Updated: Sep 14, 2020

Noida: “What is at stake is not merely democracy in this country, what is at stake is culture and civilization itself.”

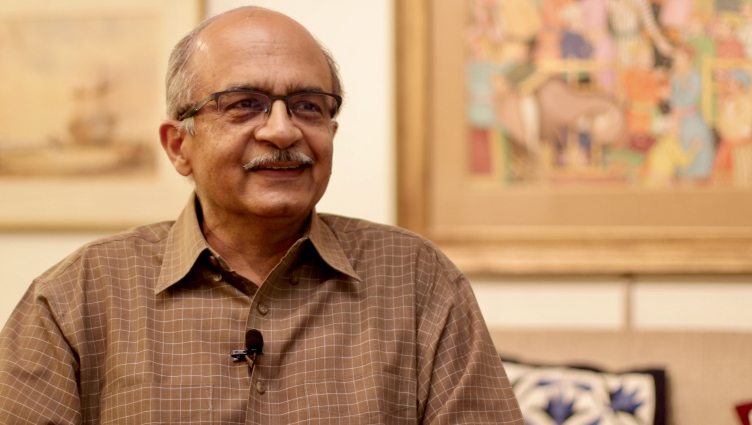

In his trademark plain-speaking style, Prashant Bhushan minced no words as he spoke to Article 14 about India’s illiberal atmosphere, its government and its judiciary.

“This attack on critical thinking and scientific thought, as well as the peddling of fake news and hate speech will destroy all of us,” said Bhushan, 64, in an interview at his home in Noida, Uttar Pradesh.

In the national spotlight, after he was fined Re1 by the Supreme Court on 31 August 2020 as punishment for criminal contempt for two tweets in which he was critical of Chief Justice of India S A Bobde and the judiciary. He steadfastly refused to apologize in court, declaring that he considered it “his highest duty” to be critical. Apologizing, he said, would be “contempt of his conscience”.

For over three decades years, Bhushan has campaigned for judicial accountability and represented in court issues of public-interest nationwide, such as those displaced by the Narmada dam in Gujarat, many of the 600,000 people who were affected by the Bhopal gas tragedy in Madhya Pradesh and those opposing a nuclear power plant in Kudankulam, Tamil Nadu.

Bhushan, whose calm, gentle manner masks a steadfast character, is the eldest son of lawyer Shanti Bhushan and the father of three sons. His book, The Case That Shook India, gives an insider’s perspective on a watershed case, Indira Gandhi vs. Raj Narain, 1975, which became the catalyst for the imposition of the Emergency.

In the interview, Bhushan reflects on the side effects of being convicted for contempt of court by the Supreme Court. He also talks of his formative years, the circuitous route he took to the practice of law, his vision of judicial reforms and the one mistake he wishes he could undo.

Natasha Badhwar: Despite the fact that the Supreme Court has held you guilty of criminal contempt of court, the nominal punishment of Re 1 levied is being interpreted as a moral victory for you. How do you process this case and its implications?

Prashant Bhushan: The case has successfully drawn attention to what has been going wrong in the Supreme Court in the last six years. How the SC’s independence has been compromised and how it has failed to do its job of defending democracy and fundamental rights of the people. Another surprising outcome has been that it has emboldened lots of people to speak out. It became a kind of “freedom of speech” movement in the country.

One unfortunate fallout is that it has strengthened the perception of the SC’s collapse as an apex body and in that sense, it has weakened the court further. This is not what I wanted.

This case has highlighted the nuance around freedom of speech and the concept of contempt of court itself. In May, 2017, you publicly endorsed the indictment of Justice C S Karnan, who was similarly found guilty of disrespecting the courts of law after he decided to out the names of 20 'corrupt' judges in a letter to PM Modi in 2017. He spent six months in jail.

Have you had a re-think about your stand on this issue?

Justice Karnan’s case was very different from mine. He was convicted for interfering with the administration of justice—for passing orders from his residence without jurisdiction. He ordered the arrest of Supreme Court judges and asked for them to be produced before him. The allegations he made were wild but in my view that would not have been a case for convicting and sentencing him to prison. But he went beyond this to abuse his judicial office to pass vexatious orders that were clearly without jurisdiction. Ordering SC judges to be brought before him in chains and so on.

That is why in an extraordinary move, a bench of the senior-most senior 7 judges of the SC took up his case and passed that order. Having said that perhaps it was not necessary to send him to prison. It may have been enough to deprive him of judicial work and prevent him from doing what he was doing, which was creating a serious nuisance for the judicial process.

