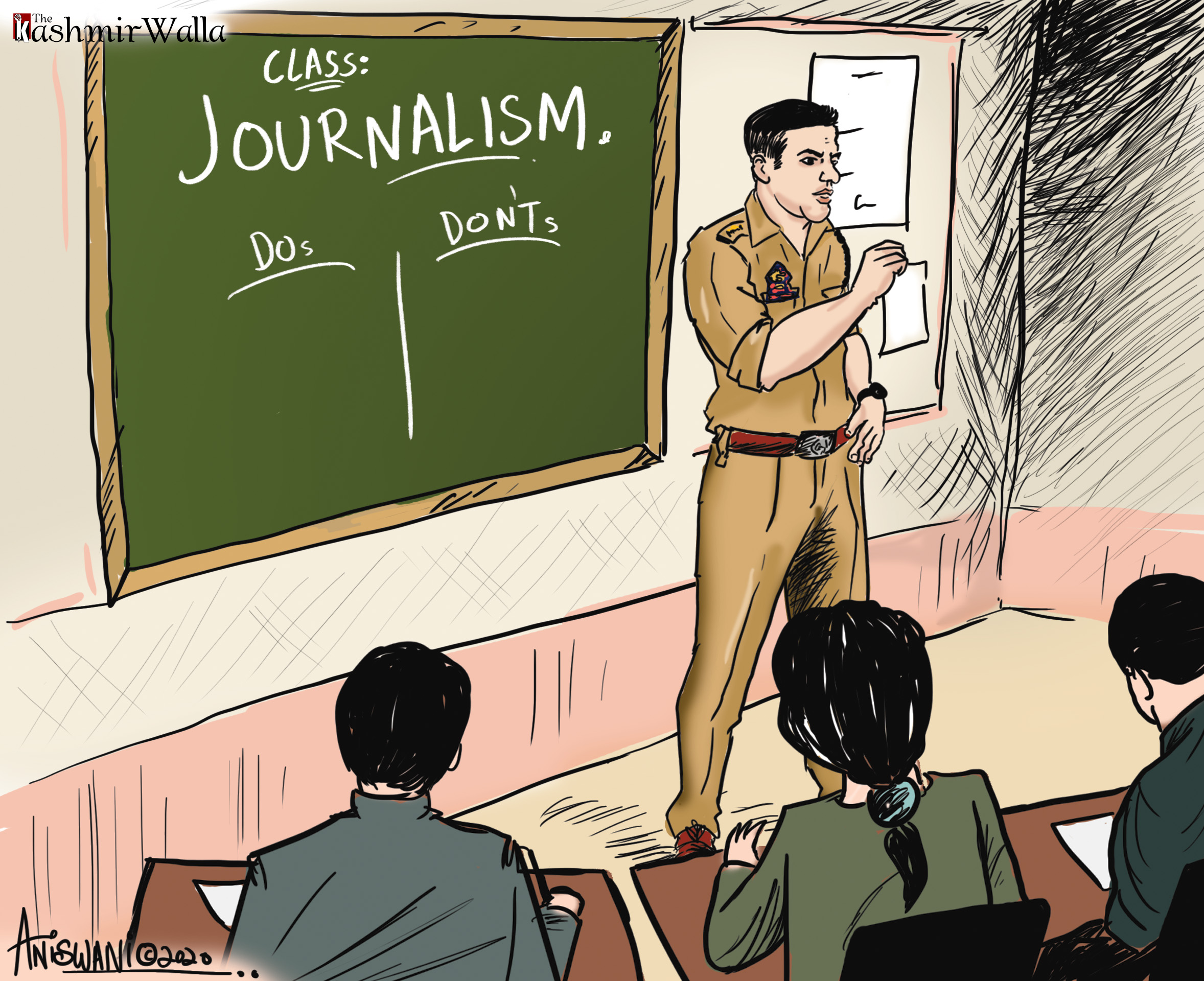

Srinagar: It is meant, as the government of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) puts it, “for effective communication and public outreach”, but a new 53-page media policy released on 2 June 2020 abounds in diktats and threats against the media.

