New Delhi: “Judicial review of legislative and executive actions is an integral part of the constitutional scheme. I would go as far as to state that it is the heart and soul of the Indian Constitution. In my humble view, in the absence of judicial review, people's faith in our Constitution would have diminished.”

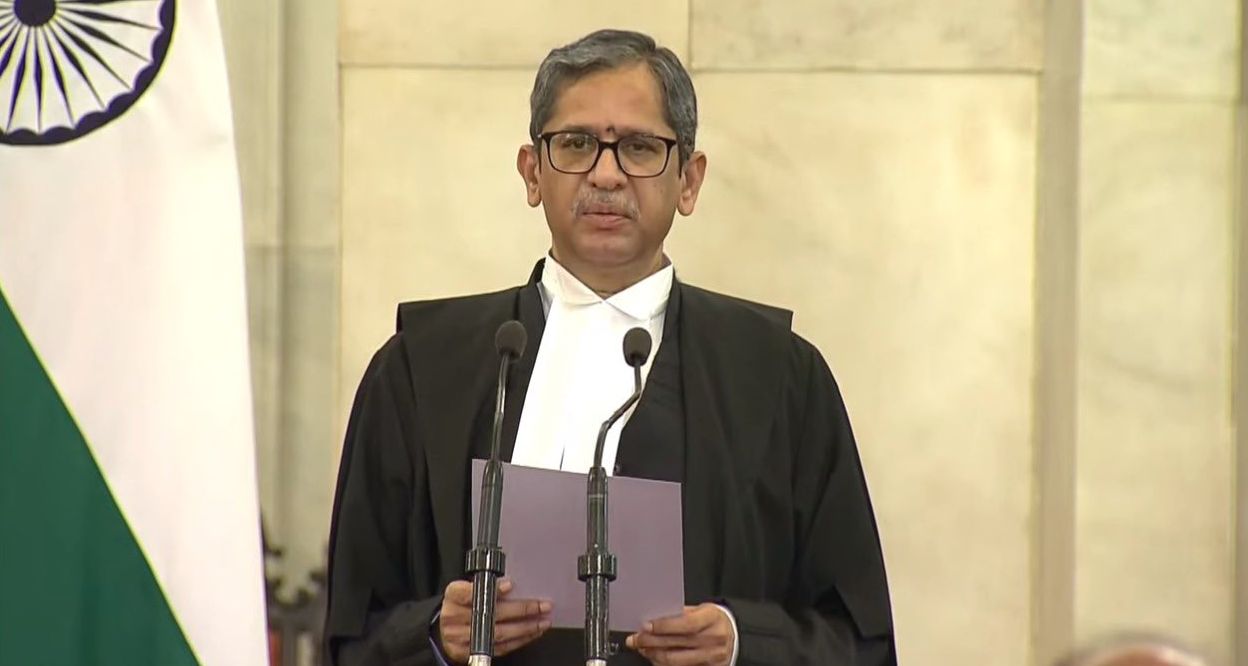

This is what Chief Justice of India N V Ramana said on 23 July 2022, during one of at least 29 lectures he delivered over the course of his 16-month tenure as India’s top judge.

Yet, during Ramana’s time as Chief Justice, the Supreme Court did not exercise this power of judicial review in 53 cases requiring a constitution bench, which comprises five or more judges and deliberates on cases of constitutional significance; and in several other cases that do not require a constitution bench but are with widespread ramifications and of national importance.

Challenges to these 53 cases saw no progress in Ramana’s Court, much like in his predecessors’ courts. Similarly, little or no progress was apparent in other cases that we analysed. Of these pending cases, we identified six:

—the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir (pending for 1,115 days)

—a challenge to electoral bonds for being opaque and encouraging murky political funding (1,816 days)

—a Karnataka government ban on the hijab for Muslim students in government educational institutions (159 days)

—a Union government reservation policy based only on economic criteria and not caste factors (1,323 days)

—a challenge to the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, widely criticised as a tool to quell dissent (1105 days)

—a challenge to the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, which provides fast track citizenship to only non-Muslims from three neighbouring countries (987 days)

As “master of the roster”, the Chief Justice is empowered to constitute such benches, including constitution benches, decide cases they will hear, and assign cases to specific benches. When cases are not listed for hearing, said experts, the responsibility lies with the Chief Justice.

