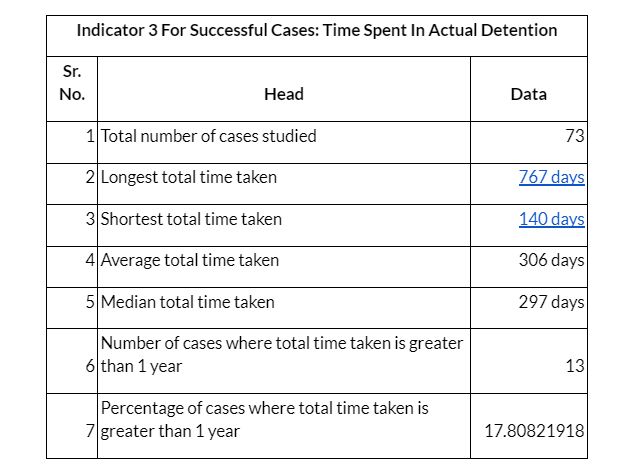

Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh: Those detained but wrongfully held under India’s restrictive preventive detention law, the National Security Act (NSA) 1980, in Uttar Pradesh spent 306 days in jail before their cases were quashed and they were set free by the Allahabad High Court

In general detenus, innocent or otherwise, spent about 76% of their maximum period of detention under India’s restrictive preventive detention law, the National Security Act (NSA) 1980, before their petitions were finally disposed of.

These are the findings of an empirical study of 101 NSA cases in the Allahabad High Court that we conducted using data over a nine-year period, between 2010 to 2019.

Our other main findings:

–On average, the Allahabad High Court gave a decision after 276 days after the date of the detention order

–On average, the Allahabad High Court gave a decision after 170 days from the High Court was moved, though habeas corpus petitions

–On average, a detenu spent 314 days (the maximum was 767) in detention before either a decision by the Allahabad High Court or the maximum possible period of detention lapsed

–In 18% of all cases, the time spent by the detenu in actual detention was greater than a year, the maximum allowed under the NSA

–The police made arrests after criminal complaints, offences, or detained them only on suspicion. When detenus struggled to post bail, a detention order under the NSA was passed, prolonging detention

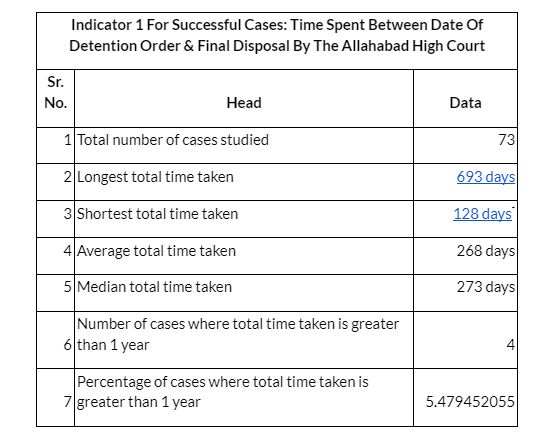

We also studied 73 ‘successful cases’, where the Allahabad High Court quashed detention orders and set detenus free. Our findings in those cases:

–On average, the Court gave its decision after 268 days, calculated from the date of the detention order.

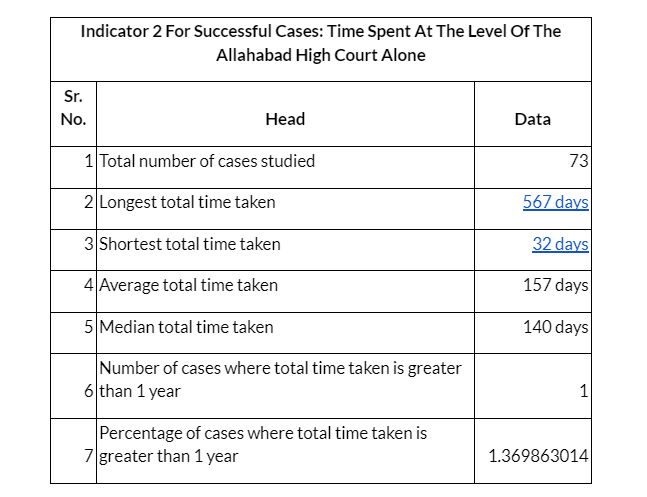

–In ‘successful’ cases, on average, the Court gave its decision in 157 days, calculated from the date the Court was moved, that is, the date the habeas corpus petition was filed.

