Updated: Aug 16, 2020

New York: The custodial torture and deaths of father and son duo P Jayaraj and J Bennix in Tamil Nadu on 22 and 23 June, 2020, have again focused attention on torture in India. The outrage and protests led the Madras High Court to intervene and a judicial magistrate’s report and autopsy enabled the arrest of all the involved policemen.

The swift reaction in this horrific case of police brutality is in contrast to a larger pattern of impunity that exists regarding custodial deaths and custodial torture in India.

An average of five people die in custody—police or judicial—every day in India, an unknown number tortured, according to India: Annual Report on Torture 2019. Although investigations were launched into the death of 500 people who allegedly died of torture in police custody, there was no conviction over 13 years to 2018.

In the Indian legal context, there are significant safeguards to prevent police violence during police investigation and interrogations. The immense scrutiny into custodial deaths during investigations has even led to the emergence of forensic psychology as one of the possible solutions to torture.

Despite this, the continuing ability of the police to torture, in the context of investigations and interrogations, allows them to use such methods more generally, often to punish, coerce and discriminate with impunity.

The UN Convention against Torture states: “The term ‘torture’ means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.”

Thus, torture is used for confessions/information, punishment, intimidation, and discrimination.

In the Jayaraj and Bennix case, the police may have initially arrested them to either enforce a Covid-19-related lockdown or some other dispute, but the act of torture in police custody clearly is linked to punishment or intimidation, or simply an assertion of their power in khaki.

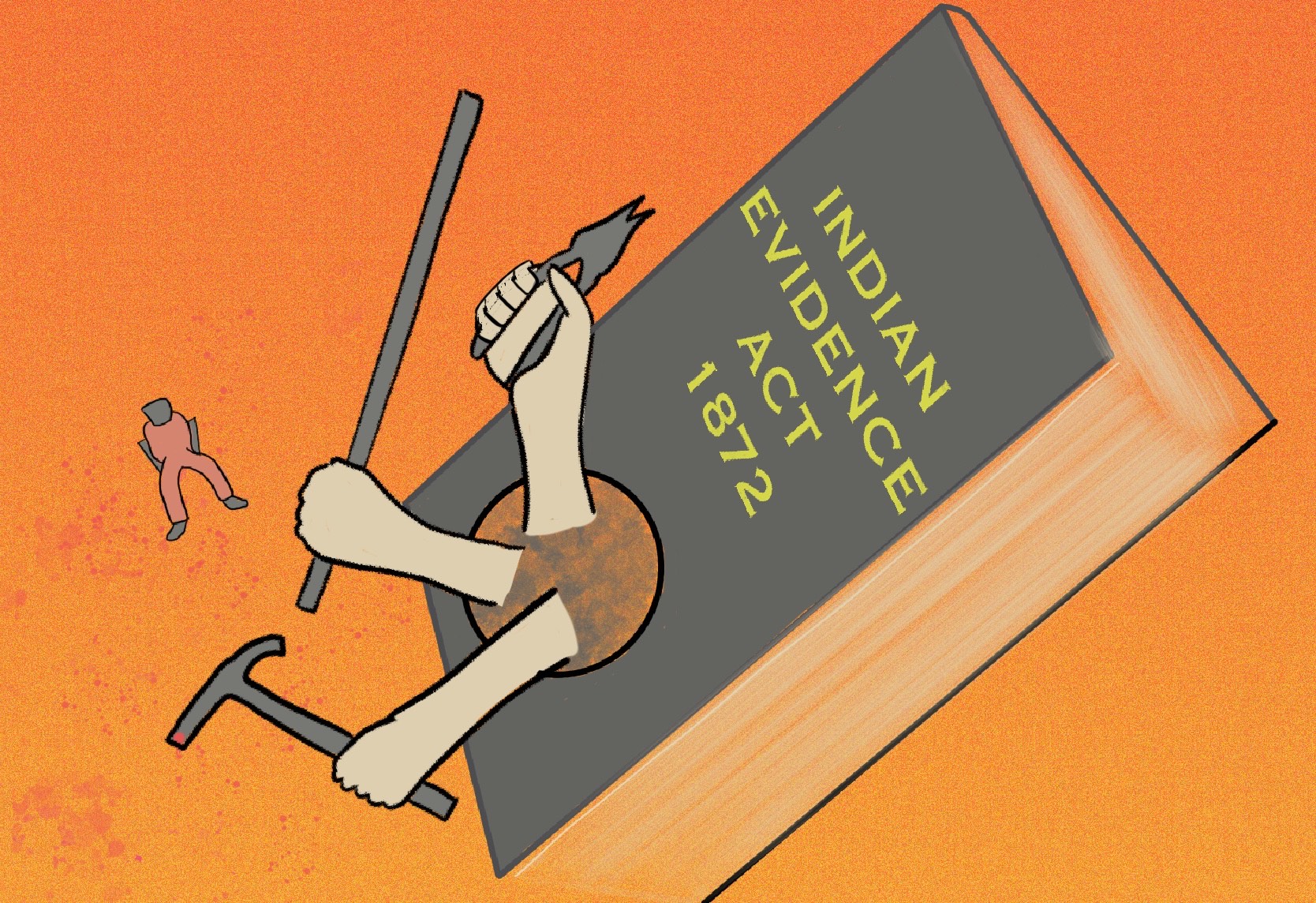

How Torture Is Enabled: Section 27 Of Indian Evidence Act

My 2020 book The Truth Machines illustrates that interrogation to elicit confessions remains a major pretext for the use of torture in India. Even though India has not ratified the UN Convention against Torture (although the country signed it in 1997), a combination of constitutional and statutory safeguards does represent legal protection against torture.

