Bandipora, Jammu & Kashmir: On a chilly 20 December morning in 2022, a frail labourer called Sanaullah Bhat, 60, left home with his national identification and bank account details, age certificate and ration card.

The government of the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) required Bhat and thousands of other pensioners, differently abled, widows and transgender people to submit these details to verify their credentials: that they were who they said they were and that they had these documents as proof, with most of them linked to Aadhar, the national identification database.

Once submitted and accepted, all of them would get or continue to get welfare payments meant for men above 60 and women above 55, widows or divorcees above 40, those with more than 40% disability and transgender people, for whom there is no age limit, with incomes below the poverty line.

The original pension programme began in 1995.

After standing in a queue for an hour to submit his documents and biometrics (fingerprints and retina scans) for verification at the government’s social welfare office in north Kashmir's Bandipora district, Bhat’s fragile body weakened, and he collapsed in the queue, a sheaf of papers in his hand.

Bhat was taken to a hospital where he was declared “brought dead”. His death made headlines, and it was criticised by regional political parties. His family got no help, only visits by officials.

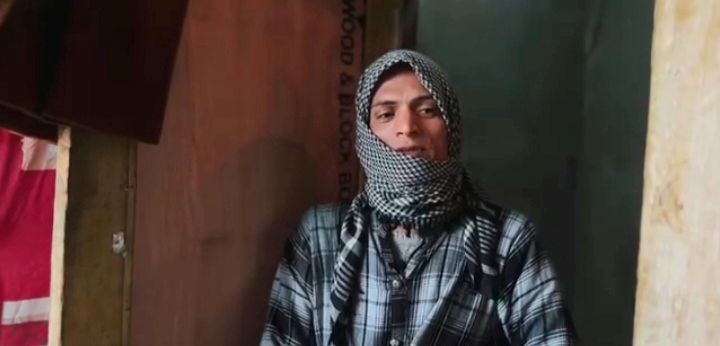

Bhat’s older daughter, Snobar, told Article 14 that the family heard on social media that a pensioner had died at the social welfare office in Bandipora.

"We never thought it would be our father,” she said.

“We were informed over a phone call by other pensioners about his death,” said Snobar. “My father's death was declared a cardiac arrest, but it was an attempt by the authorities to hide the government's failure.”

From Mangalam village in this northern district of J&K, Bhat, was the sole breadwinner of his family. His old-age pension of Rs 1,000 per month was a lifeline for his two daughters and wife.

"When the social welfare department started working online, hundreds of pensioners' payments were stuck due to a technical fault,” said Snobar. “Our father was one of them.”

Bhat's death was confirmed by the Bandipora hospital. Mushtaq Ahmed, the medical superintendent of Bandipora hospital told the newspaper Greater Kashmir that the cause of death was cardiopulmonary arrest.

‘Heartbreaking & Ruthless’

Bhat’s death and the travails of those who lined up to confirm their identities in J&K were the latest in a series of snags in online payments of government benefits nationwide.

Numerous problems have been reported with social-security programmes, including payments to women heads of families, child benefits, and subsidised food. Some were also reportedly dying after they were denied rations because of glitches with Aadhar.

“Since the system breaks down the various data silos and funnels the biometric and demographic data of over a billion people into one centralized database, this bulky mechanism creates numerous opportunities for error—some of them deadly,” Reetika Khera, a professor and development economist at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, wrote in The Washington Post in 2018.

Mohamad Yousuf Tarigami of the J&K Community party, expressed his concern over Bhat’s death, whose story we described earlier.

Former chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Mehbooba Mufti, posted a video on Facebook of pensioners, primarily in the 70s and 80s, waiting in long queues to submit their documents.

These documents include proof of age, confirmed by local chief medical or block officers; income certificate issued by a tehsildar; ration card; and proof from the civil supplies department that the beneficiary’s income is below the poverty line.

She said it was “inhuman” that the lieutenant governor was forcing senior citizens and disabled people to physically submit their documents for verification.

“This is leading to unwarranted inconvenience and hardship,” said Mufti. “Simply heartbreaking & ruthless.”

On 25 October 2023, J&K lieutenant governor Manoj Sinha lauded senior citizens while inaugurating a pensioners sammelan or meeting.

"Elders’ blessings are always priceless,” said Sinha. “J&K administration will ensure they live a happy and healthy life.”

From 15 Months, No Respite For Pensioners

On 8 September 2022, the department of social welfare moved the pension payment process online to verify pensioner accounts.

But many elderly pensioners, handicapped people, widows, and transgenders in Kashmir have found it hard to enrol online, without which they cannot now receive the monthly financial aid of Rs 1,000.

The government updates the records every five years, removing those who have died and adding new eligible ones. This year, as that process moved online, the complications grew.

Thousands of beneficiaries, especially the elderly and the disabled, waited hours outside government-designated centres in the cold to submit their documents for verification.

They believed that if they did not register online, their pensions would be revoked, which could happen technically but has not yet.

People in groups of 70 to 80 frequently traveled long distances and made multiple trips to get Aadhar data, age certificates and bank details from community centres designated to update documentation online. Those who live in rural areas had it worse.

