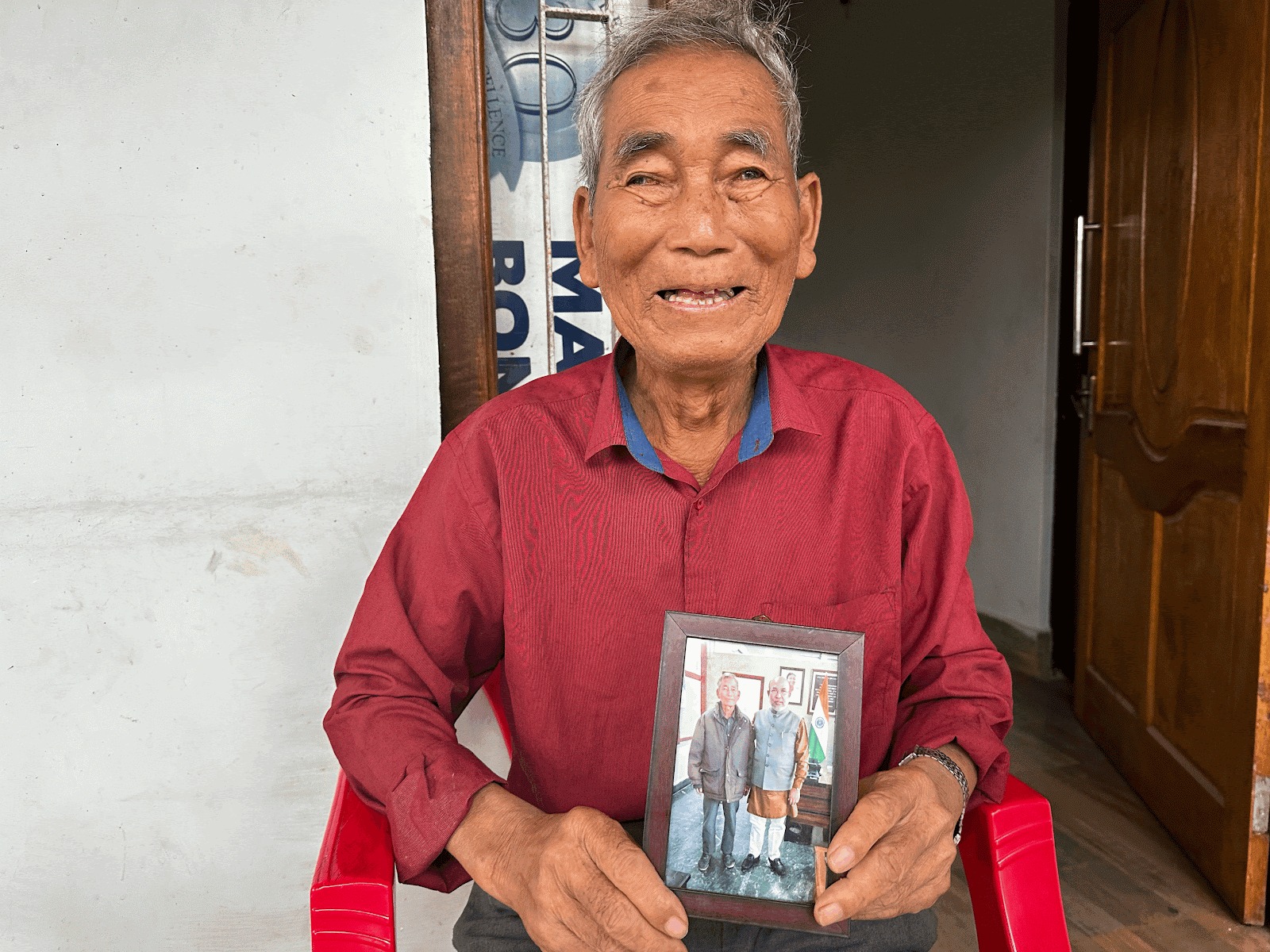

Kangpokpi, Imphal, Ukhrul, Tengnoupal, and Mao (Manipur): Lunhokam Ngailut recalled the days when timber flowed from the forested hills of Manipur to the Imphal Valley, brokered by well-connected men.

