Bengaluru: For the first time in years, five-year-old Geluvu slept peacefully through the night of 18 December 2021, without jail alarms waking him up in the wee hours. After a struggle of nearly two-and-a-half years, his parents had managed to have him sent home from the Parappana Agrahara jail in Bengaluru, to his father Shivu, 37, a surrendered Naxal who also went by the alias Jnanadev.

As he prepared to leave, the boy distributed candies to the jail warden. "I will be going to school soon," Geluvu announced, before Shivu took him out for an orange-juice treat.

Geluvu lived in jail with his mother Kanyakumari, an undertrial. A former Naxal, Kanyakumari, 36, surrendered in June 2017 when Geluvu was six months old. Since March 2020 when the Covid-19 outbreak began, Shivu’s only contact with his wife and son was over phone calls or a rare meeting in a courtroom or a hospital.

On 18 December, Geluvu was finally sent home to Shivu, almost 30 months after the parents began to petition the courts and jail authorities, and more than a month after the district Child Welfare Committee (CWC) ordered the jail authorities to do so.

Kanyakumari, who hails from Jarimane in the Mudigere block of Chikkamagaluru in western Karnataka, was an active member of the Save Kudremukh campaign, protesting the eviction of tribal families from the Kudremukh national park in Chikkamagaluru.

Encouraged by Naxals who had given up arms and were being rehabilitated through a 2010 state government scheme, Kanyakumari, Shivu and an associate named Chinnama surrendered before the Chikkamagaluru district administration, in the presence of members of a state-appointed panel, which included journalist Gauri Lankesh who was killed by Hindutva group later that year and lawyer A K Subbaiah, a former Jana Sangh member and Karnataka’s first state president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 1980.

Four years later, the couple said they are struggling to hold the State to promises its representatives made.

Their hopes for an enhanced cash award and assistance in raising their boy, discussed with the government-appointed committee at the time of their surrender, are dimming.

Sensitive rehabilitation schemes by states are a key element of multi-pronged programmes to counter left wing extremism, approved by the ministry of home affairs, with guidelines for providing to surrendered cadres an immediate grant, a stipend, facilities for vocational training and separate cash incentives for surrender of weapons.

Some states have reported a drop in left-wing extremist activity partly on account of attractive surrender and rehabilitation packages, including Odisha and Maharashtra.

But Shivu and Kanyakumari’s experience has been one of inadequate monitoring of their rehabilitation and absence of vocational training or livelihood support for Shivu, and the compulsion of a legal battle in order to raise their child as they wish.

Shivu is a daily wage worker at a powerloom factory at Bannerghatta in Bengaluru. He works overtime to make ends meet and afford legal expenses.

Senior lawyer V Suresh, PhD, also general secretary of the People’s Union For Civil Liberties, said that in many circumstances, people take up radical activities out of compulsion, and when the government extends an amnesty scheme offering to drop cases against them, there is a responsibility on the government to respect the commitment.

Suresh, who practises in the Madras High Court, said the government's failure to fulfil the promise is a betrayal of the trust of “ordinary people from very marginalised backgrounds”, an act that would dissuade others who may otherwise consider amnesty schemes in the future.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2021/12-December/21-Tue/ChildSurrenderedNaxals1.jpg]]

Rethinking Life As An Underground Activist

Kanyakumari’s sister Yashoda, also a Naxal, was wounded in a firefight between police and Maoists in 2003 near Idu village in Udupi district. Yashoda was arrested in November that year and would spend the next 10 years in jail.

Deeply affected by police harassment following her sister’s arrest, Kanyakumari decided to join the Naxal movement, Shivu told Article 14.

But a bullet injury to her neck during an encounter with police in 2009 led her to give up active work, though she remained underground because there were two cases against her at the time.

Kanyakumari and Shivu married in February 2016, and Geluvu was born in January 2017. But Kanyakumari’s poor health and the uncertainty about her son’s future made her rethink life as an underground activist.

