New Delhi: The government misled or lied to parliament in 2019 and 2020, according to right-to-information (RTI) documents provided to us, suggesting a pattern of withholding information to Parliament ahead of the abrogation of Question Hour for the first time in 44 years after the Emergency.

In documents provided by the Union Ministry of Tourism and the Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) Tourism Department, declines in tourism in Jammu and Kashmir were either not revealed or manipulated in responses given during Question Hour over two sessions in 2019 and 2020. Some members of Parliament (MPs) told Article 14 that this fits a larger pattern of undermining Parliament, and a former secretary general of the Lok Sabha, the lower house, said he had never before encountered a minister deliberately lying in the house.

On 3 September, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) National Media Head and Rajya Sabha (the upper house) MP Anil Baluni defended the suspension of Question Hour over the monsoon session (14 September to 1 October), claiming a “paucity of time”, since Parliament would function for only four hours each day, in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, a move criticised by opposition parties and civil society.

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) Lok Sabha MP Kanimozhi tweeted that “even elected representatives have no right to question the government”, while Congress’s MP from Shri Fatehgarh Sahib, Dr Amar Singh, pointed to the irony of the government forcing thousands of students to write exams during a pandemic but suspending Question Hour.

The suspension is not the only way the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has chipped away at the accountability mechanisms of Parliament, as our investigation through documents about tourism in Kashmir—or the lack of it—obtained under the Right To Information Act, 2005, reveal.

How Government Lied Or Misled Parliament Over Kashmir Tourism

In March 2020, Gaurav Gogoi, a Lok Sabha MP of the Congress party asked the Union tourism ministry:

“whether it is true that total tourism in Jammu and Kashmir has reduced by 84% in October, 2019; (b) if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefor; (c) the plans of the Government to boost tourism in the said State in the coming months; and (d) if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor?”

The tourism ministry sought information for Gogoi’s question from the J&K Tourism Department, according to the documents we obtained under RTI. On 18 March, the J&K Tourism Department confirmed “a decline of 83.33% of tourists footfall [sic] in Kashmir during the month of October 2019 in comparison to October 2018”. It also reported a 3% decline in “tourist footfall” in Jammu division, attributing the decline in both Jammu and Kashmir to the “law and order situation”.

