New Delhi: The essence of client-attorney privilege is that the law regards a lawyer as an extension of his client. The law guarantees a person protection against self-incrimination, and it follows that his lawyer is also not permitted to incriminate that person by disclosing communication or correspondence with a client to any third party, including the court.

A lawyer is not a mere mouthpiece of a client, but is nevertheless a mouthpiece. The lawyer does nothing more than give a legal language of rights and obligations to the factual narrative that a client may present, normally accepted on face value.

Since the law regards a lawyer and a client to be inseparable, the law protects their relationship even more rigorously than any other relationship. The client-attorney privilege aims to create a 'zone of privacy', within which a lawyer and a client can have an unfettered conversation and exchange correspondence without prying eyes.

Such protected communication is required to be excluded from evidence—at the heart of the privilege is not the fact that it would be excluded from consideration but that it would never be disclosed.

The client-attorney privilege comprises two aspects: one that deals with communications that seek or provide legal advice; and other aspects that deal with documents prepared in the context of litigation, whether existing or anticipated.

In India, both are protected.

In the context of documents prepared for litigation, one of the agreed basis for providing client-attorney privilege is that each party should be free to prepare his or her case as fully as possible without the risk that the opponent will be able to recover the material so generated.

Client-Attorney Privilege And Public Interest

There is no doubt that client-attorney privilege, whether dealing with disclosures to seek legal advice or those concerning communications in the context of litigation, is repugnant to the public interest inherent in the court's duty to study all material to arrive at the truth.

However, outweighing the said public interest are, firstly, the public interest in protecting the individual's rights to make full disclosure to a lawyer to seek proper legal advice; and secondly, the right of the individual to be protected from prying eyes of the opponent, be it a private citizen or any governmental agency.

In India, section 126 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, extends client-attorney privilege only to practising lawyers and to independent in-house lawyers, on the unsaid basis that as a professional, the only allegiance of advocates is to the rule of law.

Of course, there are exceptions to client-attorney privilege.

Extracted below are two examples from section 126 of the Evidence Act do a fine job of explaining the difference and their context:

(a) A, a client, says to B, an attorney—"I have committed forgery, and I wish you to defend me". As the defence of a man known to be guilty is not a criminal purpose, this communication is protected from disclosure.

(b) A, a client, says to B, an attorney—"I wish to obtain possession of property by the use of a forged deed on which I request you to sue". This communication, being made in furtherance of a criminal purpose, is not protected from disclosure.

It is clear from these examples that it is not open to plead client-attorney privilege on any communication if the communication tends to make the attorney an accomplice in any crime that is being planned.

It is also clear from these examples that the distinction between the two is very fine, and it is doubtful whether ordinary Indian clients would be able to articulate their facts as sharply as is done in the carefully drafted examples in the Evidence Act.

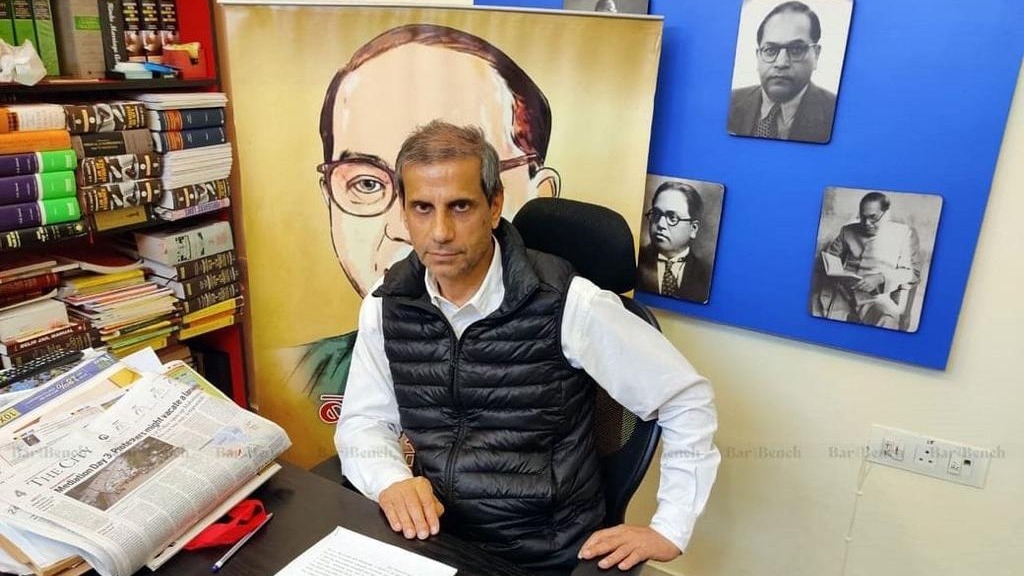

What Is Wrong With Mehmood Pracha's Case?

