Hyderabad: Gaurav Bhoi couldn’t believe his ears when he heard about the development that morning.

It was around 5:30 am on 25 February 2023, the time when Sitaram Bagh, the munshi or manager, usually woke up workers at VBI Bricks on the outskirts of Hyderabad, so they could finish their morning chores and get to work.

Unlike other days, however, Gaurav Bhoi had been woken up by a commotion, and found that none of his three siblings and pathri (unit of brick moulders) members were in the room. Confused, he rushed out of the hovel, only to hear Bagh tell someone on the phone, “Navin’s parents have run away with four others—they are nowhere to be found.”

Gaurav Bhoi, 22, from Ainlabhata village in western Odisha’s Bolangir district, was baffled. Navin was not a regular worker at the kiln, but had been helping his parents and cousin mould bricks for about a month. A day earlier, he had bid goodbye to everyone, saying he was headed to Chennai, where he worked as a security guard.

Now, six people—Navin’s mother, father, cousin, her 10-year-old son and two other workers—were missing, and everyone was at a loss about how and where they had gone.

D Venkateswarlu, the owner of VBI Bricks, was livid.

“I knew immediately that this was pre-planned. That boy asked me for Rs 10,000 before he left, saying he was going to get married soon,” he told Article 14 during an interview in May 2023. He said Navin had organised a car to arrive in the dead of night, around 1:30 am, to pick up the workers.

Instances when workers escaped from brick kilns in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana were rare, but not unheard of, especially in recent years. They were fuelled by a desire to escape the highly exploitative conditions at worksites, Article 14 found during a nine-month long investigation into modern slavery and labour trafficking.

Working hours in brick kilns spanned anywhere between 12 hours to 17 hours a day, up from eight-10 hours until the late 1980s. The increased workload was largely due to mechanisation of parts of the production process such as preparing the clay for moulding bricks and hauling unbaked bricks to the firing area, which also reduced the manpower requirement in brick kilns.

Workers depended on a variety of supplements to get through such long hours, such as paracetamol tablets, pain-killers, other habit-forming drugs and, increasingly, injections. These were supplied or administered readily and onsite by medical practitioners who were on the payroll of kiln owners. The same unqualified practitioners treated the workers when they had a fever, diarrhoea or other illness.

There were frequent accidents on site, including some that left workers dead or impaired or traumatised for life. Workers suffered from high morbidity and bodily depletion and stopped working in kilns once they reached their 50s, when they found the work too strenuous.

Many workers wished to flee from worksites, especially when the targets were too steep or there were medical emergencies. But only a few of them dared to take the risk, and a handful among them—mostly young men like Navin who were exposed to the world beyond their villages and brick kilns—successfully executed their plan.

Most plans, however, ended in failure, as kiln owners used multiple channels of surveillance to track down and bring back workers. Navin’s plan was no exception.

The last of a four-part series on the persistence of modern slavery in India, this report investigates the long-term impact of trafficking on survivors, their health and their freedom. Part 1 explored the magnitude of distress in rural western Odisha that prompted growing numbers of poor to seek out work as bonded labourers despite a 47-year-old law abolishing the practice; Part 2 probed the organised networks of traffickers and kiln owners; while Part 3 considered the various violations of laws and rights in keeping modern slavery alive in India.

Mechanisation, Real Estate Boom Heighten Exploitation

In industry parlance, VBI Bricks was a mid-sized kiln that employed 50-100 workers; small kilns had fewer than than 50 workers, whereas kilns with over 100 workers were considered large.

In 2022-23, the number of workers at the kiln hovered around 80. More than 70% of them were migrants from Odisha who lived on site and were engaged on a piece-rate basis. They included 42 moulders grouped into 12 pathris and 20 dulai walas (haulage workers). The remaining workers including three drivers, three jalai walas (those who fired up the furnaces) and a few loaders were all locals who were paid monthly wages.

Some owners engaged workers from Chhattisgarh as moulders and haulage workers, but Venkateswarlu, like most other owners, preferred Odia workers for their industriousness.

“They are docile and keep to themselves and their work, whereas the Chhattisgarhis talk amongst themselves and waste a lot of time. They also tend to run away a lot,” he said.

