Mumbai: “Sushant Singh Rajput was killed after he busted a gang of Bollywood insiders who trafficked children, tortured and killed them to extract ‘Andrenochrome’ from their tears. The chemical made the stars look young.”

“Rajput ran an NGO rescuing young girls. A senior actor tried to rape one of these girls. Rajput decided to expose the actor and hence, the actor killed Rajput and his manager, Disha Salian.”

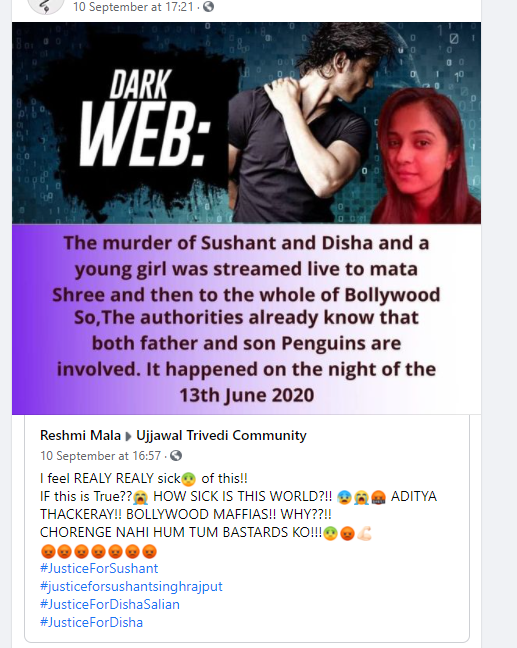

“Rajput and Salian’s murder was streamed live to Matoshree [the Thackeray residence], Dawood and whole of Bollywood on Dark web.”

Over three months after actor Sushant Singh Rajput’s death by suicide—confirmed by a 7-member panel of doctors at New Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) on 2 October—conspiracy theories run riot across Facebook’s groups and pages dedicated to seeking ‘justice’ for the late Bihari actor. Followed by hundreds of thousands of accounts, the users of these pages and groups give life such outlandish theories.

The theories have a common strand—they target the Shiv Sena and its leaders, Maharashtra chief minister Uddhav Thackeray, and his son, minister Aaditya Thackeray, celebs who are deemed to be anti-government and the Mumbai police.

Many theories hold the Thackerays responsible for Rajput’s “murder,” with one popular string alleging that Aaditya wanted to “steal” Rajput’s invention, an app that detects coronavirus in patients through their voice.

Much of the online onslaught has been planned with political gain in mind, according to a research paper published on 24 September. The researchers noted how conspiracy theories were accompanied by a “systematic targeting” of the Shiv Sena-led government in Maharashtra, with accounts linked to Sena’s ally-turned-foe, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), “the most active in attacking the city police of Mumbai,” the paper found.

On 5 October, the Mumbai Police announced they had found over 80,000 fake social media accounts that were created on 14 June, the day Rajput died, and had been used to “target the Mumbai Police with abusive tones”, Police chief Parambir Singh was quoted as saying in the Hindustan Times.

From accusing actor Salman Khan of harvesting children’s organs to extract a chemical that makes him look young (see below) to alleging that Rajput’s murder was telecast live on the dark web (see below) and viewed by fugitive terrorist Dawood Ibrahim, users on these groups and pages exchange these theories without sharing any evidence backing their claims.

These theories are then weaponised—lists are made of personalities whose involvement is suspected and an organised campaign is mounted to show them their “aukaat” (worth), as users repeatedly post.

From drafting mass emails and sharing email addresses of top corporate honchos asking them to remove these actors from corporate endorsements to circulating old, often misleading videos, and heaping allegations of drug abuse and even, murder, on these celebrities, these groups often encourage followers to do the same.

The same treatment is meted out to those who publicly question such claims or back Rajput’s partner, Rhea Chakraborty, as misinformation, peppered with abuse and slander, proliferates unchecked.

Facebook’s Community Standards on bullying and harassment warn users against posting such content and specifically, warns against posting content with “female-gendered cursing terms when used in a derogatory manner”.

Despite posts attacking various female celebrities, from Chakraborty (see below) to actor and Member of Parliament Jaya Bachchan, there appeared to be little intervention from Facebook.

