Channagiri, Karnataka: “My husband was the sole breadwinner. Now, my life means nothing. I don’t know what lies ahead.”

Heena Banu was talking about her husband, Mohammad Adil, a 30-year-old carpenter, who on 24 May 2024, was detained by police in Channagiri, in Karnataka’s Davangere district, on charges of matka gambling, a local form of betting in which players place bets on a particular number from a range of available numbers.

He was never seen alive again.

Matka gambling is a non-cognisable offence, which means the police cannot make an arrest without a warrant or a magistrate’s permission under the Karnataka Police Act, 1963.

There was no such warrant. Yet, as it often happens in India, he was arrested, and his family, unaware of his arrest, only learned of his death in police custody during a post-mortem later that night.

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID), Bengaluru, took over the inquiry into Adil’s death on 25 May 2024, as many media reported.

As of 24 December 2024—over seven months after the death—despite the suspension of two police officers by chief minister Siddaramaiah of the Congress party, the CID inquiry had not been concluded.

“There is no movement,” said Davangere Nizamuddin, district secretary of the Association for the Protection of Civil Rights (APCR), a non-governmental organisation that advocates for civil rights.

Seven months and a fortnight later, the CID’s investigation remains inconclusive. At the same time, Heena Banu has not received any compensation from the State, despite the family filing a complaint with the Karnataka State Human Rights Commission (SHRC).

The Supreme Court has awarded compensation to the next of kin of the deceased in some instances of custodial deaths. However, no uniform timeline has been stipulated for awarding such compensation.

In November 2024, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) ordered the government of Odisha to pay a compensation of Rs 500,000 to the next of kin of a man who allegedly died in police custody two years ago. The NHRC recommended that the compensation be disbursed within eight weeks.

Data show low compliance with compensation recommendations for custodial deaths. For instance, in 2019-20, the NHRC recommended compensation of Rs 12.32 crores in 437 cases, yet compliance reports were submitted for only 113 cases or no more than 25.8%.

Systemic Biases

According to a 2020 report by the National Campaign Against Torture, data from NHRC annual reports from 1996-97 to 2017-18 reveal that 71.58% of custodial deaths in India involved individuals from poor or marginalised backgrounds, with Muslims accounting for 14.7% of the cases.

The report defines “poor” as mainly coming “from the lower castes, known as the Dalits (scheduled castes), Adivasis (scheduled tribes) and religious minority groups, mainly Muslims”, stating that these vulnerable groups of India have borne the brunt of the criminal justice system's biases.

According to the 2022 Prison Statistics India report, of the 573,220 prisoners in India, 19.3% were Muslim, up 1.3 percentage points over the previous year.

Over a decade, more than one in six undertrials were Muslim, higher than the Muslim population share in India, according to the report.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2021 report, the latest available data, states that Muslims comprise over 30% of detainees despite forming only 14.2% of the total population of India.

“The systemic othering of Muslims has become deeply entrenched in our society, starkly reflected in law enforcement practices,” said Venkatesh Nayak, director of the Delhi-based Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative.

Nayak cited instances when the police engage in "rounding up” (randomly targeting groups based on identity), often targeting the Muslim community first, whether in the name of preventing mob violence or ahead of elections.

Nayak said that rising instances of caste and communal hate speech further dehumanise minority communities.

“Multiple National Police Commission reports and inquiry commissions, which probed incidents of communal violence, have pointed to the institutional bias against religious minorities, particularly Muslims," said Nayak.

Earlier this year, the Delhi High Court ordered the transfer of the probe into the death of 23-year-old Faizan, who was forced to sing the national anthem during the Northeast Delhi riots in 2020, from Delhi Police to the Central Bureau of Investigation. The court said that the police action amounted to a “hate crime”.

The NHRC recorded 275 deaths in police custody between April 2020 and March 2022, with 175 deaths recorded during 2020-2021 and 100 during 2021-2022.

The ministry of home affairs informed the Rajya Sabha in 2023 that over five years to March 2022, the highest number of custodial deaths were reported from Gujarat, at 80. This was followed by Maharashtra (76), Uttar Pradesh (41), Tamil Nadu (40), and Bihar (38).

“Custodial torture is the norm across police stations," said Mangla Verma, a lawyer practising in the high court and trial courts in Delhi. “Custodial death is an extreme form of custodial torture.”

The NHRC also highlighted 95 illustrative cases of custodial deaths from 1996-97 to 2017-18, with 68 victims from impoverished families and only 3.19% from middle-class backgrounds.

Both Nayak and Verma emphasised that “access to justice” became more difficult because the victims of custodial deaths came from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

Adil’s death has left his family financially vulnerable, with no State compensation seven months later, his case reflecting the lack of such support nationally.