For moulders and dulai workers, the daily schedule was gruelling, with little time even for sleep. Sitaram Bagh roused them at the crack of dawn, before 6:00 am in the winter months, and at or before 5:00 am during the summers. He gave them an hour to freshen up, relieve themselves, and eat their breakfast—mostly rice from the previous night soaked in water and eaten with salt, chillies and onion—before reporting for work.

Haulage workers mostly toiled through the day and were relieved by evening, whereas moulders worked in two shifts. The morning shift lasted around six hours, and was followed by a lunch break—two hours in the winters and four-five hours in the summers, so as to avoid the intense midday heat.

Men usually took a siesta at this time, but women were preoccupied with cooking and other domestic chores. The second shift lasted another five-six hours, or longer—the site was equipped with floodlights, so that work could continue late into the night.

“All of us are young, so we don’t face any problem. But older people struggle to get through the day,” said Gaurav Bhoi.

Those who started working in brick kilns in the 1980s and 1990s said the workday then was much shorter, around eight-10 hours, and the work relatively less demanding. Typically, workers spent a few hours everyday mixing various raw materials manually to prepare the clay, and moulded or hauled bricks during the remaining time. They found some time to laze around or talk to other workers in the same kiln in the evenings, they said.

Two factors drove the increase in work hours and exploitation—mechanisation of parts of the production process in the late Nineties, and a real estate boom following the establishment of Telangana as a separate state in 2013-14.

The use of tractors for mixing raw materials constituted a major, sweeping change. It freed workers from the task, and enabled their deployment for moulding or hauling bricks for the entire time. In some cases, especially in big kilns, cranes were used to transport unbaked bricks to the firing area, which reduced the requirement for haulage workers by up to 30%. Some haulage workers were still required to stack bricks into furnaces.

These changes enabled kiln owners to cash in on the real estate boom in the post-liberalisation years and then again after the creation of Telangana in 2014.

Several new districts were created in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana during this period, and Amravati was proposed as the new capital of Andhra Pradesh. Both states also eased regulations and requirements for setting up new industries and businesses. This set forth a flurry of construction activity, for government offices, markets and malls, public amenities and private residences.

Barring premium projects that used light-weight bricks made of fly ash, all others depended on mud bricks.

Exacting Work Routine, Scanty Nutrition

Once the day commenced at VBI Bricks, all that could be heard was the clanking of moulds against the earth and the piling of unbaked bricks on the furnace floor.

