Updated: Jan 27

New Delhi: The Indian government delayed action on warnings from its scientists to begin preparation for a coming Covid-19 pandemic, according to an Article14 review of records of presentations and an internal meeting.

“Everything is fine as long as you take action,” Naveet Wig, head of the department of medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences told other members of the government’s task force of public health experts on Covid-19 on 29 March 2020. “This discussion has gone on for too long and no action has been taken. No. No. We will have to tell the truth.”

“If we are not able to tell the people of Mumbai, Pune, Delhi or Bangalore public (sic) what is happening in their own cities, how are you going to tell the entire 700 districts?” another task force member said in the same meeting.

Four days after Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered a nationwide lockdown on 24 March 2020, his government’s task force of public-health experts met at the All Indian Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi.

The meeting included Raman Gangakhedkar, head of the Epidemiology and Communicable Diseases Division of the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), the government’s top scientific agency tasked with addressing the pandemic and other top government medical experts.

Our review of the records of that meeting reveal how, having imposed an unplanned lockdown, the government was not prepared even with testing protocols to track down those infected with the Coronavirus, which causes Covid-19. Confusion apparently prevailed, and experts expressed their frustration at the lack of action, despite prior advice.

The records also show, while imposing the lockdown, the government had ignored recommendations from its top scientists. Instead of the current coercive lockdown, these scientists had advised “community and civil-society led self-quarantine and self-monitoring,” through their research in February 2020.

The research had warned of a large outbreak of the Coronavirus in India and indicated that the measures taken by the government until then were not enough. The scientists recommended ramping up testing and quarantining facilities, putting in place nationwide monitoring mechanisms and arranging enough protective resources for health-care workers.

Among the scientists who conducted this research were several later appointed to the government’s task force on Covid-19.

For more than a month, the research and advice of these scientists went unheeded. With no scientific strategy in place, an unprepared government, imposed—with a four-hour notice—a country-wide lockdown, which sparked a livelihoods and food crisis among the poor and migrants.

In the first week of April, as the first part of this series revealed, the government’s top advisor on health, Niti Aayog (the government’s main think tank) Member Vinod K Paul said the best use of lockdown was to buy time to prepare for a scientific plan.

That plan included mass quarantines for congested areas; home supplies to the poor; fast reporting to find infective clusters; measuring the spread of Covid-19 in each district; and increasing intensive-care units and hospital beds for peak-infection periods. Paul indicated that the government required another week to prepare for the action plan.

Records reveal the action plan suggested by Paul was not new but was based on the research finalised by government scientists in February. The scientists had predicted that quarantine for one in every two persons with symptoms of Covid-19 within 48 hours of detection would reduce the spread of the pandemic by 62%. It would, they argued, reduce the number of cases India would have to deal with at the peak of the pandemic.

The government took over a month to even partially consider the advice of its own scientists.

Article14 sent detailed queries to the health ministry and the ICMR and followed up with reminders and messages. Neither responded. This story will be updated if and when they do.

Here is how the sequence of events unfolded.

February: The Research And The Warnings

By January—after the World Health Organisation (WHO) alerted the world and before India found its first case on 30 January—some ICMR scientists, collaborating with colleagues in other organisations, began assessing a possible Indian response to the pandemic.

By the last week of February, they finalised two papers, one a review and another the result of a modelling exercise, were published in the Indian Journal of Medical Research, chaired by ICMR’s Director-General Balram Bhargava. Both papers were available to the government.

The first paper, “The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A review of the current evidence”, was co-authored by Pranab Chatterjee, Anup Agarwal and Swarup Sarkar of the government’s Department of Health Research; Nazia Nagi of Maulana Azad Medical College; Bhabatosh Das of the Translational Health Science & Technology Institute; Sayantan Banerjee of the WHO; and Nivedita Gupta and Raman R. Gangakhedkar of the ICMR.