While this punishment of Re 1 is being perceived as a victory for you, it is also a worry that your conviction in a case like this will be used as a precedent to curb the freedom of speech of people and punish them merely for social media posts. This can be very dangerous.

I do not subscribe to the view that nobody can be punished for social-media posts. Social media is also being used as a platform for hateful and fake news designed to create enmity between religious communities. This is a serious offence under the penal code and that should certainly be stopped.

But any comments on the functioning of any institution, however trenchant your criticism may be, cannot be prevented by labelling it as sedition. This is totally wrong.

You see, contempt is of two kinds—civil contempt and criminal contempt. Courts orders are meant to be obeyed and therefore they need a sanction against disobedience. Criminal contempt is also in two parts. One is interfering with court proceedings and with the administration of justice, which also needs sanctions and is a punishable offence. But the second part, which is scandalising the court or lowering the authority of the court—that is problematic. Because that is an offence by speech and we challenge this law as an unreasonable restriction on the freedom of speech. This is a vague and undefined jurisdiction in which judges sit as judges in their own cause. They are the accusers, they are the prosecutors and they are the judge.

It is not a law which is in public interest at all, and, therefore, it has been abolished in the UK, USA and most other countries.

What would you say is the biggest crisis in the judicial system in India today?

We have been running a campaign for judicial accountability and reforms. At the first level, the judiciary is not accessible to common people unless they have lawyers. Procedural laws are too complex. The majority of people languishing in jail are undertrials. They are poor people accused of crimes who cannot afford a lawyer and cannot arrange their own bail.

Secondly, we need much better judges in courts. The process of selection of judges has to be more robust and transparent. Third, we need more courts and more judges so that most cases can ideally be resolved in six months.

Lastly we need more accountability of judges. Impeachment is a totally impractical and political process. We’ve been saying that we need a fully independent, high-powered complaints commission to whom complaints against judges could be addressed.

Accountability of the judiciary is further whittled down by a SC-declared law that no FIR can be registered against judges without the prior permission of the Chief Justice of India. Very often complaints are made against those who are friends of the CJI and those are ignored. Then we have the contempt law that makes it dangerous to criticise the judiciary.

Another problem is that the independence of the judiciary has been threatened by the lure of post-retirement jobs, in which the government does play a role. I am not against post-retirement jobs for judges, but they should be decided by a high-powered body that is independent of the government as well as the judiciary. Retired judges are needed to be part of enquiry commissions but the government should not play a role in this.

Then unfortunately, this government has interfered with appointments. They are stalling inconvenient appointments for years all together. The government has been known to use the agencies—the IB, CBI, Income Tax department, Enforcement Directorate—to target their political rivals, media, business houses, and now it seems that they have also been targeting some sections of the judiciary in order to compromise their independence. All these problems need to be addressed.

What is your take on the power of the master of the roster?

I feel that this is a very vast power, and it cannot be vested in only one person. We filed a petition in the SC saying that this power must be spread out among at least the top five judges of the SC and they should collectively have a system by which they decide which benches should hear which kinds of cases. Then those cases should go randomly to those benches. This pick and choose, which is really there with the Chief Justice is a very dangerous power to vest with one person. Because if you then have control over the CJI as this government seeks to have, then you control the entire judiciary. All politically sensitive cases can be sent to preferred benches in order to be decided in a particular way that the government may want.

As a lawyer you have been supportive of many social justice movements and have chosen to represent people’s interests against the might of powerful corporates and the state. Recently we saw the anti-CAA [Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019] movement, which came to an abrupt halt with the Delhi violence and the Covid-19 pandemic. What do we need for people to rise collectively as stakeholders to protect democracy?

I believe that people must realize what is at stake. What is at stake is not merely democracy in this country, what is at stake is culture and civilization itself. The barbarity, the culture of fake news and unscientific thought and the attack on critical thinking that is taking place today under this regime is something that will destroy all of us.

Everybody has to realise that they must stand above their own egos, their own personal differences and come together to fight this evil. It’s an unprecedented evil that we are seeing today. An unmitigated evil. The country has never seen this kind of an evil regime.

As a people we must be ready to pay whatever may be the cost of standing up against any kind of injustice. The protests against the CAA was a very important movement because people stood up against discrimination towards Muslims by way of this act. It is true that the government has suppressed the movement by engendering riots and then arresting activists accusing them of perpetrating these riots etc. But this is not going to last for long, especially if people continue standing up and speaking out.