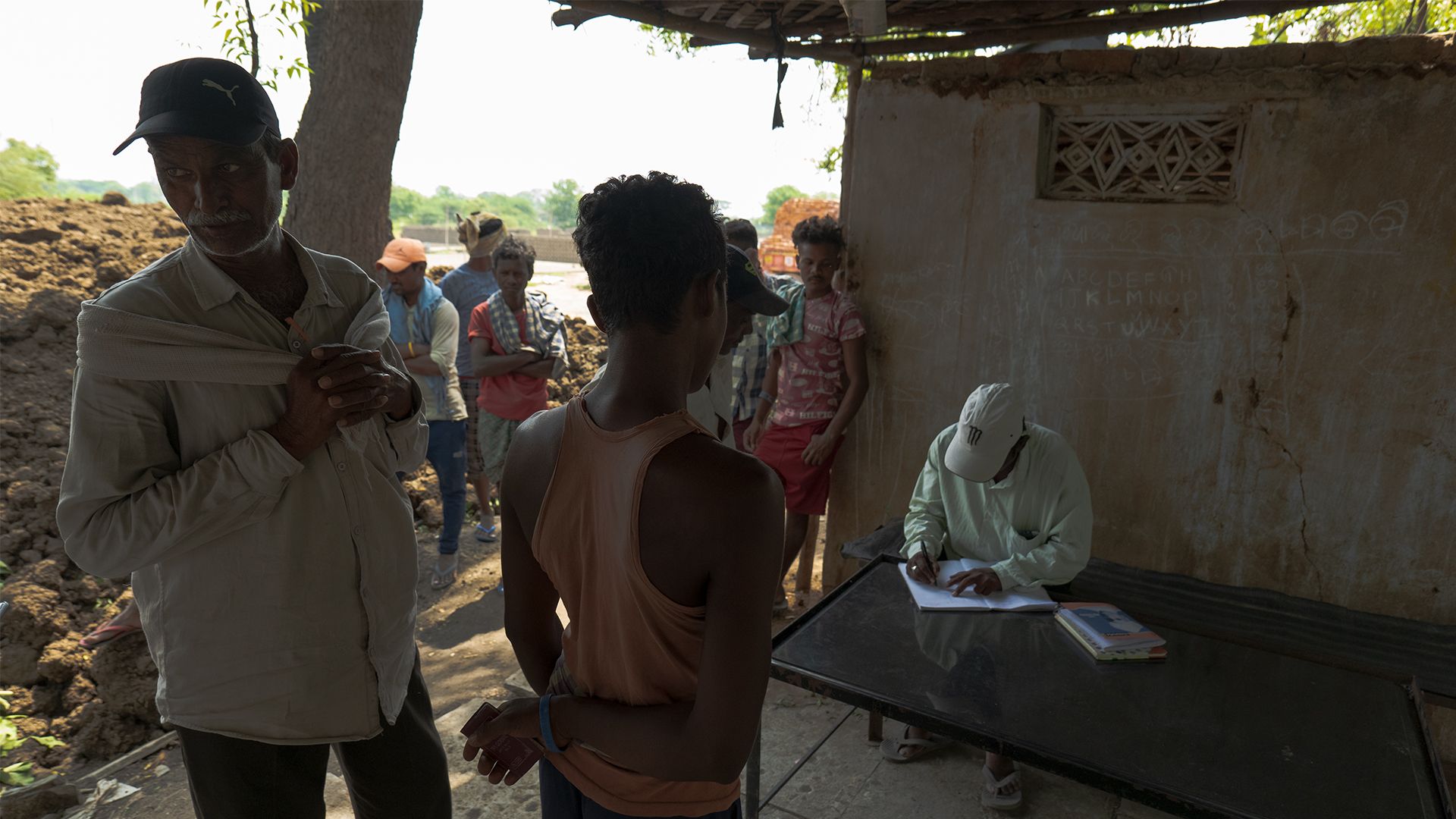

The munshi, Bagh, usually stood near the line of dulai workers ferrying bricks from the drying area to the furnace—women carried 10 bricks on their head, whereas men carried 12 bricks on their shoulders at a time, strung on bamboo poles. He handed out a token to these workers for every 10/12 bricks stacked in the furnace, and collected them at the end of the week, after recording the figure in a register and on small notepads kept with workers, usually the male head of the family.

Bagh and Venkateswarlu, who mostly lived onsite, also maintained a close watch over pathris and scolded them if they conversed among themselves or were missing for more than a few minutes.

The Bhois, like all other pathris, worked in close coordination. One of the brothers fetched clay for moulding bricks from the mixing pit and readied brick-sized balls; another stuffed these into moulds, ensuring there were no gaps, while the third brother carried these moulds to the drying area, emptied the moulds and brought them back. Bhagyawati joined the third brother as and when she completed domestic chores. She also helped them flip the wet bricks from time to time and arrange them in neat stacks once they dried. Chitrasen Bhoi had a small notepad in which Bagh recorded their weekly production, always above the weekly crop of 20,000 bricks expected per pathri, and also always more than what other pathris produced at the kiln.

It was easy to tell that all the pathris were Odia from their typical style of work. The workers who stuffed clay into moulds stood inside squarish, waist-deep pits and used the ground as a table, whereas moulders from Chhattisgarh and other states sat on the ground and crouched over to mould bricks.

“I don’t know why, but it has always been like this,” Gaurav Bhoi told Article 14 in his characteristic monotone while standing in the pit and stuffing clay into a mould. “It is good though, because you don’t need to bend over or hurt your back while setting the brick,” he said, clanking the mould several times on the ground in demonstration.

Nevertheless, moulding or loading bricks for hours on end was exhausting, and nearly all workers suffered from aches and pains in their back, waist, and joints. Their dietary intake, on the other hand, was far from what was required for such labour.

Once a week, after Sitaram or Venkateswarlu handed out the weekly food allowance for Rs 500 per pathri, the brothers went to the market to buy groceries and vegetables. Bhagyawati, like all other women, stayed back at the kiln and chopped firewood for cooking their meals for the entire week. For breakfast, lunch as well as dinner, the Bhois had rice, a curry with lots of potatoes and some other vegetables and, occasionally, dal, all cooked by Bhagyawati. They rarely ate eggs or meat, and never had milk or other dairy products.

