Mumbai: Parmanand Jaywant Koli was a year old in 1985 when his father and 256 other families were asked to relinquish their lands in the hamlet of Koliwada, one part of a quiet, prosperous village called Sheva-Koliwada, 50 km south of Mumbai.

The government had chosen their mango and cashew orchards and fertile soil on Sheva island in Uran taluka of Maharashtra’s Raigad district as the site for the expansion of India's largest container port, the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT).

They were promised new homes 20 km southeast in the town of Uran, with basic amenities, such as a school, health centre, water, sanitation and a road.

After several months of negotiations with the government of Maharashtra, the 256 families agreed that year to move to a “transit camp” with crowded residential units and community toilets, which was supposed to be a temporary living arrangement.

It is now 2024, the 256 families have grown to 400, and Koli–like all of them– still lives in the transit camp, waiting for the rehabilitation that had been promised 39 years ago.

The villagers of Sheva-Koliwada rue how their lives changed: from lush, open countryside to a crowded transit camp, their farmlands and livelihoods lost. The ruins of the old village still exist.

Members of the fishing community revealed that their traditional means of livelihood is no longer a viable source of income. They have been forced to turn to other activities including salt and poultry farming. Many are daily wage labourers.

"My father waited for decades to be rehabilitated but died in the transit camp," said Koli, a former sarpanch, head of the village council, of Hanuman Koliwada, the transit camp where they now live.

"I'm 39 now, and there's no hope in sight,” said Koli. “I doubt I’ll see my community properly rehabilitated."

The irony: the JNPT never used the land the villagers gave up. The expansion to the port was built on reclaimed land.

Despite the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, and a 2017 Lokayukta order directing the JNPT to return the unutilized land to its original owners, that never happened.

"Apale rajya ani prashasan apalya lokanchya kalyanasathi katibadha, durdarshi ani paropkari netanchya abhavane trast ahe (Our state and administration lack visionary leaders committed to the welfare of their people)," Koli said in Marathi.

The promises that the government made of new homes, essential amenities, and living space were not realised.

Their one or two room houses made of exposed bricks and wood are dingy and cramped.

Only four public toilets were built for the 256 families to use. Recently two more, exclusively for women, were built as a part of corporate social responsibility projects.

Residents continue to contend with persistent infrastructure issues, such as termites causing structural damage to houses, a lack of a permanent approach road, proper drainage and a water pipeline.

On 21 November 2024, more than half the eligible voters of the transit camp boycotted state assembly elections, although party workers and officials tried to coerce them to vote, according to media reports (here and here).

Farmers No Longer

The fisherfolk in the settlement were forced to look for alternate employment because the creek nearby is polluted and cannot be used for fishing. They lack the space to process and dry the catch and said their former livelihood was no longer viable.

Those previously dependent on farming have experienced a complete loss of livelihood, since they no longer own land.

Some have found government jobs, but their lives as farmers, foragers and fishermen have ended.

During the monsoon months, from June to September, forest vegetables were available in abundance and the winter and summer seasons provided a bounty of cashew nuts, mangoes and other fruit.

The forests also supplied the village with ron nuts (ron mewa) and firewood and timber for their chulhas, traditional wood-burning stoves, for cooking.

There was enough water in the wells and lakes of Sheva-Koliwada for their homes and farms. Salt pans in the region provided additional employment. They said the land, sea and forest provided a livelihood through the year.

Encounter With The State

On 28 March 1971, the lives of those in Sheva Koliwada changed when the government of Maharashtra established the City Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO).

CIDCO acquired 2,933 hectares or 29 sq km of land—1169 hectares of private, mainly agricultural, land and 1,764 hectares of government land—from 12 villages and handed it over to Jawaharlal Nehru Port Authority (JNPA) for the first phase of the Jawaharlal Nehru Port.

In 1982, more Sheva and Koliwada village land—mostly residential—was acquired for the second phase expansion of the port project. The land was acquired under the Land Acquisition Act, 1894.

