New Delhi, Hyderabad and Cambridge: Imagine an area 80% larger than Delhi, the nation’s capital. That is how much India’s forests grew over a decade, according to a leading United Nations body.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), whose remit is to lead international efforts to defeat hunger and improve nutrition and food security, in a 2024 report, lauded India for gaining 2,660 sq km of forest area between 2010 and 2020, ranking it third globally in increasing forests during this period.

The FAO’s report relies on data from the Forest Survey of India (FSI), run by the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC), the official ‘National Correspondent for India’. These data are not independently assessed by any other organisation.

In May 2024, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed at the United Nations Forum on Forests that India’s forests increased consistently over 15 years, from 2008 to 2023, basing this, too, on FSI reports.

According to the FSI’s 2021 India State of Forest Report, forests grew by 1,540 sq km, when compared to its 2019 report.

Yet, other reports say India’s deforestation levels are second only to Brazil’s.

Global Forest Watch, an online platform run by a global think tank, reported that between 2001-2023, India lost 23,300 sq km of tree cover, an area larger than the state of Meghalaya.

Between 2013 and 2023, 95% of deforestation occurred within natural forests. The National Green Tribunal (NGT), on 20 May 2024, noted this and asked the ministry of environment and forests for an explanation.

“1,73,396 hectares of forest area (1,733 sq km) has been lost due to development activities,” environment and forest minister Bhupendra Yadav told Parliament on 8 August 2024.

The loss appears to be particularly acute in the northeast, which contains 23.75% of the country’s forests, and some of its richest and most biodiverse. The FSI recorded a 1,020-sq-km forest loss across the eight northeastern states between its 2019 and 2021 reports.

These inconsistent reports and conflicting data have widespread implications for India’s ecological security, and call into question India’s climate commitments at the Paris Agreement in 2016, such as creating an additional carbon sink of trees that could absorb 2.5-3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2030.

What The Forest Survey Should Do

The FSI is supposed to assess and monitor the country’s forest resources regularly and publish the results of these surveys. However, the latest report published was in 2021. The 2023 report has been delayed for a year.

The country’s forests are monitored, managed and protected largely under the guiding principle and framework of the National Forest Policy of India, 1988. The policy emphasises the need for conservation and management of forests, protection of wildlife and the involvement of local communities in forest management.

The National forest Policy aims for 33.3% of land in the plains and 66.6% in the hills to be covered by forests, for environmental stability and ecological balance and security.

The FSI’s 2021 report says that 713,789 sq km, or 21.71% of the country, is covered by forests.

FSI reports are vital for monitoring forest ecosystems, planning conservation actions and evaluating progress against national and international commitments.

However, a careful study of the reports reveal that they are based on unverifiable, incomplete and inconsistent data, gathered using questionable methodology.

What The Forest Survey Does Is Misleading

The FSI’s forest assessments use automated algorithms to analyse satellite imagery, which fail to distinguish between native forests and planted orchards.

In 2001, the FSI defined “forest cover” to include “all patches of land with a tree canopy density of more than 10% and an area greater than one hectare, regardless of land use, ownership, or tree species”.

This means private plantations, orchards and even urban parks, such as Lodhi Garden in Delhi or Bangalore’s Cubbon Park may be counted as forests and classified as such alongside native forest ecosystems.

So, the government claim that forests cover 21.7% of India is true under its redefinition of forests, but this includes monocultures of exotic and commercial species under private ownership. These have limited value for endangered wildlife and other ecosystem functions and misrepresent the extent of forests in India.

The assessment is also a gross exaggeration, with no on-the-ground observations or verification that excludes plantations of rubber, palm oil, coffee and tea, amongst others, from “forest cover”, to use the official term.