We are already seeing that all those cases are collapsing, one after another. Cases against Dr Kafeel Khan, against Pinjra Tod activists and various other cases are collapsing and eventually they will collapse. And if enough people stand up—how many people will they put in jail? How many?

For example, even in this contempt case, literally lakhs of people stood up and started saying the same thing. How many people will they charge for contempt?

In your long career of engaging with socio-political issues of the time, do you look back and regret any decisions? Given a second chance, is there something you wish you could do differently now?

(Laughing) No, I regret not having completed my science-fiction novel, which I had once written in 1984. I had written a first draft but I never got down to rewriting it. But in general, no I don’t particularly regret anything. I am happy that I pursued a convoluted career. I am happy that I got involved in all these public interest issues as well as issues of judicial accountability.

You also joined politics, with the Aam Aadmi Party.

Oh, yes, that’s one thing which I do regret. Yes, you are right. You see, at that time, what happened was—and I didn’t realise it because I was not watching it closely enough—is that this India Against Corruption movement was heavily propped up by the BJP and the RSS. This became clear later on. Unfortunately that movement led indirectly to the rise of Narendra Modi because it destroyed the Congress. It helped the BJP and Modi to come to power, who have emerged as far greater threats to the country, to our democracy, to our whole culture, than the Congress could have been, or was.

So, in that sense, I do regret having not been able to see that the BJP and the RSS were propping it up for their own political reasons. Secondly I also regret not being able to see Arvind’s (Kejriwal) character early enough. I came to that realization that he was totally unscrupulous and willing to use any means much later. I should have seen that much earlier. So in a way I kind of inadvertently facilitated his rise to power and I realise that I have allowed another kind of Frankenstein to grow.

Talking of your own personal history, what made you choose law as a vocation? You had gone to the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), then you went to Princeton to study philosophy. You took a circuitous route in your education before you arrived at law. What was that final inspiration?

My route certainly was very circuitous. I went to IIT Madras, thinking that every science loving student should go to IIT. I realized that engineering was not what I was really interested in, I was interested in physics. Plus at that time I was very homesick because of my kid sister who was two years old at the time. I was very fond of her. So I decided to come back home.

I enrolled for a BA with economics, political science and philosophy in Allahabad University. By this time, I had been introduced to Bertrand Russell and I got quite interested in philosophy as well. During my BA, my interest in philosophy kept growing. I wanted to do an MA in philosophy and a PhD and become an academic philosopher.

But at that time, while I was still studying my BA, Mrs Gandhi’s election case also took place, which I attended because my father, Shanti Bhushan, was the counsel for Raj Narain in that case. I attended the case in the Supreme Court also, and later I attended the habeas corpus case hearings in the Supreme Court. So, I got exposed to law at the very top, so to say, and I found that also quite interesting.

I got a scholarship for a PhD program at Princeton University, and I went to do a PhD in philosophy of science there. I also began to formally study law. Eventually I came back and took my LLB final exams, and became a lawyer in 1983. That was the convoluted route I took before becoming a lawyer.

At the end I found that none of that education really got wasted. If you study anything seriously, all of it is useful in forming your overall perspective and understanding of things. So I found all that education useful in my legal career as well.

One of the lesser known parts of your work is the Sambhaavnaa Institute in Palampur, a residential retreat and workshop space that has offered a lot of support to big and small groups of activists since 2011. What are you trying to achieve with it?

Over the years, in my interactions with some of the finest activists in this country, I realized that a really good activist is one who understands the issue properly and who can strategically engage on that issue—whether it’s about nuclear energy or large dams—with the government and with civil society to steer policies in the direction of public interest. I felt that we need to set up an institute where such activists could be educated and trained in order to steer public policies towards public interests. That was the whole objective of this institute.

You say that the country has never seen this kind of an evil regime before. We not only have to get through the next four years, we have to make sure that we do not have a situation where the electoral system itself is threatened. What is it that we need to do differently at this time to resist?

Firstly, everybody needs to be active at this time. They need to take an interest in what's happening; speak out about what’s happening. It doesn’t take much to see what’s happening, take an interest in it and speak up. Thereafter, we need to plan strategically to take up issues in order of priority and strategic interest and then develop solidarities and organizations and movements, so that those issues can be taken up in an organised and strategic manner. That’s what people need to do.

(Natasha Badhwar is an author and film-maker.)