Chandigarh: It was around 4:30 am when two deputy superintendents of police, one station house officer and about 12 other police personnel knocked on the door of Paramjeet Singh Gazi’s house in Panj Dhera Gazi, a village in Punjab’s Hoshiarpur district.

Gazi, editor of Sikh Siyasat, a website covering issues concerning Sikhs and the state of Punjab since 2006, was not home. The raiding party seized the mobile phones of his brother and wife, returning them later that evening.

“They surrounded the house from all sides,” Gazi told Article 14 over the phone in September, describing the events of 3 April, as narrated to him by his brother over the phone that day.

Gazi said he had told police officials the previous day that he would not be at home.

He was one of at least 14 Punjab journalists who faced police raids and other government action including a ban on social media accounts during Punjab police’s crackdown on pro-Khalistan leader and self-styled preacher Amritpal Singh in the months of March and April 2023.

The raid on Gazi’s house followed a series of actions taken by Punjab police against seven other journalists over a period of two months, which included raids on their houses and summons to police stations.

Police officials did not divulge why Gazi’s house was raided.

Kulwinder Singh Virk, deputy superintendent of police of the Mukerian subdivision, told The Times of India that they visited Gazi’s house upon receipt of “secret information” and that they needed to check the mobile phones of Gazi’s wife and brother.

Article 14 asked Arpit Shukla, Punjab’s additional director general of police (law and order), why so many journalists had been raided. “It is not known to my knowledge,” Shukla said.

Shukla’s refusal to acknowledge the raids in Punjab, governed by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), are in line with a deteriorating environment for journalists nationwide, especially after Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014 and state governments run by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) set the tone.

The AAP, itself a target of raids and cases and whose leader Arvind Kejriwal has spoken about (here and here) the union government’s attitude to press freedom, appears to be following the same model in Punjab, which it has governed since 2022.

A 2020 report by the Free Speech Collective, an analysis of arrests, detentions, summons, interrogations and show-cause notices against journalists between 2010 and 2020, documents 154 such cases, including 67 in 2020 alone: 73 cases, or 48% of the total, were reported from BJP-ruled states, Uttar Pradesh leading the pack with 29. Another 30 were from states ruled by the BJP with allies.

‘Blatant Attack On Freedom Of Press’

The 30-year-old Sikh separatist Amritpal Singh and his associates were named in four criminal cases involving allegations of spreading disharmony among classes, attempted murder, attacking police personnel and obstructing the lawful discharge of duty by public servants.

A manhunt that began on 18 March 2023 to find Amritpal Singh and members of his outfit Waris Punjab De (Heirs of Punjab) saw widespread suspension of internet and SMS services across the state.

In most districts, the suspension was lifted after a few days, but in Ferozepur, Moga, Sangrur, Taran Taran, in the Ajnala subdivision of Amritsar, and in some parts of Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar, it remained suspended till 23 March.

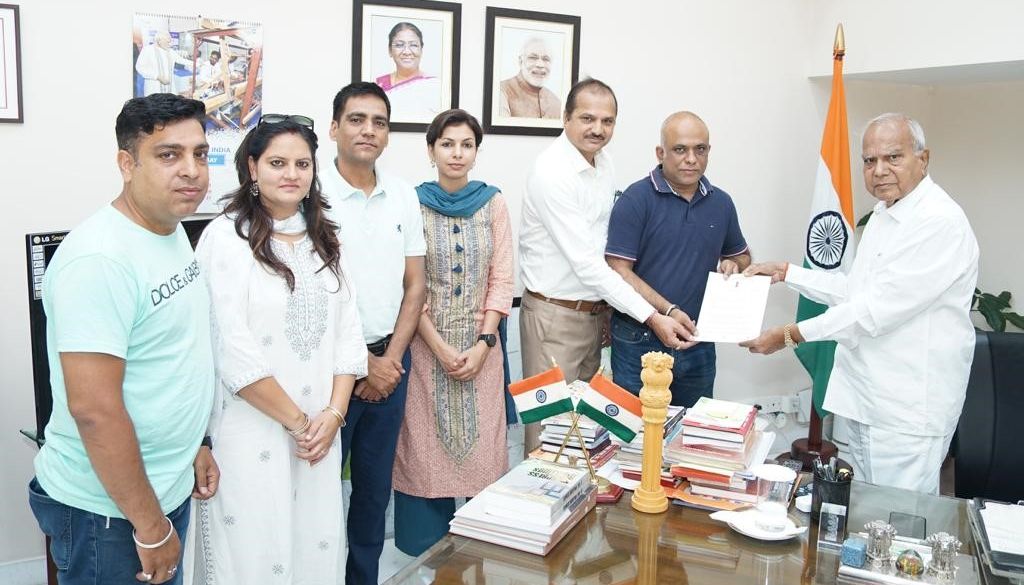

In a memorandum to Punjab governor Banwarilal Purohit on 19 May, members of the Chandigarh Press Club’s governing council called attention to the attacks on press freedom and free speech, citing the “arbitrary suspension” of Twitter handles of journalists and media organisations, police raids at journalists’ homes and the arrests of some independent journalists.

