New Delhi: When Prime Minister Narendra Modi broke his silence on Delhi 2020, two days after violence first broke out in north-east Delhi, leaving at least 30 dead and hundreds wounded, it was strikingly similar to the peace appeal he made in Gujarat 2002 in at least one key respect.

Neither of the statements condemned the violence targeting Muslims or acknowledged—despite evidence—police complicity.

The operative part of Modi’s two tweets on 26 February 2020, two days after the eruption of violence in north-east Delhi, was a request to the public to “maintain peace and brotherhood at all times”. Modi did not mention the attacks even on Hindus and police personnel.

In his earlier avatar as chief minister, Modi responded more promptly to the Gujarat violence by issuing a peace appeal through Doordarshan (see above) on February 28, 2002, the day after 59 Hindus—of these seven were never identified—returning kar sevaks from Ayodhya, were burned alive at Godhra railway station.

Modi mourned the casualties at Godhra and promised action against the perpetrators, although by then the number of Muslim casualties in the retaliatory violence greatly exceeded those killed in Godhra. Modi did not ever refer to the killings of Muslims.

By the time he recorded his peace appeal at 6 pm in Ahmedabad’s Circuit House Annexe, the first post-Godhra killings had already taken place, over two hours earlier at 3.45 pm, barely 3 km away at the largely Muslim residential complex, Gulberg Society. In 2016, a trial court convicted 24 accused in the Gulberg Society massacre, sentencing 11 of them to life imprisonment. Gulberg Society saw the first of a series of state-wide incidents of violence, in which eventually 800 Muslims and 200 Hindus died.

The Supreme Court-monitored investigation of a complaint—seeking political and administrative accountability—from Zakia Jafri the widow of Gulberg Society victim and former Congress Member of Parliament Ehsan Jafri, cleared Modi without questioning him on, among other things, why his Doordarshan message at that sensitive stage had displayed selective outrage.

There were allegations of a cover-up, given the cursory manner in which the special investigation team (SIT) questioned Modi, asking him when exactly he had come to know about the attack on Gulberg Society. Modi claimed he had no idea about the attack on Gulberg Society till he was informed at a meeting that took place in his Gandhinagar home later that evening at 8.30 pm. The SIT did not ask any follow-up questions.