The members of the state-appointed panel accompanied the surrendering Naxals to the Chikkamagaluru office of the deputy commissioner, also the district magistrate. "The superintendent of police of Chikkamagaluru and the deputy commissioner presented us in front of the media and announced that our rehabilitation program would begin soon,” Shivu said.

Shivu and Chinnama were released upon surrender, but Kanyakumari, who had 33 cases against her in various police stations, was taken into custody and later sent to the Parappana Agrahara jail, also called Bangalore central jail. On her request, the court agreed to let her keep Geluvu, then six months old, with her in prison.

‘How Can A Jailer Decide The Welfare Of A Child?’

According to Shivu, his lawyer Shantaram Shetty submitted the couple’s first request for the child to be sent to the father’s home in 2019, to a lower court in Udupi. They were directed to file their application in the Chikkamagaluru court. By then, a nationwide lockdown had been imposed and Shivu could not approach the court.

“I approached jail authorities through my lawyer. They replied that nothing can be done without a proper order,” he told Article 14.

Through 2020 and 2021, Shivu and Kanyakumari picked their way through legal procedures to request the state to release their son from prison.

Geluvu was not ill-treated in prison, Shivu said, but he did not want his child to “grow up in a jail atmosphere”. He said: “I want my child to grow up normally in society without the restriction of those prison walls.”

In April 2021, Shivu filed an affidavit before the Chikkamagaluru district and sessions court demanding custody of his child, with Kanyakumari’s consent, the couple in agreement that the boy would now fare better living with his father. They initially filed the petition in an Udupi court, but were later directed to approach the Chikkamagaluru sessions court.

Laxman Gowda, their lawyer, said their main argument was that the child was now aged five years and 10 months and had the right to education. “So we requested the jail authorities to hand over the custody of the child to his father,” Gowda said.

The court passed an order on 20 April 2021 stating that the child appeared to have been born to Kanyakumari while in custody. “On perusal of records of trial court and of this court, there is no order with respect to the custody of the child with accused, till date,” the order said. “Therefore there is no need to pass order by this (sic) regard.”

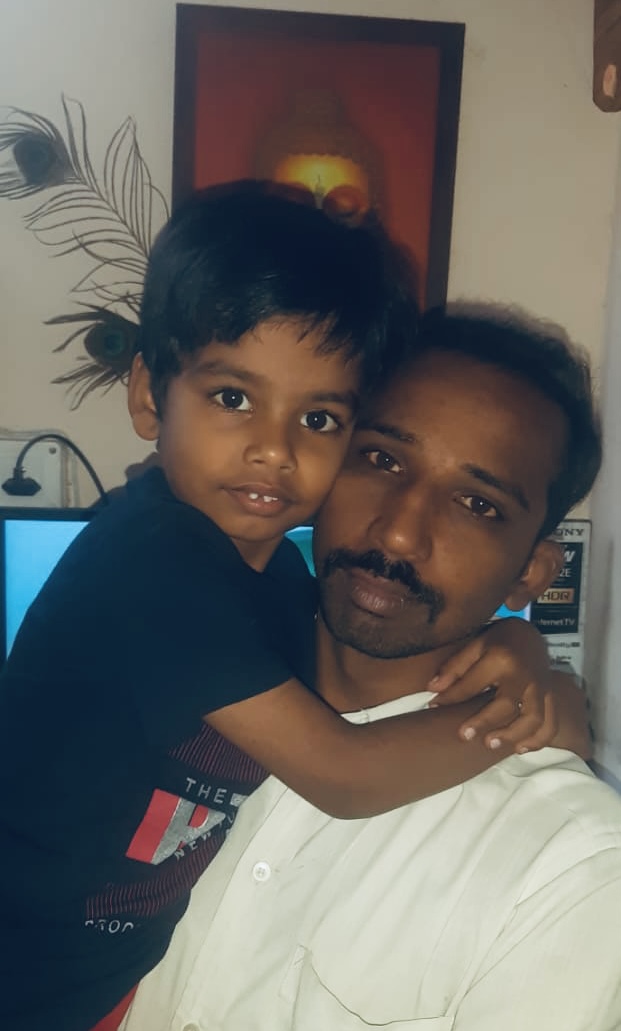

Multiple media reports from the day of Kanyakumari’s surrender, however, showed a photograph of the child on his father’s lap.