Over five years to 2022, the NHRC recommended monetary compensation totalling Rs 28.47 crores in 1,184 custodial death cases, Factly, a data-journalism website, reported in November 2023.

Compliance remains low; in 2019-20, compliance reports—from public authorities, showing proof of payments recommended by the NHRC—were submitted for only 113 of 437 cases.

Appeals Fail

The APCR and members of Adil’s family complained to the Karnataka SHRC, urging a fair investigation by the CID, public disclosure of the post-mortem report, and Rs 15 lakh compensation with a government job for Heena Banu.

The first complaint was drafted on 25 May 2024, with three subsequent follow-up letters sent in the following months.

However, APCR’s Nizamuddin said that the Karnataka SHRC has failed to issue any such order for compensation until now, deferring the hearing date, originally from 11 November 2024 to 25 February 2025.

Both the NHRC and the SHRCs have the authority to direct state governments and police departments to provide compensation in cases of custodial deaths under the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993.

“The lack of clarity, response, and compensation also amounts to mental harassment,” Nizamuddin said.

Nizamuddin is part of a fact-finding team that includes members from the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), the APCR, Bahutva Karnataka, and the All India Lawyers Association for Justice.

“It is a trite law that justice delayed is justice denied,” the August 2024 fact-finding report said.

Article 20 of the Indian Constitution protects an accused person against arbitrary and excessive punishment.

Judicial Safeguards

The Supreme Court, in cases such as Neelabati Behara vs State of Orissa and Arnesh Kumar vs State of Bihar, has upheld Article 21 (the right to life and personal liberty) as a safeguard against illegal detention.

The fact-finding report cites Rudul Shah vs State of Bihar & ANR and Sebastian M. Hongray vs Union of India & Others as instances where the SC “awarded monetary compensations as a remedy in public law against violations of the State”.

In January 2024, the Supreme Court stayed a Meghalaya High Court ruling that mandated compensation of ₹10–15 lakhs to be paid by the State government in cases of custodial deaths.

A bench comprising Justices B R Gavai, Sanjay Karol, and Sandeep Mehta issued a notice on Meghalaya's appeal. It directed that the High Court's order remain stayed, provided the State pays compensation as determined by the NHRC.

The Meghalaya High Court had previously emphasised the need for substantial compensation, setting compensation amounts between ₹10–15 lakhs, to deter custodial violence, calling such incidents a “slur on civilised society”.

‘I Seek Justice’

“First and foremost, I seek justice,” said Heena Banu. “However, my children’s future looks bleak, and as a mother and grieving wife, I plead for state-sponsored education for my children.”

Heena Banu and her three children, one of whom recently fell ill, currently live at her parents’ rented accommodation. Her father, a daily wage earner, is the sole breadwinner.

Heena Banu’s ageing father said the increased expenses overburden him.

His parents and his two sisters also survive Adil. Adil’s parents were also dependent on his income.

On condition of anonymity, one of the locals told Article 14 that the children are now seen loitering from “bus stand to bus stand”.

Heena Banu has been grappling with physical and mental health challenges, from recurrent illnesses such as fever, cold, body aches, and insomnia.

Presently, Heena Banu said she is in a fragile state of mind and unable to work. “Mera khayal mujh mein bhi nahin hain (I am lost),” she said, describing her sense of loss and detachment.

Violation Of Arrest Protocols

“We were told that the police protect us,” she said. “Aisa kya galti kiya tha ki itni badi saza mili? (What mistake did he commit that he received such a heavy punishment?)”.

Heena Banu refers to the disproportionate punishment for the petty crime Adil committed.

The fact-finding report describes matka gambling as not a serious offence, warranting imprisonment of up to three months or a fine of up to ₹300.

According to the report, Adil was picked up by the police from near Latif Hotel in Channagiri’s Tippunagar between 7.00 and 8.45 pm, as per the account of witnesses.

However, this contradicts the FIR, which said he was taken into custody at “home.”

According to the testimony of the superintendent of police, Uma Prashanth, Adil collapsed at the Channagiri police station shortly after arrival, after which he was rushed to a government hospital but was declared dead upon arrival.

The time was 8:45-9:00 PM on 24 May.

A call from the police instructed Adil’s family to rush to the Davangere District Hospital, where the deceased’s body was taken for post-mortem at 2:00 AM on 25 May 2024.

That same day, his body was returned to the police station after the post-mortem at noon.

Once the family identified the body, a complaint of unnatural death was lodged by the family against the police officers.