Some examples:

“There shall be no release of advertisements to any media which incite or intend to incite violence, question sovereignty and integrity of India or violate the accepted norms of public decency and behaviour.”

“Any individual or group indulging in fake news, unethical or anti-national activities or plagiarism shall be de-empanelled (shorn of official recognition and access) besides being proceeded against under the law.”

These are some of the vague phrases and undefined terms that the J&K government made official as part of a document called ‘Media Policy 2020’, issued by J&K’s Directorate of Information and Public Relations (DIPR).

Police cases against journalists for writing news stories and social-media posts preceded the new media policy, intensifying a chilling effect on the media in one of the world’s most militarised areas. The policy also goes against India’s constitution, said critics.

“The policy is undemocratic and goes against the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression,” said Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor of Kashmir Times, an 56-year-old English daily, one of J&K’s oldest.

“It is unfortunate that J&K’s information department, which has no expertise and authority, will now act as a watchdog on (sic) the press, and they get to decide what is fake news and what is anti-national,” said Bhasin. “There are no criteria, and things are not defined.”

On 27 June, Article 14 sought comments through phone calls and texts from J&K’s Director of Information and Public Information Syed Sehrish government spokesperson and Principal Secretary (power and information) Rohit Kansal. There was no response to the day this story was published. We will update this article if and when they respond.

“It is clear that the administration wants to give policy cover to muzzle the press in Kashmir,” said Muzamil Jaleel, deputy editor with the Indian Express in Delhi. He said these rules did not exist in any Indian state, and the new policy was intended to justify cases filed this year under anti-terror and other laws and keep up pressure on journalists by frequently questioning them.

Aliya Iftikhar, senior Asia researcher at the Community to Protect Journalists, (CPJ), a global advocacy based in New York, said the CPJ was “very concerned” by the media policy’s views on fake news.

The CPJ has documented (here, here and here) how fake-news laws around the world are abused by governments in efforts to curb critical reporting. Given the Indian government's track record in targeting journalists critical of its policies with legal and criminal cases, particularly in Kashmir, it was “hard to believe” the policy would not be misused, said Iftikhar.

“We urge the Jammu and Kashmir administration to show good faith toward the media community and press freedom and to immediately withdraw this policy,” said Iftikhar.

Crackdown Preceded New Media Policy

Bhasin’s view on the chilling effect of the new media policy was echoed by many media representatives in the Valley, sparking particular disquiet because it was preceded by a government crackdown on journalists.

When 26-year-old photojournalist Masrat Zehra faced charges under the anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, on 18 April for “anti-national” posts on social media—she posted photos and comments of her work—in April, it scared many in the media.

On 21 April, the J&K police filed first information reports against (FIRs) journalist and author Gowhar Geelani for “indulging in unlawful activities” and “glorifying terrorism in Kashmir” through social media posts and the Hindu‘s Kashmir correspondent Peerzada Ashiq for publishing “fake news”.

“If you see the contents of recent FIRs against journalists in Kashmir, they are extremely vague and don’t mention anything incriminating [or that can] qualify as being a cognizable offence,” said Salih Pirzada, who represents Geelani and practices at the Jammu and Kashmir High Court.

“The FIR (against Geelani) vaguely mentions that the person is misusing social media, which causes disaffection against the State,” said Pirzad. “By that logic any person who is in disagreement with the government can cause such ‘disaffection’ and are hence liable to be punished under the UAPA.”

Filing cases against and summoning journalists to police stations is not particularly new in a restive province, but the frequency and intensity with which journalists have been summoned and harassed has increased since 5 August 2019. That was when the government of India removed Article 370—a constitutional provision that accorded special status to J&K—and split the former state into two union territories.