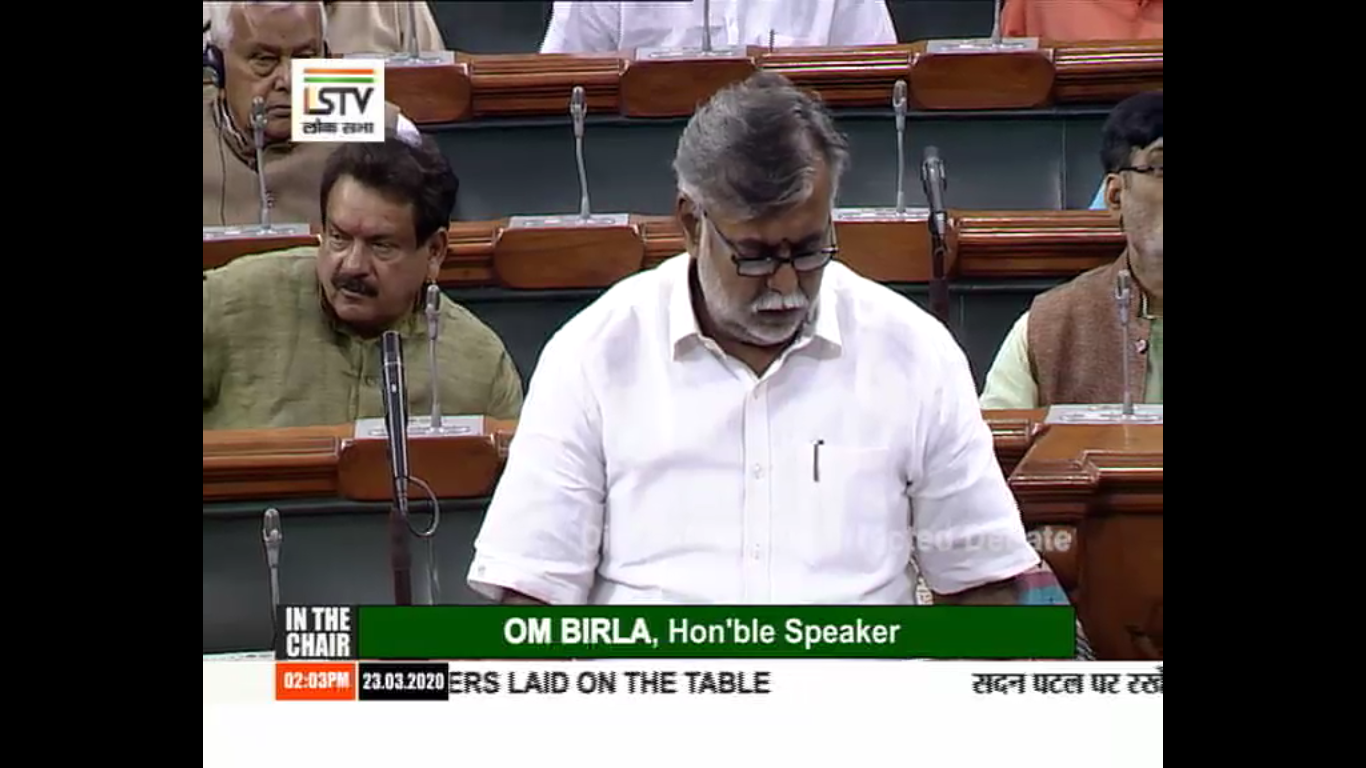

Union Tourism Minister Prahlad Singh Patel withheld this information in his reply to the Lok Sabha on 23 March 2020. He said:

“As per the data received from Jammu and Kashmir UT Administration, number of guest checked in the areas under Jammu and Kashmir Divisions during August, 2019 to October, 2019 are as under:

In August 2019, 20191008748 guest checked in.

In September 2019, 20191123931 guests checked in.

In October 2019, 20191277673 guests checked in.

The above data shows that there was no decline in October, 2019 as compared to September, 2019. However, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India has not made any specific study regarding decline in tourism in J&K or the reasons thereon.”

A Pattern Of Misleading Answers

The government ordered tourists out of Kashmir on 2 August 2019, even suspending a Hindu pilgrimage, the Amarnath Yatra. The order banning tourists was in place until 9 October 2019.

AnRTI-based investigation by Muzamil Bhat and Chitrangada Choudhury showed that the J&K tourism department had compiled month-wise figures for tourist arrivals, and they indicated a fall of 86% for Kashmir.

The answer given to Gogoi was not the first time the tourism minister misled Parliament, as the government pushed a narrative of “normalcy” (here and here).

In November 2019, Communist Party of India (Marxist) leader and Rajya Sabha MP Elamaram Kareem also asked a question about decline and losses in tourism in Jammu & Kashmir since the abrogation of Constitution’s Article 370, which had laid down the terms governing the accession of the former princely state to India.

In his reply on 19 November, Patel evaded the question of decline and claimed that “information about revenues received from tourism is not maintained”.

Our RTI-based investigation revealed that in this instance too, the tourism ministry had written to the J&K Tourism Department seeking information to answer Kareem’s question. On 15 November, the department replied, revealing an average decline of 71% in tourism revenues in the former state between August and October 2019.

Kareem used revelations in our story to file a Breach of Privilege motion against Patel in February for misleading the House. Responding to the motion, the minister tied himself up in more knots:

“No methodology has been developed by Ministry (sic) of Tourism to estimate revenue received from tourism. It is not known to this ministry whether there is any standard / scientific / authentic methodology of compiling revenue data from tourism. Hence, MoT has not prescribed any methodology to be followed by States/UTs to compile data on revenue generation from tourism. Neither has MoT, GoI authorised any agency to do so since no standard / authentic methodology seems available for the same. In view of this it is not possible for the MoT to recognise/quote/own up at official platforms any compilation of data on revenue received from tourism by any agency foreign or Indian including that received from the government of J & K.”

The government’s contention—that it has no data on tourism revenues, nor is a methodology available to gather it—is false.

Government Denies Its Own Policies And Data

The tourism ministry has been compiling and publishing tourism statistics annually for several years, reporting earnings from tourism, as, for instance, it did to the erstwhile Planning Commission (such as this section on tourism in the 11th Five Year Plan). The tourism ministry’s website even hosts a methodology document to conduct surveys of domestic and foreign visitors numbers and their spending at the district level.

The tourism ministry had even commissioned the National Council of Applied Economic Research, a think tank, to collect data about employment generated, gross value added, and earnings from tourism for states and union territories, and released the findings for Jammu and Kashmir as recently as December 2019.

Minister Patel did not respond to an email questionnaire sent by Article 14 to his office. Dissatisfied with the minister’s defence, Kareem has asked the Rajya Sabha to proceed with the breach of privilege motion.

“They are sabotaging every function of Parliament,” said Kareem. “Last August, they introduced the bill (to abrogate Article 370) on Kashmir, without giving MPs any time to examine it and hold a proper debate.”

Gaurav Gogoi told Article 14 that he had asked the question since tourism is a key provider of livelihoods in the Valley, and months after the abrogation, “things were far from normal despite what the government claims”. Like Kareem, he too said he would file a breach of privilege motion against minister Patel for misleading Parliament.

“There have been some cases of suppressing information, but I have not come across a single instance of a minister lying to the House in my experience of 40 years in the Parliament,” former Secretary-General of the Lok Sabha, P D T Achary told Article 14.

Maansi Verma, a lawyer and founder of Maadhyam, a civic engagement platform that works to bring Parliament and policymaking closer to the public, said they had sent open letters with over 800 signatories to the Lok Sabha Speaker and the Chairperson of the Rajya Sabha against the move.

