New Delhi: An April 2023 Law Commission of India report that recommended retention of India’s colonial-era sedition law relies substantially on a 2018 book, which approves of a law criticised for its misuse, before the Supreme Court suspended its use in May 2022.

There appears to be scant evidence of “extensive consultation” that the Law Commission said it had undertaken before making recommendations about the 153-year-old law on sedition, which most western democracies no longer use.

The authors of the 2018 book, Law of Sedition in India and Freedom of Expression are director Manoj Kumar Sinha and Anurag Deep, professor of law, of New Delhi’s Indian Law Institute, a deemed university with the Chief Justice of India, the solicitor general, and chairperson of the Law Commission among 16 governing council members.

A comparison between the book and the report revealed: paraphrasing, direct reproduction of authors’ conclusions and views; and parallels in the opinions of the author and the Commission.

We also found the Law Commission report omits words that might be sensitive to the sensibilities of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government and safeguards that the book suggests against the law’s misuse. Instead, it recommended harsher penal action.

The 22nd Law Commission of India, headed by former Chief Justice of the Karnataka High Court Ritu Raj Awasthi, in a 24 May 2023 letter to the union minister of law & justice Arjun Ram Meghwal recommended retaining section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) 1860, which criminalises “disaffection”, including “disloyalty and all feelings of enmity” against the State, commonly known as sedition.

Despite widespread criticism of misuse, the Law Commission suggested a widening of the ambit of sedition to a “tendency to incite violence or cause public disorder” and an increased jail term, from the current three years to seven.

Sedition, critics pointed out, is the act of spreading disaffection against the government, not the country. It was meant to stop criticism of the colonial administration, they said, and should have no place in a free society.

Sedition Law Required For ‘Unity’: Law Commission

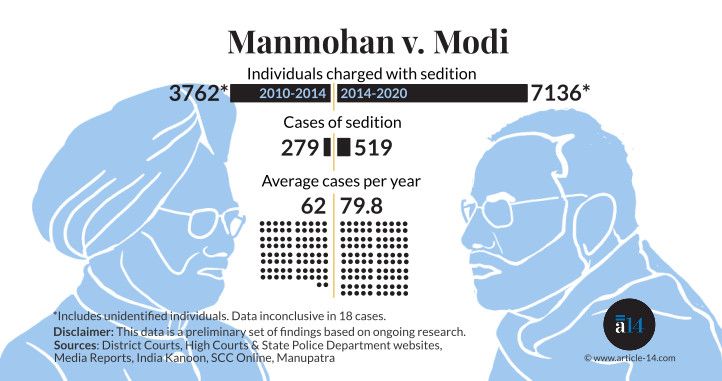

When Article 14’s sedition database was released on 2 February 2021, it revealed a 28% increase in sedition cases every year since Modi came to power in 2014, with most cases filed in violation of Supreme Court guidelines, against critics, dissidents, protesters and others. The database counted sedition cases filed against more than 13,000 people over a decade.

The Law Commission argued that the sedition law was “imperative” to safeguard the “unity and the integrity of the nation”. The report said, “Any allegation of misuse of this provision does not by implication warrant a call for its repeal.”

To address concerns of misuse, the Law Commission report recommended that the government either issue “model guidelines”, or amend the law to make state or central government permission—preceded by an inquiry by an officer of the rank of police inspector—mandatory before filing a first information report (FIR).

On 11 May 2022, in response to nine petitions—five of which used data and stories from Article 14’s sedition database—challenging the constitutionality of sedition, the Supreme Court of India temporarily suspended the law, placing it in abeyance. The central government assured the court that it would “reconsider & re-examine” the law and that it was in favour of “shedding colonial baggage”.

A three-judge special bench headed by the then Chief Justice N V Ramana observed that “the rigours of section 124A of IPC is not in tune with the current social milieu, and was intended for a time when this country was under the colonial regime”.

The Commission seemed to disagree. “Sedition being a colonial legacy is not a valid ground for its repeal”, the report said. “Going by that virtue, the entire framework of the Indian legal system is a colonial legacy.”

Law minister Meghwal said that the “recommendations made in the report are persuasive and not binding” and stated that the government would take an “informed and reasoned” decision after consulting stakeholders.

Report Criticised For Logic, Lack Of Data

The Law Commission report was criticised for the logic it offered in suggesting the retention of the sedition law and its intent.

Apar Gupta, a lawyer and director at Internet Freedom Foundation, a digital rights advocacy group, tweeted on 2 June that the report’s intent did not “appear to be legislative reform but gridlocking/delaying judicial determination”, a reference to the case in the Supreme Court. He said the report lacked “perceptible independence in its commentary”.

For example, wrote Gupta, a chapter was titled "Alleged Misuse of Section 124A". Why, he asked, was it "alleged" and not "established"? There did not appear to be any attempt to obtain data from the home ministry, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) or the courts.