The court order directed jail authorities to act as per the jail manual. There was no immediate response from the jail.

“A child up to six years of age shall be admitted to the prison with his mother if no other arrangements, for keeping him with relatives or otherwise, can be made,” says the prison manual.

In this case, the child’s biological father was ready to take over active guardianship of the child, a move supported by the mother.

As the jail authorities refused to send the child back, Shivu filed a complaint with the child welfare committee (CWC), the competent authority under the Juvenile Justice (Care And Protection of Children) Act, 2015, called the JJ Act.

According to senior lawyer S Balan, jail authorities should have had no say in where the child should live. “The paramount consideration by the law will be where the child's interest can be safeguarded,” said Balan, questioning how jailers can decide the welfare of a child. “Who are they to do so?”

On 10 November, the CWC wrote to the Parappana Agrahara jail superintendent instructing that the child be sent home as he was five years old and had the right to an education. The mother has no objection, the CWC letter pointed out, adding that Kanyakumari should be allowed to meet Geluvu in jail twice a month.

According to Shivu, the jail authorities told him the CWC later was forwarded to senior officials, and a response awaited. The child would be sent home, if officials raised no objections.

Finally, on 18 December, Geluvu was home, Shivu said. The couple is less hopeful of the state keeping other promises it made at the time of their surrender.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2021/12-December/21-Tue/ChildSurrenderedNaxals2.jpg]]

A Child In Prison During A Pandemic

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Shivu would visit his wife and child in jail once a week. He would carry chocolates, food, clothes, toys and colouring books. Shivu also had special permission from the prison superintendent to meet the child in the latter’s office.

Before Geluvu returned home, Shivu last met his wife and son at a court hearing in Kochi on 8 July 2021.

Initially, the prison lacked a proper facility for the child. “He was lodged in a cell with many prisoners around and lacked nutritious food,” said Noor Sridhar, a former Maoist who surrendered in 2014.

The family and activists had to approach the jail authorities through a lawyer to demanded better facilities for the child. One prisoner even threatened to go on a hunger strike until Geluvu received better facilities. The superintendent agreed to Kanyakumari’s demands, according to Sridhar.

On 30 October, Article 14 sought comment from the jail superintendent over a phone call with detailed queries about facilities provided for undertrial prisoners’ children. He requested to be called back, but remained unavailable subsequently.

Journalist Sukanya Shantha, part of the Amnesty International team that visited Bangalore central jail in 2016 as part of a research project on children of undertrial prisons, said the balwadi (nursery school) for children was not functioning systematically at the time.

Also, it was located inside the prison compound, violating the model prison manual for the superintendence and management of prisons in India, which clearly states that the creche and nursery school shall be “run by the prison administration preferably outside the prison”.

“The teachers did not come to the nursery school on a regular basis,” said Sukanya. “There were a couple of NGOs working with the nursery school and they were doing some recreational stuff but all of it was haphazardly done,” she said.

Alone, Incarcerated And Isolated During Lockdown

The lockdown took a toll on Kanyakumari's mental state, and she felt alone and abandoned for months as Shivu’s visits had to be suspended.

“There was nobody to listen to her and console her,” Shivu said. “There are limitations to video calls. Nothing can replace the warmth offered by a meeting in person.” Kanyakumari would call Shivu on video call every Thursday. She would let him know if they needed anything, which he would then try to send by courier.

In poor health when she surrendered, Kanyakumari finally underwent surgery for an old bullet injury in her neck in the first week of December, at Bangalore’s Victoria Hospital. “She told me there is some relief from the neck pain,” Shivu said.

But Geluvu is underweight, appearing to have received poor nutrition over the years. Shivu plans to take the boy to a doctor next week.

Mainstreaming Rebels: How Karnataka’s Policy Evolved

In 2010, the BJP-led Karnataka government unveiled a policy for the rehabilitation of left-wing extremists in the state who surrendered.

