Mathura, Uttar Pradesh: On 9 August and 14 August, officers of the Agra division of the North Central Railway demolished 135 houses in Mathura town’s Nai Basti, a cluster of brick and cement homes 250 m behind the Krishna Janmasthan temple complex, a group of Hindu temples that bring this town in western Uttar Pradesh (UP) several million tourists a year.

Muslim and Hindu homes shared boundary walls in a few places in Nai Basti, but Hindu houses remained untouched, said residents. Some said they had lived in these houses for more than seven decades; the houses themselves were 50 to 60 years old, standing on land being cleared by the railway for a project to connect the town with the nearby temple town of Vrindavan, lying 14 km north.

Kadir Khan, 50, sat under a tree near a heap of rubble that used to be his home in Nai Basti. “We have understood that this is a measure to remove us from here,” he told Article 14. “They do not want Muslims here.” He said the Hindu houses behind his house had not been touched.

His demolished home used to share a boundary wall with a row of homes that were still standing, he said, all belonging to Hindus.

Khan, who ran a small bakery shop next to his house, is now without livelihood.

Kunwar Narendra Singh of the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), an opposition party in UP, told Article 14 that the North Central Railway had avoided clearing land where the Hindu community lived.

“From the centre of the railway track, 36 feet were to be taken from either side, but they took 56 feet from one side,” said Singh. Houses of Hindu baniya caste traders, standing 12 feet to 15 feet from the track on the other side, were spared, he alleged

“If they are doing this by targeting only Muslims, then it is wrong,” said Singh.

More than 60,000 homes of mostly low-income families were demolished across India by the union and state governments between January 2021 and March 2022, a new report by advocacy and research group Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) has revealed.

The HLRN report said State authorities had evicted over 1 million people in the last five years. In the national capital New Delhi, demolitions were carried out in various localities ahead of the G20 summit, which wrapped up on 10 September.

India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has increasingly used bulldozers to demolish Muslim-owned properties on charges that their occupants were “illegal encroachers” or alleged rioters, the latters’ families forced to face a form of collective punishment, said experts.

In many instances, legal processes mandating serving of notices and assessment of whether relocation is possible were bypassed. Legal experts have deemed several instances of demolitions as unconstitutional and illegal.

In the case of the Mathura demolitions, too, experts said due process had been abandoned.

“It is very clearly written that if someone is in the settled position, meaning someone has been living at a land for a long time, and even if they are not the owners, even then you need to follow the process of law,” said Supreme Court advocate Sanjay Parikh.

If the people are to be removed from the land, “a proper rehabilitation process” should have been followed, said Parikh.

Article 14 tried to reach the district magistrate of Mathura, Shailendra Kumar, who was present during the demolition, but he was not available for comment.

A Temple, A Mosque & Muslim-Owned Homes

The Krishna Janmasthan temple complex comprises three main temples inside the premises—the Keshavdev temple, the Garbh Griha where the god is believed to have been born, and the Bhagvata Bhavan where Krishna and his consort Radha are presiding deities. The complex shares a wall with a 17th-century mosque, with which it has been locked in a legal dispute since 2020.

In September that year, a plea was filed by Lucknow resident and advocate Ranjana Agnihotri and six others, originally in a lower court, seeking to remove the Shahi Idgah mosque from the temple complex.

The residents of Nai Basti claimed that the demolition was a way to remove Muslims from near the disputed area.

In response to a writ petition filed by a resident in the Supreme Court days after the first round of demolitions in August, the Railways said in an affidavit that the petitioner’s move to challenge the demolition drive gave its action a “communal overtone” by linking it with the disputed religious premises.

The petitioners maintained, however, that the demolition was meant to remove Muslims who have lived here for decades.

“Has any Hindu home been demolished?” Kadir Khan asked. “If it is not communal then what is it?” He said the demolition squad stopped as soon as bulldozers reached the area where Hindu homes were located.

Another resident, Imran Khan, echoed the same sentiments and alleged residents were beaten, all Muslim. “The women were also not spared,” he said.