One of those, according to Ngailut, in his nineties, a lean, smiling man with thinning hair, was Gaurav Singh, the father of Manipur’s former chief minister N Biren Singh. Gaurav Singh was a major timber trader, sourcing wood from tribal lands, bypassing the permit requirements imposed on local Kuki and Naga communities, according to 10 tribal chiefs and timber traders who spoke to Article 14 for this story.

“We must have cleared five or six acres of forest then,” said Ngailut, a former chief of a Thadou Kuki village called Changoubung in Kangpokpi district, recalling the 1950s. “No permits were needed because he was well-connected with the state departments and the police,”

Ngailut said the land was classified as a reserve forest, where forest-dwelling communities such as the Kuki Zo and Naga tribes are legally required to obtain permits to extract resources.

As a new government takes charge in ethnically divided, conflict-ravaged Manipur, this history matters because the state’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has blamed the Kuki Zo tribes both for the violence since 2023 and for deforestation in the hills.

The official narrative put forth by Biren Singh—repeated in courtrooms and the media—casts the conflict as a war against illegal settlers growing poppy, with poppy fields blamed for disappearing forests.

“All our forest have been destroyed while we are trying to pull each other down,” Biren Singh wrote on X (formerly Twitter) on 3 December 2025. “It is suspected that armed militants are involved in these illicit activities. Unless we take concrete action, the state will face an existential crisis.” The militants Biren Singh referred to were minority Kuki-Zo tribals.

But an Article 14 investigation using satellite imagery, government maps and records and official data obtained by using the right-to-information (RTI) act, shows that poppy cultivation has largely spread into areas already cleared by logging, much of it commercial and often state-sanctioned.

These findings challenge the claim that tribal poppy farmers caused Manipur’s environmental crisis and point instead to the role of powerful interests, including political elites, in shaping both the state’s forests and its conflict.

When Article 14 sought comment from Biren Singh over the narrative he propagated, he responded only with a smiley over WhatsApp.

‘A Majoritarian Project’

Manipur has been in civil conflict for over two years since ethnic clashes broke out on 3 May 2023 between the valley-based Meitei Hindu majority and the Kuki-Zo tribals, mainly Christian, living alongside Naga communities in the hill districts that make up about 14% of the state’s population of over 2 million but occupy 90% of the area.

The violence followed a 2023 Manipur High Court order recommending scheduled tribe status for Meiteis, triggering protests that escalated into targeted attacks and clashes.

Around 300 people have been killed, and more than 60,000 displaced on both sides. Tribal minorities bore the brunt of the violence, particularly in the early weeks, facing mass killings, sexual violence and forced displacement from the valley.

Rights groups, such as Amnesty International, and scholars say the BJP’s repeated targeting of minorities fits a wider pattern of scapegoating marginalised communities (here, here and here). They argue that blaming tribal poppy cultivation mirrors earlier efforts to pin social or environmental crises on minorities, often without evidence.

Kham Khan Suan Hausing, a political science professor at the University of Hyderabad and a Kuki Zo, said claims of widespread poppy cultivation are exaggerated and selectively deployed.

“The environmental cost is amplified in the mainstream Indian imagination to make pliable constituencies in the valley and outside the state believe that the Kukis pose a grave environmental threat,” said Hausing.

“That’s how majoritarian projects work.”

Public Institutions, Political Ends

More troubling, said experts, is the alleged use of publicly funded institutions to advance political narratives.

By repeatedly taking suo motu cognisance, India’s National Green Tribunal (NGT)—the country’s top environmental court—appears to be lending weight to politically driven claims of environmental loss in Manipur’s tribal areas, while granting environmental clearances to extractive mining projects in Central India’s tribal regions.

On 9 May 2024, the NGT took suo motu cognisance of a post on X by Biren Singh. Calling it “mind-boggling data”, Biren Singh claimed that 877 sq km of forest was destroyed “primarily for the cultivation of poppy”, and 291 encroachers were evicted since the BJP government came to power.

