Updated: May 1, 2020

New Delhi: With 30,000 known cases of Covid-19 and deaths approaching 1,000, despite a nationwide lockdown of more than a month, correct and adequate data is required for the government to be able to decide the correct course of action with respect to testing, quarantining and to decide how and when restrictions can be lifted.

Evidence-based decision making also helps build public trust, which ensures better compliance with the government’s measures. But to achieve these ends, the Centre and states have resorted to emergency-like powers to collect and share personal information, drones and cell-phone location data to enforce quarantines and published lists with granular details of those under quarantine. While the need for extensive information is undoubtedly important, the means adopted merit closer scrutiny.

The Global Use Of Data To Combat Public-health Crises

Globally, lawmakers recognise that states and healthcare providers may find it difficult to comply with the rigours of data protection, or that the need for data may outweigh privacy concerns in times of public health emergencies.

Data protection and privacy laws, therefore, almost always provide for exceptions to the use of personal information in the interest of public health. However, these are not blanket exemptions; increased surveillance on the ground of securing public health must be necessary to prevent or contain the spread of the disease, and they must be the least restrictive means available to the state.

A necessary corollary to these principles is that such enhanced surveillance must be rolled back when the crisis subsides, with rigorous controls over how the data collected during this time is to be archived or used.

Several governments have ensured that the use of data and broader disease-surveillance activities are compliant with these principles. Examples of such measures can be found in pre-existing plans that some jurisdictions have had in place in anticipation of epidemics. In other cases, such examples are seen in the way privacy laws have been adapted in the face of the current situation.

In South Korea, for instance, the law guiding prevention and control of disease outbreaks was amended after the outbreak of MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) in 2015, to enable government authorities to collect data from a number of sources. The law provides that each person whose data was collected is notified of the collection and processing of data. The data must also be destroyed after it has been processed.

Similarly, in Canada, the government explained in March 2020 how data could be collected and processed legally, using exceptions already available. In the European Union, European Union (EU) and national authorities have done the same, applying public-health exemptions under the EU data-protection law.

These laws and statements emphasise on the right of citizens to know, and the need for government authorities to be transparent in their use of data.

India’s Response: Surveillance Without Safeguards

In India, none of the extreme measures that central and state authorities have used appear to consider personal privacy and the need for safeguards.

For example, reports indicate that immigration data of passengers returning to India was shared with local police authorities and health workers. To enforce quarantines, this data was then publicly shared or shared with private companies to create applications for surveillance.

Both instances are problematic. Given the stigma associated with the disease, publicly sharing such personal information may result in discrimination or harassment of those under quarantine. Similarly, sharing this information with private companies in the absence of a legal basis or clear terms of service and privacy policies suggests that companies may hold on to this data and use it for unrelated purposes later on, without the person’s knowledge or consent.

The use of drones to enforce quarantine also appears to be without any legal basis. Individuals are at the risk of being surveilled remotely, without their knowledge or consent, and with little information about who is operating these drones and how they will use the footage collected. Where the police deploy drones, there is danger of such data being retained in perpetuity for purposes entirely unrelated to disease surveillance.