Kunwar Narendra Singh of the RLD helped the residents of Nai Basti approach the courts and held a rally to support their demand that the state government rehabilitate those made homeless.

Singh said he had accompanied some residents to the offices of the railway officials and to the city magistrate, seeking more time before the demolition, but had not had any success.

He added that his protest was not against the railway project and that “it was about time” that Mathura and Vrindavan were developed as a religious hub.

‘Our Forefathers Lived Here Before Us’

Residents alleged that they found out about the impending demolition from local media reports in February 2023 that the North Central Railway was to start a new project on their land.

Nitin Garg, senior divisional engineer of the North Central Railway’s Agra division, told Article 14 that notices regarding the demolition were served, but did not elaborate.

Some residents confirmed that in June 2023, officials and policemen arrived to mark the homes slated for demolition, and at the time also pasted notices on the doors of these houses.

Kadir Khan, whose house was demolished, said his house was marked ‘R-18’.

However, no immediate action followed. A civil suit regarding the North Central Railway’s claim over the land had been filed as far back as 2005, and the civil court had not passed an order on the residents’ legal status.

According to residents, they went about their lives as usual until the morning of 9 August, when police and railway officials entered the colony with bulldozers.

According to residents, people began to run around trying to retrieve belongings. In the chaos, Imran Khan, 24, who was inside a washroom, unaware that their homes were being razed, suddenly found bricks falling on him. He sustained an injury on his hand, which required stitches.

Speaking to Article 14, the e-rickshaw driver said his family had lived in Nai Basti for as long as he could remember. “Our forefathers lived here before us,” he said. “Suddenly they came and started demolishing our house.”

In a statement issued in August, Prashasti Srivastava, public relations officer for the Agra division of the North Central Railway, said, “Advance notices had been issued to the encroachers living illegally alongside the railway track.”

Two hundred houses received notices, according to the statement, while 135 were demolished on 9 and 14 August.

The structures were removed as part of an effort to convert the existing metre gauge railway track into broad gauge between Mathura and Vrindavan, a distance of 12-km.

Addressing the media in 2022 in Mathura, BJP member of Parliament from Mathura Hema Malini had said this was “a very big project”.

Malini said “minor hurdles” were being ironed out, and that she expected the railway line to eventually go beyond connecting Mathura and Vrindavan, instead reaching the town of Gokul too, 15 km southeast of Mathura. “This is going to be a smaller kind of a metro,” she said.

No School For Children, No Water, No Electricity

In makeshift shelters near their demolished homes, residents said the government had offered neither assistance nor resettlement.

Young boys sat quietly or walked amid the rubble, while girls carried pots of water on their heads and helped with household chores, school forgotten for now. The residents were still baffled by what had happened.

In a tent surrounded by bricks and rubble, 30-year-old Afsana Fatima tried to soothe her one-year-old son on a scorching September midday. “Our children are suffering. We have no water or electricity,” she told Article 14. Two of her older children stood nearby. Fatima’s husband, who drives an e-rickshaw, had to skip work since the demolition, and fretted about how to feed five children.

“We don’t have money to rent a place and are forced to live in this makeshift tent here itself,” Fatima said. Her home was a shanty, but others had lost brick homes with an upper floor or two.

As temperature rose in the weeks after the demolition, residents remained under the meagre shade of the tents, with nowhere else to go.

Fatima’s youngest son’s forehead was covered in a rash, which a doctor told her was on account of the heat and inadequate water. Homeless and without any earnings, she said the family had been visiting government hospitals for check-ups and to buy medicines.

Like Fatima, most of the suddenly homeless residents of Nai Basti were day wage workers, earning their livelihood by selling fruits and vegetables or metals or by driving e-rickshaws.

Imran Khan has not been able to go to work due to his injury, which required medical care and several thousands in medical bills.

A father of two, Khan’s children have also not been able to attend school since the demolition. Most children in Nai Basti have had to skip school, residents said.

“Most of the people are still staying here and as you can see there is no water and electricity,” asked Imran Khan. “How will children go to school in such a condition?”

The demolitions were first carried out on 9 August. Residents alleged they were not even given time to move their things out, and that their household belongings were crushed by the bulldozers even as they pleaded with the administration to give them time.