Despite the consistent advocacy (here, here and here) of the Supreme Court on the prompt disposal of habeas corpus petitions, our data reveal that in practice, detenus spent the major part of their maximum possible detention period in jail, whether guilty or not.

Habeas Corpus: Not The Remedy It Should Be

The purpose of this investigation was to analyse how effectively the judiciary guards the personal liberty of citizens against arbitrary executive action in Uttar Pradesh.

We wanted to answer the broad question of whether it was meaningful for an individual placed under illegal preventive detention to move the Allahabad High Court under Article 226 for a writ of habeas corpus—literally, in Latin, to produce the body.

The answer from the findings of our study: the habeas corpus is not the remedy it was meant to be.

The object of habeas corpus proceedings to bring accountability to such preventive detentions, “to make them expeditious”—as the Supreme Court said in 1959 in the case of Ranjit Singh vs The State Of Punjab—is almost, if not completely, frustrated.

The NSA allows the union or state governments to detain suspects without charge for up to a year, to prevent them “from acting in any manner prejudicial to the defence of India, the relations of India with foreign powers, or the security of India”.

People may also be detained to prevent them “from acting in any manner prejudicial to the security of the State or from acting in any manner prejudicial to the maintenance of Public order or from acting in any manner prejudicial to the maintenance of supplies and services essential to the community”.

Once such a detention is made, the suspect loses certain rights, for example, the right to consult a legal practitioner of his choice. Article 22(3) of the Constitution excepts a preventively detained person from the Constitutional protections guaranteed by Articles 22(1) & 22(2) to an arrested person which include the right to a legal practitioner. The right to bail may also be affected. In fact, our study found that the State often passed detention orders against an already arrested person with the sole motive to not let the person avail his right to bail in the case(s) going on against him.

Preventive Detention Obstructs Fairness, Justice

Preventive detention laws continue to be an obstacle to established principles of justice and fairness in India, owing to the lack of trial or judicial oversight and the amount of latitude available to the executive.

Some examples of preventive detention laws, apart from the NSA are: the Public Safety Act, 1978, of Jammu and Kashmir; The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967; The Gujarat Prevention of Anti-social Activities Act, 1985; State-Specific Goonda Laws such as in Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

Various preventive detention laws have survived the test of constitutionality (here, here and here) and this is why courts have limited their interference to quashing detention orders in individual cases. The court does this on the limited grounds of procedural safeguards, such as an absence of relevant material before the detaining authority, or if there is an unjustified delay in deciding the detenue’s representation.

The only recourse for an individual placed under such preventive detention is a writ of habeas corpus under Article 32 or Article 226 of the Constitution.

If the detention does not meet the limited procedural safeguards contained in the relevant Act, the Court may declare it as illegal and issue a writ of habeas corpus for the release of the detenu.

All preventive detention laws in India have a maximum detention period, and even if the detention is otherwise illegal, the person must be released after this period.

This is why it is important to analyse how prompt the courts are in deciding habeas corpus petitions so they do not become infructuous or pointless when they drag on.

Why We Chose Uttar Pradesh

Our study was inspired by a July 2020 paper by Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj on the average disposal rate of habeas corpus petitions in preventive detention matters with respect to the Supreme Court.

Bhardwaj found that the habeas corpus was reduced to a “meaningless remedy” in most cases. He came to this conclusion after noting that in at least 36% of the habeas corpus petitions before the Supreme Court in cases of preventive detention, the Supreme Court had delivered its judgment after the maximum period of detention under the statute had already passed. He concluded, therefore, that the Supreme Court’s role in rendering the writ of habeas corpus meaningless has been significant.

Although each High Court must be studied individually, we began with the Allahabad High Court in the present study owing to the fact that Uttar Pradesh is India’s most populated state with more than 200 million people.

The 177th Report of the Law Commission, issued in 2001, noted that in Uttar Pradesh 73,634 arrests were made for substantive offences—a criminal act that has been committed—compared to 479,404 preventive arrests made for a criminal act that the police suspect may be committed.

