. (I just wanted a job.)”

Like tens of thousands of others, Nayar spent Rs 2,000 per month for a single bed in a grungy Patna building to attend coaching classes for these exams. Fees ranged from Rs 3,000 to Rs 8,000 for a single course in math, reasoning, general knowledge, current affairs, science. Most students took several courses, Nayar said, adding that education in Bihar’s rural areas was poor enough that degree-holders still required the coaching.

Those who returned to Patna to resume coaching classes after the second wave of the pandemic in 2021 often had no money for food. “We spent days surviving on just water, or one pot of khichdi for a roomful of students,” Nayar said. “Just in the hope of getting one of those 4 lakh new Railway jobs.”

In the January round of exam results, over 24 million aspirants had applied for 0.138 million jobs on offer. As results were released, it was apparent that some aspirants had been found qualified for more than one job category, an outcome that skewed the equation further, leading to angry protests by students already enraged at delays, confusion in cut-offs and changes in procedures.

Railway tracks were blocked at various places, leading to scuffles between police and protestors. In Gaya, empty coaches of a train were torched. Four hundred unidentified protestors and a handful of teachers from the coaching institutes were booked.

Some of these students’ families had sold plots of land or borrowed money to send them to Patna for coaching to get recruited to government jobs, said Nayar. Finding employment with the Railways was a cherished dream for almost all youngsters of his age, he said.

“Dare hue, thake hue bachhe hain (we are scared, weary kids),” he said. “We spent three years waiting to see if we can get a government job.” He was uncertain if he would return to Jamui, his home district, 180 km southeast of Patna, or if he would stay in Patna pursuing his dream.

Public sector employment in India has declined since 1994, show data from the ministry of labour and employment.

The public sector enterprises (PSE) survey for 2019-20 (the most recent available) conducted by the department of public enterprises under the union ministry of finance said central PSEs across sectors employed 14,73,810 persons in 2019-20 as compared to 16,24,114 in 2018-19, a reduction of 1,50,304 or 9% of its staff in one year.

The report added that the reduction in number of employees “was offset” to some degree by an increase in the number of casual workers. The data showed a 72% rise in casual workers or ‘daily rate’ workers between 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Precarious Work: Quality Of Employment Slips

In December 2021, about 11,000 aspirants queued up in the historic city of Gwalior, in the heart of Madhya Pradesh. There were 15 government jobs on offer, for peons, drivers and watchmen. Among the aspirants were young men holding degrees and postgraduate degrees in law, business, science and engineering.

Such underemployment was only one aspect of the post-pandemic worsening of employment quality. In its State Of Working India 2021 report on one year of the pandemic, the Azim Premji University’s Center for Sustainable Employment found that only 42% of workers in permanent, salaried employment in the pre-pandemic period (September-December 2019) continued to have the same arrangement in September-December 2020. While 29% moved to self-employment, 8% transitioned to salaried but temporary work, and another 8% began to work for casual wages.

“Precarity in jobs has reached a new level since the pandemic,” said Chandan Kumar of the Working People’s Coalition, a network of organisations working on issues related to informal labour. With formal jobs shrinking in the private as well as public sector, there is a huge labour surplus in the informal labour market, he said.

Wage growth rates had slowed down significantly pre-pandemic for casual as well as regular workers. In the post-pandemic months, these workers told volunteers and unions that there was extreme fear of losing jobs to men willing to work for less.