The surrender policy was to be implemented by district committees headed by the deputy commissioner (also the district magistrate) and with the superintendent of police as convenor. The chief executive officer of the zilla panchayat (called zilla parishad elsewhere in India), the district social welfare officer, and a member of a grassroots civil society organisation were to be on the committees.

Every surrender would be further approved by a state-level committee whose members included the home secretary, the director general of police (DGP), an inspector general (IG) and the state intelligence chief. This committee’s convener would be the deputy inspector general (DIG) of the anti-Naxal force.

The district committee was to discuss the eligibility of each surrendering person and cases against him or her. The proposal would then be forwarded to the state committee for approval.

The policy offered compensation up to Rs 200,000, a monthly stipend of Rs 2,000 for vocational skills training, land grants and additional incentives for surrender of weapons.

Civil Society Efforts To Assist Surrendering Maoists

When the Congress government of chief minister Siddaramaiah took office in 2013, the Citizens Initiative for Peace (CIP), a civil society group that negotiated for peace between Naxals and the state, asked the government to ease Maoist surrenders by modifying the policy. Lankesh, Subbaiah and freedom fighter H S Doreswamy were among the CIP members.

Meanwhile, at a press conference in December 2013, a splinter group of Naxalites, including Sridhar (also known as Noor Zulfikar) and Sirimane Nagaraj who had broken away from the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in 2005 over ideological differences regarding armed resistance, expressed their willingness to continue their struggle democratically.

“The CIP actively negotiated on behalf of us with the Siddaramaiah government,” said Sridhar, who surrendered in 2014.

In September 2014, the Karnataka state government revised the surrender and rehabilitation policy and, for the first time, included civil society members in the state-level committee. Lankesh, Doreswamy and Subbaiah were included as civilian representatives.

Taking into consideration the suggestions of civil society members, the new policy increased the compensation, almost doubling it.

In December 2014, Sridhar and Nagaraj surrendered before the Chikkamagaluru district authorities. Doreswamy garlanded the duo.

The BJP, in opposition in Karnataka, alleged that the surrender was in fact a conspiracy to recruit more people for the Maoists’ armed struggle. They branded Lankesh as a Naxal sympathiser and demanded that she be removed from the committee.

Sridhar spent at least 40 days in jail, in connection with four cases against him, two each in Chikkamagaluru and Udupi, in which he was eventually acquitted four years later.

According to Shiv Sundar, a member of the CIP and a columnist for Gauri Lankesh Patrike, the weekly edited by Lankesh, the committee was initially very active, meeting once every three or four months, or whenever a Naxal expressed interest in approaching the committee.

According to Sridhar, Kanyakumari and Shivu approached him in 2015, seeking to surrender and accept the compensation money—the mother and son both needed medical attention. Sridhar put them in touch with the civil society members of the resettlement committee.

A few months before Kanyakumari’s surrender, H V Vasu, a doctor and an activist, went to a secret location to meet Kanyakumari. Vasu told Article 14 that he found Kanyakumari suffering from anaemia and back pain.

“She had a bullet injury on her neck, and she lacked proper nutritious food,” said Vasu. “Her child was suffering from malnutrition.”

The doctor and other civil society members convinced her that she could avail regular treatment if she surrendered.

“Kanyakumari’s main demand while surrendering was that the Karnataka government should not oppose her bail… and will not register new cases against her,” said Sridhar. “Her second demand was regarding the rehabilitation package.”

After her surrender, Kanyakumari wrote a letter to the government asking for a higher compensation.

The committee took notice of it and proposed an enhanced package, a suggestion accepted in 2018, though the bureaucrats were of the view that Kanyakumari could only receive the old package because the revised policy was introduced after her surrender. “The government also promised orally that they would take care of the child’s wellbeing,” Sridhar said.

The 33 cases against Kanyakumari in police stations across the state were under various sections of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), 1967 and various sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, the Indian Arms Act, 1959, The Explosives Substances Act, 1908, and Prevention of Destruction and Loss of property Act, 1984.

There are 15 cases registered in Chikkamagaluru district, 17 in Udupi, and one case in Shimoga district.