Warning against a China-like lockdown in India, the paper said: “Instead of coercive top-down quarantine approaches, which are driven by the authorities, community and civil-society led self-quarantine and self-monitoring could emerge as more sustainable and implementable strategies in a protracted pandemic like COVID-19.”

The second paper, “Prudent public health intervention strategies to control the coronavirus disease 2019 transmission in India: A mathematical model-based approach”, was co-authored by Sandip Mandal, Anup Agarwal, Amartya Chowdhury and Swarup Sarkar of the Department of Health Research; Tarun Bhatnagar, Manoj Murhekar and Raman R. Gangakhedkar of the ICMR; and Nimalan Arinaminpathy of the Imperial College, London.

The second paper mapped the possible spread of the infection in India’s four mega-cities: Delhi, Calcutta, Mumbai and Bengaluru. Without any pre-emptive action, the paper’s “optimistic-case scenario” predicted that Delhi alone would see 1.5 million with Covid-19 symptoms at peak. The scientists said if one in every two who tested Covid-19 positive were to be quarantined within three days of developing symptoms, the “cumulative incidence” could come down by 62%.

The ICMR scientists involved with one or both papers—Sarkar, Gangakhedkar Gupta, Murhekar and Bhatnagar—are part of the 21-member national task force on Covid-19. Sarkar is ICMR’s Chairman, while Gangakhedkar is member secretary of the national task force and one of the government’s leading scientific advisors. He appears at daily media briefings in New Delhi on the progress of the pandemic.

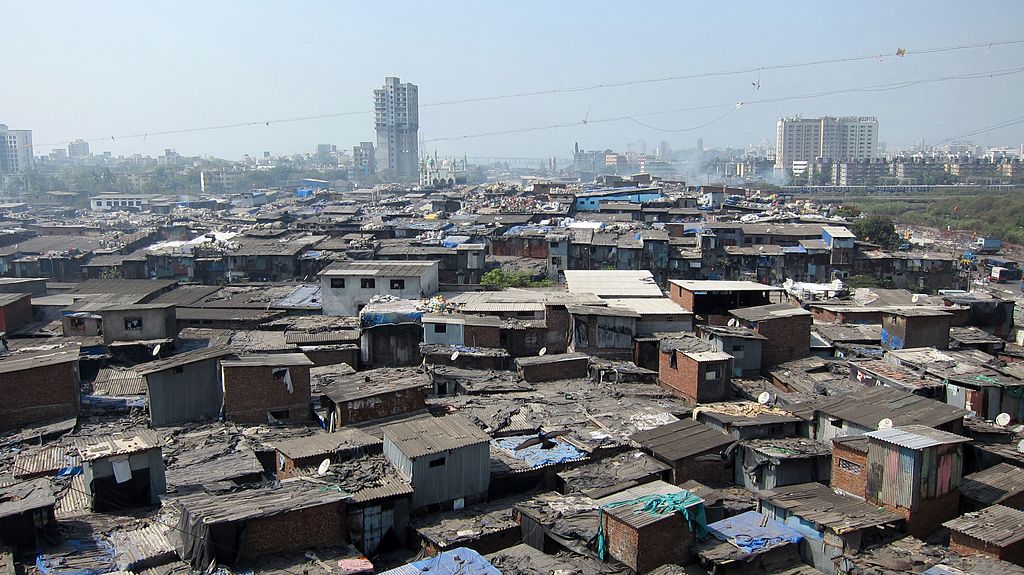

One of the authors of the studies cited above told Article14, on condition of anonymity, that a nationwide lockdown was not the same as quarantine or social isolation. “In Indian conditions such a lockdown provides social isolation for only the rich who live in less dense and high-floor space areas,” he said. “To some degree it can protect them from the spread.”

“But, for the poor, without high levels of door-to-door screening and the fastest possible quarantining of those found positive, a lockdown will only help the virus spread intra-community,” said the scientist. “The poor in dense urban areas share very small physical spaces, (they) live with common facilities, such as public toilets. The lockdown has forced likely COVID-19 patients to share these spaces for weeks with others. Imagine if one COVID positive person is sharing a community toilet with hundreds, if not thousands, daily, spreading the virus and the coercive lockdown is only restraining him (sic) from going to authorities.”