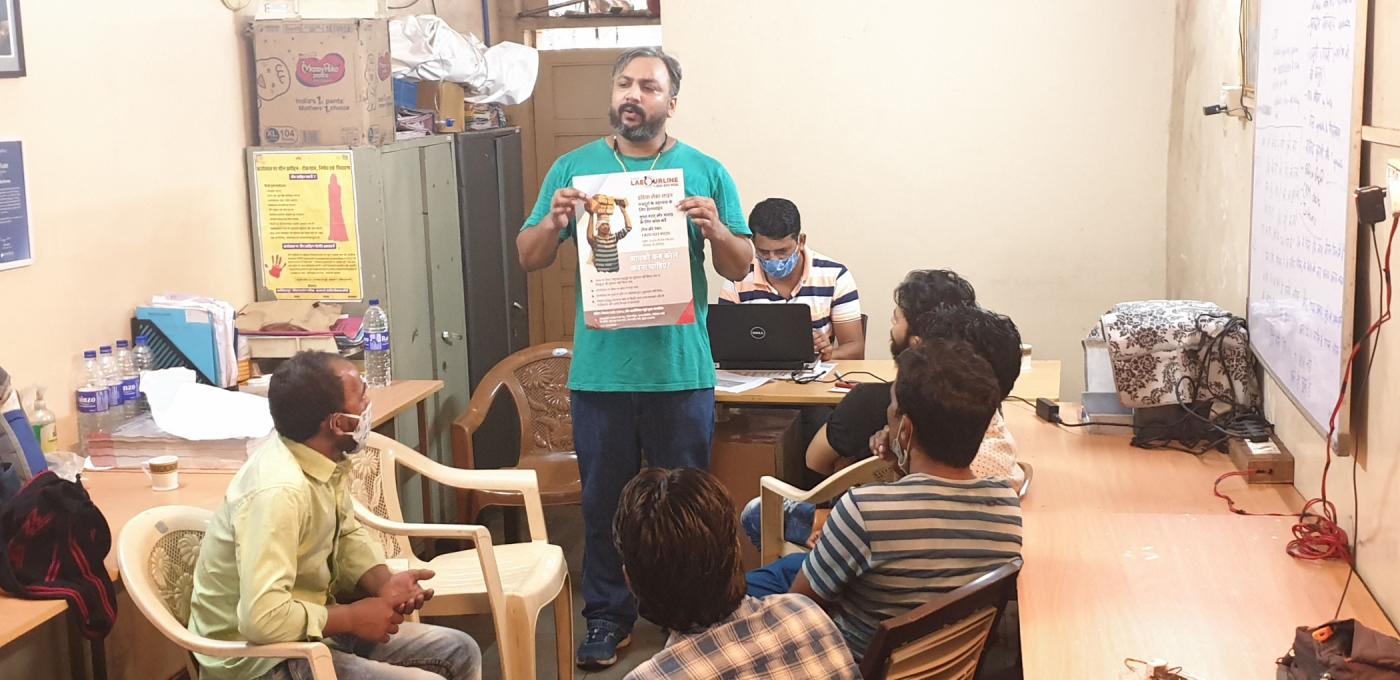

At ‘India Labourline’, a helpline for workers set up in the aftermath of the Covid-19 lockdowns by the Working People’s Coalition and Aajeevika Bureau, many callers were unwilling to register formal complaints about not getting minimum wages or wage disputes for fear of summary dismissals. “In the automobile sector for example, they earn only Rs 9,000 a month after working for 10-15 years,” said Chandan Kumar. “Now they’re terrified that if they complain about working conditions they can be replaced overnight.”

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/05-May/13-Fri/poster%20for%20Labourline.jpg]]

Unions and groups working for domestic workers, sex workers, street-vendors, recyclers, head-loaders, handcart operators, etc have said they were unable to regain pre-pandemic levels of employment. Even in the more developed states with higher employment rates, jobs with social security benefits, income satisfaction, training opportunities, etc were more difficult to regain post-pandemic.

Alongside, a large part of the workforce suffered reduced earnings, and consequently a reduced ability to pay for normal consumption levels. “There are two aspects to employment—whether there is work, and whether workers are earning enough,” said Srivastava of the Institute for Human Development.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/05-May/13-Fri/Informal%20workers.jpg]]In the informal sector, the tiniest units such as the thelawallahs (street vendors) could resume business post-pandemic as they required little capital to restart operations. Data about them does not show up in high levels of unemployment, said Srivastava, but in the form of low incomes. “Even those who continued to work during the pandemic have suffered a decline in real incomes.”

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14. She is the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss: The Story Of An Indian Drought’, a book on agricultural distress.)