There were also 24 cases against her registered by the Kerala Police under UAPA, IPC, Arms Act and the Kerala Forest Act, 1961. This included 11 cases in Wayanad district, five each in Malappuram and Palakkad, two cases in Ernakulam and one case in Kannur district.

The cases against Kanyakumari pertain to taking up arms against the state, distributing pamphlets for the Maoists, disturbing public peace, possession of weapons, and threatening people. “Most of the complainants are public servants. Many cases lack strong eyewitnesses,” said Laxman Gowda, the lawyer who appeared for Kanyakumari in Chikkamagaluru.

So far, Kanyakumari has been acquitted in five cases, and not yet convicted in any.

One case was registered by the Kochi office of the country’s top anti-terror body, the National Investigation Agency (NIA). This case pertained to an incident in Vellamunda of Wayanad district on 24 April 2014, in which five people armed with AK-47 rifles barged into the house of A B Pramod, who worked with the civil police, and threatened to kill him if he did not resign and stop helping anti-Maoist operations by the police.

Kanyakumari's name was added to this case after her surrender, notwithstanding her condition that fresh cases would not be registered against her.

No Mention Of Cases In Another State

Advocate Tushar Nirmal Sarathi who is representing Kanyakumari’s co- accused in the Vellamunda NIA case, said that she had said at the time of her surrender that she was not actively involved in Naxal activities on account of her poor health.

“There is a tendency by the state to include the name of the people from Kudremukh belt in any Maoist-related case. Kerala Police also resorted to a similar pattern with a justification that there are Karnataka Maoist cadres active in the Western Ghats region,” Sarathi said. Kanyakumari has said that she was included as an accused in the Vellamunda case even though she had no information about the incident.

“Another injustice is that Kanyakumari was given the chargesheet in Malayalam,” Sarathi said. It took days to translate the chargesheet from Malayalam to Kannada.

Also, at the time of her surrender, the list of cases given to Kanyakumari only mentioned cases registered in Karnataka. “There was no mention of cases in Kerala. So even if she gets acquitted in all the cases registered in Karnataka, she might have to spend years in jail due to the cases in Kerala,” the lawyer said. The surrendering Naxal couple had not been told of this.

Waning Role Of Civil Society In Rehabilitation

Activists said Gauri Lankesh’s murder in 2017 also slowed down the process of resettlement of Naxals. Subbiah and Doresamy, who also led the process of resettlement wholeheartedly, are now dead too, passing away in 2019 and 2021 respectively.

In early 2019, the then BJP-JDS government initiated a new committee including professor J B Shivaraju and lawyer Govind Raj.

Shivaraju told Article 14 that they attended a meeting headed by chief secretary Vijay Bhaskar and attended by other members of the committee in February 2019. “We proposed to the government to double the benefits for the Naxals who were ready to surrender,” he said, adding that Bhaskar agreed in principle but the government delayed passing such an order.

The lawyers were also not granted permission to meet those who had surrendered earlier. “So we thought there is no point in keeping a committee for namesake, so we resigned,” said Shivaraju. During their six-month tenure in the committee, it met only once.

Earning A Living Wage As A Former Naxal

Livelihood for the surrendered Naxal couple has been a challenge. Wary about taking up a job offered by the police, Shivu found employment at a powerloom factory in Bannerghatta, Bengaluru.

“I get Rs 300- Rs 350 rupees for one sari. It takes eight hours to manufacture one sari,” Shivu told Article 14. “I try to make at least two saris a day.” He has a debt of Rs 350,000.

Kanyakumari received Rs 2.5 lakh as compensation from the state, but that money was spent on lawyer fees and case-related expenses, Shivu said. A daily wage labourer, he works at least 16 hours a day.

Shiv Sundar said that the regime change in 2018 also affected the resettlement process. “The ruling BJP government is not interested in humanitarian treatment of Naxals. Rather they prefer to show a repressive face,” he said.

Sundar said the Naxals’ demand is legitimate and humane, and “within the constitutional framework”. He said the Naxals being forced to remain underground means the circle of bloodshed will continue.

(Ashfaque E J is an independent journalist based in Kerala.)