“This is a blatant attack on the freedom of press and free speech,” the Chandigarh Press Club said.

Harjeshwar Pal Singh, an assistant professor of history at Sri Guru Gobind Singh College, Chandigarh, told Article 14 that the curtailment of press freedom has worsened since the AAP came to power.

Harjeshwar Pal Singh said that the government has on one hand unleashed “an unprecedented propaganda” through social media, newspapers, advertisements and billboards while on the other hand it has throttled independent media.

“India is going down the ladder of the press freedom index… and this year it ranked even below Pakistan and Afghanistan,” said the assistant professor, calling the situation of press freedom in the country one of grave concern. “Such actions against media houses and journalists are not good for the health of a democracy because an independent media is a prerequisite for the free expression of people’s voice and issues,” he said.

The recent attacks on press freedoms in Punjab are set against India’s declining rank on the World Press Freedom Index compiled by global media watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF). India’s rank dropped 11 places in just a year to 161 of 180 countries in 2023, and 39 places from 2010, when it was ranked 122 of 178 countries.

Article 14 has extensively reported how perilous the environment for press freedom has become in general and for independent journalists in particular (here, here, here, here , here and here), as the State deploys a variety of laws, including those meant to prevent terrorism.

Most recently, on 3 October, the special cell of Delhi police raided the houses of around 46 journalists, contributors and writers linked to NewsClick, an online news portal, over allegations that the company received funds illegally from China, routed via the United States. Founder-editor of NewsClick Prabir Purkayastha and human resources head Amit Chakravarty were arrested and charged under the anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967.

Since 2018, there have been at least 44 summons, raids or notices to media companies and journalists by investigative agencies controlled by the union government, Newslaundry, an independent website (itself raided in 2021) reported in May 2023.

Early Morning Raids, Summons To Police Stations

Journalist Harsharan Kaur, who runs The Khalas TV, a YouTube channel with over 1 million subscribers, said her parents’ home in Chhapianwali village of Mansa district was raided by the Punjab police around 5:30 am on 24 March.

She was not at home. “They asked my family members about my whereabouts,” she said, “and told them to tell me to appear at the police station.”

Sukhpal Singh Khaira, member of the legislative assembly (MLA) from Bholath in Punjab’s Doaba region condemned the attack on media freedoms in the context of the raid at Harsharan Kaur’s house. In a tweet, Khaira tagged Punjab chief minister Bhagwant Mann and asked, “Is this badlav (change) you promised?”

The Punjab police visited the home of Jagjit Singh Panjoli, a correspondent for digital news portal The Unmute, in Panjoli Kalan village of Fatehgarh Sahib. Panjoli told Article 14 he was in Chandigarh on 24 March when the police team visited and asked his family members for details including a passport sized photograph of him and a copy of his Aadhaar card.

Rattandeep Singh Dhaliwal, Jasvir Singh and Ranbir Singh Rana were some other journalists whose houses were raided by the police.

“A few police personnel raided my house citing my contact with one of Amritpal’s aides as I was in touch with him for arranging an interview,” said Dhaliwal, the chief executive officer of Talk with Rattan, a platform discussing issues specific to the state of Punjab. The police personnel asked some “odd questions”, he remembered, such as where he was married, his parents-in-law’s profession, and how much land he owned.

A journalist who is also pursuing a doctorate at the Guru Nanak Dev University in Amritsar, Juzar Singh, was summoned by police three times. “I visited the police station twice, and the third time I refused to visit,” Juzar Singh told Article 14. He said policemen told him not to post anything related to Amritpal and what was happening in Punjab at the time on social media.