Only one constitution bench of five judges was constituted by Chief Justice Ramana. In September 2021, that bench heard a curative petition (final stage for review of a judgement) relating to a dispute over contractual obligations between the Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Ltd, a state electricity regulator, and Adani Power (Mundra) Limited, a power generation company. The case ended five months later in February 2022 in an out-of-court settlement.

On 22 August 2022, four days before his retirement, Ramana said that he had constituted a five-judge constitution bench to hear a legal dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 2018 between the Delhi government and the union government over control over administrative services in the national capital. Hearings have not yet started.

There were other issues relating to the higher judiciary that Chief Justice Ramana failed to pursue, such as long-standing demands for reforms, transparency in the collegium system of picking high court and Supreme Court and judges; a more transparent system of listing cases, live-streaming of court proceedings; and fixing criteria for selection of judges.

Article 14 spoke to petitioners who have challenged government actions and have awaited hearings for months and years and to lawyers closely associated with the Supreme Court judicial system. Two common emotions emerged in the conversations—disappointment and little hope.

Abrogation Of Article 370 In J&K: Pending For 1,115 Days

Petitioners argue that downgrading a state to a union territory is unconstitutional and Article 370 could not have been amended without the concurrence of J&K’s constituent assembly, which had been dissolved. The governor, appointed by the union government, gave that concurrence.

Formal name: Manohar Lal Sharma vs Union of India

Last hearing by: Chief Justice Ramana, Justice S K Kaul, Justice R Subhash Reddy, Justice B R Gavai and Justice Surya Kant

First date of hearing: 16 August 2019

Last date of hearing: 2 March 2020 (30 months ago)

Hearings: 11

Last request for listing: 25 April 2022 before Chief Justice Ramana.

Reaction: “Let me see.”

“One of the major challenges to the protection of rule of law and human rights is the inability of the formal justice system to deliver speedy and affordable justice to all.” —Chief Justice Ramana, Srinagar, 14 May 2022.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/08-August/24-Wed/Adnan%20Mir.jpg]]

Around 23 petitions have been filed challenging the constitutionality of the 5 and 6 August 2019 presidential orders (here and here) that ended J&K’s special constitutional status and the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, which divided the state into two union territories: J&K and Ladakh.

The case has not been heard in more than two-and-a-half years. It was Chief Justice Ramana who, in 2019 and early 2020, headed the constitution bench as a judge. The last time this constitution bench sat on 2 March 2020, it refused the request made by some petitioners to refer the case to a larger bench of seven judges.

When the petitioners asked for “an early date” for the hearings to resume, the bench said that would be decided “depending on the schedule of the Sabarimala Reference hearing”, a reference to the Sabarimala case in which a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court referred questions on the ambit and scope of religious freedom to a larger bench of seven judges. This hearing never happened.

There was a request to list the case in April 2022 before Chief Justice Ramana’s bench. His answer: “We’ll see”.

Ramana said he would have to reconstitute the five-judge constitution bench and that it would be listed “after the vacation”. The vacation ended on 10 July, but the case never made it to the list.

“There is a trend of SC and HC judges giving speeches that give confidence in our judicial system,”Adnan Ashraf Mir, one of the petitioners in the case and spokesperson for the J&K People’s Conference party, told Article 14. “But when it comes to hearing matters in court, the utterances don’t match the performance of their orders.”

“I personally feel some disappointment in the SC not hearing the case,” said Mir. “The judges must show some willingness to hear this case or they must give an explanation as to why they can’t hear the case on priority despite (sic) three years.”