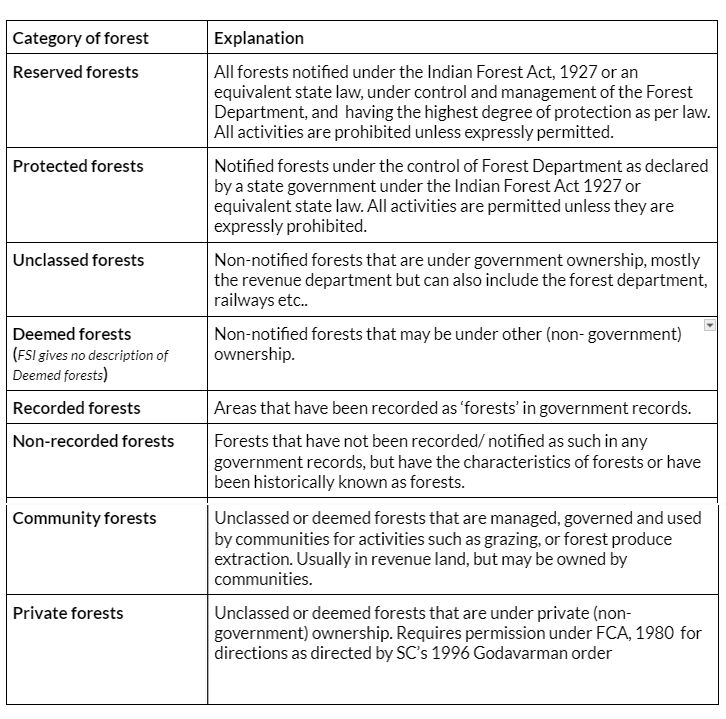

Forests are officially divided into reserved forests, protected forests, unclassed forests, deemed forests, private forests, community forests, recorded and “non-recorded forests” (definitions in table below).

While reserve forests and protected forests are governed by the forest department, unclassed forests are under various other government departments, most often the revenue department.

Ignoring The Supreme Court

A 1996 Supreme Court directive, called the Godavarman order, directed state governments to form state expert committees (SECs) to identify “forests”, whether notified, recognised or classified under any law, irrespective of who owned the land.

The Supreme Court also directed that all such forests be brought under the purview of the Forest (Conservation) Act (FCA) 1980 .

Similarly, the Supreme Court’s July 2011 Lafarge order directed that district maps of forests, with locations and boundaries, should be prepared for the purpose of the FCA 1980. It ordered the FSI to prepare topographical sheets, in a digital format, with district-wise details of changes to forested areas.

These landmark orders were meant to ensure that all forests would be legally identified.

However, an analysis of the SEC reports, uploaded by the environment ministry, only after a 19 February 2024 Supreme Court order forced them to, showed that non-notified forests, or any other forests besides “reserved and protected forests” covered under the Godavarman order, have not been identified. Indeed, there is no mention of the data based on forests identified by the SECs in the FSI reports.

The India State of Forest Reports do not classify, map or provide details of deemed forests, private forests or unrecorded forests, as the Supreme Court’s 2011 Lafarge decision ordered them to do.

The non-compliance with SC orders results in the exclusion of large tracts of forests from legal protection. According to the 2021 FSI report there is an estimated 197,159 sq km of forest land that lies outside the recorded forest area.

This estimation probably includes unclassed forests and amounts to approximately 27% of India’s forest land. It will lose legal protection under the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act (FCAA), 2023, which has been challenged in court.

Even this, though, could be an underestimate given the history of poor assessments of forests.

Incomplete Assessments

FSI reports record the expanse of reserve and protected forests, and, to some extent, unclassed forest areas. They do not identify or map any other type of forest.

This indicates that the data on unclassed forests is obtained only from state forest departments and not others that own forest land, making it likely that unclassed Forest areas are grossly under-assessed.