A witness, who didn’t want to be identified, fearing for their safety, told Article 14, “When we (some of the people gathered at the Channagiri police station) asked what the post-mortem revealed, the CID did not disclose the information. However, CID Madam mentioned that Adil died owing to ‘low BP’”.

The said ‘CID Madam’ is Karnataka CID's deputy superintendent of police, B M Kanaka Lakshmi.

Lapses In Protocol

Adil’s arrest exposes glaring lapses in protocol.

Section 41 of the Criminal Procedure Code allows for arrests without a warrant for cognisable offences—serious crimes such as theft or assault—for which a police official may arrest without warrant. However, for less serious crimes (non-cognisable offences), they cannot arrest someone without first getting permission from a Magistrate.

However, in Karnataka, there’s a separate rule under Section 88 of the Karnataka Police Act that allows police to arrest someone without a warrant for certain petty crimes or non-cognisable offences, like public gaming. This creates a loophole since it seems to go against Section 41, which was exploited in this case.

However, the Karnataka High Court has clarified that Section 88 of the Karnataka Police Act does not convert a non-cognisable offence into a cognisable one, stressing the need for procedural adherence.

“Such an overlap or ‘loophole’ legitimised the arrest without a warrant; this is all the more important because the person died in custody,” said Aishwarya R., PUCL Karnataka, a civil rights organisation.

In Adil’s case—the DK Basu guidelines, which mandate arrest protocols to safeguard human rights—were blatantly disregarded.

In DK Basu vs. State of West Bengal, the Supreme Court held that the rights guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution could not be denied to convicts, under-trials, and other prisoners in custody, except according to the procedure established by law.

The SC laid down specific requirements and procedures, including allowing the person arrested, detained, or interrogated to inform a relative, friend, or well-wisher.

Adil was not afforded this right.

No Arrest Memo

In addition, no arrest memo was prepared, and no witness attestation or diary entry was made, as required by the guidelines laid out by the Supreme Court in 1997.

Furthermore, the case against Adil was registered only after his death.

“From securing Adil to the vehicle in which he was brought and his death at the police station, the entire process was ridden with flouting of procedural norms with no immediate steps taken by either the deputy superintendent of police or the superintendent of police,” said Aishwarya.

Pointing out discrepancies in the police’s account of “securing” Adil, Aishwarya asked, “Was he picked up or arrested? Was it detention or preventive arrest?”

Article 14 repeatedly contacted SP Uma Prashanth via phone calls and WhatsApp texts from 21 October to 5 November, seeking comment. A follow-up WhatsApp text was sent to her on 6 January 2025, informing her that the story was nearing its publication. There was no response.

This story will be updated should she respond.

Karnataka chief minister Siddaramaiah ordered the suspension of the deputy superintendent of police Prashanth Manavalli and police inspector Niranjan, while denying it was a “custodial death”, contrary to a fact-finding and other news reports indicated.

Data compiled from NCRB Crime in India reports, over two decades, from 2001 to 2020, showed 1,888 custodial deaths, with 893 cases being registered against police personnel, DW.com reported. The same report states that formal accusations were made against only 358 officers, resulting in no more than 26 convictions.

According to the Factly report, NCRB data indicated that police personnel have not been convicted of human rights violations since 2018. Verma, who is the convenor of Youth for Human Rights Documentation, a network focused on documenting and ensuring justice in cases of state violence and hate crimes, stressed the need for “police accountability”.

Aishwarya said, “The violation of protocols additionally leaves room for arbitrary threatening and extortion of bribes.”