Mir said there was a growing feeling amongst Kashmiris that the odds were against them and that no institution was willing to defend their rights. “This is dangerous,” he said. “What happened to J&K sets a precedent for other states too. It can be replicated elsewhere.”

During the early days of the constitution-bench hearings, the petitioners had sought a “status quo” as an interim measure, fearing that if realities on the ground changed while the case was pending, the case could be irrelevant. The Bench rejected this argument, with Justice Gavai saying the court could always reverse the effects of the Act.

“After the effects of the Act are executed on the ground, they are difficult to reverse,” said Mir. “What is happening with the domicile bill, matters of employment, etc, cannot be reversed. I would have liked the Court to show some urgency. There seems to be a bias, from an outsider point-of-view.”

Challenge To Electoral Bonds: Pending For 1,816 Days

Petitioners allege electoral bonds allow opaque political funding, is detrimental to electoral democracy, and is illegal because it was passed as a money bill, which meant it escaped scrutiny of Parliament’s upper house, the Rajya Sabha.

Formal name: Association for Democratic Reforms vs Union of India

Last hearing by: former Chief Justice S A Bobde, Justice A S Bopanna, and Justice V Ramasubramaniam

First date of hearing: 5 April 2019

Last date of hearing: 29 March 2020 (30 months ago)

Hearings: 8

Last request for listing: 25 April 2022 before Chief Justice Ramana.

Reaction: “Will take it up.”

“Citizens can strengthen the “Rule of Law” by being knowledgeable about it and by applying it to their daily conduct and pushing for justice when needed.” —Chief Justice Ramana, P D Desai memorial lecture, 30 June 2021.

The petitioners challenged the electoral-bonds scheme, which the union government launched on 02 January 2018, arguing it was anonymous, allowed unaccounted corporate funding to political parties, and was wrongly passed as a finance bill.

Investigative media reporting in November 2019 revealed how the Election Commission of India (ECI), the Reserve Bank of India, and the ministries of finance and law & justice opposed the electoral bonds for “scope of its misuse”, for “setting a bad precedent”, and “encouraging money laundering”. The ECI described the scheme as a “retrograde step as far as transparency of donations is concerned” and called for its withdrawal.

The petitioners sought a stay on the scheme as an interim measure, which the Supreme Court refused to grant twice—once by a bench headed by then Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi in April 2019, and the second time by a bench headed by then Chief Justice Bobde in March 2021.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/08-August/24-Wed/Jagdeep%20Chhokar.jpg]]

“The impact of this has been that the scheme continues, and unaccounted money whose source is not known, except to the government, continues to benefit political parties with a disproportionately large chunk of money going to the ruling party,” Jagdeep Chhokar, founding member of the Association for Democratic Reforms, one of the three petitioners in the case, told Article 14.

On 5 April 2022, senior advocate Prashant Bhushan requested Chief Justice Ramana’s bench to list the case for hearing. He cited an example from West Bengal, where a Calcutta-based company paid Rs 40 crore through electoral bonds, allegedly hoping to stop excise raids.

“This is distorting democracy,” Bhushan told Ramana.

Ramana blamed the delay in hearing the case on the pandemic and promised that they would “take it up”. There was no hearing in more than four months after Ramana made this promise.

“We attempted to get the matter listed at least five to six times, but to no avail,” said Chhokar. “In April 2019, the SC said that the petition raises ‘weighty issues which have a tremendous bearing on the electoral process in the country’. So I ask, do these weighty issues not warrant an urgent hearing? I am sad and disappointed. We’ll keep trying.”

Challenge To Constitutionality Of UAPA: Pending For 1,105 Days

Petitioners argue that provisions of the UAPA, India’s anti-terrorism law, are vague, violate freedom of speech, and provide broad powers to the State without a “judicial application of mind”.