Doctors: Quacks With Injections, Intravenous Drips

All the moulders and haulage workers at VBI Bricks depended on two doctors who had clinics in Adibatla, a neighbouring village located 6 km away. They visited either of these clinics for any health problems, always carrying the notebook reserved for each doctor at the kiln.

Abdul Rahman and Sheikh Muzeeb, the two doctors, provided them pills, injections and intravenous drips free of cost. They entered the worker’s name, date and charges for treatment in the notebook, and were paid by the kiln owner from time to time. In rare cases, they referred workers to private hospitals.

The Bhoi siblings, however, made it a point to take off from work and visit the government hospital in Nampally, 25 km away, whenever they fell sick.

The first time was only a few days after their arrival, in mid-December 2022. Chitrasen Bhoi developed a high fever, cold and a severe body ache. It was the change of climate and water, said Venkateswarlu. Four to five workers at VBI Bricks fell sick every day during this period.

The Bhois had to visit the hospital on two more occasions.

On each of these occasions, the Bhois had to seek the owner’s permission, and were accompanied by a driver from the kiln.

“The doctors here are not good, so we don’t go to them,” said Chitrasen Bhoi. “We never take any pills or injections from them also.”

His apprehensions were well-founded. Like most doctors who treated brick kiln workers in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, neither Muzeeb nor Rahman had a degree in medicine or registration to practise as a doctor. They were registered medical practitioners (RMPs, also called rural medical practitioners) and private medical practitioners (PMPs), trained to be assistants or compounders to registered doctors.

“Most of us are science graduates who worked as operation theatre or laboratory assistants,” said one PMP in Warangal, about 150 km north-east of Hyderabad. “Those who started practising before the 1990s were registered as RMPs and those like me who joined later are called PMPs.”

In many parts of the country, including in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, RMPs have long demanded recognition to practise as doctors, but in the medical fraternity and by law, they were designated akin to quacks.

Kiln workers, on the other hand, suffered from a range of complex health problems, activists and doctors told Article 14. These included diarrhoea, skin allergies, tuberculosis, respiratory tract infections, throat infections, kidney problems, menstrual infections and gastroenterological problems.

Whatever the patient’s complaint, quacks treated the workers and also administered drugs with deadly side-effects that enabled workers to put in prolonged hours without a break. Some of them spoke to Article 14 on condition of anonymity and explained how they worked, and what medicines they provided.

The RMPs and PMPs had a standard rate for kiln workers, starting at Rs 100 to 150 for an injection and a few pills. Each RMP or PMP in the region catered to seven to 10 brick kilns, visiting the kilns on motorbikes once every day or when there were emergencies, carrying a large bag with a stethoscope, blood pressure monitor, and a wide range of pills and injections. One RMP told Article 14 he had medical drugs worth Rs 1 lakh in his bag.

Rarely, like in the case of VBI Bricks, workers visited the RMPs and PMPs at their clinic.

“Workers complain a lot about body ache, and want pain relievers all the time,” Prasad, one such PMP in Warangal, told Article 14 while examining patients at a kiln. He enlisted the composition of various medicines he and other RMPs provided to workers regularly.

They included etoricoxib + paracetamol which blocked the release of certain chemical messengers in the brain that caused pain and fever; aceclofenac + paracetamol, which blocked the action of chemical messengers responsible for pain, fever and inflammation; and diclofenac + paracetamol, which relieved pain due to migraine, muscle pain, rheumatoid arthritis, spondylitis and painful menses.

The listed side effects of these drugs included nausea, diarrhea, flatulence, vertigo, decreased appetite, increased liver enzymes and indigestion.

“Among women, there is a lot of demand for pills to delay their periods so they can work without any problems,” continued Prasad. He said many young women also asked for contraceptive pills or pills for abortion, but always without the knowledge of their families.

In recent years, injections had replaced pills as the preferred mode of treatment as they yielded quicker results. Some workers who had worked in Telangana’s Peddapalli and Karimnagar districts told Article 14 they had been administered injections on the go, while they were at loading or moulding bricks.