In August 2024, the National Green Tribunal took suo motu notice of a local news report alleging that “Khuga reserve forest land” was being put up for sale in Churachandpur, a Kuki-Zo–dominated district. The land, however, was neither reserve nor protected forest but unclassed forest, where land use is governed by the revenue department or local communities under customary law. Finding no basis to proceed, the tribunal closed the matter—disposing of the case in February 2025.

Again in July 2025, the tribunal took suo motu cognisance of a news item, "Satellite Data Shows Manipur Lost 52,000 Acres of Forest In 4 Years: Study" on NDTV, based on a satellite analysis report by Suhora, a private satellite analytics company working based in Noida, Uttar Pradesh.

The ministry of environment, forests and climate change, in its response, said that they were neither aware of the study conducted by Suhora nor of the methodology used for assessing the forest cover. This case remains pending in the tribunal.

Article 14 accessed the Suhora report, which attributed Manipur’s forest loss to shifting cultivation, illegal logging, ‘proliferation of poppy cultivation, especially in remote hill regions, which has led to widespread clearing of forests and infrastructure development.

When we asked for the satellite images (or coordinates) that point to the drivers of deforestation in Manipur, Suhora replied, “Our analysis did not attempt to attribute deforestation to individual drivers or quantify their proportional impact. Our study focused on detecting land-cover change patterns, specifically, areas of deforestation and afforestation, using high-resolution satellite datasets.”

That year, Manipur’s Remote Sensing Applications Centre (MARSAC) released a government study mapping poppy cultivation in the state. Article 14 accessed the report, which tracked poppy fields over three periods—2021–22, 2022–23 and 2023–24—using satellite images and government records.

The MARSAC study combined satellite images from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) with data from the state’s narcotics, border and forest departments. It found that by 2021–22, nearly 29,000 acres of hill land across eight districts were under poppy cultivation. For comparison, Myanmar’s total area under opium cultivation in 2025 was about 133,000 acres.

A forest department source, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Article 14 that much of this data collection had been done at record speed and on priority after the vilification of the Kuki Zo community had already begun.

By then, four Kuki Zo churches in Imphal had been destroyed, evictions of Kuki Zo villages had begun—ostensibly to occupy protected forests—and a state cabinet-led exercise was launched to identify “illegal immigrants” in four districts.

“All those in the forest department, whether Kuki, Meitei or Naga, knew exactly what the objective of this report was going to be,” said the forest department source, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“But we had no choice but to do our job since the orders were coming directly from the top,.”

Manipur’s Fading Forests

The north-eastern part of India, comprising eight states, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura, is widely acknowledged as one of India’s four prominent biodiversity hotspots.

Though it covers 7.98% of the nation’s land area, the region accounts for 21.08% of India’s forest and tree cover, according to the 2023 India State of Forest Report (ISFR), a biennial publication of the Forest Survey of India.

According to the IFSR 2023, the region—including Manipur—registered a net loss of 327 sq km in forest and tree cover, with only Mizoram and Sikkim reporting gains since 2021.