Formal name: Sajal Awasthi vs Union of India

Last hearing by: Former Chief Justice Gogoi and Justice Ashok Bhushan.

First date of hearing: 9 September 2019

Last date of hearing: Never since first hearing (35 months ago)

Hearings: 1

Last request for listing: Not known

Reaction: NA

“It is necessary for us all, the citizens of the world, to work tirelessly to sustain and further the liberty, freedom, and democracy our forefathers have fought for.” — Chief Justice Ramana, Philadelphia, USA, 26 June 2022.

Several petitioners have approached the Supreme Court since 2019 challenging the constitutionality of various provisions of the UAPA, which as Article 14 has reported (here, here and here), puts the burden of proof on the accused and violates constitutional provisions.

The main case, filed by one Sajal Awasthi and the Association for Protection of Civil Rights in 2019, asked the Supreme Court to decide if 2019 amendments to the UAPA, which broadened the definition of ‘terrorist act’ and empowered the State to label anyone a ‘terrorist’ without trial or proof, violated Article 19(1)(a)—freedom of speech—of the Consitution.

Then Chief Justice Gogoi issued a notice, asking the union government to respond, but there was no hearing. During Ramana’s tenure as Chief Justice, several journalists and civil society members challenged before the Supreme Court what they called “manifestly arbitrary” UAPA powers of the State to “crush dissent”.

In November 2021, one such challenge came to Chief Justice Ramana’s bench, which issued a notice but never since heard the case.

Instead of deciding the constitutionality of the UAPA, the Supreme Court effectively stayed a Delhi High Court order, in a bail hearing, restricting the State’s ability to charge someone under the UAPA.

In a 15 June 2021 bail order, the Delhi High Court called the definition of terrorist act under the UAPA as “vague” and held that “usual offences no matter how grave, egregious or heinous are not covered under UAPA”. Three days later on 18 June 2021, the Supreme Court said that the Delhi High Court order should “not be treated as a precedent”.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/08-August/24-Wed/Shyam%20Meera%20Singh.jpg]]

Shyam Meera Singh, a journalist and a petitioner who faces UAPA charges, said he was “surprised” the Supreme Court was not hearing challenges to the UAPA.

“Not entirely unexpected though,” Singh told Article 14. “There has been no development in the cases, and the FIR (first information report) under the UAPA against me still stands.”

“I can’t go abroad, and nor can I apply for a government job—not that I want to,” said Singh. “There are small mercies every now and then, but overall, I do not have much hope in the judiciary. The entire judiciary is compromised, more so the lower judiciary.”

Reservation Based on Economic Criteria: Pending For 1,323 Days

Petitioners argue that reservation for government jobs and education based on economic criteria alone, without considering Dalit, tribal or backward-caste status, and other social factors, is unconstitutional.

Formal name: Youth for Equality vs Union of India

Last hearing by: former Chief Justice Bobde, Justice Subhash Reddy, and Justice Gavai.

First date of hearing: 12 March 2019.

Last date of hearing: 5 August 2020 (24 months ago).

Hearings: 6

Last request for listing: Not known.

Reaction: NA

“I am a strong proponent of affirmative action. To enrich the pool of talent, I strongly propose reservation for girls in legal education.” —Chief Justice Ramana, New Delhi, 10 March 2022.

On 9 January 2019, Parliament passed the 103rd Constitution Amendment Act, which amended Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution and empowered the State to reserve 10% of higher-education admissions and government jobs on economic criteria or based on family income.

Over 20 petitions were filed challenging the Act for violating the 50% ceiling limit on reservations imposed by the Supreme Court in November 1992 for excluding scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward castes.

After five days of arguments, on 5 August 2020, a three-judge bench headed by then Chief Justice Bobde decided to refer the matter to a larger bench of five judges. There has been no hearing since.

Under Chief Justice Ramana’s tenure, no attempts have been made to constitute a constitution bench of five judges.