Venkateswarlu, however, claimed VBI Bricks did not follow such inhuman practices. “For injections and drips, I always send workers to the doctor, and let them rest for a few hours after they come back,” he said.

Decay And Death As Collateral Damage

The gruelling schedule in the brick kilns took a heavy toll on workers. Accidents were frequent, some of them fatal, some resulting in lifelong impairment.

In 2015-16, researchers G Vijay and Tathagata Sengupta surveyed nearly 200 Odia workers engaged in Telangana’s Rangareddy district, where VBI Bricks was also located. They found that on average, every worker faced 14 minor accidents in a season, and a few workers died every season due to electrocution, as electricity connections at most kilns were illegal.

Deaths were also common in April and May, when maximum temperatures soared above 40 degrees Celsius, Sengupta and several others including kiln workers, owners and munshis told Article 14.

Many workers experienced sudden blackouts, most likely because they were malnourished but also due to over-exhaustion in the summer heat. “The workers are like fish,” remarked Venkateswarlu. “They suddenly lose consciousness.”

Treatment, on most such occasions, comprised glucose drips and injections from the RMPs or PMPs. Only some workers were sent to private hospitals when they turned serious, and a few lost their lives. Owners compensated families of the deceased with a few thousand rupees, but did not intimate the police or government authorities about the deaths.

On the other hand, all those who had worked for a few years in brick kilns told Article 14 that the “kamjori” (weakness) never left them, not even when they returned to their villages in Odisha. They also complained of sudden, inexplicable illnesses and death, especially among older workers.

In a book published in 2017, Vijay and Sengupta drew a direct link between high mortality rates among working age adults in Bolangir and seasonal work in brick kilns. They said the crude death rate figures, highest for Bolangir among all Odisha districts, could be “a consequence of the morbidity and bodily depletion that these workers suffer during the course of this tenuous employment”.

Industry On Its Deathbed, Claim Kiln Owners

Venkateswarlu rarely smiled when Article 14 visited the worksite, but he broke out into a wide grin when asked about his best profits.

“After the formation of Telangana, there was a boom in the real estate market, and all of us (owners) made money,” the owner of VBI Bricks said. “But in 2018, we reaped bumper profits due to a two-week truck strike.”

In July 2018, over 6 lakh trucks went off the roads in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana as part of a nationwide truckers’ stir. With transportation of bricks from kilns to customers affected, the ensuing backlogs pushed prices upwards by nearly 50%.

In Hyderabad, owners reported selling bricks at Rs 9 per unit compared to the usual Rs 6; whereas in Karimnagar and Peddapalli districts of Telangana, owners reported selling bricks at Rs 12-14 per unit, up from the usual Rs 8-9.

The Covid-19 pandemic, however, broke the spell of profits. Brick kilns continued operations through the lockdowns as they were exempted from various restrictions by the ministry of home affairs, but the construction industry had stalled, and the demand for bricks was down to a trickle. Owners still holding large unsold stocks had to seek fresh credit for another production cycle.

“The business is no longer profitable,” claimed Venkateswarlu. “But I cannot quit because I have taken Rs 70 lakh on loan, which can’t be repaid even if I sell all my property.” Keeping the kiln running was his only option.

Owners of small kilns (fewer than 50 workers) told Article 14 that loans accounted for nearly 100% of their seasonal investment, while for mid-sized kiln (50-100 workers) owners such as Venkateswarlu, 50% of the investment came from loans, and the rest from the sale of bricks produced in the previous season.

Only owners of large kilns (over 100 workers) were less exposed to loans, having as they did connections in the construction industry, which offset their risks.

Regardless of the size of their operations, owners said the business was highly risky and the only way to repay debts was by remaining in the trade, taking fresh loans for another season, and hoping for the best.

“I invested over Rs 2.5 crore this year, but I don’t know if I will make any profit,” said K Suresh, the owner of BBI Bricks in Peddapalli district, where more than 150 workers were engaged in producing 60 lakh bricks during the 2022-23 season. A lot depended on the market and weather, he said.

“I don’t even know for sure how much I will earn from this year’s production until all the bricks are sold, which will take at least two-three years,” he added.

Kiln owners also said the industry would close down soon as demand for mud bricks fell in favour of modern construction technology.