“They came without any notice,” 75-year-old Amina told Article 14. “I was pushed away when I requested a policewoman to give me some time,”

Seated under a tent on a cot, the only furniture she had been able to salvage, Amina said she was angry with the administration and the media. “What will you people do? It has been more than a month and we don’t even have water or electricity,” she said. “No one is coming to help us.”

A widow, Amina’s children work outside Mathura and she had nowhere to go. Nai Basti was the only home she knew, she said.

As residents continued to live amid the rubble, stagnant water began to collect in the middle of the colony, formerly a pathway but now covered by rubble. Residents said the situation was not sanitary.

“Children are more exposed to diseases,” said Fatima. “The water is so dirty and it might lead to health hazards, but what can we do except continue living here.”

SC Sends Petitioners Back To Civil Court In Mathura

On 14 August, the demolition squad returned, following which a resident named Yakub Shah approached the Supreme Court. On 16 August, the apex court halted the demolition for 10 days. However, on 28 August, the court asked the petitioner to seek relief before a civil court, noting that suits instituted by residents of the land were pending before a local court.

The bench refused to extend the status quo granted on 16 August.

Shah’s lawyer Radha Tarkar who was present at the Supreme Court hearing, said the residents had been living in the colony since the railway tracks were first built.

While residents have documents including electricity and water bills dating back 50 to 60 years, the petition said people had started to inhabit the land when the metre gauge railway track was laid, in the 1870s.

Residents said they did have proof their ancestors lived here, but Amina who is 75, said she was born here.

Earlier, when Shah along with 15 other residents filed an interim application with the Mathura civil court seeking an urgent hearing the very next day, the court scheduled the matter for 14 August, but could not hear the case on account of a state-wide holiday declared by the bar council of Uttar Pradesh.

Mohammed Iqbal, a local lawyer who also lives in Nai Basti, said the civil court judge had not been present.

The strike by lawyers in Uttar Pradesh, which began after advocates were baton-charged by UP police in Hapur on 29 August, was withdrawn on 15 September.

A Land Claim Made In 1994 Is Still In Dispute

The North Central Railway first staked a claim on the land occupied by Nai Basti in 1994, when residents of the time received an order stating that the land would have to be cleared as it was the property of the railways.

Shah’s petition in the SC makes a mention of this claim.

Tarkar said that residents did not immediately understand the import of the order, which was in English, but that in 2005, they approached the Allahabad high court, which asked them to approach the lower court.

Residents of Nai Basti filed a civil suit in a Mathura court on 15 March 2005, seeking a permanent injunction against the railways.

Among the five petitioners in the 2005 suit was Yakub Shah, who also approached the Supreme Court in August 2023. The 2005 suit was dismissed in 2015 by the Mathura civil court on account of a continuous absence of the petitioner.

In April 2016, residents filed a restoration application, which is currently pending before the Mathura civil court.

“The railways have not been able to prove that the property belongs to them till date,” Tarkar said.

In response to the civil suit filed by the petitioner before the Mathura court in 2005, the railway had merely said the land was its property, without citing any evidence.

The date of hearing of the restoration petition has been forwarded ever since and the matter is still pending in the Mathura civil court.

