Srinagar: Large parts of the internet have been restored in Kashmir, but that isn’t going to bring back the 50,000 Instagram followers of entrepreneur and designer Iqra Ahmed.

Iqra started to wear pherans that she had designed while she was still a student pursuing a masters degree in Linguistics at the University of Kashmir. The traditional Kashmiri dress made her the talk of her varsity and, so, it seemed natural that after completing her degree she would set up an online business, Tul Palav (roughly, ‘take clothes’) in November 2015 in order to ‘preserve Kashmir’s unique culture and tradition’.

Tul Pulav, said Iqra, is one of the first of its kind online clothing stores out of Kashmir. But years of hard work unspooled on 5 August, 2019 with an internet ban following the Narendra Modi-led government’s decision to scrap Article 370 that provided special status to Jammu and Kashmir.

The lifting of the seven-month internet and social media ban in Kashmir--the longest recorded in any democracy—on 4 March has meant little to Iqra as internet speed is sluggish since cellular networks continue to run on 2G. Moreover, social media sites like Instagram, on which Iqra would display her latest designs and get new orders, remain off limits.

On 18 January, there was a partial lift on internet services in the state with limited access to 300 websites, though the ban on social media remained. A few days later Iqra’s account on Instagram vanished. She said she has lodged a complaint with the Cyber Cell department, but so far there is no news on when, if ever, her account will be restored.

A Costly Ban

The internet ban has devastated the state’s economy, crushing businesses, entrepreneurs, handicrafts and tourism.

These sectors are the backbone of the state’s economy and losses have run well over a billion dollars, or Rs 7,100 crore, according to the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) ever since the Centre revoked its autonomy and statehood in August last year.

But particularly hard hit are women entrepreneurs, many of them running small businesses or first-time entrepreneurs reliant on high-speed internet to transact business.

“As Kashmiris, we are used to such conditions and I thought things would be okay in a few days. But with each passing day it became clear that things would not only be different but tougher,” said Iqra, who did a fashion designing course from Delhi in 2017.

Iqra has worked extensively to preserve tila, aari, and sozini—types of traditional embroidery. She not only helped bring the pheren back into trend by giving it a modern look but also took to the international market by collaborating with models from outside Kashmir.

This was possible due to technology, social media and the internet.

The internet blockade impacted her business and prevented her from reaching out to customers, Iqra said. Her team of four workers have been out of work, and with the loss of her Instagram account, she will have to rebuild her business and customer base virtually from scratch.

“After every internet ban in the past, I would work hard to cover up my losses but this time it seems impossible. Summer is the prime season for weddings in Kashmir and every bride requires two to three pherans for her new closet but that season is completely lost," Iqra said.

Other women entrepreneurs who depend on the internet to transact their businesses have also been affected. Beenish Qayoom, who lives in Srinagar had collaborated with her friend Omaira for an online outlet called Craft World Kashmir (CWK) that sold crochet products such as floral jewelry for brides, dresses for children, warm socks and hand-made caps.

The idea was, they said, to revive and preserve traditional crochet work. The orders came after people started appreciating their designs—their Instagram page has more than 49,000 followers—and they were receiving up to five orders a day, they say, when internet services were snapped.

“Even now without high speed mobile internet, we are not able to access Instagram and reach out to our customers,” said Omaira.

“Over 20-30% of our orders come from outside Kashmir, 70% from within the state. If social media remains slow and out of reach then how will our business run?” said Beenish. “We either have to look for jobs or move out of the state. Neither possibility is feasible right now.”

Morale Is Also Down

The seven-month internet ban not only impacted business but also morale.

CWK had trained 14 young women from underprivileged families to produce its designs, but these women have been out of work. “I was trained by Craft World Kashmir and later opted to work with them as a team member,” said Saima Jan, one of the 14 women. “They can provide me with work only if they get orders. For the past seven months they have not received even a single order," she said. Prior to the ban, CWK used to receive up to five orders a day.