“Depth of inquiry is a press article of a NCRB report,” wrote Gupta.

“This is not the way to go about preparing a report of such importance, especially when the Commission claims to have done this because of the Supreme Court staying the sedition law,” Chitranshul Sinha, a Supreme Court advocate and the author of a 2019 book, The Great Repression — the story of Sedition in India, told Article 14.

“The report appears to rely heavily on one view alone because it appears to have decided the conclusion even before preparation of the report,” said Sinha.

“The Indian Law Institute works directly under the government of India,” Faizan Mustafa, former vice chancellor of the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research, Hyderabad, told Article 14. “So, the book the Commission has heavily relied on is not of an independent expert, though Prof Manoj Sinha is an outstanding scholar of international law.”

The Commission officially acknowledged one of the authors of the 2018 book—Anurag Deep—for holding “in-depth discussions” on the issue with them. No other academicians, lawyers, or individuals have been named.

‘I Was There For 4-5 Hours’

“The law ministry had my book and had forwarded it to the Commission,” Deep, the coauthor, told Article 14. “After that, they got in touch with me and invited me for a discussion.”

Deep said he participated in a panel discussion for 45 minutes and then met each member of the Law Commission separately. “I was there for close to 4-5 hours,” he said.

Asked if the consultation ended with that, he said consultants with the Commission were in “constant touch” with him “over the phone and email”.

“I am not aware if anybody else was consulted,” said Deep.

The Commission’s report claimed it held “extensive deliberations with all the relevant stakeholders, scholars, academicians, intellectuals, etc.” and released a “Consultation Paper on Sedition” on its website in 2018, inviting comments from the “concerned intelligentsia and the public in general”.

The details of such an exercise are not available on the Commission’s website.

Article 14 sought comment from Law Commission chairperson Justice Awasthi. Refusing to answer questions, he said over the phone that “the public can form their own opinion”.

Asked about others, apart from Deep, who were consulted, the former high court judge said, “Why should I divulge the details? Who are you to ask these questions? I will not do it.”

Another member of the Law Commission, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he could not provide details of others whose inputs carried the same weight as Deep’s. “Talk to our chairperson,” he said. “He will tell you,” they said.

Lubhyathi Rangarajan, who heads Article 14’s sedition database and is an independent lawyer and researcher, said that the Commission did not appear to seek the views of those in favour of repealing sedition.

“I do remember being part of the consultation process on the death penalty, when [former Delhi High Court Chief] Justice A P Shah was heading the Commission, in 2014-15,” said Rangarajan.

“There were multiple stakeholders from across disciplines who were invited to speak at a day-long event,” said Rangarajan. “A questionnaire was circulated prior to that, views were sought from people in favour of and against the death penalty, and anyone in the middle.”

“A Law Commission is accountable to the people, not just to the government in power,” said Rangarajan. “It is meant to be a public process, inviting diverse views.”

Paraphrasing The Book

The Law Commission cited various threats to India’s internal security—including militancy and ethnic conflict in the north-east, Maoist extremism, terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir, and secessionist activities in other parts of the country, such as Punjab—to defend its recommendation of retaining the law on sedition.

“For over more than five decades of their existence, the Maoists/Naxalites, in the garb of advocating liberty and self-determination, demolish hospitals, burn schools, damage roads and kill people participating in electoral process,” said the Commission report. “The real and imminent threat from these groups has resulted in mass scale violence, rape, targeted killings, etc.”

This paragraph is a paraphrase from page 194 of the 2018 book. The Commission report did not footnote the source of the content.

The Commission omits phrases from the book that could be sensitive to Modi’s government, such as references to Maoists who “persecute religious minorities” and plan “ethnic cleansing”.

Modi’s government and his party have been frequently accused (here, here, here and here) of persecuting India’s minority communities, especially Muslims.

Similarly, while using a United States Supreme Court case from 1925 to support its stand in point 8.13 of the report, the Commission reproduces, word-by-word, the entire description of the case from page 209 of the book.

Justifying why section 124A should be retained, the Commission report, in point 9.2 of the “Conclusion” section, reproduces a paragraph from the book, omitting a line that talks of the state’s duty to safeguard the freedom of citizens, stability, and peace.

Borrowed Views, Omissions

The Law Commission report cherry-picks several views from the book to justify its recommendations. It credits the book 11 times, making it evident that the authors’ views had a major impact on the report.

But there are instances when the Commission borrows ideas and views of the authors and showcases them as its own.

Like the authors of the book, the Commission faults the police for the misuse of the sedition law. “The root of the problem lies in the complicity of the police,” said the report. “Sometimes, in an overzeal (sic) to please the political masters, the police action in this regard becomes partisan and not as per the law.”