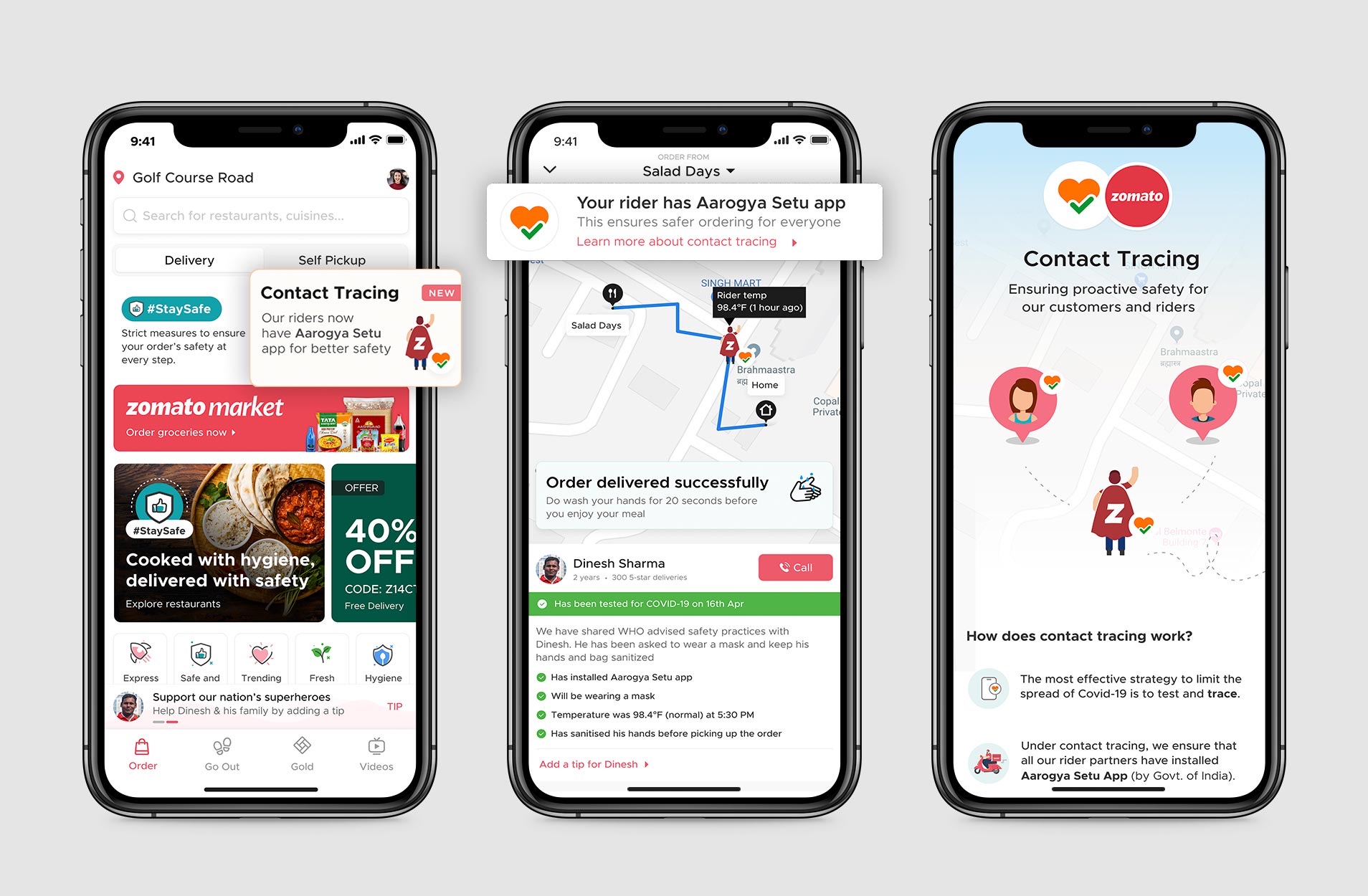

Similarly, Aarogya Setu, the application being promoted by the central government to carry out contact tracing, relies on cell-phone location data to trace an infected person’s contacts.

Cell-phone location data is inherently revealing: it doesn’t just reveal a person’s movement but also helps determine their employment details, financial status, personal preferences, and even information about other members of a person’s family. The app’s policy states that information will be stored on a centralised government server, and is extremely vague about how long this data can be retained, raising concerns about its usage once the pandemic is over.

Nearly three weeks into a nationwide lockdown, the Centre—for the first time—issued an advisory, warning people against sharing personal details of those under quarantine. It remains unclear whether this advisory applies to state agencies too and how it will be enforced.

In several states, governments have framed regulations under the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897—a colonial-era law that gives state governments wide discretionary powers to prevent the outbreak or spread of an epidemic. While conferring wide powers on government officers, none of the regulations analysed by the authors had any restrictions on the use of data or any other procedural safeguards oriented towards privacy.

Even once the epidemic blows over and strict enforcement is no longer required, governments and researchers may continue to legitimately require data to understand the disease better, to address infrastructural gaps or for development of vaccines.

On 27 March, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare announced a four-year long ‘India COVID-19 Emergency Response and Health Systems Preparedness Project’ to study its response to the COVID-19 threat and strengthen its national systems for better preparedness. The Project will necessarily depend on data from testing facilities and hospitals; this will inevitably include personal data of those tested, quarantined, recovered and hospitalised. However, the preliminary plan released by the Government makes no mention of the practices to be followed for the collection and use of data, how long it can be stored and whether safeguards,such as anonymisation or pseudonymisation, will be applied to the datasets before use.

Reality Vs Privacy: What Could, Should Be

The right to privacy in the context of healthcare services has long been recognised in India.

Early in 2020, the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, was in the news, in the midst of a broader push towards a legal framework around the right to privacy in India. This proposed law deals with the collection, storage and processing of personal data. This Bill also recognises the need for appropriate exceptions to the data collection process in the case of public health or medical emergencies.

Similarly, discussions around the use of digital technology and data to improve healthcare systems, and particularly disease surveillance and control are not new in India. The National Centre for Disease Control, and its Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme have been looking into this since at least 2007. An Integrated Health Information Platform was established in 2018, after a review of existing systems in 2015.

However, much of the discussion around the use of technology for surveillance to respond to the Covid-19 crisis does not seem to account for the disease-surveillance plans that have been in place prior to the crisis.

On the one hand, there is talk of the nationwide deployment of tracing technology, without information about the privacy impact on large sections of the population or indeed their ability to access this technology. On the other, we see that the limited procedural requirements we do have in place to facilitate public-private partnerships, appear to be abandoned in the rush to find solutions. Across the board, the call to develop and use new technology and data to respond to this crisis, appears to be divorced from the ongoing efforts discussed above.

A preliminary look at the documentation around existing disease surveillance programs suggests that privacy and data-protection concerns have not been prioritised in these discussions. In addition, it appears that disease-surveillance measures are no longer limited to those provided for under existing legal and policy frameworks.

Personal information is being indiscriminately collected, shared and used by multiple agencies, including state police and private players. Collectively, these entities not only have access to people’s sensitive health information, but also information about their location, whether they broke quarantine, and in some cases, a database of their photographs.

There is little clarity on what happens to this data once the pandemic ends. The absence of an overarching data-protection legislation does complicate things but does not grant states a free license to adopt any and all measures in the garb of public health.

It does not mean that extraordinary surveillance measures taken to combat the epidemic can be normalised either. As we move forward in dealing with this crisis and preparing for the future, we must remember that human rights, including the right to privacy, go hand in hand with public interest.

(Kritika Bhardwaj is a lawyer and a Fellow at the Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi. Smitha Krishna Prasad is Associate Director at the Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi.)