Pointing to the targeted attacks on other celebrities, the research paper said: “It may be far from coincidental that a lot of the celebrities being trolled in the aftermath of the suicide were among those who were critical of the government in the past.”

Article 14 sought comment from the admins of three pages—Justice for Sushant, Justice for Sushant Singh Rajput and We Fight Together for Sushant—but they did not respond to messages.

We also sought comments from Facebook, sending emails and messages over five days, but the company did not respond. On Facebook’s request, Article 14 even sent the social media company detailed evidence in the form of screenshots and links to misinformation inside these groups. If Facebook responds, we will update this story.

A Parallel Investigation

The insinuations on these groups are increasingly in danger of spilling out of the digital world and into the real world, said experts.

After theories that Rajput’s autopsy was “not conducted” in order to allow his “killers” to go scot-free, doctors at Mumbai’s government-run Cooper Hospital, who conducted the autopsy, were reportedly harassed and abused after their contact details were shared online.

Bachchan, who criticised allegations of widespread drug abuse in the Hindi film industry, was trolled so relentlessly on social media platforms, that the Mumbai Police increased her security.

In 2016, a conspiracy theory known as ‘Pizza Gate’ spread rapidly across the Internet in the US. It alleged that senior Democratic Party officials were involved in a child-sex ring led run from popular pizza restaurants by then presidential nominee Hillary Clinton. So convincing were these theories that a man, wanting to free these children entered one of these pizzerias and fired from an assault rifle he was carrying.

At the core of Pizza Gate lay the fact that the conspiracy theory was so compelling that people felt the need to conduct their own investigation— 28-year-old Edgar Welch, arrested for firing his rifle inside the pizzeria in Connecticut in December 2016, later told the police he wanted to “self-investigate” the allegations.

A striking parallel exists with posts on these Facebook pages and groups—a need to crowd-fund investigations into the late actor’s death (see below).

For instance, a Facebook user from Kolkata, Twisha Ray, who is part of ‘Justice for Sushant Singh Rajput,’ (see below) one such group with nearly 770,000 followers, told Article 14 that she believed his death was “not normal.”

“He was fine, he healed introverts and many people. I feel, the person who commits suicide [sic] is cowardly and stupid,” Ray said, adding that this was why Rajput could not have died by suicide.

Ray believed that the probe agencies were not doing their job well. On 17 August, she posted on the group that Rajput’s muder was “clearly a planned murder.”

Sharing photographs of Rajput’s body, with a red-circle around a black spot on his neck, Ray said this indicated that “they (murderers) used a stun gun to paralysed him first (sic).” She said the murderers deserve nothing more than being “hanged for killing a beautiful soul so mercilessly”.

Such posts are common.

A video posted in a group called ‘Justice for Sushant’ with over 101,000 followers, on 30 August with the title “The complete truth of what happened with Sushant Singh Rajput on 14 June” has a similar theory.

The video has visuals of Rajput’s body on the bed with police officers standing around him. The video deconstructs the crime scene, alleging how Mumbai police officers were tampering with evidence. The video even alleges that Rajput was alive when the video was taken but that the Mumbai police covered his body with a white sheet to hide this.

Another video, in the same group, on 24 August, alleged that Rajput’s body had “many injuries” suggesting that he was assaulted before being murdered. The video zooms into his body and alleges that there were bloodstains on him, but the visuals are hazy and grainy. The video got 9,300 likes and had more than 850 comments. One person, commenting on the video said, “I can’t tolerate any more. Pls hang all the culprits.”

The same day, another video in the group alleged that the pillow in Rajput’s room, shown lying at his feet, had a shoe mark, which indicated Rajput was suffocated with the pillow. “Then the murderer stood on the pillow. Such a shoe mark can only be of someone who is 90-100 kg and could be a bodyguard to someone,” said an unspecified woman’s voiceover on the video, adding that she suspects the involvement of Shera, Salman Khan’s bodyguard. The video had over 10,000 likes.

At the centre of the insinuations around his death is Chakraborty. Almost all the groups researched for this article have posts dedicated to how Chakraborty is the lynch pin, at best, or a willing pawn, at worst, in Rajput’s death. Many posts express hate and anger towards Chakraborty, hurling misogynistic slurs and abuses at her.