In particular, the landmark DK Basu case (1996) and its safeguards of an arrest memo to avoid illegal detention, regular medical examinations, right to a lawyer were considered important to prevent the use of torture and custodial deaths. However, as the amicus curiae in the Basu case himself admits, these have not been adequately implemented.

The law in India does not permit any confession based on “inducement, threat or promise” to be used in criminal proceedings. The law also makes any confession to the police inadmissible in criminal trials. These provisions are meant to be safeguards against police torture.

However, the law does allow materials recovered as a result of confessions to be included as evidence under section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. The police themselves have indicated to me that this provision allows the continuation of torture.

For instance, in one of my interviews, a senior police official based in Mumbai expressed a sentiment echoed by many other police officials: “Now, here a case has come to you of theft, all right. Now I cannot say that my lord, here is the thief. He has admitted before me. The court is not going to accept that, all right. What the court will accept is, if that man says that, look here, I will show you where I have disposed or hidden that property… The law itself is saying that, look here, I’m not going to believe you unless you produce this and that “produce this” is not going to come voluntarily. The law also knows. I also know. The judge also knows that no recovery, no discovery of fact as is known in the legal parlance, can take place voluntarily.”

Another police officer told me that in the absence of high conviction rates in criminal cases, the police in different states mention the recovery rates of such material as proof of their success. According to the police officer, the rate of recovery of property is reported in the National Crime Records Bureau Reports each year and is a point of competition among states.

There are media stories about which state has the highest rate of recovery of stolen goods. For the police, section 27 indicates an existing incentive for the use of torture or third degree (as they prefer to call it).

Why Confessions From Torture Are Unreliable

Confessions as a result of torture are not just violative of human dignity, they are also unreliable.

Darius Rejali, for example, has shown that there is no empirical evidence that indicates the efficacy of torture. In face of such unreliability or inefficacy, the relationship between interrogation, torture and confessions is important precisely because the question during interrogation then becomes the excuse, not motive for torture as Elaine Scarry has famously argued.

In other words, despite the inefficacy of torture, the “desire for information” plays a legitimising role by becoming the pretext for torture. A benefit of doubt is given to the police that they perhaps used torture primarily to get information. Rather than focusing on the violent act, the scrutiny is more on the need for information during the interrogation.

In the process, the interaction between the tortured and the torturer becomes entangled in whether confession or useful information emerged from that interaction, deflecting from both the brutality of an act and dehumanisation of the tortured (especially if from a marginalised community).

If torture can be directly or indirectly legitimised in the context of interrogation, there is possibility of justifying the use of torture in the context of punishment and intimidation. Police are the primary state agents authorised to use force and are given latitude in using their discretion in the use of force.

If, in the context of interrogation, the extraction of information or recovery of materials can be utilised in legitimising torture, violence can also be indirectly used as a discretionary power in maintaining order and the status quo.

The Introduction Of Truth Machines

The 1990s were a major decade for the human rights focus on custodial deaths and torture.

The National Human Rights Commission—constituted under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993—became the primary monitoring body for custodial deaths. India signed, as I said, the UN Convention against Torture in 1997.

These policies were in response to the police excesses of emergency in 1975-77 and the advocacy of civil liberties and democratic rights groups in 1980s-90s. The need to solve the problem of third degree or torture that plagued the criminal justice system became pressing. And this pressure made investigative agencies turn to technology and science as a solution.

It is at this moment that various techniques that I call truth machines— lie detectors, brain scans (brain fingerprinting and brain electrical oscillation signature test) and narco analysis (use of sodium pentothal) —emerged and eventually consolidated.

While lie detectors had been in use since the 1970s, ambitious forensic psychologists introduced a combination of narco analysis and brain scans in the 1990s and 2000s.

These truth machines came to be seen as indispensable, such that any prominent case in the 2000s—whether Aarushi- Hemraj murder case, Telgi or 2006 Mumbai blast case—ended up with a use or request for these techniques.

The Indian government argued that such techniques would replace physical torture. It insisted that these would promote “scientific investigations” and modernisation. The replacement of physical torture was never really in contention because such techniques were available only in a few forensic science labs.

In suspected terrorism cases or Maoist cases, the truth machines were used alongside physical torture. Yet the argument was adequate for the Indian state to claim an aura of “scientific interrogations”, using experts, such as forensic psychologists, who defined themselves as distinct from the police.

Scientific Experts Inadequate Protection Against Torture

However, despite their efforts to portray themselves as using machines or drugs in a different setting, (notwithstanding the unreliability and invalidity of such techniques), the forensic psychologists merely end up reinforcing yet another site of extracting confessions.

The Supreme Court in its 2010 Selvi decision on forensic techniques mostly focused on the consent for these truth machines and on the inadmissibility of evidence.

The Court could have recognised the continuation of the role of forensic psychologists, which allowed for the extraction of confessions in the infrastructure for the truth machines. The mere use of scientific experts is not adequate protection against the use of torture and coercion. The utilizing of the body to get oral evidence in any form is coercive and in narcoanalysis is a form of pharmacological torture as Amar Jesani notes.

In the absence of an intervention challenging the custodial conditions that enable torture and a continued embrace and desire of the truth machines, the postcolonial Indian state remains peculiar. Its jurisprudence, monitoring institutions, and even legislative process strongly disclaims torture and some strong safeguards exist.

Yet the conditions enabling torture remain unaddressed, in terms of loopholes in the law, and allowing for the use of medical professionals in coercing confessions despite investigations being one of the most examined arenas.

The Jayaraj-Bennix case, thus, illustrates the need to challenge torture in all its different justifications for impunity—confessions, punishment, discrimination and coercion.

(Jinee Lokaneeta teaches political science and international relations at Drew University, USA, and is the author of The Truth Machines: Policing, Violence and Scientific Interrogations in India.)