The Raigad collector’s office deemed 361 families from Sheva hamlet and 256 families from Koliwada hamlet eligible for rehabilitation and resettlement.

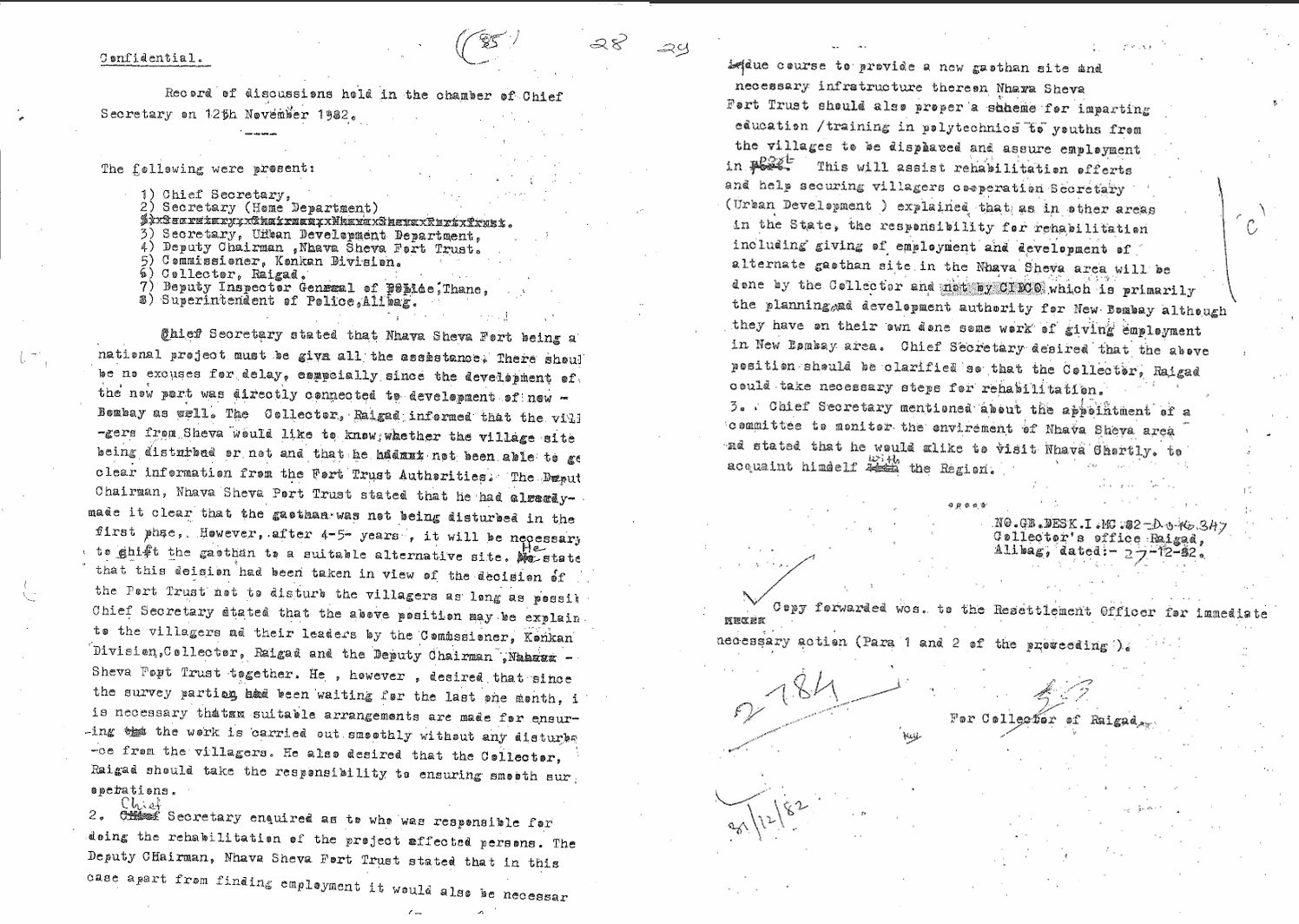

In a confidential letter dated 24 December 1982, the secretary of the urban development department of the Maharashtra government informed the collector of Raigad that his office was responsible for rehabilitating the families displaced by the JNPT project.

