“In this committee, therefore, we begin our work today with a determination and a desire to come to decisions not by majority but by uniformity. Let us sink all our differences and look to one and one interest only, which is the interest of all of us—the interest of India as a whole”

Sardar Vallabhai Patel, 27 February 1947

Chennai: ‘No impediments to marriages between citizens shall be based merely upon difference of religion.’

This was the clause being discussed by the Sub Committee on Fundamental Rights in March 1947. Minoo Masani, a Parsi socialist elected from Bombay, was the proposer of this clause and was supported by his colleagues Hansa Mehta, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur and Dr B R Ambedkar. They were deep in discussion on the civil rights that would be a part of India’s new Constitution.

Unfortunately, Masani’s proposal lost by a narrow margin (5-4) and the fundamental right of choosing one’s own partner did not make it to the draft Constitution, which was debated in the full Constituent Assembly.

An opportunity to guarantee, and make justiciable, the right to choose a partner and marry freely was lost.

The Sub Committee on Fundamental Rights had been given the task of discussing and drafting the first version of the fundamental rights for the Indian Constitution. Members were aware of the important role that guaranteeing fundamental rights would play in a socially and economically unequal society and in fostering a common national identity.

Members of the committee agreed that merely articulating the fundamental rights without ensuring their enforceability would have limited meaning.

The members had several background documents to guide them in this endeavour.

They were guided by the work of the Constitutional Advisor, B N Rau, who had spent much of 1946 reviewing the constitutional texts of the world and was working on a draft constitution to be submitted to the Drafting Committee.

In addition to the notes from the Constitutional Advisor, several members of the committee had submitted their own drafts. This included:

a note on fundamental rights from noted economist and socialist, K T Shah;

a note on fundamental rights by legal doyen and member of the Drafting Committee, Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar;

notes and draft articles on fundamental rights from K M Munshi, who was an activist, politician and later became a founding member of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad;

a memorandum and draft articles on the rights of states and minorities submitted by the chairman of the drafting committee, Dr. B R Ambedkar.

Munshi’s draft was taken as the base document and was examined in conjunction with the other drafts submitted to the committee. Members of the sub-committee came with different perspectives and priorities.

For instance, Singh’s draft fundamental rights focussed on the protection of language and sub-national rights, with a special focus on the Punjabi language and people.

Ambedkar’s draft focussed on the social and economic inequity of the caste system and suggested the use of tools, such as separate settlements, to foster greater equity in the new nation.

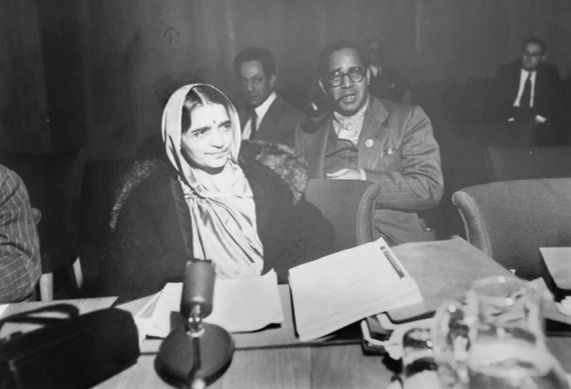

Also, on the sub-committee were two leading feminist voices: Hansa Mehta and Rajkumari Amrit Kaur. Both of them were past Presidents of the All India Women's Conference (AIWC) and fierce advocates for gender equality.

Mehta was a lifelong advocate of women’s empowerment. Along with Eleanor Roosevelt, she served as co-chair of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights Committee. She is attributed with changing Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to reflect “all human beings” as opposed to “all men”.

Kaur was a freedom fighter and gender equality champion. She co-founded the AIWC in 1927 and went on to become health minister and independent India’s first female cabinet minister. She was instrumental in setting up the All India Institute for Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

In 1946, headed by Mehta, the AIWC had submitted a draft of Indian Women’s Charter of Rights and Duties. The charter had several progressive demands, including universal adult franchise, recognition of domestic labour of women, equal property rights and the right to marry freely, without restrictions on the basis of religion or caste.

On 28 March 1947, the important issue of interfaith marriage came up for discussion in the sub-committee. At the time, interfaith marriage in India required participants to either denounce their faith (the Special Marriage Act III, 1872) or register their marriage outside India.

Marriages under the Special Marriage Act, 1872 required a written notice to the concerned Registrar and a 14-day waiting period. There was no provision for registration of marriages between individuals professing different faiths.

Sitting that day were nine members of the sub-committee: Acharya Kripalani, Ayyar, Kaur, Mehta, Ambedkar, M R Masani, Shah, Munshi and J Daulatram.

Singh and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad were not in attendance.

Earlier in the day, Minoo Masani had brought up a proposal to include a uniform civil code which would be applicable to all Indian citizens.

This was rejected by a slim majority (5-4). The majority were of the opinion that this was outside the scope of the fundamental rights.

The clause on the uniform civil code was later included in the Directive Principles, and even this inclusion created much furore in the Constituent Assembly. The debates supporting and criticising the UCC today are echoes of the debates in the Assembly.

Undaunted by the earlier loss, Minoo Masani proposed a clause based on Article 54 of the Swiss Constitution*: ‘No impediments to marriages between citizens shall be based merely upon difference of religion’

The committee was split along familiar lines, and the motion was rejected in a 5-4 vote. In favour of the proposal were Masani, Kaur, Mehta and Ambedkar.

In their note of dissent, Masani, Kaur and Mehta expressed their regret that this right did not make it to the draft Constitution, stating that such impediments did not sit well with claims of a common nationhood and urged the members to include it:

“Such an impediment to marriage between two Indians is a reflection on our claim to common nationhood. Only as recently as February 26, 1947 , Mahatma Gandhi is reported at a prayer meeting to have supported the idea of marriages between persons professing different religious faiths, each retaining his or her own religion without abatement. Unfortunately, such marriages cannot be solemnized in India today.”

While the uniform civil code was discussed in detail in the Constituent Assembly, the clause on interfaith marriage was forgotten. The Special Marriage Act (1954) did ease some of the restrictions on interfaith marriage, but the simple and fundamental right sought by Masani and others remained unfulfilled.

*Authors Note: The right to marry and have a family is guaranteed as a fundamental right under Article 14 of the current Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation (of 18 April, 1999).

(Shruti V is the founder of The Equals Project and a graduate of the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru. The Equals Project aims to democratise access to constitutional history and values through workshops for children and young adults, teaching Constitution creation through experiential learning. Learn more about them on their Instagram page.)