One Facebook user, Sonali Mitra, part of the “Justice for Sushant Singh Rajput” group, wrote on 3 August that Chakraborty was a “plant” by “Salman’s gang” and “had a clear agenda from day 1, which was to destroy Sushant in every way”.

Mitra, in her post, said Chakraborty was “caught at all elite parties, trying to use her manipulative ways to get films”. In another post on 14 September, Mitra calls Rhea “a lying witch” and a “seasoned criminal”.

Mitra told Article 14 that her posts were based on her beliefs, “established through multiple news and agencies I myself research upon and various lawyers, activists, family and friends of SSR that is available all over media (sic)”.

“Through few theories (sic) I have put across may not be cent percent accurate and subject to more investigation, there is no doubt that the bigger picture is totally shrouded,” said Mitra.

On 10 September, a day after Chakraborty was arrested by the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) on charges of procuring drugs for Rajput, Ray said that there was “proof” that Chakraborty was “wearing ear buds of skin colour so no one can notice and she can leak all the information to her advocate Satish Maneshinde or to her boss”.

One popular video, liked by 34,000 people, with 3,000 comments, is a self-recorded video of an unknown, masked woman. The three-minute video starts with the woman abusing Chakraborty: “The whole world wishes ill on you. Even in hell, you will suffer. Even capital punishment will not suffice for you.”

The woman goes on to allege that Chakraborty used to slip drugs into Rajput’s drinks. “Why did you hate him so much, Rhea?” she asked. “You were, anyway, usurping his money and using it for shopping.”

Virtual Lynch Mobs

Such antagonism towards Chakraborty—one post calling her a “sexually-corrupted murderer” has over 2,400 likes—is also extended to anyone else who is seen backing her or questioning these conspiracy theories.

The day after the AIIMS panel ruled that Rajput had died by suicide, these groups and pages were abuzz with posts demanding the arrest of Dr Sushil Gupta, who headed the 7-doctor panel, alleging that he could be “bribed easily” and that he had a “history in misleading investigation and giving false report (sic)”.

Television news channels who don’t toe the line are made the subject of organised boycotts and systematic protest campaigns.

For instance, on 27 August, hours before Aaj Tak telecast an interview it conducted with Chakraborty--her first since Rajput’s death--‘Justice for Sushant Singh Rajput’ group administrator, Elisha Sigera, asked (see below) the 770,000 members of the group to unsubscribe to the channel’s YouTube page because, she alleged, the channel was trying to “create a narrative in favour of the prime accused, while the investigation is on”.

On the same day, Sigera asked followers to tweet using the hashtag “#ShameOnAajTak”, tagging the Twitter accounts of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Home Minister Amit Shah among others.

Similar campaigns and boycott calls have gone out against other actors.

For instance, after Bachchan made her speech in Parliament, users started posting messages promoting a boycott of her family’s films and products they endorse. Users on these pages have unleashed a tirade of memes, videos and photos targeting the family and alleging that they are drug addicts.

There are videos of Bachchan’s daughter, Shweta Bachchan Nanda, walking out of what looks like a club with captions suggesting it was “proof” that she was consuming drugs. One user, commenting on such a post, said, “Let’s bring down this family and the industry.”

Other stars have also been targeted similarly, because of their silence on the issue and refusal to back such conspiracies.

These groups, for instance, target actor Shah Rukh Khan and allege that he has links to people connected with terrorist organisations. One post, by user Dedur Paul (see below), alleges that using products endorsed by Shah Rukh would, indirectly, benefit terrorist organisations and hence, advocates a boycott of the products he endorses. Paul, when contacted, declined to respond to questions about his posts.

Mumbai-based sociologist and professor Nandini Sardesai, said that such “virtual lynching” can be cathartic for many who have started “identifying” with the case.

“In the times of this pandemic, people have not been able to find a vent to their anger and frustration,” said Sardesai. “So, many find this virtual lynching of people and targeting them to be a catharsis of some sort.”

The 75-year-old sociologist said that the mass frenzy around Rajput’s death, from public interest in the case to the flood of conspiracy theories, is closely linked to the pandemic.

“There is a certain vacuum, because people are not leading a normal life. What was always normal is not normal any more. So, there is a sense of normless-ness right now,” she said.