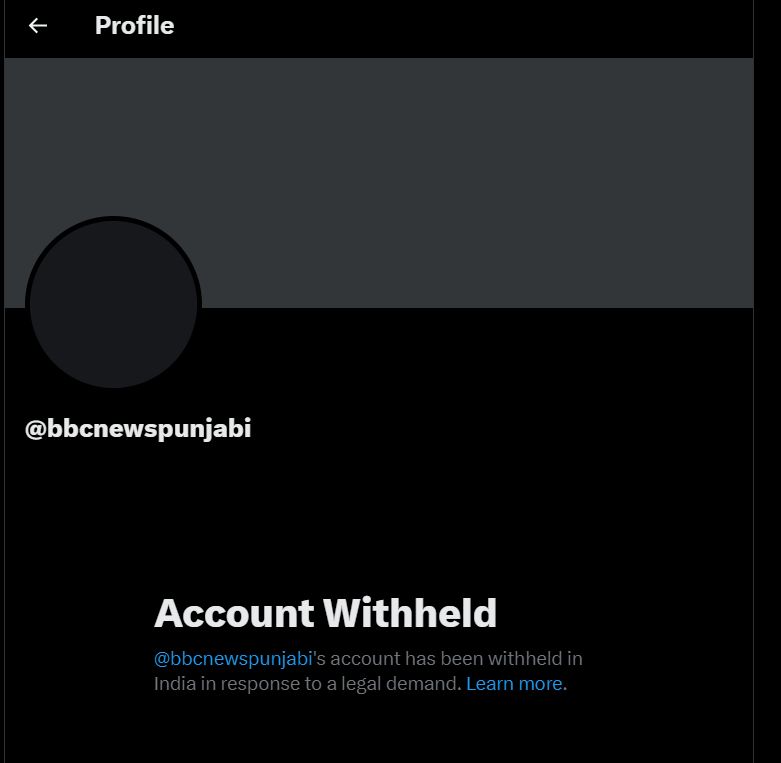

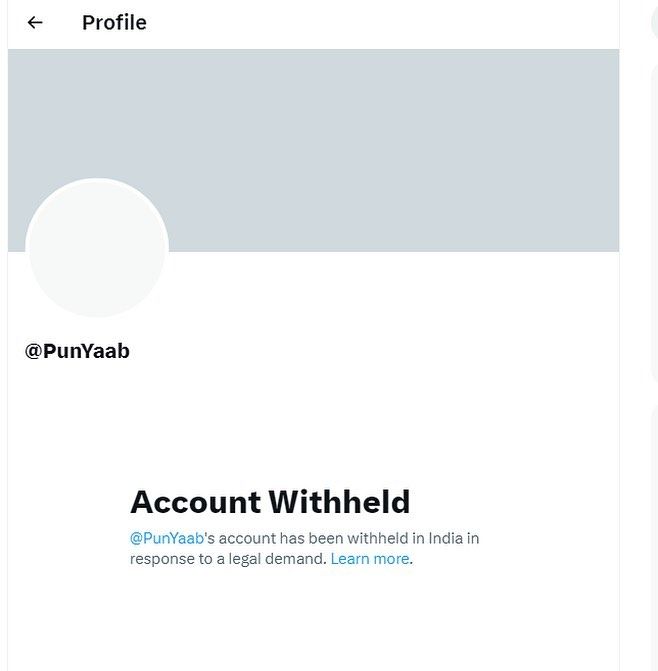

Social Media Accounts Withheld

Apart from raids, the government also blockaded social media accounts of some journalists who were covering developments around Amritpal Singh.

Journalists who found their social media accounts blocked included Kamaldeep Singh Brar, a senior journalist of the Indian Express in Amritsar; independent journalist Sandeep Singh; and Pro Punjab TV’s Chandigarh bureau head Gagandeep Singh.

Gazi’s handle on X, formerly Twitter, was blocked too.

Jagdeep Singh from Punjabi Lok channel, a well-known face in Punjab’s media circles, found his Facebook page blocked.

None of these journalists received any notification from the government specifying the reason for blocking their accounts. The Twitter account of BBC Punjabi was also temporarily withheld, though it was restored later in the day.

Sandeep Singh, a National Foundation for India (NFI) fellow in 2021, said they did not receive any reasoning from the platforms regarding why their accounts were suspended.

He said his Twitter handle stayed blocked for two months. “Even now, they have put a shadowban on my Twitter handle, as you cannot find my account in its people section when you type my handle’s tag in its search bar,” Sandeep Singh added.

Most journalists’ Twitter handles that were blocked amidst the Punjab police’s crackdown on Amritpal SIngh were unblocked two months later. Some, like Gazi, said their Twitter handle was blocked again in September along with that of his portal Sikh Siyasat.

Not only journalists’ social media handles but those of media organisations were blocked too, including prominent Punjabi channel Punjabi Lok. The Facebook page of this channel with over a million followers was blocked without any notice. The Facebook page of Samrath Awaaz was also blocked.

As a result of these actions, many local media organisations began to avoid publishing contentious reports out of fear of losing their primary source of income.

Amanpreet Singh Garhi of Samrath Awaaz, a local media channel, said the ban on their Facebook page played a major role in weakening their financial position. Garhi said, “Since my channel’s previous Facebook page was banned, I was not able to receive any payments pending from its monetisation.”

