Climate activist Greta Thunberg's viral Twitter spat with former kickboxer Andrew Tate, more famously known as a misogynistic influencer, followed by his arrest in a human trafficking case, has drawn attention to the toxic world of the men's rights movement or MRM.

Tate, a popular men’s rights activist in the movement, was banned from all the major social media platforms for his racist and provocatively outrageous content promoting derogatory views against women, rape culture, and sexual violence. His Twitter account was reinstated after Elon Musk took charge of the platform as the CEO promising to uphold free speech. A British advocacy group warned Tate’s online presence was a “genuine threat to young men, radicalising them towards extremism, misogyny, racism, and homophobia”.

The MRM emerged in the 1970s in the United States as a reaction to the growing feminist wave. The movement argued that men were discriminated against when it came to family rights, divorce, child custody, alimony and cases of domestic violence, among others. It has since become controversial for propagating regressive attitudes toward women, bashing feminists, and portraying men as victims of feminism. The MRM has also been flagged off for being notoriously dangerous, as certain MRAs were found to be linked to alt-right extremist movements.

Today, the movement has a massive presence online in the form of varied “misogynistic communities” known as the manosphere ranging from anti-feminists to MRAs and incels.

A study by researchers Sheyril Agarwal, Urvashi Patel, and Joyojeet Pal from the University of Michigan shows. “An anti-feminist movement has grown in India online since the MeToo movement,” they say.

The MRM in India can be traced to a single man’s crusade against “blackmailing and harassing” of husbands by their wives following reforms in the domestic violence and dowry laws in the 1980s. A victim of a bad marriage, Supreme Court lawyer Ram Prakash Chugh started a support group for husbands called Patni Atyachar Virodhi Morcha (Union against persecution by wives) and formed an organisation called “Men Cell”, also known as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Husbands to help men fight charges of domestic violence, dowry and harassment in the court. He believed that women abused the process of law by moving the court in domestic matters and the courts tended to rule in their favour.

Chugh’s ideology inspired similar groups across the country.

In the last decade, these scattered groups have established a well-organised network holding public meetings, annual conferences and publicity stunts like a pooja for the liberation of demonic evil women. Their online presence has also grown from Yahoo chat rooms to a coordinated network of accounts championing men’s rights while spewing hatred against women.