Many of my colleagues at the bar and several bar associations are hesitant to take a stand against the authorized search at the office of advocates Mehmood Pracha and Javed Ali by the Special Cell of the Delhi Police because of the understanding that a lawyer who is an accused in a criminal case cannot seek refuge under the doctrine of client-attorney privilege.

[The Special Cell registered FIR No. 212 /2020 under eight sections of the Indian Penal Code, 1870, against Pracha.]

To understand this argument, let us understand the context of the FIR and the nature of the offences mentioned.

Pracha is amongst several lawyers representing several victims of the February 2020 Delhi riots, in which 53 people died. Pracha continues to defend the victims, who allege, inter alia, criminal use of force by the police or under their watch.

Many young lawyers who sought to assist protestors against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, in February 2020 were themselves detained and allegedly assaulted by the Delhi police. They later demanded action against the police.

Many lawyers who represented riot victims initially later alleged that they were under surveillance. The charge-sheet in FIR No. 59 dated 6 March 2020 PS Crime Branch has several pages that detail the coordinated help extended by lawyers that were providing legal aid to CAA protestors, though they have not been made accused yet—signifying that the police regard performance professional duty by lawyers— a crime. In another reported case, a lawyer was even also detained and tortured.

As the media reported, the Special Cell's FIR No. 212/2020 was lodged against Pracha after observations from the court premised on two aspects.

One, that his office filed an affidavit in support of a bail application which was notarized by a lawyer who died in 2017, suggesting allegations of forgery. Two, that complainant Irshad Ali, whose shop was looted the Delhi pogrom 2020 in Dayalpur had failed to identify the accused named in his complaint—and later blamed Pracha for trying to wrongly implicate certain persons.

It appears Ali has not denied that he signed this complaint. In this context, the FIR alleges crimes under the following provisions of the IPC: 182 (false information, with intent to cause a public servant to use his lawful power to the injury of another person); 193 (punishment for false evidence); 420 ( cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property); 468 (forgery for purpose of cheating); 471 (using as genuine a forged document or electronic record); 472 (making or possessing counterfeit seal, etc. with intent to commit forgery punishable under section 467); 473 (making or possessing counterfeit seal, etc. with intent to commit forgery punishable otherwise); and 120B (punishment of criminal conspiracy).

The search of Pracha's office was authorised by a magistrate, who appears to have permitted only a narrow search. The warrant read: “It has been made to appear (sic) to me that incriminating documents comprising false complaint and meta-data of outbox of email account which was used to send incriminating documents are essential to the investigation of FIR No. 212/20 of Police station special cell, New Delhi.."

Thus, the warrant permitted a specific search "…wherever they may be found whether in computer or in the office/premise of Sh. Mehmood Pracha", and not an omnibus search that the police are used to.

A Lawful Or Unlawful Search?

Whether it was lawful for the police officer carrying out the search to 'seize' a host of data from Pracha's computer when the warrant was narrow and permitted the search of documents relevant to the case under investigation is an issue that is at the core of the debate.

There is also a legal issue of whether the law would allow the investigating officer to examine all privileged material himself to segregate what may be relevant for FIR No. 212/2020 (and still exclude what is legally privileged within that case), or should each document be judicially examined to keep it away from prying eyes of the police?

As regards the forged signature on the bail application, the signature of a dead-lawyer on a bail application, the investigation ought to be purely based on the false document (presumably already seized), which is the bail application.

It does not appear logical that it would require any further information except to retrieve the soft copy of the bail application if filed electronically by email.

As regards Ali’s statement, this is not the first time in India that a complainant or an eye-witness has turned hostile. We are far too familiar with the trial in the murder of Jessica Lal and the now a famous legal adage: "No one killed Jessica".

There can be many reasons for a victim or a witness failing to identify an accused—and the truth is only one of them.

Any drafts of Ali's complaint exchanged within a lawyer's office or with his clients are, perhaps, issues that could possibly fall within the ambit of the search warrant, and should be specifically identifiable from other cases.