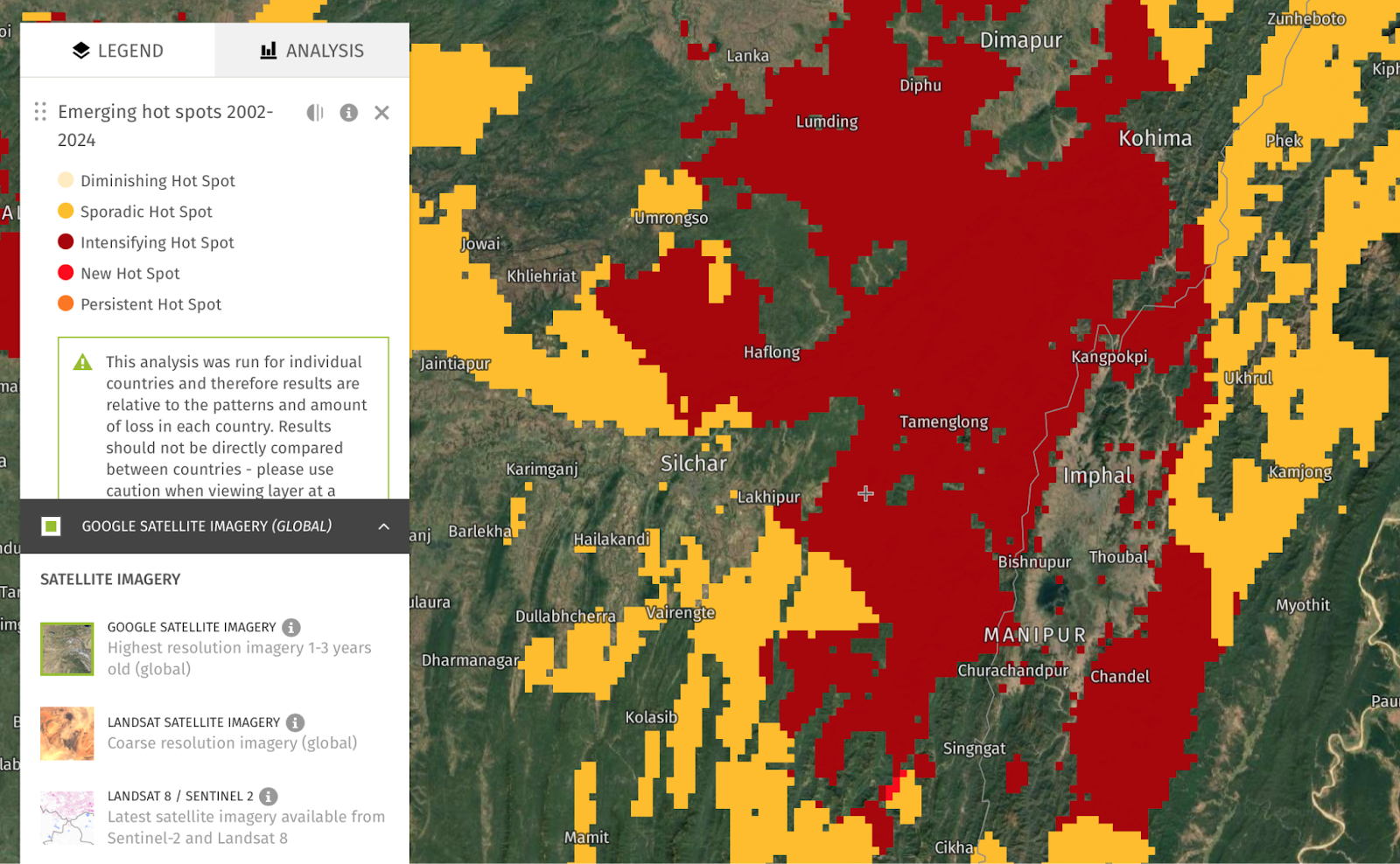

According to Global Forest Watch (GFW), an online platform that tracks deforestation, Manipur lost 255,000 hectares of forest cover from 2002 to 2024, and released 150 metric tonnes of carbon emissions into the atmosphere, most of it from the hill districts of Churachandpur, Tamenglong, Ukhrul, Chandel and Senapati.

Although Manipur’s carbon emissions may appear minor compared to those from major industrial sectors or fossil‑fuel use elsewhere, deforestation-driven emissions have serious consequences.

Forest loss accelerates soil erosion, reduces biodiversity, and heightens vulnerability to landslides and floods. Standing trees represent avoided emissions by actively sequestering carbon dioxide that would otherwise enter the atmosphere.

While the GFW identifies logging as a key source of “temporary disturbances,” it also points to jhum or shifting cultivation—the traditional slash‑and‑burn practice in the hills—as the dominant driver of forest loss in Manipur.