Mass Protests To Mass Arrests

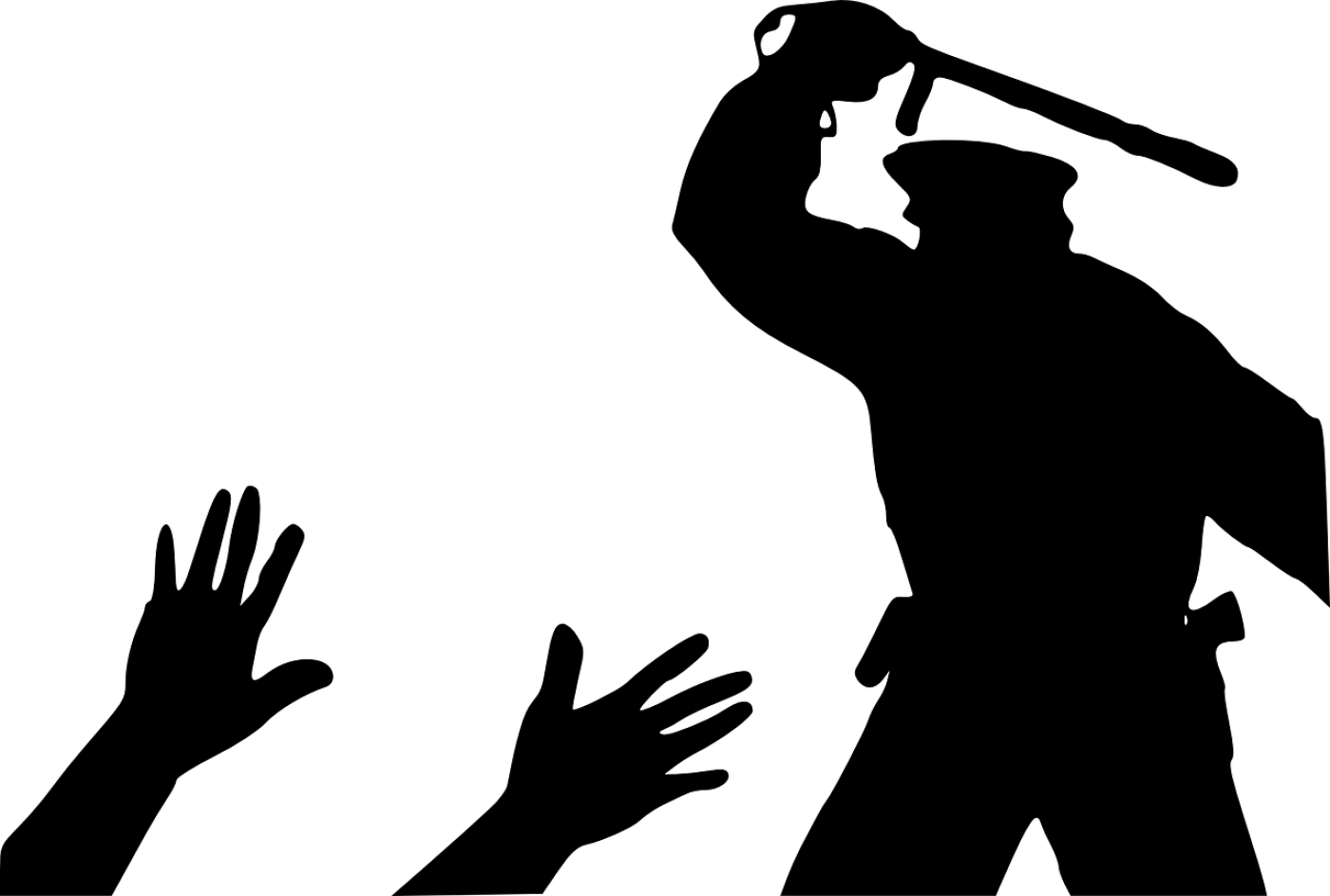

Following news of Adil's death, crowds gathered outside the police station. Police responded with rubber bullets and lathi charges, resulting in protestors allegedly throwing stones at police vehicles in retaliation.

In the aftermath, six first information reports (FIRs) were filed against approximately 300 individuals for unlawful assembly and rioting. By 25 May, 2024, around 47 people had been arrested.

“Those arrested spent one and a half months in jail,” said Davangere Nizamuddin, district secretary of APCR. “They are out on bail, but they and their family members continue to live on the edge, worrying any moment a chargesheet could be filed and they could be arrested, breaking their spirit.”

According to Channagiri-based social activists Mohammad Aftab and Afroz Khan, Afroz Ali Khan, a retired 12th class principal, and Haji Khuddus—a respected community elder and businessman—the reaction was a “spontaneous outpouring of anger and shock” from the community.

“A significant section of the protestors are working-class members,” Afroz said. He added that today, the dynamics between the police and Channagiri’s Muslim community, 38.07% of the town’s population of 21,313, exhibit “a severe breakdown of trust”.

“Arrest protocols were not followed; family members were not informed, vehicles were seized, and several complained of violence in custody,” said Aishwarya of PUCL.

“As an after-effect, especially after the Vishwa Hindu Parishad took out rallies to protest the protestors’ act, the image of the Muslim community took a hit, with members being painted as ‘trouble-makers’ or a ‘nuisance’,” another local, on condition of anonymity, told Article 14. “This, in effect, has set off a chain reaction of being ostracised amid rising hostility, for instance, with local businesses run by Muslims being shunned.”

As the day gave way to dusk, Heena Banu held up a photograph saved on her mobile—one of her wearing radiant pink and a broad smile, standing next to Adil.

“Survivors should not be viewed through the lens of pity but justice,” Heena Banu said. “The State has abandoned me and my children.”

(Sanhati Banerjee is an independent journalist and a content consultant.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.