However, it appears officers of the Special Cell searched Pracha’s entire office and took away a "large amount of content without disclosing what information they were accessing or taking with them" and without first ascertaining their relevance to FIR No. 212/2020.

When the police knew what they were looking for, and the warrant was specific, there was no occasion to take away a mountain of information from a lawyers' office.

An Attempt At Intimidation

Today, the Delhi Police have large amounts of data from a lawyers' office including documents, research, information, and communications of Pracha's other clients where Delhi police is the opposite party. This information may also include Pracha’s correspondence with other lawyers in relation to other co-accused or in other litigation and in addition to any possible data connected to FIR No. 212 /2020.

From the information in the public domain, it is also not certain that copies of the data were made, as hash values and system metadata were not available. Hash value is a result of a calculation (hash algorithm) that could be performed on a string of text, electronic file or entire hard drive's contents, and it changes every time the contents are changed (or even accessed changing some characteristics of any file). It is like a super sensitive finger-print of an electronic file.

What is untenable in Pracha's case is not that his office was searched but that legally privileged data in relation to other clients and other cases pertaining to Delhi Police have been taken away by them. What they could do directly, the police may have achieved indirectly—without any immediate accountability.

One may be able to argue the nature of allegations against Pracha may well, in law, justify a limited search after an application seeking production of documents has failed. However, mere pendency of FIR No. 212 of 2020 against Pracha cannot justify the destruction of the constitutionally promised “zone of privacy” between a lawyer and his client generally.

To an outsider, this is an attempt at intimidation, as the Supreme Court Bar Association has acknowledged.

If one ignores for a moment that there was an observation by the court in Pracha's case, registering an FIR against a lawyer—for something as simple as arguing with a policeman (as the police did later with Pracha)—is within the police domain.

An ordinary citizen may take months together to get an FIR lodged, but for the police, it is half a minute's job to lodge FIR against a lawyer or anyone else. Thereafter, the police can make voyeuristic trips to the office of an accused lawyer to retrieve case files, notes, correspondence, details of fees received, his phone records and the like.

Because Pracha is well known, a warrant was obtained. For other lesser known lawyers, even that due process may not be followed.

It is for this reason that Pracha's case, despite its peculiar facts, is a clarion call before the death knell of the rule of law in India.

Why The Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas Precedent Is Different

It appears that many have also drawn parity with the Nirav Modi case in 2019, when a law firm was raided by the CBI. Previously in 2019, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) had raided the office of M/s Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, a law firm seeking to recover documents provided by their client (Nirav Modi & Co.)

A few days after the search "Cyril Amarchand employees had brought a tempo truck containing cartons of documents to the CBI office", as Bar And Bench reported, and their partners had disclosed emails between them and Modi.

The CBI also froze M/s Cyril Amarchand’s bank account, which after court intervention was reactivated, except for Rs 2.12 crore received as legal fees. It appears that M/s Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas did not assert their right in the same manner as Pracha is doing now.

Indeed, it appears from the article that the firm had handed over Modi's documents to CBI whilst also recording the conduct of their client. To my mind, there cannot be a comparison between the two as in one case, privilege is asserted and in the other it is waived. It is also a legal question whether the firm could waive the privilege, for the privilege belongs for the benefit of the client.

Having said that, the attachment of legal fees received by M/s Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas from Nirav Modi & Group is unacceptable and cannot be regarded as proceeds of crime. If that were the case, legal fees given to any lawyer who has ever appeared for any person convicted of a crime (in case of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, charged for a predicate offence) could be attached. And, that perhaps is going to be the next tool to harass lawyers who take up cases against the Government or judges who have appeared in the past against such persons.

It is one thing to allege that a lawyer is co-accused in layering or integration of proceeds of a crime and another is to attach their bank accounts because it has reasonably standard legal fees receipts from a person later accused of a crime.

What goes on between a lawyer and a client must remain only between the two. The State has no legitimate interest in uncovering the communication or correspondence between the two as it serves no fruitful purpose.

As governments and courts have protected medical professionals extending medical help from reprisals by patients' families, so, too, should they protect lawyers extending professional help to victims of crimes, especially where the role of the police is under suspicion.

No one should forget that tomorrow, even they may need lawyers and a zone of privacy.

(Talha Abdul Rahman is a graduate of the National University of Law, Hyderabad, and University of Oxford, UK. He was formerly a junior standing counsel with the Income Tax Department and the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence. He practices law in the Delhi region)