The new media policy is seen by critics as carrying forward and legitimising the pressure applied to J&K’s media since then. Freelance journalist Rayan Naqash said journalists were “sidelined” and “non-native journalists flown in” to provide a “different coverage” of the lockdown and accompanying communications restrictions (which continue after six months as low-bandwidth mobile data services) that followed the abrogation of article 370.

“To me, the language used in the policy and its general direction suggests it to be somewhat a counterinsurgency SOP (standard operating practice) for the media, simultaneously alluding to wrongdoings by journalists,” said Naqash.

“The summons, intimidation and harassment was being done earlier,” said Bhasin, who on 10 August filed a petition against the communications blackout before the Supreme Court, which on 11 May refused to restore 4G Internet and referred the issue to a government committee). “But now it (harassment) will be done in a systematic, structured and organised manner.”

The Power Of Security Clearances

The new media policy requires mandatory background checks of newspaper publishers, editors and key staff members before “empanelling”—or making them eligible for—government advertisements or according to them other official recognition.

This is particularly relevant because newspapers in Kashmir, in the general absence of commercial advertising depend in large measure on revenues from government advertisements.

Punishment and retributive actions against newspapers accused of publishing so-called objectionable content, said Parvez Imroz, an award-winning human-rights lawyer, will adversely impact human-rights monitoring in the region.

“This policy will hit our work if the media stops reporting on human rights issues,” said Imroz.

The policy has made security clearance of a journalist mandatory before awarding accreditation, official recognition that allows access to government news materials and access to its agencies.

Ashiq of The Hindu argued that the silence of newspaper editors in Kashmir over the policy indicated the control that the government already has over the media, especially after 5 August.

“There is a cost if you speak out,” said Ashiq, who was summoned twice by the police after the FIR was registered against him. “So people don’t want to speak out because they don't want to pay the cost.”

Ashiq said “the policy is aimed to put an end to any kind of inconvenient journalism in Kashmir”.

Since 5 August, local media in Kashmir rarely contradicted the government narrative or questioned its decisions, said observers.

Haroon Rashid, editor of Urdu daily Nida-e-Mashriq, said the reason for this silence was the summoning of two editors—Fayaz Kaloo, Editor-in-Chief of Greater Kashmir and Haji Hayat Mohammad Bhat owner and Editor-in-Chief of Kashmir Reader—by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) and the banning of advertisements (later restored) to their newspapers.

“These incidents set a precedent and a tone,” said Rashid. “Many journalists thought, if the editor of the prominent Greater Kashmir wasn’t spared, how will others be?”

On 18 June the Kashmir Editors Guild (KEG) intended to discuss the new media policy during a meeting of office-bearers, who are editors of prominent Kashmiri newspapers.

“It was made clear to all the members that the meeting was not backed by the KEG but (by) editors of the news dailies. But out of over a dozen members, only five attended,” said a member of KEG, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Nobody discussed anything, and the meeting was called off, and as a result, there was no stand against the policy.”

Against India’s Constitution

The new media policy violates constitutional provisions for freedom of the press and free speech, said legal experts, who pointed to existing laws to check fake news.

There are sufficient penal laws—such as sections 124A and 153A of the IPC—to check publications that incite violence or disharmony, said Vrinda Grower, a lawyer who represented Bhasin of the Kashmir Times in the Supreme Court petition we referred to earlier.

“Ironically, the media policy emphasizes the promotion of online media while the government has repeatedly curtailed (by slowing) the internet to low-speed 2G rather than 4G speed,” said Grover.

Pirzada, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court lawyer, said the media policy masqueraded as an instrument that accorded arbitrary power to the police. He referred to The People’s Union for Civil Liberties vs the Government of India and another, 1996, which forbade unauthorised telephone taps, which were freely being used by the police.

“It (the telephone tapping case) was found to be violative of the fundamental right to privacy,” said Pirzada. “And the Supreme Court laid guidelines for exceptional situations which might lead to the requirement of phone tapping.”

(Auqib Javeed is a Srinagar-based journalist.)