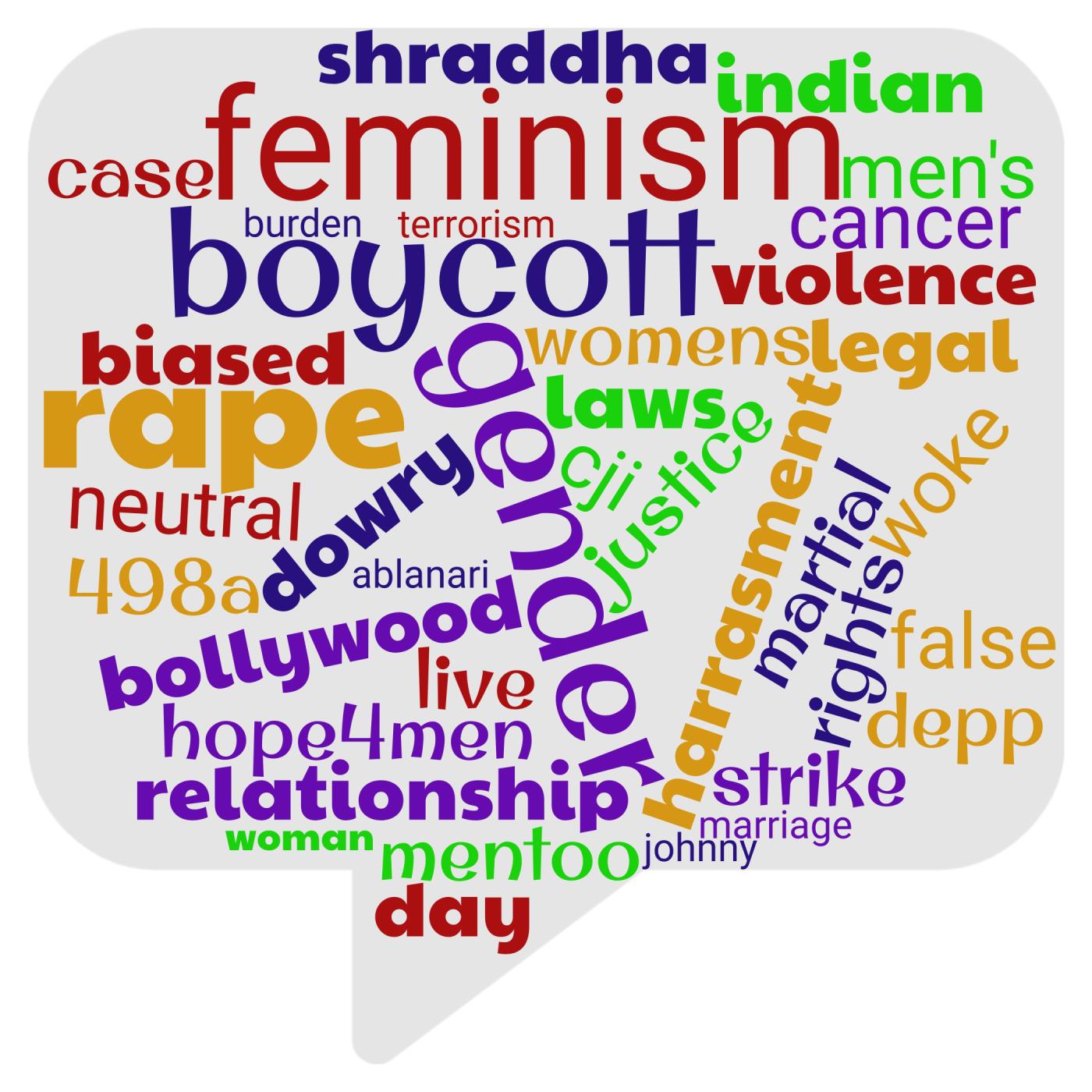

The study by researchers Agarwal, Patel and Pal shows these MRA accounts are behind some of the viral hashtags on Indian social media: #boycottmarriage, #AblaNaariSyndrome, #मर्दअसुरक्षितहै, and #MensLivesMatter. They are also among the worst trolls indulging in misogynistic comments and threatening women journalists, lawyers, politicians and actors, or any outspoken figures.

Violence against women remains steadfast and has seen a year-on-year rise. Crimes against women grew by 15.3% in 2021, particularly domestic violence, according to the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) data.

The Indian MRA community is synced with the global discourses centred around women and gives its own take on social media on trending issues. For example, when allegations of #MeToo emerged in India, the MRA accounts punctured holes, ridiculed accusations of sexual harassment in the workplace as “false claims”, and trended the hashtag #MenToo. More recently, during the defamation trial of Hollywood couple Amber Heard and Johnny Depp, they supported Depp in the domestic violence case and castigated Heard as #AblaNari.

To gauge the impact and reach of the Indian MRA community, researchers Agarwal, Patel and Pal examined their activities on Twitter, sifting through a massive sample of 10,74,999 tweets over a one-year period from November 2021 to 2022. They tracked reactions and campaigns of the MRA at the time of the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment recognising marital rape and including forced sexual assault in abortion laws, the appointment of DY Chandrachud, who delivered the marital rape judgment as the Chief Justice of India, the grisly murder of Shraddha Walkar by her boyfriend Aftab Poonawala and actor Richa Chadha’s statement on Galwan interpreted to be mocking the Indian army. The researchers found the anti-feminist narratives disseminated by the MRAs, intersected with the Hindutva rhetoric on Islamophobia and its campaign against boycotting Bollywood, even if the MRAs might not directly identify themselves as right-wing.

Although the MRM has a niche presence with limited influence in India, the study finds the movement is evolving online, where it is a big driver of virulent and hateful anti-feminist content.

Article 14 spoke with researchers Pal and Agarwal on the MRM, its online community and why its discourse should be a cause for concern.

What is the Indian MRA movement and its ideology? Is it interconnected with the global men’s rights movement that sees men as an oppressed group?

Joyojeet Pal: The global MRA movement has directly taken aim at the notion of “grievance feminism”. The movement argues that seeking institutional protection of women over men are flawed and contrary to the idea of absolute equality. It stands against the notion of structural or cultural elements of inequality as something that privileges men, and rejects western feminism. The Indian MRM has traditionally focused on judicial activism around the perceived preferential treatment of women in cases involving Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (cruelty). In particular, provisions such as the arrest of husbands and family members around domestic violence cases and financial aspects of alimony in divorce cases have been central to the MRA movement in India. An important inflection point in the movement was a 2014 report by the Delhi Commission of Women which claimed that the majority of rape cases filed in Delhi were false (in large part due to consensual sex criminalized by family members), which led to the then women and child development minister Maneka Gandhi proposing the NCW consider ways to hear allegations of false complaints and harassment by men.