Yet, the roles of shifting cultivation and poppy cultivation in the hills, though significant, are often overstated, diverting attention from other critical but under‑examined drivers of environmental degradation.

‘Mischaracterisation’

A retired forest department officer in Kangpokpi, who served across Manipur’s hill districts for over three decades, said it was a mischaracterisation to claim that hill tribes—Naga or Kuki—clear virgin forests for poppy cultivation.

“Until 1988, the government of India’s forest policy was about revenue generation,” the officer said, requesting anonymity for fear of retaliation. “Across India, including Manipur, forest departments were given bulldozers to build roads and extract as much timber as possible.”

He told Article 14 that the policy shifted to conservation only in 1988, by which time “all the good timber had already been removed”. The land then came under jhum cultivation, which, he said, is carried out on secondary growth, not virgin forest. “These already degraded areas are later used for poppy cultivation, which involves fertilisers.”

Mani Charenamei, a former member of Parliament (MP) and forest officer from the Liangmai Naga tribe, recalled that the community’s first encounter with the post-Independence Indian state was through timber extraction.

“When my people protested against merchants cutting our forests, they were arrested,” he said. His father was among those taken to Imphal for opposing the felling.

What The Data Reveal

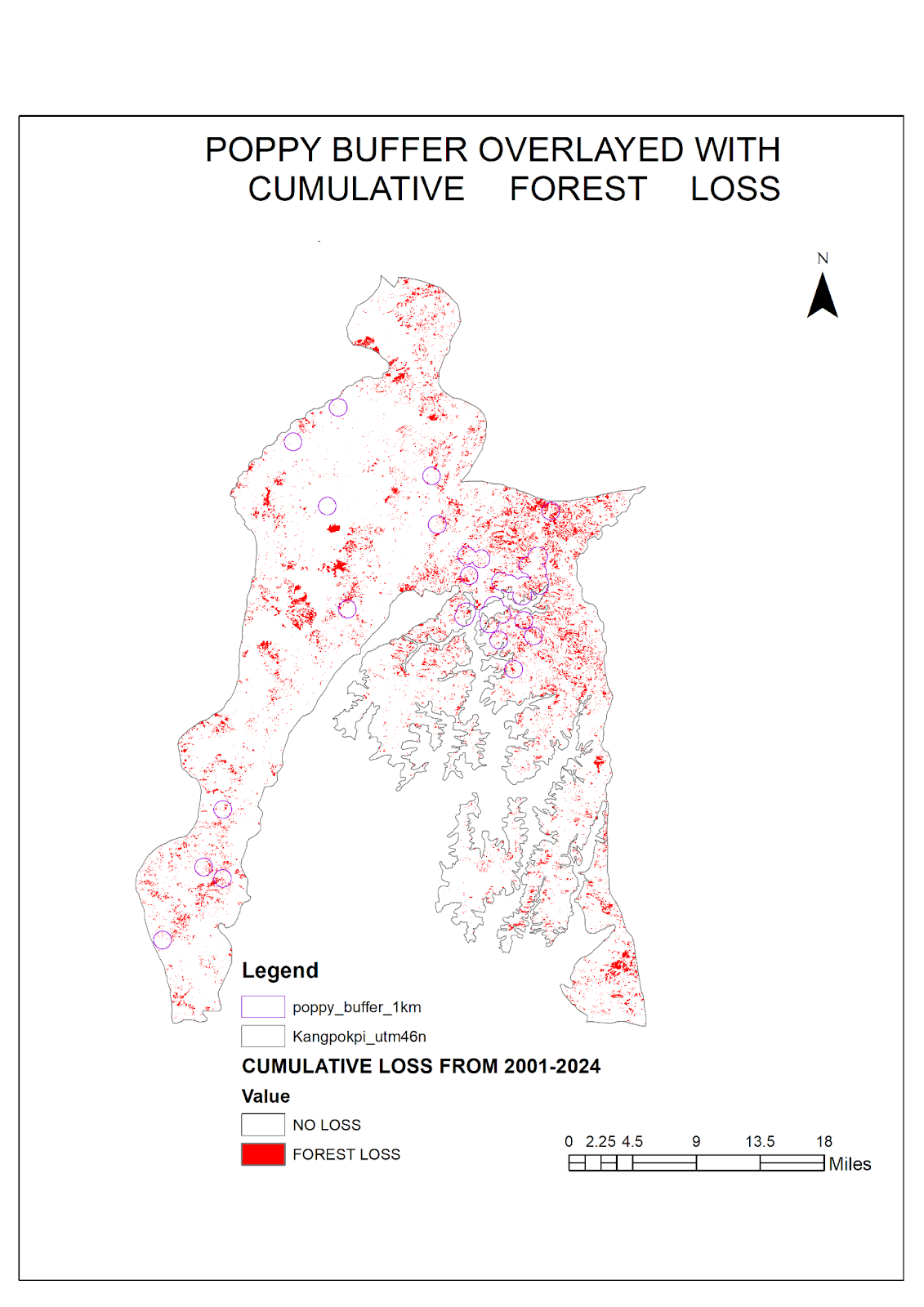

Article 14 overlaid GIS coordinates from the MARSAC report—where poppy cultivation was recorded between 2021 and 2024—with satellite data from Global Forest Watch. Developed by the World Resources Institute and partner NGOs, the dataset is widely used for forest monitoring, offering consistent, globally comparable data on tree cover and forest loss over time.

While poppy cultivation was mapped across several hill districts, our satellite investigation focused on Kangpokpi, where MARSAC detected the sharpest growth in poppy patches.

We found that poppy cultivation at these locations was preceded by deforestation patterns consistent with commercial logging, not jhum or permanent agriculture.

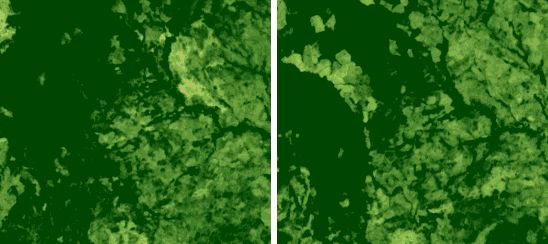