“The session is being reduced to just carrying out the government’s agenda, with little space for MPs to raise issues,” said Verma. “Every MP is an individual lawmaker and Parliament must be an independent institution free of executive control.”

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh reportedly explained to opposition leaders that Question Hour needed to be cancelled because it requires a large number of officers to be present in the Parliament to brief ministers. However, Verma pointed out that the government was regularly holding online meetings, as well as events such as a ceremony for the Ram temple in Ayodhya, and asked why it could not manage briefings related to Parliament.

Verma argued that the suspension of Question Hour was part of a larger pattern of undercutting Parliament. “Under the cover of the pandemic parliamentary committees have not been meeting,” she said, “and the government has proposed a large legislative agenda in a short session, along with the promulgation of ordinances, which again bypass parliamentary debate and scrutiny, and become a fait accompli.”

The government has proposed as many as 40 bills in the 14 day-long monsoon session in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha. Of these, 12 are new bills and 11 are to replace ordinances, some of which have sparked farmers protests in northern India. As opposition MP in the Rajya Sabha Derek O'Brien wrote in a recent column, the Modi government has a higher rate of issuing ordinances than any previous regime.

A Century-Old Practice Is Suspended

Although the practice of asking questions dates even farther back to the late nineteenth century, devoting the first hour of every meeting of the central legislative assembly to questions began with the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919.

Beginning September 1921, members of what was then the Legislative Assembly of India could demand oral answers to their questions—these were “starred questions”, as they are called even today.

The remaining “unstarred” questions received written answers. Of course, the membership of the central and the provincial assemblies in colonial times was not representative. A significant number of members were nominated, and elections to the remaining seats were restricted to a small fraction of the population.

But even the imperial government of India was answerable to the Legislative Assembly in a way that the present government will not be—for the first time, as we said, in 44 years after the Emergency.

The Question Hour withstood a colonial government and was rescinded only rarely during regular sessions of the Parliament in Independent India— in times of war and in two of five sessions during the Emergency. In the Golden Jubilee Commemorative Session of the Lok Sabha in 1997, the House unanimously adopted a resolution to “maintain the inviolability of the Question Hour,” among other commitments.

Reflecting this emphasis, the government’s Manual of Parliamentary Procedures, last issued in July 2019 by the ministry of parliamentary affairs, requires that replies by the government to be “as precise, unambiguous and complete as possible, taking particular care to avoid expressions which are liable to be construed as evasive…. As far as possible, each part of the question should be answered separately”.

The website of the Lok Sabha notes:

“Asking of questions is an inherent and unfettered parliamentary right of members. It is during the Question Hour that the members can ask questions on every aspect of administration and Governmental activity. Government policies in national as well as international spheres come into sharp focus as the members try to elicit pertinent information during the Question Hour. The Government is, as it were, put on its trial during the Question Hour and every Minister whose turn it is to answer questions has to stand up and answer for his or his administration's acts of omission and commission.”

The government’s move to cancel the Question Hour is “absolutely unconstitutional” and “defeats the entire purpose of Parliament”, according to Achary. He said Parliamentary questions draw their sanction from Article 75 of the Constitution which makes the Council of Ministers collectively responsible to the House of the People, and “the executive cannot suspend the right of the house. It is up to the House to decide these matters”.

Question Hour is also important because MPs have considerable leeway to consider diverse issues of public interest, since this is the only time in Parliamentary proceedings where they are not restricted by party whips.

Although there are rules about admissibility, notice period and other aspects of questions, these are not heavily biased against the opposition. A recent compilation of Parliamentary questions over 20 years to 2019, put together by Saloni Bhogale and staff of the Trivedi Centre for Political Data at Ashoka University, showcases the wide spectrum of issues on which MPs have quizzed the government.

The information that comes into the public domain via ministers’ responses in Question Hour is additionally significant given that the Prime Minister has not held a press conference in the six years since he assumed office, and the government has undermined the RTI.

In a tweet, former Rural Development Minister Jairam Ramesh said that in his eight years as minister, “I looked forward to Question Hour . . . welcomed the grilling and used the opportunity to share maximum information on policy and programmes, and get feedback from the Members.”

Gogoi said: “In the name of the pandemic, they first they took away MPLADS funds (the MP Local Area Development Scheme, a fund available to MPs to spend on public works in their constituency ), and now they are doing this with Question Hour—it is a brazen attempt to centralise all power and undermine the role of representatives of the people and undermine accountability.”

The criticism led the government to say that it will allow unstarred questions, but these do not allow for follow-up questioning, as MPs like Kareem and Derek O’Brien told Article 14.

“As the J & K tourism issue shows, the ministers are often giving answers which are incorrect or misleading," said O'Brien, the All India Trinamool Congress’s Floor Leader in the Rajya Sabha. "In Question Hour, I have the right to ask two supplementary questions. My right to do that gets suspended too if Question Hour is suspended.”

(Aniket Aga is an academic at Ashoka University. Chitrangada Choudhury is an award-winning journalist and member of the Article 14 editorial board. She works on issues related to the environment, indigenous and rural communities and the right to information.)