Rajender Reddy, president of the Telangana Brick Kiln Employers’ Welfare Association, said premium customers had already switched to fly ash bricks that are lightweight. “Many builders and government projects are also making walls from concrete using Japanese technology,” Reddy said. “As a result, the demand for our bricks has come down sharply and brick kilns may become extinct in a few years’ time.”

Newer Kiln Operators Say Margins Down, But Improving

Though a majority of kiln owners predicted an imminent closure of the industry, Article 14 met more than 10 others in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana who entered the business in the post-pandemic period and said profits were decent enough to prompt them to seek more credit to expand the business.

Each had taken loans totalling Rs 8 lakh - Rs 15 lakh and had leased land at steep prices on the outskirts of big cities.

“Before me, no one in my family had anything to do with brick kilns,” said one owner in his mid-20s, who operated a kiln in Nakalpalli village on the outskirts of Warangal.

The young owner’s parents were both farmers, and he completed college and worked as an office assistant, only to be rendered jobless by the pandemic. In 2021, encouraged by friends and acquaintances, he took Rs 10 lakh on loan to start his kiln, and employed 30 workers.

Still understanding the business and tying up a supply chain, the owner said, “But I managed to make a profit in the first two years, and engaged 50 workers this year.”

During an average year, profits hovered around 20%-25%, he and other owners said, touching 50% in a good year such as 2018. These rates were subsequently corroborated by several other kiln owners in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

“No doubt, the profit margins were much higher around 10 years ago. But it’s not as if we are losing money now,” said Koteshwar Rao, who has been running BKR Bricks for more than 30 years.

All the owners in Warangal said they hoped to scale up production in ensuing years as the demand for mud-bricks was still high, especially among low-cost and medium budget users.

Moneylenders who extended credit to kiln owners also attested that the mud-brick industry was thriving.

“Around eight-10 kiln owners are my regular clients, and their borrowings comprise nearly 30% of my business,” said one moneylender in Anakapalli district of Andhra Pradesh. “If there was any doubt about the profitability of brick kilns, I would not expose myself to a single owner.”

Untimely Showers Wash Away Fruit Of Their Labour

The Bhois paid scant attention to these minutiae, focused as they were on their targets for the season. They wanted to mould at least 400,000 bricks, so they could earn Rs 320,000, at the rate of Rs 800 per 1,000 bricks.

They remained ahead of all the other pathris throughout the season, moulding at least 20,000 bricks every week, and hoping to achieve their target by the first week of May and return home.

In the third week of April 2023, however, heavy rains dissolved 30,000 of their bricks. This was despite their painstaking care for their unbaked goods, two layers of tarpaulin sheets carefully secured with bricks to ensure the wind did not whip the protective layers away.

In all, untimely rain in late April damaged around 600,000 bricks at the kiln, including those being baked in furnaces doused by the rain. It also prolonged the production season by a few weeks, so as to compensate for the losses.

The pressure fell squarely on the moulders, who were now pushed to produce more than the earlier target of 20,000 bricks per week.

Still, the Bhois faced no problem.

Unlike other pathris, they rarely worked late into the night but by the first week of May, had completed 320,000 bricks excluding those damaged in the rain. Their closest competitors in the kiln had made 280,000.

Even the owner was happy, and paid a part of the wages due to them into the account of their father Saranga Bhoi. The money was immediately directed towards the construction of an additional room, a lavatory and a bathroom in their house, in preparation for Chitrasen’s wedding later in the year.

Meanwhile, Chitrasen spent hours on the phone with the girl he was slated to marry, and resolved to sink a borewell in the house so that she could have the luxury of tapped water.

Gaurav Bhoi agreed wholeheartedly. Sinking a borewell entailed an expense of at least Rs 60,000. The brothers thought about how to make arrangements for that cash.

For Those Who Seek Freedom, Quick Reprisal

Workers largely endured the prevailing conditions in brick kilns silently, but also nursed the urge to flee, especially when the work was too demanding or they had medical emergencies back in the village.

Navin’s parents, who fled from VBI Bricks with his cousin, her son and two other moulders in the wee hours of 25 February, were both above 40 years of age. They found it difficult to meet the steep production targets set by the owner, said Navin, who met Article 14 later and conceded to hatching and executing the plan for their escape with a friend from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh.