Article 14 compared the earliest clear satellite images from February 2017 with images from February 2025 for one location in Kangpokpi district identified by MARSAC as a poppy-growing site since 2021.

In 2017, the area registers as dark green, indicating dense, intact forest. By 2025, large tracts shift to light green and brown, signalling substantial forest loss.

NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), which measures vegetation vigour and canopy density, shows dark green pixels as healthy forest cover, while light green to brown patches indicate degraded vegetation, cleared land, or agriculture.

Standard colour satellite images confirm this change: what was once continuous forest now appears as exposed soil and small agricultural plots, consistent with clearing before cultivation.

A rough estimate shows about 40 hectares of forest were cleared between 2017 and 2025.

The shape and pattern of the clearings—irregular, gradual and without burn marks—point to logging or phased clearing, not shifting cultivation. This suggests the forest was being cut years before poppy appeared in government maps from 2021 to 2024, a surmise supported by a district-wide GIS analysis.

Several locations mapped for poppy cultivation were cleared well before poppy was detected, through patterns consistent with selective logging.

While our analysis does not directly attribute forest loss to logging or identify specific drivers without “ground truthing” (GIS mapping data verification through on-site observation of land use), it highlights clear patterns in satellite data. Large, continuous clearings that persist over several years and cluster in specific areas are typically linked to organised forest clearing, including logging.

A forest cover analysis of 15 locations from the MARSAC report, using Google Earth images from 2011 to 2024, shows that forest change in Manipur varies widely across locations and processes. In parts of Senapati, Kangpokpi and Ukhrul, dense forest in the early 2010s gave way to gradual clearing over several years, settling into cultivated or mixed landscapes by 2019–23.

Other sites show sudden clearing linked to roads or infrastructure, while some areas remain settlement-dominated throughout, or show only low-level disturbance rather than deforestation.

These patterns caution against blaming deforestation on a single cause and indicate that much of Manipur’s forest loss predates the recent spread of poppy cultivation.