“You are allowing the status quo to ultimately become the result,” Sanjoy Ghose, a Delhi High Court senior advocate, unconnected with this petition, told Article 14. “So, ultimately, with the passage of time, this is a fait accompli, and the entire exercise becomes only academic”.

The Citizenship Amendment Act: Pending for 987 Days

Petitioners argue that the Citizenship Amendment Act, passed in 2019, is discriminatory, based as they argue it is on religion, violating the right to live with dignity guaranteed under Article 21 and is, therefore, unconstitutional.

Formal name: Indian Union Muslim League vs Union of India

Last hearing by: former Chief Justice Bobde, Justice Gavai and Justice Surya Kant

First date of hearing: 18 December 2019

Last date of hearing: 22 January 2020 (31 months ago)

Hearings: 2

Last request for listing: Not known

Reaction: NA

“Educated youth cannot remain aloof from social reality. You have a special responsibility… You must emerge as leaders. After all, political consciousness and well-informed debates can steer the nation into a glorious future as envisioned by our Constitution. A responsive youth is vital for strengthening democracy.” —Chief Justice Ramana, National Law University, Delhi, 9 December 2021.

The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi enacted the CAA in December 2019. The law provides fast-track citizenship for non-Muslim migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Soon after, large-scale protests erupted across India. Since the government has not yet framed rules, the law has not been implemented.

Over 200 petitions have been filed before the Supreme Court challenging the constitutional validity of the CAA. They primarily contend that the CAA is exclusionary, as it excludes Muslims, and violates Article 14 of the Constitution, which guarantees equality to all persons, including non-citizens.

A Supreme Court bench headed by then Chief Justice Bobde held two hearings on 18 December 2019 and 22 January 2020 and refused to stay the law. The last hearing was on 22 January 2020. There’s been no hearing since.

On 20 May 2020, another petition seeking a stay on the law limited to Assam was heard by Chief Justice Bobde’s Bench. The Bench refused to stay the law and only issued a notice to the union government.

“The entire country in such huge numbers expressed collective displeasure and anger at the law; does it not warrant a hearing before the apex court?” Banojyotsna Lahiri, a founding member of United Against Hate group, one of the groups that has challenged the CAA law, told Article 14. “How else should citizens speak up in clearer terms?”

“Chief Justice Ramana should have shown his progressive side, not only in his speeches but also in his own turf by way of judgements,” said Lahiri.

Other Cases of Public Interest Ignored

There are other cases that Chief Justice Ramana has left untouched, sometimes despite multiple requests by lawyers.

Most recently, Chief Justice Ramana did not list the Pegasus case, in which journalists and civil society members seek a judicial probe to investigate if the union government used Israeli spyware called Pegasus to spy on journalists and other citizens and if due process was followed.

The 11 petitions, pending since 22 July 2021, were expected to be listed on 12 August 2022. The case is now listed on 2 September, after Ramana’s retirement. A technical committee headed by former Supreme Court Justice R V Raveendran has reportedly submitted its final report.

On 2 August, an advocate requested Ramana’s bench for a hearing against a 15 March 2022 Karnataka High Court judgement upholding a state-government ban on hijabs in state educational institutions. Ramana said one of the judges was unwell. No date was given. It has now been 159 days since the petition was first filed.

In April and July, at least two requests (here and here) for urgent listing of the hijab case were made before the Chief Justice’s bench. Chief Justice Ramana promised he would. On 26 April, he said, “Wait for two days.” On 13 July, he said, “Wait till next week.” The case has not yet been listed.

“In normal practice, special leave petitions (or SLP, an appeal against any judgement or order of any Court/tribunal) are listed for first hearing within 5-6 days from the date SLP is numbered,” said Fauzia Shakil, a lawyer for the hijab case. “In our case, it has been months. It just shows that the Supreme Court is reluctant to hear the matter.”

(Saurav Das is an investigative journalist.)