The government did not take account of these research findings in February.

March: Task Force And The Lockdown

On 18 March, the government constituted the Covid-19 task force of 21 scientists and public health experts headed by NITI Aayog member Paul.

While the task force deliberated, on March 24, the Prime Minister ordered the 21-day nationwide lockdown.

Four days later, the task force met once again.

This is when Wig, the AIIMS head of medicine expressed his dissatisfaction at the lack of science-based action to contain Covid-19. “What I am saying is what has been the task force’s response to the pandemic?” asked Wig. “I don’t know... what have we delivered? What has this task force delivered? We have to think. So tell us, what we have (sic) delivered?”

Gangakhedar, the ICMR head of the epidemiology and communicable diseases and the member secretary of the task force responded: “That is a good question. Don’t ask me. I am not the chair [The task force is headed by the NITI Aayog Member Paul and co-chaired by Union Health Secretary Preeti Sudan and the ICMR Director-General Bhargava, but none of the three chairs attended the meeting]. Even I have been questioning.”

One epidemiologist at the meeting said: “The problem is right now people are not coming to the hospitals because of the lockdown. We are doing all the SARI [severe acute respiratory illness] surveillance, we are doing all that, but we have very limited numbers coming to the hospitals. So the thing is you will have to go to the households. And how that needs to be done, whether IDSP [Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme] will do it or the district administration will do it, that is the only thing that needs to be sorted.”

Their comments implied that until the end of March, the government was still not doing enough surveillance to find those with Covid-19 symptoms, and the lockdown had hampered rather than helped. Neither was it clear how surveillance should be expanded.

There were other experts at the meeting who agreed and said detection had become a problem because people showing symptoms of influenza-like infections would just not come to the hospitals during the lockdown.

A senior ICMR epidemiologist told Article14, on condition of anonymity, that discussions were yet to be held “to figure out what is the testing strategy”. He said a countrywide scientific testing strategy would be decided through meetings in ICMR over the “coming days”.

A long discussion ensued on setting in place the “case definition”, which is a set of uniform criteria used to define and surveil for a disease, a precursor to mass surveillance. The discussions also centred on who should do this surveillance, which would require going home to home and not waiting for those with symptoms to come to hospitals during a lockdown.

One committee member said during the meeting: “Since lockdown (sic) we are only saying that, okay, people will not go to the health facilities, but we have to also take into view what the ministry is planning and doing... and many states have already initiated app-based self reporting.”

Gangakedhkar said at the meeting that testing protocols were not in place, so far, and he would discuss this issue with the ICMR director general and other researchers.

April: Paul Revives The February Research

In the first week of April, Niti Aayog member Paul suggested to the government that it begin what he termed a “continuum of care”, a reference to the recommendations the government scientists, including ICMR’s Gangakhedkar, had made through the two research papers previously cited.

Paul advised community-based surveillance and testing, as did the scientists, who urged urgent quarantines of those with symptoms in India rather than a lockdown.

Paul did not say the lockdown should be withdrawn. He did say that the ICMR had noted its shortcomings and recommended that the government use the lockdown to buy time and plan for door-to-door nationwide surveillance.

This rapid increase in surveillance and testing, he said, would allow people with symptoms to be placed in government-provided quarantines; those who could afford to, could be self-quarantined.

On 6 April, the task force constituted research groups to identify priorities and begin studies, including those for increased surveillance. On 14 April, still unprepared for door-to-door surveillance and gradually ramping up the rate of testing, which is one of the world’s lowest, the government extended the lockdown to 3 May.

Series concluded. You can read the first part here.

This reportage was supported by the Thakur Family Foundation. The Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this reportage

(Nitin Sethi and Kumar Sambhav Srivastava are independent journalists and members of The Reporters’ Collective.)