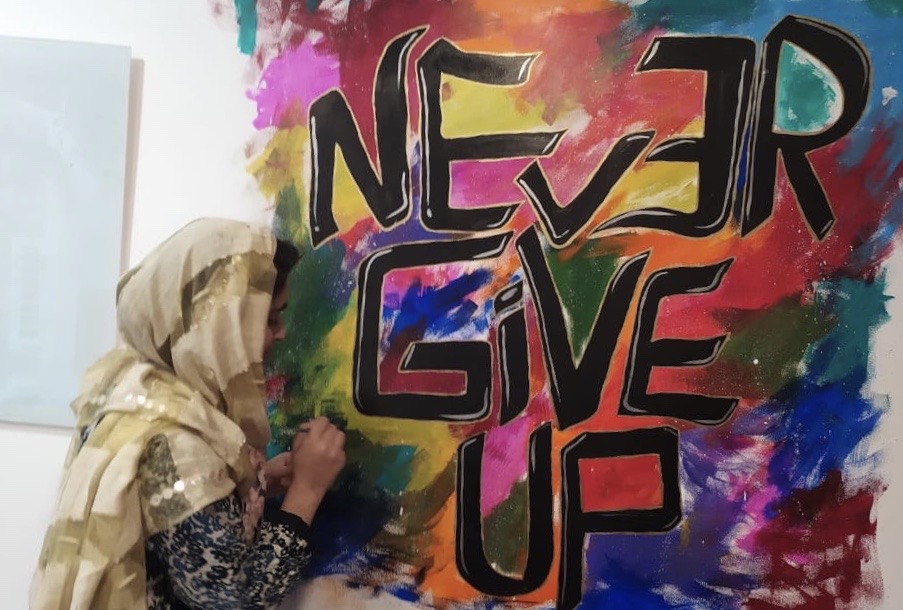

Shafiya Shafi, a freelance artist with a preference for abstract work, too relies on Instagram to promote her work. With 4G mobile internet yet to be restored, she said, lifting the ban is of no help to her. “If I have to upload a picture on Instagram, how will I do that?”

Shafiya’s Instagram handle, Shafiya_artworks, which she set up two years ago, had over 1,500 followers and, she said, she would receive commissioned orders after posting photographs of her paintings online.

Prior to the ban, Shafiya received orders for seven to eight portraits every month, charging anywhere between Rs 1,000 and Rs 3,000 depending on the detail and size. In addition, she said, she also received two to three orders a month to hand-paint walls, charging between Rs 30,000 and Rs 35,000 per commission.

There were no walls to paint or portraits to draw after the communication blackout.

“Even now, without high-speed internet, I can’t receive orders. I’m at the stage of my career where I need a lot of online marketing. People had only just begun to notice my art. I had started to create a name for myself but that name has died with the internet ban," said Shafiya.

‘Out Of Our Hands’

The only entrepreneurship development institute in the Kashmir valley—Jammu Kashmir Entrepreneur Development Institute (JKEDI) has trained 30,000 youth and helped set up 15,000 units—about 85% of them internet-reliant. Each of the 15,000 units generated three to five jobs, on an average, engaging about 75,000 unemployed youth in the Valley, said G. M Dar, Director, JKEDI.

“We understand that entrepreneurs who depend on social media to operate their ventures have faced issues but this is out of our hands,” said Dar.

While everybody’s hurting, women have paid a particularly steep price in a state where female labour force participation at 10.6% is already far lower than the national average of 27.4% in 2015. A survey by JKEDI found that women-led 56.39% of entrepreneurship initiatives conducted by it in 2016. These projects had been approved by the department with financing by the banks. Of these initiatives, 22.15% were completely internet dependent as they are related to handicrafts and tourism sectors.

JKEDI’s Women Entrepreneurship Programme targeted women in the age group of 18-45 years with a minimum qualification of matriculation. It provided them with a direct loan facility of up to Rs three lakh at 6% rate of interest.

“Women and men both suffer in any condition but in business women have different challenges to face like financing, procurement of raw material and stiff competition from male counterparts as the primary role of women is still considered to take care of the family and men escape these challenges easily,” said JKEDI’s Dar.

Jammu and Kashmir has fared “poorly in generating jobs for its young population”, said the 2019 Unemployment in India report by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Young people constitute 60% of the state’s population. “The unemployment rate in the erstwhile state stood at 15.89% in the first four months of 2019, making it one of the worst performers on the job generation front,” noted the report.

But the valley has also suffered huge losses due to the internet shutdown, said Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) president Sheikh Ashiq Ahmed.

“The condition of big business houses is miserable as they have loans to repay and interest rates are high. The majority of businesses in Kashmir, IT, tourism, handicrafts and so on, are internet-based and for online entrepreneurs there is no alternative but to cope with the situation," Ahmed says. “Our young entrepreneurs have been completely jobless. This loss has already taken a toll on our economy and will take years to recover.”

The losses run into US$ one billion (Rs 7,100 crore), found a November 2019 report from the KCCI, which is completing a report estimating the losses of the past six months.

Kashmir valley is routinely stripped of internet connectivity but was sent into a complete communication and media blackout on August 5, 2019.

On 14 October, 71 days later, only post-paid mobile services (excluding SMS) were restored. After six months, 2G internet services were restored with limited access to 300 websites, excluding social media. After seven months, internet is back, but the losses continue.

(Safina Nabi is an independent reporter from Kashmir.)

Additional Reading:

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/india-top-court-declares-internet-a-fundamental-right/1699142#