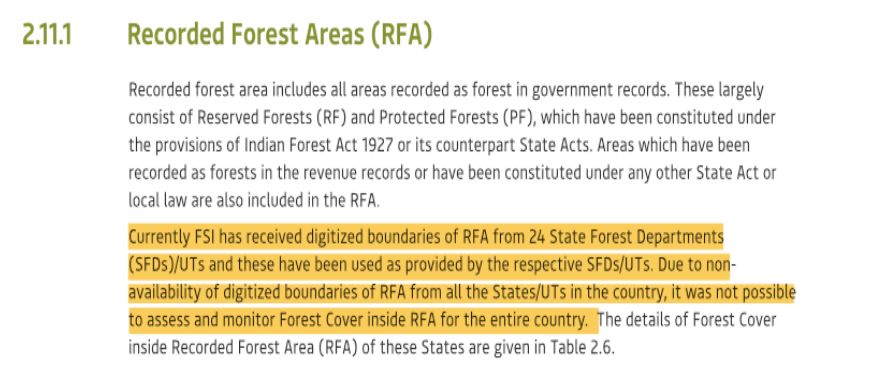

By FSI’s own admission “only 24 out of 36 states/UTs have provided the boundaries of recorded forest areas” for classification.

The FSI began recording unclassed forests in its reports from 1995 onwards, but there is no way to verify if this information is accurate because the reports do not provide any accompanying georeferenced maps to show the location of these forests.

This means that there is no way to track how these areas are being used and determine if they have been encroached.

Inconsistent Data

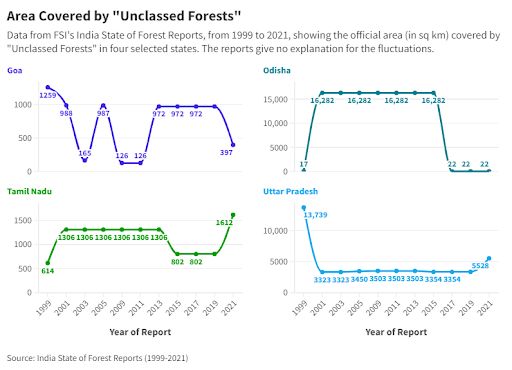

Our examination of state-wise forest data, recorded in FSI reports from 1999-2021, unearthed several inconsistencies in the area of unclassed forests, calling into question their veracity.

In the data for Odisha, for example, unclassed forests increased from 17 sq km in the 1999 FSI report to 16,282 sq km in the 2015 FSI report, only to fall to 22 sq km in the 2017 report, with no explanation.

FSI’s reports similarly show that Goa had 1,259 sq kms of unclassed forests in 1999. This number dipped to 165 sq km in 2003 and then rose to 987 sq km in 2005, before yo-yoing to 126 sq km in the 2009 & 2011 reports. The area covered by unclassed forests in the state again rose to 972 sq km in 2013 before dropping to 397 sq km in FSI’s 2021 report.

The reports offer no explanation for these swings in the data for Goa’s unclassed forest cover. Data for Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Jharkhand show similar discrepancies.

Delhi and Kerala’s records claim that the two states have no unclassed forest area, which could mean either failure of the states to supply data to the FSI or a complete lack of unclassed forest areas, which is unlikely.

What is more likely is these states have evaded the recording of unclassed forests to circumvent legal safeguards, as Kerala did, in order to divert unclassed forest land for non-forestry purposes, without the approval of the central government, as mandated by the FCA 1980.

One instance concerns the Chinnakanal Unreserve—terminology for forests on revenue department land—in Munnar, an important elephant corridor that ought to have been identified by Kerala’s SEC. It was not, however, included in the SEC or FSI data and is today overrun by commercial tourism and witnesses frequent human-elephant conflict.

One instance of the conflict was the tragic story of Arikomban, a wild elephant that had been captured twice, tranquilised many times and relocated from its forests–now a dense human habitation—to deflect the conflict.

Such inconsistencies exist in many other states, such as West Bengal, which showed no change in unclassed forest area over a 26-year period, from 1995 to 2021. This claim is questionable considering the large-scale development activities—typically on forest land—across the country.

The absence of verification and the reporting of such inconsistencies reveals how the premier institute mandated to collect and map forest data conducts its operations.

The lack of verification, to determine if these areas are indeed still forests, undermines the credibility of the data. The lack of court-mandated geo-referenced maps leaves no scope for reconciling FSI data and government records with reality.