Amidst the pandemic-driven gloom and despair, the frenzy around Rajput’s death is a “stimuli” for many.

“People are craving for some sort of stimuli in their lives,” said Sardesai. “Since we have been denied most pleasures of our old life, becoming part of the social media frenzy around this episode becomes the only vicarious experience that gives people pleasure.”

Facebook’s Selective Action

There is also another kind of vacuum at work here, according to Prateek Waghre, a research analyst probing information disorders at the Takshashila Institution, a think tank.

Waghre said that Rajput’s suicide also created an information vacuum.

“When people do not have a lot of information about something, they will look at anything that can calm their anxiety,” said Waghre. “Similarly, when there is only a little information about something, that creates an information void and people look to fill the void up with their own conspiracies.”

He cited the investigation into Rajput’s death as an example of such a void, fuelling a new genre of misinformation in India. “The investigation will take time to reveal more details but till then, people will come up with their theories,” he said. “This is very unique, since we have never before seen so many conspiracy theories being exchanged on social media about a single incident.”

But these conspiracy theories did not exist in isolation. In their paper, researchers concluded that these theories were accompanied by other narratives that were being deliberately peddled-- “the local police was proposed as incompetent or in cahoots with the cabal, the state government itself was presented as nepotistic and inimical to the interests of poor outsiders,” the paper found.

What helped spread these theories was an active push by news channels who “drove the the idea of murder,” according to the paper. Joyojeet Pal, a researcher on social media and society and one of the researchers, told Article 14 that this was symptomatic of a larger trend.

“The problem with the disinformation is partly that so many mainstream media channels indulge in variants of it—from clickbait journalism and biased information to outright lies that slowly people stop differentiating between stuff on WhatsApp and stuff on the news,” said Pal.

Waghre said that there were “striking and disturbing parallels” between the wild swirl of conspiracies around Rajput’s death and the rise of QAnon, a far-right conspiracy theory, prevalent online in many western nations, especially in the United States, that believes there to be a wide-spread paedophilic ring among elites in the establishment that US President Donald Trump is secretly fighting. Its followers have been linked to violent incidents over the last one year, including a purported attempt on the life of US Presidential nominee Joe Biden.

On 19 August, Facebook announced it was taking down 790 groups, 100 pages and 1,500 ads on Facebook linked to QAnon and had blocked over 300 hashtags on Facebook and Instagram. A Twitter thread by a BBC journalist, analysing this action, showed that the total members part of this group were nearly 600,000.

In India, despite the conspiracy theories around Rajput swirling for over three months now, Facebook has so far failed to take action. In all the groups, analysing hundreds of posts, Article14 came across only one instance of Facebook notifying a post that claimed that Chakraborty was slapped by CBI officials during her interrogation to be tagged “False Information.” Even then, the post was fully visible to users.

Waghre said Facebook’s refusal to act was not surprising. “There is a stark contrast between what is happening in the US and India, where we have seen social media platforms employing different rules to regular similar events in both countries.”

According to Facebook’s Community Standards, it does not “remove false news from Facebook, but instead significantly reduce its distribution by showing it lower in the News Feed”.

This unheeded flow of misinformation might already have consequences.

Many users across these Facebook groups and pages had, without evidence to back it, claimed (see below) that Rajput had developed a new game, ‘Fau-G’ launched a day after the government banned the popular online game ‘Players Unknown’s Battle Ground (PUBG).’

In a post on 5 September, the admin for ‘Justice for Sushant,’ a page with over 101,000 followers, uploaded a video insinuating that actor Akshay Kumar had “stolen” the game from Rajput. The video got nearly 9,000 likes, with over 4,400 people sharing it and 1,600 comments.

So persistent were these rumours that the makers of the game, GOQii Technologies Private Limited and Sudio nCore Private Limited, approached the Bombay City Civil Court, asking it to restrain social-media users. Despite a Court order on 18 September, Article 14 found such posts continued to exist.

Waghre warned that the long-term effects of such a discourse are dangerous. “The discourse is getting uglier and uglier,” he said. “Someone might decide to take matters into their own hands.”

(Kunal Purohit is an independent journalist based out of Mumbai. He tracks the intersections between development, politics, social justice and technology.)