Following this, on 18 November 1983, the Maharashtra government formed a committee to oversee the rehabilitation work, led by the commissioner of the Konkan Division.

On 5 December 1983, the committee instructed the Raigad collector to allocate land to displaced families based on their agricultural status. following government regulations.

A 1983 government resolution applied the Maharashtra Resettlement of Project Displaced Persons Act, 1976, to Hanuman Koliwada camp.

By 21 June 1984, the commissioner of the Konkan division confirmed the acquisition of 7.21 hectares from Sheva-Koliwada as a part of the second phase of land acquisition, started in 1982.

To rehabilitate both the hamlets of the Sheva-Koliwada village, the special land acquisition officer, Uran, purchased 51 hectares of land on 24 May 1985, for Rs 37,42,000 and handed it over to CIDCO on 27 May 1985, with 33.64 hectares demarcated for the people of Sheva hamlet and 17.28 hectares for former residents of Koliwada hamlet.

Plans for resettling the 361 families from Sheva to Bokadvira, 22 Km from the old village, and the 256 families from Koliwada to Boripakhadi, 18 km away from their former homes, were prepared by 8 August 1985.

However, by April 1986, the collector of Raigad reported a lack of funds from JNPT, leading to the resettlement sites being only partially developed.

The 361 families from Sheva received only 237 plots on 10 hectares of land at Bokadvira, while the 256 families from Koliwada were given 105 temporary plots on two hectares at Boripakhadi. This temporary settlement was later named Hanuman Koliwada.

Cramped & Unhygienic Living

Before its residents were relocated, the village had only 88 landless households, but post-displacement, all the families are now landless, meaning they can no longer farm.

The income of the relocated villagers from the fishery sector, already modest, has remained stagnant at around Rs 50,000 to Rs 100,000 annually, leaving them unable to meet basic needs.

Despite all villagers being scheduled tribes (ST), only a small fraction possess caste certificates. This means that the majority of the villagers do not have access to the special provisions, including reservations, given to ST communities in India.

The two hectares on which the transit camp was temporarily built on was earmarked for 256 families. Over the last four decades the count has increased significantly.

A 2024 survey by the School of Habitat Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, showed a significant surge in the number of households, from 256 families to 450, living in the transit camp, a 75% increase.

Houses that were designed to accommodate a family of eight now have up to 18 people.

In the original village the average house size ranged between 3,000-4,000 sq ft while the houses in the transit camp range between 200-300 sq ft.

Houses on the periphery of the settlement have been able to expand by using the space surrounding their allotted transit plot but that is not the case with houses in the middle of the settlement.

The constrained spaces within households necessitate compromises, especially within the kitchen, where women operate in highly confined environments: between 4 and 5 ft, some with no ventilation.

The confined kitchen spaces pose fire hazards, rendering women particularly susceptible, and burns from cooking mishaps are common enough.

Wet & Miserable

Numerous residents have encroached upon the open drains in front of their houses, trying to alleviate the congestion in their homes.

The encroachment of drains has increased waterlogging within the settlement during the monsoons.

Water occasionally seeps through cracks in the walls, causing homes to flood. Residents say the waterlogging has contributed to an increase in malaria and dengue within the settlement compared to the old village.

While a highway now runs near the site of their old village, the access road in the transit camp is only wide enough for two-wheelers and bicycles; emergency vehicles, including fire engines and ambulances, cannot reach the inner houses.

As the houses lack the space for toilets, the people of the settlement rely on six public toilets, two of which are reserved for women. The limited capacity and their distance, approximately 500 m from the settlement, is a significant challenge for the residents.

The unhygienic conditions have led to an increase in ailments, such as diarrhoea.

Potable water is delivered via communal taps provided by the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation every other day.

The settlement is littered with abandoned houses with collapsed roofs as termites have weakened the wooden pillars that supported the roofs. The infestation continues to threaten houses to this day.