There are a number of men’s rights organisations throughout India, many meet in person and have existed long before social media (or the internet). The MRAs both have a physical network, and practicing lawyers who typically work through referrals. There are also prominent MRA individuals who offer consulting services to men who feel victimized and offer them free counselling about approaches they can take to fight their cases.

What are the prominent individual and group accounts championing the anti-feminist movement and men’s rights?

Joyojeet Pal: Supreme Court lawyer Ram Prakash Chugh has been considered as a key driver in the early days of organising around the issue. “Save Indian Family” has been an important group that has pre-dated the social media era.

Sheyril Agarwal: Filmmaker Deepika Narayan Bhardwaj and relationship counsellor Monica Garkhel are leading women rallying for men’s rights; legal consultant Shonee Kapoor who offers aid to men on 498A, rape and matrimonial issues , and MRA Chetan are other known profiles in the movement.

Is there a typical profile of the MRA supporter? Does it also include women?

Joyojeet Pal: A majority of MRA supporters on Twitter self-identify as middle class vocations such as engineering, tech, medicine, and students. Srimati Basu’s work has shown that most MRAs were not themselves working through divorces, but rather were individuals with anxieties about economic rights in marriage, intergenerational property issues, and more broadly, on the notion of gender in society.

In general, the overwhelming majority tend to be men, but some of the most engaged public statements come from female influencers in the network. It is also common that photographs of MRAs meeting in public will often include one or a few female persons. The existence of female members in public photographs gives more credibility to the organisations.

What drives these accounts to propagate misogynistic content and what broad topics do they center their posts on?

Sheyril Agarwal: A major theme of MRAs is the alleged false cases filed against men. There's also hostility towards feminism and wokeness as a whole. Legal proceedings initiated by women against husbands are considered as an attack on Indian family values, traditions, and marriage. Some posts offer advice to other young men in India, warning them against getting exploited by women.

The MRA spreads fake news and misinformation against women on rape, dowry-related atrocities, and sexual harassment, projecting them as false cases to frame men. Do you think the MRA’s activities damage and discredit the women’s rights movement in India?

Joyojeet Pal: The MRM is foundationally based on the idea that women take advantage of divorce-related laws, and by extension it argues that a subset of women are untrustworthy. Their logic is thus to bring doubt to the testimonies of women. The discourse MRAs promote is to vilify the accusations of a woman a priori. Thus, for instance, when the Depp-Heard civil litigation began, the MRAs started to support Depp online, well before the outcome of the case.

It cannot be said that these successfully damage or discredit the women’s right’s movement – for one, very few younger women buy into the ideas that MRAs put out, nor are there any mainstream celebrities or politicians who openly support the ideas put forth by MRAs. This could largely be due to the fact that most MRA content online tends to be directly oppositional to most forms of women’s rights and argues for a traditionalist society. For instance, the name of the key MRA organisation is Save Indian Family Foundation, which by extension subordinates women’s rights to that of the notion of family. Most of this suggests that MRAs are still largely seen as a fringe cause to be associated with. Perhaps the only sign that there is a dent in the women’s rights movement in India through MRAs’ activities online is that more people feel afraid to lend their voice to causes that may being about aggressive reactions online. In part, the association of feminism with secular liberalism in India has ended up enabling a broader assemblage of negative rhetoric being aimed at it.

Ironically, there is also a necessarily masculinist reason for why these have been unsuccessful to get any widespread traction—to admit that one belongs to an oppressed lot, one must accept first that one is ‘oppressable’ to begin with, which in and of itself arguably rankles macho sensibilities.

You have outlined the anti-feminist discourse on Twitter via four case studies: the killing of Shraddha Walkar, actor Richa Chaddha’s statement on Galwan, the Supreme Court judgment on marital rape, and DY Chandrachud’s appointment as the chief justice. What are your main observations?