These numbers also seem to grant some legitimacy to the criticism (here, and here) of the Uttar Pradesh government as using preventive detention laws arbitrarily, and among other ends, to curb dissent.

Only judgments reported on SCC Online, a legal research website, were used for this study.

Other places such judgements are available were the website of the Allahabad High Court and other legal research databases, such as Manupatra, LexisNexis, or Indian Kanoon. We chose SCC Online primarily because we had access to it, and because it has a 'phrase search' tool, which others do not.

We could not study these judgments directly from the Allahabad High Court website, since the number of such cases was impossible to handle. A right-to-information query we filed in 2021, revealed that over 10,000 judgments were delivered in habeas corpus cases between 2010 & 2020 by the Allahabad Bench only.

Of 602 search results obtained after running a Boolean phrase search for 'habeas corpus' on SCC Online and limiting the search results to the Allahabad High Court for the period 2010-2019, we studied 101 cases of preventive detention under the NSA.

One Constitution Bench judgement was excluded because it pertained to the year 2002, and the detenu had been released earlier. Two more judgments were excluded because the reported judgments in these cases as well as the orders available on the High Court's website had logically inconsistent dates.

How Our Analysis Unfolded

We analysed the data using three ‘indicators’.

Indicator (1) was the period after the passing of a detention order and its final disposal by the High Court. This indicator demonstrates if it is meaningful to challenge a detention order before the Allahabad High Court.

Indicator (2) is the time taken to hear a detention order in the Allahabad High Court alone.

Indicator (3) deals with the question: how long did the detenu actually spend in detention? The dates important for this analysis were: (i) the date of the detention order or the date of actual detention, whichever was earlier, and (ii) the date of decision by the Allahabad High Court or the date when the maximum period of detention lapsed, whichever was earlier.

Despite the apparent similarity, there is a difference between Indicators 1 & 3: in almost all of the cases of preventive detention that we studied, the date of detention order under the NSA was not the same as the date when the detenu was actually arrested or taken into custody.

Indicator (1) was related to the date when the detention order was passed, while Indicator (3) was related to the actual date of detention. While Indicator (1) reflected the delay that existed on papers and court files, Indicator (3) provided a more human context to the other data.

There were times when a detenu’s arrest and the passing of the detention order were not on the same date. To understand this better, here are the three possible scenarios:

Of the 101 cases we studied, in no case was it explicitly mentioned that the detenu had been arrested after the detention order was passed. In cases where judgements and orders were silent about the actual date of arrest, we assumed that the detenu was arrested on the same day the detention order was passed (corresponding to the second scenario above). This assumption is relevant to Indicators (1) and (3).

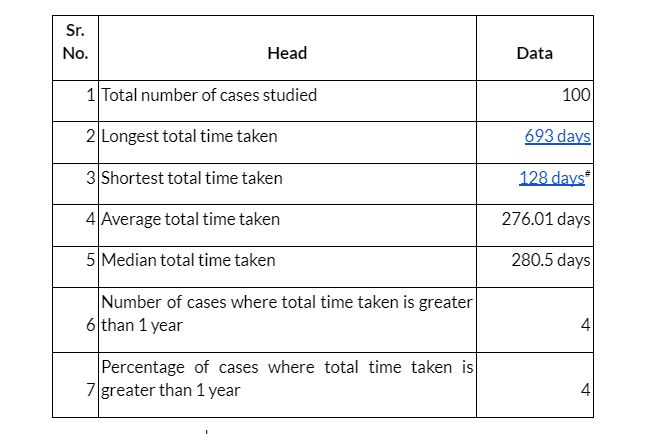

Indicator 1: Time Between Detention Order & High Court Decision

For this indicator, the relevant dates were the date of the detention order and the date of the decision. Both these dates were available from the judgements themselves. We studied 100 cases. The findings are recorded below:

Sources: SCC Online

*This is a reference to the case of Rajesh Singh v. State of U.P., 2010 SCC Online All 560. However, the link redirects only to an interim order in the case; the final order is not available on Indian Kanoon. You can view the judgement here with an SCC Online subscription.