RTIs Reveal Illegal Logging

Despite making up 90% of the state’s territory, Manipur’s hill districts are largely protected by Article 371C of India’s constitution, which allows for a Hill Areas Committee (HAC) to be set up in the state legislative assembly, which, scholars explain, is “merely reduced to a recommendatory body”.

Land in these districts continues to be controlled under customary systems, with village chiefs or councils deciding land use and sale, a structure the Manipur government itself cited last year to explain why the Forest Rights Act, 2006—which recognises and secures the customary land, resource and governance rights of traditional forest-dwelling villages over their forests—had not been implemented.

Despite Supreme Court orders (here and here) and union government rules issued in 2016 to regulate wood-based industries and tighten forest protection, local actors say commercial logging continued largely unchecked.

“During the 1990s, Manipur saw some of the worst commercial deforestation,” said Charenamei, the former MP, adding that traders exploited loopholes, while tribal chiefs, facing poverty, insurgency and ethnic conflict, had little choice but to comply.

Kaikho Mao, a timber trader from Senapati district, said he still travels deep into Tamenglong’s forests to source timber, sometimes over days-long journeys.

“In my grandfather’s time, our village had enough timber,” said Mao, tracing the depletion of timber in his area to the late 1980s.

To see how logging is monitored, Article 14 filed RTI requests with the Manipur forest department seeking district-wise data on timber extraction, transport permits and wood-based industries.

The replies reveal major gaps after government-approved “forest working plans”—based on national guidelines—in most parts of Manipur (except the Tengnoupal and Eastern Forest Division) expired in 2020.

In the Senapati district, officials reported extracting more than 2,290 cubic metres of timber from unclassed forests under working plan permissions, yet claimed that no transport passes were issued.

In Pherzawl, officials acknowledged year-wise logging even after 2020, with 1,557 cubic metres logged in 2022–23, while hundreds of transport passes were reportedly withheld due to the conflict.

In Imphal East, logging inside reserve forests was recorded as cleared under the Forest Conservation Act 1980, even though working plans had expired, alongside claims that no timber transit passes were issued.

Taken together, the RTI replies point to a system where large-scale timber extraction continued even as oversight mechanisms lapsed or contradicted one another, raising serious questions about how commercial logging in Manipur’s hill districts is monitored and regulated.

Forest Crusader Was Timber Kingpin

Besides Changoubung, former chief minister Biren Singh’s father, Gaurav Singh, regularly sourced timber from Kuki-dominated areas, according to surviving timber traders and village chiefs who confirmed doing business with Gaurav Singh.

Khupthang Haolai, who runs a kirana store in Hoikon, said he supplied timber to Singh’s family mills in the early 1990s, before Naga–Kuki violence disrupted the trade.

“I supplied timber to mills in Koirenge and Tera in Imphal,” said Haolai, adding that Singh was then a journalist and that he dealt mainly with Singh’s younger brothers, including Nongthombam Dilip Singh, who owns a veneer unit in Imphal and heads the All Manipur Veneer & Plywood Manufacturing Association.

These business ties continued for nearly two decades and ended after the 2023 conflict.

Several sources in the Imphal Valley told Article 14 that Singh later expanded timber sourcing to Myanmar, first as a minister in the Ibobi Singh government and then as chief minister after 2017. They said he cultivated ties with leaders in Myanmar’s timber-rich Sagaing region, a major source of teak, following official exchanges in 2013.

After becoming chief minister, Singh’s government approved the expansion and upgrading of sawmills into veneer and plywood units through state-level committees under the Manipur Wood-Based Industries Rules of 2018 and 2020.

These approvals came despite Supreme Court restrictions under the T N Godavarman case, which limit wood-based industries near forests and require union government clearances.

Biren Singh did not respond to Article 14’s request for a comment on violations of the Supreme Court’s orders, except with a smiley over WhatsApp.