Due to the congestion, coupled with the effects of termite infestation, many families have split up and live elsewhere in rented apartments.

Indifference Of The State

The remaining 15.28 hectares of agricultural land near the old village was destroyed after seawater flooded the land due to altered tidal flows along the coast after the port was built.

Over the last four decades, the abandoned farmland has become a mangrove forest.

The government of Maharashtra, in 2022, without consulting the original owners of the land, declared the new mangroves forest land and handed it over to the forest department as a protected reserve forest.

After protests, in November 2022, the JNPT provided 17.28 hectares for rehabilitation of the 256 families near the port’s colony in Uran.

After this decision, there was no progress with rehabilitation plans. The land is barren.

The many reasons for the delay in rehabilitation includes the indifferent attitude of Central and state political leaders, and the district and local administration.

Leadership across political parties and state authorities have shown little interest in the rehabilitation of the people affected by the port project.

Not only have the state government and local authorities ignored the Maharashtra Project Affected Persons Rehabilitation Act 1999, which says that resettlement of “project-affected persons” must take place simultaneously with the project, they have also not ensured basic living conditions in the Hanuman Koliwada transit camp.

According to ministry of rural development rules in 2015, if land acquired under the 2013 land acquisition law isn’t used within five years, it must be given back to the original owner or their heirs.

Yet, the original village site, which remains unused by the JNPT authorities, has not been returned to its former residents.

Fed up with the inaction of the state machinery, the residents have filed at least five court cases—two in the Supreme Court—over the last 11 years against the government.

Residents said that local authorities were hostile to any demands, with the local police attempting in 2022 to measure their houses to check for illegal expansions.

Transit Camp Made Permanent

“There was also an attempt to declare the settlement as a slum and authorise the slum redevelopment authority to take charge of the matter,” said Ramesh Koli, one of the leaders of the fishing community of Hanuman Koliwada.

“This request was also vehemently opposed by the residents stating that they are original villagers displaced due to a project and will not accept the designation of slum.”

The residents of the Hanuman Koliwada transit camp were informed in February 1995 that the site had been declared a revenue village, one recognised as a permanent village in the census. This implies that the transit camp is no longer seen as temporary.

Since then, elections to an independent panchayat, a village-level governing body, have been conducted every five years.

Following demands from the villagers, the JNPT paid property tax to the panchayat, between 2006-2011, for the land in the original village.

It stopped paying tax in 2012, after an order from the Mumbai High Court said Hanuman Koliwada was never a revenue village and its panchayat could not collect tax.

The sarpanch, the chairman of the panchayat, and other villagers filed several right-to-information requests to find out what the legal status of Hanuman Koliwada was.

It was only in April 2024 that they found out that their camp had never been declared a revenue village, following procedures under the Maharashtra Village Panchayats Act, 1959.

Once the tenure of the panchayat ended on 26 January 2024, the district administration wanted to conduct elections, but the villagers boycotted the call for election and decided not to pay tax until they had been resettled and their new village declared a revenue village.

No Hope In Sight

Vithabai Koli, a 55-year-old resident of Hanuman Koliwada, recalled how the original village of Sheva Koliwada had fertile soil and allowed them to be self-sufficient.

She had 11 gunthas (11,979 sq ft) of land, on which she grew fruits and vegetables. After displacement, she said, their cost of living had skyrocketed, and income sources had dwindled.

Although self-help groups are active among the community members, self-employment remains a challenge. The women of the settlement do not have space to set up small-scale enterprises despite several government schemes promoting entrepreneurship.

Another resident, Milind Koli, 58, who suffered an accident and cannot walk unaided, explained how difficult conditions were for the handicapped.

He said his daughters had to carry him to the public toilets.

The cramped living conditions also impede the celebration of festivals and the organisation of community and cultural events.

Yet, the community remains resolute. Their fight, they said, would continue.

(Yash Sharma is pursuing an MA in Regulatory Policy & Governance while Geetanjoy Sahu is Dean of the School of Habitat Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.