Even though the number of cases in which the days spent between the date of detention order and the final disposal of the habeas corpus petition by the Allahabad High Court exceeds the maximum period of detention under the NSA (i.e. one year) is 4%, the average number of days that are spent between the date of detention order and final disposal is approximately 276 days, 89 short of a year.

However, these delays may not always be entirely because of the Allahabad High Court.

Time could have been lost by the detenu or lawyers through lax behaviour causing delays in the filing or planning processes; and/or the advisory board and/or the government in not promptly confirming or nullifying the detention order when a representation was made by a detenu.

To understand the precise role of the Allahabad High Court in this systemic problem, let us only look at how much time was spent by the Allahabad High Court alone in these cases.

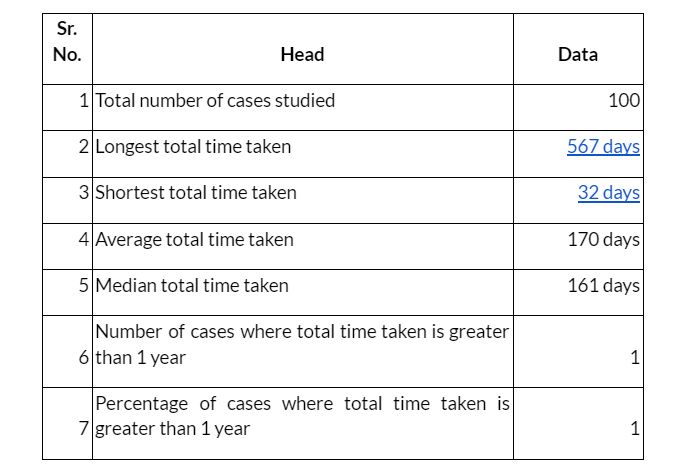

Indicator (2): Time Spent At The High Court Alone

For this indicator, the relevant dates were the date the habeas corpus petition was filed and the date of the decision. We studied 100 cases. The findings:

Sources: SCC Online

This data show that, on average, the Allahabad High Court took 170 days to decide the habeas corpus petition of the detenu. The median figure is 161 days. In only 1% of all cases did the Allahabad High Court take so long in hearing and disposing of the habeas corpus petition that the maximum period of detention under the NSA lapsed.

If we combine the findings of Indicator (1) and (2), the data seems to be pointing towards the lesser role of the Allahabad High Court in the delay in the adjudication of habeas corpus petitions in preventive detention cases.

We can infer that out of the 276 days that pass between the date of the detention order and the date of the final decision, approximately 106 days pass before the Allahabad High Court is moved.

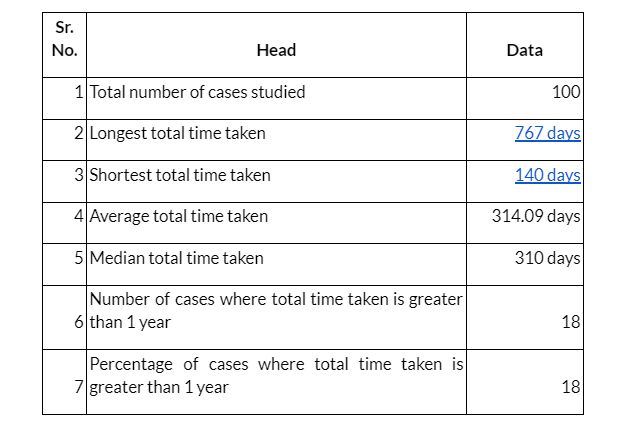

Indicator (3): Time Spent In Detention Until The High Court’s Decision

For the purposes of this study, we subtracted the number of days a detenu was granted bail, wherever a mention of the detenu being granted bail was made. We studied 100 cases. The findings:

Sources: SCC Online

The average time spent by the detenu in actual detention was around 314 days. The median was 310 days, and the maximum period that a detenu spent in custody was 767 days.

In 18% of all cases, the time spent by the detenu in actual detention was greater than one year, the maximum period of detention allowed under the NSA.

All the delay is not attributable to the Allahabad High Court alone. Usually, a part of this delay is not even in connection with detention under the NSA.