Loss of Native, Natural & Hill Forests

While the FSI reports claim an increase in forest cover, scientific assessments from as early as 2010 indicate that native forests have been declining. According to Global Forest Watch, from 2013 to 2023, 95% of trees lost in India were within natural forests, 16% (2,410 sq km) of which were primary forests.

Another problem is the singular focus on meeting the national forest policy’s target of 33.3% forest cover, while overlooking the guideline, within the same policy, which stipulates a 66.6% forest cover in hilly regions. The 2021 FSI report records a decrease of 902 sq km in 140 hill districts, with forest cover in these fragile regions dropping to 40.17%, much below the forest policy’s target.

The specific, and critical, requirement for higher forest cover in ecologically sensitive hilly regions has been ignored, not only misrepresenting the health of India's forests and neglecting the vital role that montane forests play in biodiversity conservation.

Deforestation in mountains has led to multiple disasters, the most recent being tragedies in Kerala, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

Implications Of Bad Data

Since the FSI’s reports do not provide clarity on India’s forests, we do not know where many of our forests are, what their status is, who owns or governs them, whether they are legally protected, and if they have been lost —encroached, cleared or used to build buildings, hotels, dams and malls.

The inconsistent and conflicting data provides loopholes for the diversion of forests, avoiding the multi-layered scrutiny required by both the FCA, 1980 and the amended law of 2023, the latter criticised for diluting these safeguards.

Often, the government claims that the loss of forests is offset by compensatory afforestation, where new forests are supposedly created to replace the loss of old ones.

Environment minister Bhupinder Yadav in August 2024 said 21,761 sq km of forests had been “acquired” under “compensatory afforestation” to make up for the 1,733 sq km that had been lost over the “last 10 years”.

This is a contentious claim, as the new forests are often unclassed or other forests, handed back to the government or forest department after so-called afforestation. Under the SC’s 1996 Godavarman order, such areas should have been counted and notified and would qualify as forests.

These plantations, as the FSI’s 2021 report itself indicates, only contribute about 4% of India’s current carbon stocks (stored as above-ground biomass). Plantations or created forests have also been criticised by the government’s auditor, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, for implementation failures, doubts over long-term survival and the misuse of funds.

As we await the delayed 2023 FSI report, the reliance on misleading data to meet national and international commitments raises significant concerns for the fate of the country’s forests.

India has many critical biodiversity hotspots within its boundaries and assessing native, exotic, primary, and degraded forests under a single umbrella obscures the true picture of the status of the country’s forests, biodiversity and wildlife and carbon sequestration.

It also undermines India’s international commitments to biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation. This can hamper the country’s credibility on the global stage—the United Nations has already questioned India’s forest data—affecting international cooperation and funding for conservation efforts.

The Way Forward

Protecting natural forests and restoring degraded forests rather than promoting plantations and inferior greening drives, as proposed by the 2023 FCAA, should be a central component of climate mitigation and biodiversity conservation policies and strategies. Here’s how that can be done, sequentially:

- Reconcile government records of forest areas from 1997 with existing FSI assessments and verify them on the ground.

- Create a database of unclassed, non-notified forests, unrecorded forests using private and community records of recorded and unrecorded forests at the district and state level from 1997, as the Supreme Court’s 1996 Godavarman order required.

- Once these data are obtained and verified, all land diverted for other uses should be reclaimed, as far as possible.

- As deterrence, act against officials who allowed forests to be illegally diverted.

- Unclassed and other forest areas, which as per the Godavarman order, should be officially recorded as forests and legally protected under the Indian Forests Act or relevant state laws.

- All forests should be brought under the scrutiny of the FCA 1980, which will depend on what the Supreme Court says on a petition that challenges the constitutionality of the amended FCA.

(Prakriti Srivastava is the former principal chief conservator of forests, Kerala, and the former deputy inspector general (wildlife) in the environment ministry. Krithika Sampath is a conservation researcher and Prerna Singh Bindra is a former member of the National Board for Wildlife.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.