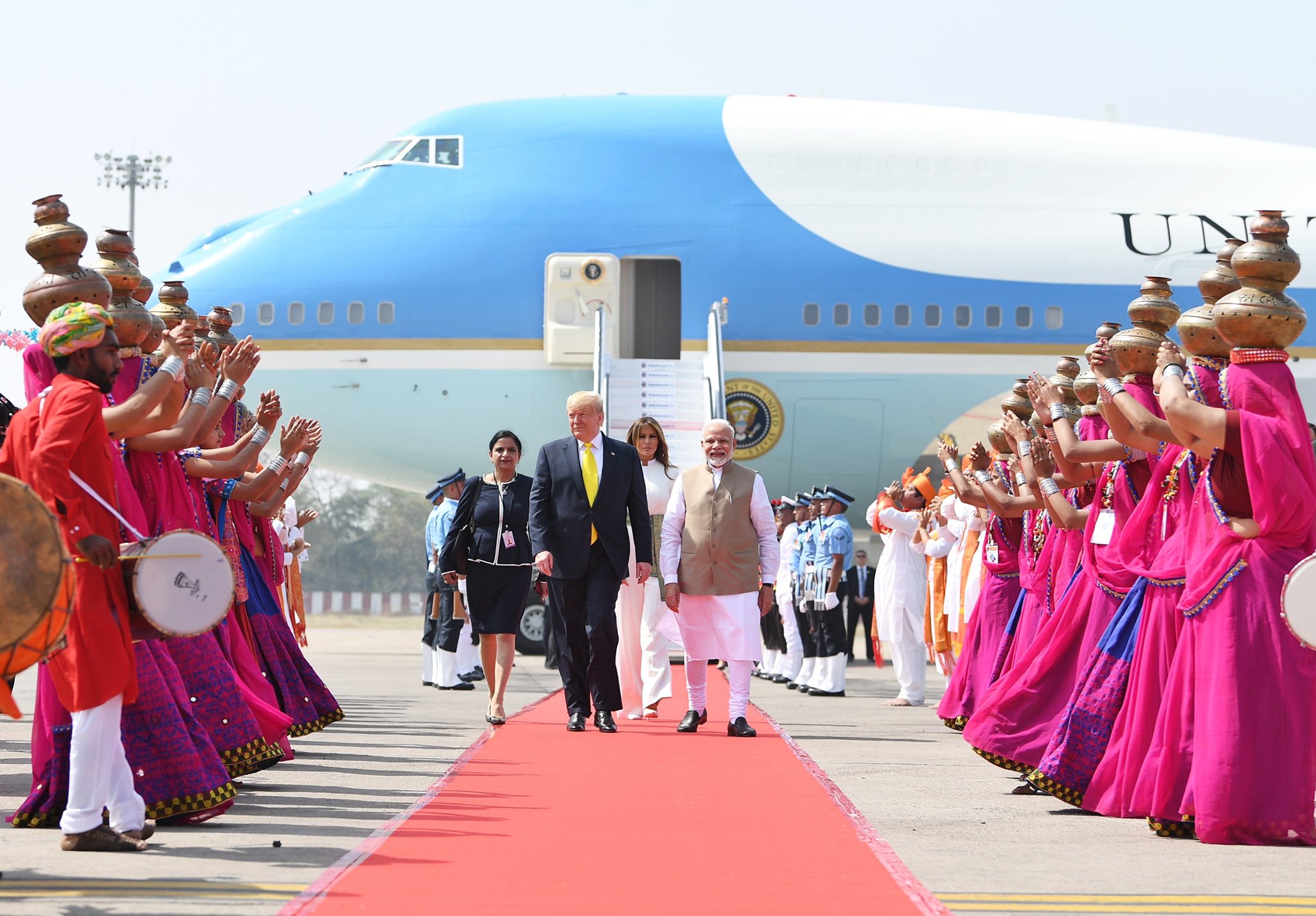

The disclosure made by American President Donald Trump on Tuesday about the discussion he had with Modi on “religious liberty” threw up another parallel between Delhi 2020 and Gujarat 2002.

Modi’s failure in 2002 to acknowledge police complicity became more evident in December 2019, when a report from a commission headed by Justice G T Nanavati was tabled, 17 years after it was constituted, indicted M K Tandon, the police officer in charge of the area in which Gulberg Society was situated.

‘A Very Powerful Answer’

In what Trump described as “a very powerful answer” from his host, Modi apparently told him that while there were 200 million Muslims in India, “a fairly short while ago, they had 14 million”.

Even if Trump’s recollection of the earlier population mentioned by Modi was inaccurate—and this has not as yet been denied by the Prime Minister’s Office—the conversation indicated that the Prime Minister had responded to religious-freedom concerns by referring to one of the pet peeves of his Hindutva supporters: that the population growth rate of Muslims across the country was higher than that of Hindus.

This was the dominant theme of a contentious speech Modi delivered at Becharaji on 9 September 2002 during a gaurav yatra (or journey of pride), which he had launched to protest the Election Commission’s refusal to hold polls in the state as early as he desired in the aftermath of the riots. He was upset that among the grounds cited by the Commission was the reluctance of riot victims to leave relief camps.

Referring to his policy of shutting down relief camps, Modi said they were “child-producing centres”. The insinuation was that Muslims, were procreating in relief camps. This was followed by a swipe at Muslims for their alleged aversion to family planning.

“We want to firmly implement family planning. “Hum paanch, humare pachees (We five, our 25),” Modi said with a laugh, referring to the freedom that Muslim men have under their personal law to have as many as four wives. “Who will benefit from this development? Is family planning not necessary in Gujarat?”

“If we raise the self-respect and morale of five crore Gujaratis, the schemes of Alias, Malias and Jamalias will not be able to do any harm to us,” said Modi.

When the SIT asked him in March 2010 about the alleged hate speech in Becharaji, Modi’s defence was: “The speech does not refer to any particular community or religion. This was a political speech in which I tried to point out the increasing population of India, in as much as I stated that ‘Can’t Gujarat implement family planning?’.”

In its preliminary report to the Supreme Court in May 2010, the SIT headed by former CBI chief R K Raghavan made this observation on the Becharaji speech: “The explanation given by Modi is unconvincing, and it definitely hinted at the growing minority problem.” But after the Supreme Court had ceased to monitor its investigation, the SIT in its closure report to a magistrate in Ahmedabad in 2012 said: “No criminality has come on record in respect of this aspect of allegation.”

(Manoj Mitta is a member of the editorial board of Article-14.com and the author of two critically acclaimed books on sectarian strife in India, The Fiction of Fact-Finding: Modi and Godhra, and When a Tree Shook Delhi: The 1984 Carnage and Its Aftermath.)