This is because, throughout the study, we observed a common pattern: that the police arrested detenus after criminal complaints, offence, or even mere suspicion, and continued to detain them.

When detenus struggled to post bail, a detention order under the NSA was passed, prolonging detention another year.

Much of the time is not only lost between the passing of the detention order and the moving of the High Court, as seen in the discussion under Indicator (2), but also before the passing of the detention order itself.

What The Allahabad High Court Can Do

To reiterate and paraphrase what Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj says about the Supreme Court, there is no good reason why the Allahabad High Court should not consider the period of preventive detention that detenus have already experienced.

The fact that a detenu has already spent a considerable amount of time in custody should prompt the Court to speed up the adjudicatory process.

As we said, where judgements did not mention the date of arrest, we have assumed that the detenu was arrested on the same day the detention order was passed.

We speculate that if the date of arrest of those cases were also to be taken into account, the average number of days spent in actual custody would increase substantially.

'Successful' Habeas Corpus Petitions

By ‘successful’ cases, we mean those cases where the Allahabad High Court quashed the detention order and set detenus free, as opposed to those cases where the Allahabad High Court dismissed the habeas corpus petition and refused to interfere with the detention order.

We studied 73 such cases using three indicators similar to those we used for the complete dataset.

The findings:

Sources: SCC Online

*This is a reference to the case of Rajesh Singh v. State of U.P., 2010 SCC Online All 560. However, the link redirects only to an interim order in the case; the final order is not available on Indian Kanoon. You can view the judgement here with an SCC Online subscription.

Source: SCC Online

Sources for all tables: SCC Online

The findings of the three analyses against ‘successful’ cases can therefore be summarised as:

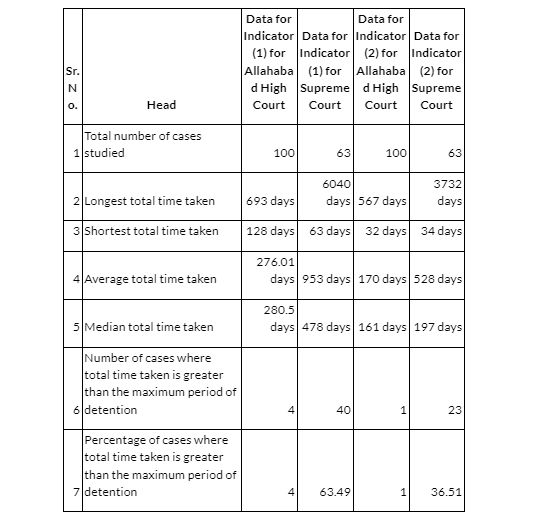

Allahabad High Court Vs Supreme Court

We compared our findings with the 2020 Supreme Court study of NSA detentions by Bhardwaj and found that India’s highest court took 953 days to dispose of such cases compared to 276 days by the Allahabad High Court, exceeding the maximum period of detention by 588 days.

For this purpose, we took indicators (1) & (2) as points of reference, in a similar fashion to Bhardwaj. Indicator (3) has not been taken as a point of reference since there were minor differences in the way Bhardwaj used indicator (3).

Bhardwaj’s study, as we said, covered reported judgements of the Supreme Court between 2000 and 2019, while we covered reported judgements of the Allahabad High Court between 2010 and 2019.

Sources: SCC Online & NUJS Law Review

The average time spent at the Allahabad High Court for adjudication was 170 days; for the Supreme Court, 528 days, which exceeds the maximum period of detention.

The median data of both Courts are closer to each other than the average data. Where the median time spent between the passing of the detention order and its final disposal by the Allahabad High Court was 281 days, the number for the Supreme Court was 478 days. Where the median time spent at the Allahabad High Court for adjudication was 161 days, it was 197 days in the Supreme Court.

While the Allahabad High Court appears to perform better than the Supreme Court in the adjudication of habeas corpus cases, it is clear there are systemic problems with the Allahabad High Court, as our study shows.

(Taha Bin Tasneem is a final year law student at the Faculty of Law, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. Afif Khan is a Capital Markets Associate at IndusLaw, Delhi. Kaif Siddiqui is a PhD candidate at The National Academy of Legal Studies and Research.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.