A 2025 study on cross-border illegal logging noted a sharp rise in timber smuggling from Myanmar after 2014, driven by the growth of veneer and plywood units in the region and warned of the rapid depletion of Manipur’s very dense forests, especially in Senapati, Tamenglong and Ukhrul districts.

The RTI replies we obtained show that Manipur currently has eight veneer and plywood units and 104 registered sawmills. Four valley sawmills belong to Singh’s family, while several illegal mills in the hills were, according to his former aides in the valley, dismantled without formal inspection or closure records.

A Meitei trader displaced from Moreh said, on condition of anonymity, that only a few traders can operate now, often with the help of Pangals, as local Muslims are known in Manipur. Before the violence, Meiteis in Moreh traded extensively with Myanmar, particularly in betel nuts and timber.

The trader rejected claims of an exclusive lobby linked to former chief minister Biren Singh, saying anyone with the “right help and connections” could enter the illegal timber trade.

He said Singh’s brother ran a large sawmill with the United Kuki Liberation Front in Serou, but added this did not necessarily give others fewer opportunities. The sawmill was burnt down in 2023 after ethnic violence broke out.

However, Devabrata Singh, former working president of the Indian National Congress party in Manipur, alleged that other traders were required to pay him a share. “On average, Biren (Singh) moved over 300 trucks of veneer every month, mostly from Myanmar,” he told Article 14.

Asked for comment, Biren Singh did not address the accusation.

Timber Is King, Despite Separation

Manipur remains sharply divided along ethnic and geographic lines, with new tensions flaring recently.

Kuki Zo communities cannot enter the valley, where most infrastructure and markets are located, while Meiteis—except Meitei Muslims—avoid National Highway-2, which passes through Kuki-dominated Kangpokpi before entering Naga-dominated Senapati.

Despite these informal restrictions, several local sources said many businesses, such as timber, continue largely unaffected. Kuki Zo insurgent groups, some of whose suspension-of-operations agreements were renewed last year, are known to collect informal road taxes from vehicles on the highway.

“I know someone who still collects timber locally and takes it to Imphal,” said a retired forest official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “He’s protected. If one link breaks, the whole business stops—so they move together.”

Article 14 reviewed videos showing timber trucks crossing district boundaries into the valley, though Kangpokpi police claimed no timber had moved since the conflict began.

In the Naga hill districts, such as Senapati, considered relatively neutral grounds for both Kuki Zo and Meitei communities, timber trader Kaikho said tribal entrepreneurs remain marginalised. His sawmill application, along with seven others, has been pending for years.

RTI replies show that no wood-based industries operate in Senapati, while most registered units are concentrated in the valley.

Still, Kaikho spoke with resignation rather than anger about decades of deforestation. “We sold trees to survive,” he said. “The forests are gone, but villages didn’t gain much.”

Kuki Zo activists acknowledge that accusations of logging and poppy cultivation are not baseless. At the same time, some villages are shifting towards alternatives—multi-crop farming and bans on commercial logging.

“You can’t ask people to stop jhum or poppy without giving alternatives,” said Misao, pointing to repeated failures of government support when farmers tried to shift crops.

Misao warned that poppy cultivation causes long-term damage. “When it rains, chemicals flow into rivers,” he said. “We drink that water. It may not kill us immediately, but it will slowly.”

In Chalwa village, commercial logging has been banned, said village chief Thangminlen Kipgen. The village now focuses on organic crops such as turmeric, ginger and oranges—products replaced by poppy elsewhere due to lack of markets.

“Monocropping exists because farmers are at the mercy of markets,” said Kipgen, who heads the Kuki Inpi (an apex tribal body that decides customary laws and practices) in Sadar Hills. He said demands for price support, storage and processing were ignored.

“Biren did nothing,” said Kipgen. “He only built roads for the timber trade.”

With GIS inputs from Madhava Krishnan.

(Makepeace Sitlhou is an independent journalist and producer based in New Delhi. Greeshma Kuthar is an independent journalist and lawyer based in Chennai.)

This story was produced with support from Earth Journalism Network’s Investigative Story Grant and Training Program for Indigenous Journalists.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.