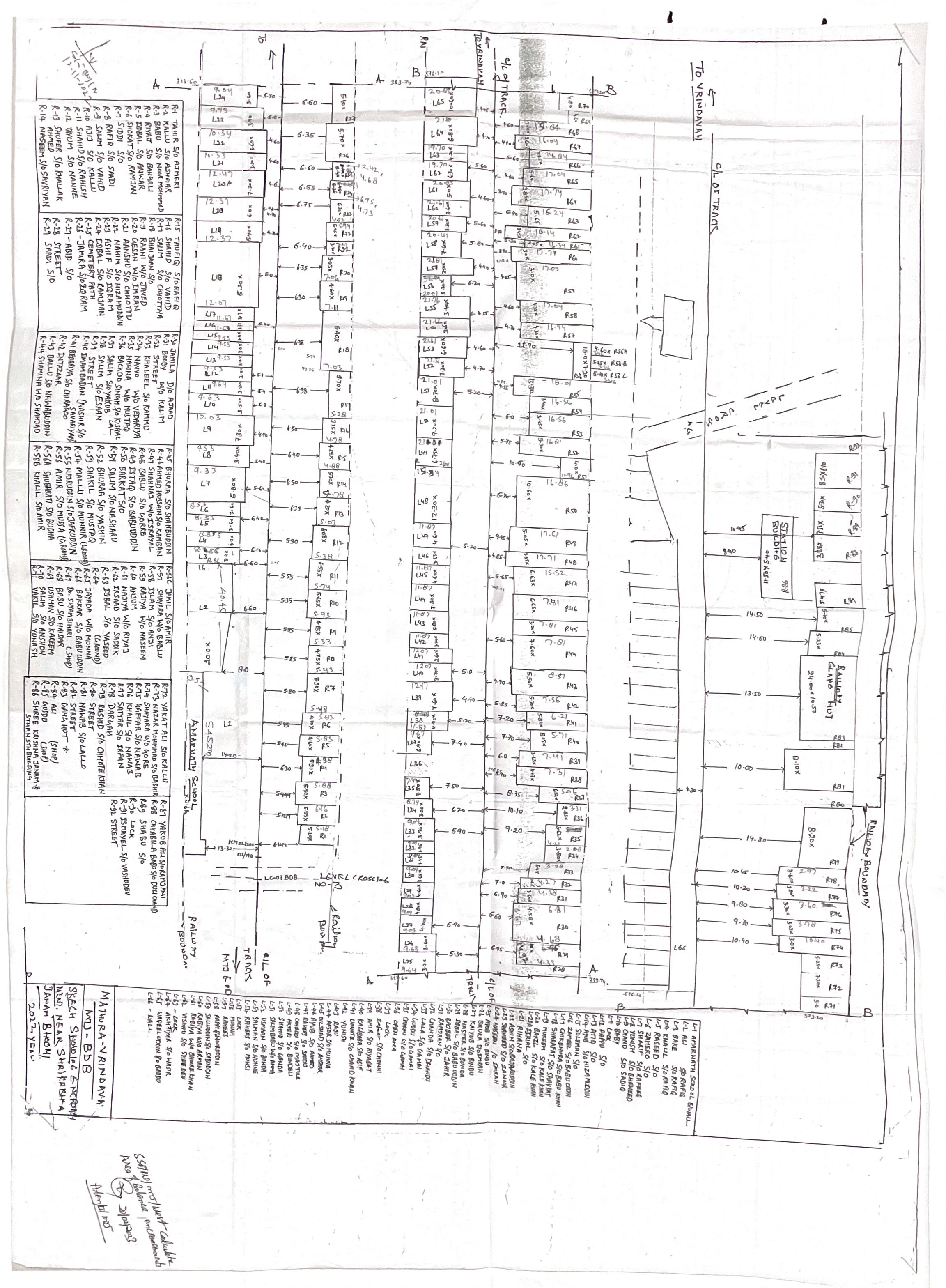

In response to the present petition filed in August, in an affidavit filed in the SC, the North Central Railway included a copy of a hand-drawn railway map showing Yakub Shah’s house as an encroachment. In the same affidavit, however, Nitin Garg, senior divisional engineer of the North Central Railway’s Agra division, claimed that Shah did not have the locus to file a petition for he was “not the subject matter of the eviction drive”, meaning Shah’s property was not one of those demolished.

However, Shah’s house was marked by the staff of the North Central Railway with the words ‘R87’, in sequence with other structures earmarked for demolition.

Tarkar alleged that the North Central Railway was changing its statement to the court—its affidavit in response to the 2005 civil suit said the petitioners (including Shah) were encroachers on land acquired by the railway while its 2023 affidavit said Shah’s property was not being demolished.

Meanwhile, with the restoration application for their civil suit pending in the civil court, the residents had nowhere to go. “We were born here and we will die here,” Amina said.

(Mohd Abuzar Choudhary and Nikita Jain are independent journalists based in New Delhi.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.