Navin said he received his parents and others the next morning on the outskirts of Vijayawada. They took shelter in a vacant apartment arranged by his friend, and hoped to stay there for some time—returning to their village in Odisha’s Nuapada district would lead to the sardar forcing them to repay the advance.

Meanwhile, Venkateswarlu responded like any other owner faced with workers on the run. He reached out to relatives, business partners, owners of factories and hotels near the kiln and officials in the local police in a bid to locate them and bring them back, said well-placed sources.

Soon, he accessed the CCTV footage of a neighbouring cement plant that showed a four-wheeler going from the kiln towards Nehru Ring Road around 1:30 am on the night of the jailbreak. Suspecting Navin’s hand behind the escapade and hearing that Navin was in or around Vijayawada, he intimated business owners there, providing them with a description of Navin and the workers.

A restaurant owner shared CCTV footage showing Navin buying food around 1:30 pm on 26 February.

Venkateswarlu and his brother-in-law left for Vijayawada in a car. Around 9 pm, when Navin visited the hotel again to buy dinner, they nabbed him and forced him to lead them to the apartment where the workers were holed up. All barring Navin were then brought back to the kiln by car.

Venkateswarlu conceded to Article 14 that he travelled to Vijayawada, and said he wanted to bring back Navin too, to counsel him.

“I was holding on to him after we reached the apartment, but his mother pleaded with me to let go, promising he would not run away. A little later, when we were leaving the apartment, he ran away,” he told Article 14, visibly bitter.

A few weeks later, another pathri ran away from VBI Bricks.

“Their relatives who worked in a factory nearby said they had gone to Bengaluru. So I went there and brought them back,” said Venkateswarlu, claiming that the workers themselves wanted to return and that he had not forced or assaulted them.

But those who had worked at his kiln earlier showed Article 14 a video showing the owner heckling and assaulting a middle-aged worker.

An Advance, A Promise, A Slave Season

In the last week of May 2023, when it looked like the Bhois would soon complete moulding their quota of 400,000 bricks at VBI Bricks on the southern fringes of Hyderabad, they took an audacious step.

Gaurav and Chitrasen Bhoi approached the owner Venkateswarlu, and told him they wanted to sink a borewell at their home in Ainlabhata village in Odisha’s Bolangir district. For this, they needed Rs 60,000 over and above their wages for the season, which would be computed in a few days.

Could he advance them this money on the condition that they would return to his kiln the next season, the brothers asked.

It was unusual for kiln workers to strike deals directly with owners. Sardars rarely sent workers to the same kiln more than once to pre-empt such possibilities.

The Bhois had, in fact, worked at VBI Bricks the previous year too, and the brothers had requested Venkateswarlu to intervene with their sardar so that they could work at his factory again.

Now, Gaurav and Chitrasen Bhoi were trying to build on this relationship. That they were the top moulders at the kiln worked in their favour, and the owner advanced them the money a few days later.

The payment of lump sum advances in lieu of services to be rendered in future, also called debt bondage, was outlawed in India by the BLSAA, 1976. Kiln owners Article 14 spoke to, however, defended the practice saying they were helping poor families who had no other means of employment during the lean agricultural season.

In reality, kiln owners reaped handsome profits, to the tune of 20% to 40%.

Gaurav Bhoi called his friends back home and told them when he was likely to reach Ainlabhata. He looked forward to nothing more than hanging out with his gang.

Chitrasen, on the other hand, looked forward to finally meeting his would-be wife, whom he had been speaking to for the past six months. Their wedding was scheduled to be held around Diwali in 2023, and there was much remaining to be done in the interim, including sinking a borewell at home.

Normally, poor couples in western Odisha migrated to brick kilns soon after their marriage. With an advance already taken from Venkateswarlu, would Chitrasen Bhoi also bring his wife along for the next season?

“I think so,” he said.

Bhagyawati will come along too, she said. “Who will cook for my brothers? Bhabhi (sister-in-law) used to live in a hostel, she cannot cook anything.”

(Aritra Bhattacharya is an independent journalist and researcher based in Kolkata. Saurabh Kumar is a researcher, multimedia journalist and documentary film-maker based in Mumbai.)

This is the last of a four-part series. Here is part 1, part 2 and part 3.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.