No Period In History Without Censorship

Jagtar Singh, a veteran journalist and author, told Article 14, “Governments have always used censorship from time to time.”

Shiv Inder Singh, editor-in-chief of Suhi Saver, an online Punjabi media portal, said attacks on press freedom have occurred in every period in the state. Around the 19th century, he said, newspapers of the region wrote critically about the administration and policies of the colonial rulers and faced retaliation from them, while post-independence media tended to align with one political party or another, sometimes different parties at different times.

“During the period of militancy in Punjab, there was a division in the regional media—one group promoted the State narrative where the other group promoted the separatist tendencies,” Shiv Inder Singh said. “As a result, both groups faced retaliation by political bosses.”

Sumit Singh, then editor of a magazine named Preet Lari that advocated Hindu-Sikh unity, was killed by a group of extremists during the insurgency in Punjab which began in the 1980s .

Journalists’ families also faced attacks. Two journalists, Jagdish Khanna and Sat Baghi, each lost a son because of their news reports. Ramesh Chandra, editor of Hind Samachar Group and a strong critic of extremists, was shot 64 times in broad daylight on 12 May 1984 in a busy market square in Jalandhar.

His father Lala Jagat Narian, who was the founder of Hind Samachar Group and a strong critic of the Khalistan movement, had been shot dead in September 1981.

Giani Jagjit Singh of Akali Patrika, and Sukhraj Singh, editor of Chingari, were some other journalists who were gunned down by extremists during the insurgency.

Shiv Inder Singh added that the trend of partisanship within the media has continued in Punjab. “Even in contemporary times many journalists are not setting any example in the field, and are getting aligned to a particular ideology.”

‘Cease The Suppression Of Critical Voices’

Associations of journalists came out in support of those who faced a blockade of their social media handles in 2023. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the world’s largest federation of journalists, said government censorship, the internet blackouts and restriction of journalists’ social media accounts were “dire impositions” on press freedom and democracy in India.

The Editors Guild of India (EGI) urged the state and central governments as well as the union ministry of electronics and information technology (MeitY) to act with restraint in such cases and to follow processes laid down by the Supreme Court of India (SC). The EGI further stated that the Supreme Court had expressly directed that all reasonable efforts be made to identify and notify those whose information is sought to be blocked before access is restricted, as well as a right to appeal. “No such process seems to have been followed in any of these shutdowns,” the EGI statement continued.

The Chandigarh Press Club also condemned the suspension of social media handles of many Punjab-based journalists during the manhunt for Amritpal Singh.

Article 14 tried to contact the Punjab government’s director of information and public relations Bhupinder Singh, but he did not respond to phone calls.

Advertisements Stopped: Ajit Group Editor-In-Chief

The AAP government in Punjab has also faced accusations of halting government advertisements to newspapers. On 4 March 2023, Barjinder Singh Hamdard, editor-in-chief of the Ajit group of publications, wrote to the Governor of Punjab alleging vendetta by the Mann-led AAP government against his organisation.

In the letter, he said the state government had stopped all government advertisements to his group and had issued threats to him through police officials. He added that his staffers had not been allowed to enter the state legislature building during the budget session.

Later, in the month of May, Hamdard was summoned by the Punjab Vigilance Bureau for questioning in a probe related to the Rs 315-crore Jang-e-Azadi museum in Kartarpur, Jalandhar, to which he had been appointed as member secretary by the previous Parkash Singh Badal-led Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) regime. He had played an instrumental role in its construction.

The entire opposition of the state—the SAD, Congress, BJP, Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Lok Insaf Party—came together to protest the probe initiated against Hamdard.

Television Journalist Arrested

In May, another journalist, Bhawna Kishore, a reporter with Times Now was arrested in a case related to an accident that occurred while she was travelling on assignment in Ludhiana to cover the inauguration of the AAP’s mohalla clinics by Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal and Mann.

The complainant, a woman who was injured when Kishore’s car collided with her, alleged that Kishore and her two colleagues entered into an altercation with her and used casteist slurs.

The trio were booked under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, and sections 279 (rash driving), 337 (hurting any person by acting rashly or negligently as to endanger human life) and 427 (commits mischief and thereby causes loss or damage) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860.

This action by the AAP government came after a Times Now report revealed that Kejriwal’s official bungalow had been renovated at a cost of almost Rs 45 crore. On 10 May, the three journalists were granted bail by the Punjab and Haryana high court.

Press bodies came out in support of Kishore, calling it an attack on press freedom. The Chandigarh Press Club in its statement asked why passengers in the car were booked.

“How would one know the caste of the complainant to use derogatory language against their caste?” said the statement, which urged the governor to ensure there was no further intimation. “Who among the three used such language to be specific?”

(Ritish Pandit is an independent journalist based in Chandigarh.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.