Joyojeet Pal: In the four cases, we found instances of coordinated viral tweeting. In CJI Chandrachud’s case, there was an organized attempt to undermine his credibility because of his feminist positions on certain judgments. At the time of his appointment as a CJI, we saw anti-CJI content trending, with quote-tweeted messages on his positions on women’s issues and personal attacks including on his son. A lot of these posts were also engaged in by pro-Hindutva accounts using #NotMyCJI #LegalTerrorism hashtags.

Shraddha Walker’s murder was falsely propagated as a case of “love jihad” rather than domestic violence. The overall trend was victim blaming.

The big viral tweet among MRAs came from pro-Hindutva American influencer Renee Lynn which absolved men and presented the case as solely related to Shraddha’s Hindu faith. The MRAs also repeatedly shamed Shraddha on her religion, parents/family norms, “woke feminism”, liberalism and live in relationships.

Actor Richa Chadha’s tweet on Galwan, evoked highly misogynistic replies even advocating violence against her. One of the top drivers for the MRA community was actor Akshay Kumar’s tweet against her, which unleashed flurry of co-ordinated tweets.

Sheyril Agarwal: We find that the use of humour, sarcasm and memefication around feminism, relationships is a consistent theme. We see the MRAs hopping on to viral events which may or may not be related to their cause. Often, they'll add a trending hashtag to their tweets with no relation to the tweet content, hoping to get discovered. There's heavy use of pop culture references that look like fan art but contain anti-feminist messaging. Tweets highlighting crimes against men that link to some external news site were also quite common. Some posts make use of old stereotypes like "women are gold diggers" to build a narrative against women.

The anti-feminist narratives use humor particularly through memes to target women. Do these jokes promote rape culture, sexual violence and misogyny? What other means do they use as part of their vitriolic messaging?

Joyojeet Pal: The two main approaches that we see in online MRA content are the use of sarcasm and the evocation of anger against women. These are often done by highlighting certain messages from women that show them in poor light, or by presenting a male partner’s perspective in a spousal dispute. The majority of messages that are related to rape tend to be around marital rape and false rape allegations. Some of these messages suggest that most rape accusations are exaggerated. Here are a few examples.

The second element of vitriolic messaging is seen in body-shaming, mostly driven by the underlying notion that a woman who is a feminist is physically unattractive. This is also extended to males, through the use of “simp” as an insult aimed at men who take on feminist causes.

In the research paper, you mention that the MRA is self-contained and rarely gets attention from big accounts. Why is it then important to focus on their narratives?

Joyojeet Pal: The core MRA community is self-contained, but they often play an important role in promoting a discourse that has a broader audience, which is why we showed the impact they had on the activism against the Chief Justice of India. The MRA community is in some ways similar to other radicalised communities that comes together under the umbrella of a shared cause (in this case anti-feminism), but the nature of Twitter as a medium gives them a sense of the other communities that they can ally with.

So, what matters about the MRA community is that it can move in unison, and as a result quickly extend its collective support to new causes. The MRA community thus proposes itself as an upholder of tradition and the unified family structure in India. By extension, these narratives matter beyond their core communities when they are able to normalize themselves since they present themselves as defenders of normative values.

It is also important to focus on their narratives since they offer a means of community for disaffected males in or out of relationships, who are told here that it is woke women and the men who stand by them, as people to blame for their lot. This has long-term consequences for the ability of these men to have fruitful relationships with their partners, and more importantly, can expose women to people who have been groomed to think of women as having unreasonable expectations and malintent.

Can you name some popular accounts of women who are targeted by the MRA?

Joyojeet Pal: The most prominent women consistently trolled by the MRA communities from our data were Supreme Court Advocate Karuna Nundy, actor Swara Bhaskar, and television anchors Barkha Dutt and Faye D’Souza.

Does the MRM qualify as extremist and its narratives as hate speech?

Joyojeet Pal: It qualifies as hate speech because the overwhelming number of messages we see do not just stop at defending men (with or without evidentiary drivers), but go out of their way to attack a certain form of womanhood. In this sense, it is extremist in the same way that victim blaming is, for instance when a woman’s dress or demeanour is blamed for a male attack, because the perpetrator is given an excuse for their behaviour.

How can online abuse by misogynistic content be countered ?

Joyojeet Pal: The best way for this to be countered is for more men to come out and support feminist causes, and counter or engage their contacts who promote MRA content. It is also incumbent upon more influencers, politicians, and average citizens on social media to call out bad behavior instead of assuming it will lead to trolling.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.

(Shweta Desai is an independent journalist and researcher based in Mumbai.)