The book's authors blame the subordinate judiciary for their erroneous application of the law. This is omitted by the Commission. Both the Law Commission and the book say nothing of the law being misused by the political establishment.

As Article 14’s database reported, 96% of sedition cases filed against 405 Indians for criticising politicians & governments between 2010 & 2021 were registered after 2014: 149 were accused of making “critical” and/or “derogatory” remarks against Prime Narendra Modi, and 144 against Uttar Pradesh (UP) chief minister Yogi Adityanath.

“No police force acts without the support of the political establishment,” said Sinha, the Supreme Court lawyer.

“The district judiciary fails us too by mechanically deciding remand cases in such matters,” said Sinha. “There is a lack of application of judicial mind, with civil rights not being a consideration. The sedition law is a political weapon, and that is where the buck stops.”

The book’s influence on the Commission’s views is also apparent in its opinion that in the absence of a sedition law, more draconian special counter-terrorism laws would be used.

The Commission seemed to have borrowed this logic from the authors’ conclusion that the British, out of “human rights considerations”, brought in the sedition law to “reduce the sufferings of citizens engaged in free speech”.

The authors reproduce a quote attributed to legal member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council in India and author of the Indian Evidence Act 1872, Sir James Stephen, who had said, “Section 124-A should be passed into law, because if there were no provision in the law of India, the offence would fall under the common law of England, and would be more severely punishable.”

The common law of England Stephen referred to was the law of treason, which was, until 1998, punishable by death. The law of treason still exists in the UK, although it is rarely invoked, and the law of sedition was repealed in 2009.

“In the absence of a provision like Section 124A of IPC, any expression that incites violence against the government, would invariably be tried under the special laws and counter terror legislation, which contain much more stringent provisions to deal with the accused,” the Commission said.

Mustafa said this argument would make sense if a person committed violence and was prosecuted under special counter-terrorism laws. “If someone has done any overt act of violence, they should certainly be severely punished,” he said. “Such overt acts will come under those special laws, not mere speech. Right now, they want to criminalise mere speech.”

The Law Commission report recommends the reintroduction of what is called the ‘tendency test’, which some experts said was “outdated and outlawed” in Indian jurisprudence.

Rangarajan explained the tendency test with the help of an example.

“A social media post saying the words, ‘I Stand for Pakistan’, in the aftermath of the Pulwama Terror attacks, is an example based on real life,” said Rangarajan. “Any judge, should they feel the need to be suddenly nationalist, would read these words as 'tending' to incite violence even though no proximate or imminent threat to any person existed.”

The Commission advises incorporating the tendency test in section 124A by adding the words “with a tendency to incite violence or cause public disorder”.

It defines “tendency” as a “mere inclination to incite violence or cause public disorder rather than proof of actual violence or imminent threat to violence”.

The authors of the 2018 book have supported the tendency test by mainly relying on four Supreme Court judgements—State of Bihar vs Shailabala Devi of 1952, Ramji Lal Modi vs State of U.P of 1957, Babulal Parate vs State of Maharashtra of 1961, and the Kedarnath Singh vs State of Bihar of 1962.

Each of these judgments from the days after India’s independence did indeed approve the tendency test for Indian jurisprudence, but experts said it was outdated.

India is not going through internal strife as it did immediately after independence or even at the time of the Khalistan movement, said Sinha. “It is a mature democracy and is not as brittle as the law suggests it is,” he said.

The authors in their concluding remarks on page 262 of the book state that the “requirement of tendency of violence or disorder needs to be expressly incorporated in the main body of Section 124A”. The Commission recommended the same.

Mustafa pointed out that the Supreme Court had said that “mere speech” should not be punished. “Now you are enhancing the punishment from three to seven years,” he said. “Can you go back to a dated idea [tendency test] like this?”

“After freedom of speech is incorporated in the constitution, sedition on the grounds of just some speech without anything more looks inconsistent with the expanding scope of freedom of speech,” said Mustafa. “Democracy cannot remain democracy without free speech.”

While the Commission’s report paraphrases portions of the book and borrows its ideas, it avoids mitigation measures suggested by the authors.

For example, the Law Commission omits stronger safeguards to the use of sedition law that the book suggests: assigning punishment to a person accused of sedition based on the severity of their action; incorporating obligations on the state to prove an accused’s “intention to commit disaffection, hatred, or contempt towards government and create public disorder”—not just prove ‘inclination’ as is now recommended; and requiring the state to ask “good conduct” security bonds from persons found to be disseminating “seditious material”.

The union government will now hold further consultations based on the Law Commission report, while it undertakes a review of the IPC and the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973.

“I honestly do not think this report will go anywhere,” Sinha said. “I do fear that the legislature will actually replace section 124A with a more draconian law.”

(Saurav Das is an independent investigative journalist and transparency activist.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.