Bhat’s family said he visited the social welfare office the day before his death and returned without submitting his papers, after standing for the entire day in a queue. He went again the next day and died in the queue, waiting his turn.

"The media carried multiple stories on us but we received nothing,” said his daughter Snobar. “It has been more than nine months. We are at God's mercy.”

Snober criticised the struggles that the elderly, transgender, widowed, divorced, crippled, and other impoverished people had to face to register online for their payments.

New Guidelines

An important change made to the pension process in 2023 was that every eligible person would get a pension or continue to receive one only submitting all documentation.

Data accessed by Article 14 shows that the social welfare department in Kashmir had received more than half a million (502,794) pension applications for pensions till 15 October 2023.

Of these, 3,686 were under process. As many as 380,413 were verified and 118,467 rejected. Some reasons for rejection include a failure to scan fingerprints and snags in linking documents to the Aadhar database.

In 2018, there were 200,000 pensioners. Now there are 380,000 pensioners who were not government servants. “In 2015, the government increased the pension amount to Rs 1,000 a month from Rs 200-Rs 300 earlier,” said Ashraf Ahmed, deputy director of the social welfare department.

He acknowledged that soon after the department moved the pension process online, there was “a gap” in payments since many beneficiaries “took a lot of time to upload their documents on the website”.

Some beneficiaries took time collecting the required documents, said Ahmed, and district officials helped those who had problems with a fingerprint or a retina scan.

The Travails Of Farooq Ahmed Mir

Farooq Ahmed Mir, 62, is illiterate and handicapped from birth, his left hand more useful than his left. Every day, he begs for a living in Srinagar’s Lal Chowk, the main square.

Fifteen years ago, Mir could not find a bride, he said, because of his physical condition. In 2008, he finally married Safina Begum, 29, from Uttar Pradesh, one of many brides brought from outside in Kashmir because many men cannot find a match locally, as Article 14 reported in 2022.

They have three children, 13,11 and seven. Mir lives in Sringar in rented accommodation and returns home to the village of Kralpora in Kupwara, 99 km northwest of Srinagar, two to three times a month.

"My family depends on my begging,” said Mir, who has received no pension for eight months. “My old-age pension was stopped due to the online verification.”

After it moved online, Mir’s Aadhaar was not linked to his pension account for months, and he took time getting a disability certificate.

When the social welfare department started the online verification of old age pensioners in September 2022, Mir visited a government-designated center in Kupwara’s main square to update his documents online.

His application was rejected: his fingerprints did not match the government’s record.

"How can my fingerprints match?” said Mir. “My right hand is fully bent. There should be a separate board that can help handicapped old-age pensioners.

Mir, who hoped his children would do better than he did in life, said he viewed the Rs 1,000 welfare payment as a critical additional income, which could help move them from a government private school where “they can get quality education”.

“But I have no source of money except begging.” His wife said he earned Rs 3,000 from begging, not enough to get by.

In May 2023, Mir submitted his documentation again, but there was no sign of the pension when this story was published.

These welfare payments are now regarded, in any case, as inadequate.

The president of Jammu and Kashmir Handicapped Association, Abdul Rashid Bhat, told Article 14 that the union territory’s administration led by lieutenant governor Manoj Sinha had not considered their request to raise the monthly pension from Rs 1,000 to Rs 5,000.

“We have protested many times,” Bhat said.

Simran Jan & Her Long Wait

Mohammad Yousuf, 36, a Srinagar-based transgender woman, popularly known as Simran Jan, complained of the government’s online enrollment for old-age pension.

From Srinagar's Habba kadal area, Simran Jan’s expertise has been matchmaking. She has also been a mehandi artist for decades. For about 13 years, Yosuf lived alone in a rented house in Srinagar.

"There is no employment when it comes to the transgender community in Kashmir,” said Simran Jan. “The monthly Rs 1,000 from the social welfare department serves as a lifeline for us in difficult times,” she said.

In 2019, transgender people were eligible to apply for government pensions. The main source of income for most was matchmaking, recently threatened with the emergence of social media.

“At least people like us can meet our basic needs with Rs 1,000," said Simran Jan.

Simran Jan saved Rs 13 lakh from her matchmaking to buy a two-storied old Srinagar house, where she now lives. On 21 March 2023, the house was damaged when an earthquake, with an epicenter in Afghanistan, struck Kashmir.

She sought but did not receive government help. An appeal for help on Facebook got her Rs 33,000.

With social media killing her matchmaking profession, Simran Jan applied seven months ago for the pension, as the government welfare payments are popularly called.

She had not earlier applied because the application process was too onerous, she said, requiring her to submit a domicile certificate, proof of residence, certificate of transgender identity, Aadhar card, ration card, copy of first page of her bank pass book, and an affidavit from a magistrate that she was not receiving any other government payment,

It’s been seven months since Simran Jan did all this.

"I have submitted all my documents,” said Simran Jan. “But I haven’t yet got my pension.”

"Whenever my phone beeps,” she said, “I check my messages to see if the pension has been credited to my account.”

(Irshad Hussain and Mubashir Naik are independent journalists based in J&K.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.