Jammu: On 18 July 2023, in a ramshackle shanty town in a neighbourhood called Kiryani Talab, Haseena Begum, a 62-year-old woman, was preparing breakfast for her five grandchildren when an unexpected visitor rushed into her modest dwelling. The young woman bore sombre news—some of Rohingya refugees had been baton-charged and tear-gassed within Kathua jail, 60 km southwest of Jammu.

Haseena Begum's immediate concern was the well-being of her son and daughter-in-law, who had been in detention since March 2021—among 271 Rohingya now detained at the Hiranagar holding centre in the Kathua jail, including 74 women and 70 children, many of whom were born within the confines of the centre.

After their parents’ arrest and detention, in violation of India’s own and other international laws, Haseena Begum’s five young children, aged five to 14, now have only one guardian, their grandmother, who also battles her deteriorating health.

“Someone will have to care for these children after I die,” she said.

There are about 32 children living without their parents in similar circumstances in Jammu, refugees we spoke to estimated.

The sequence of events leading up to this incident had been marked by clashes that erupted at Hiranagar. Rohingya refugees held there had launched a hunger strike to protest against their indefinite confinement, coinciding with the observance of Eid ul Adha on 29 June.

A Desperate Demand: Freedom Or Repatriation To Myanmar

Haseena Begum received a call from his son some days before Eid. “My son informed me that the jail authorities had kept them hungry for the past few days,” she said.

Their demand: release from captivity or repatriation to Myanmar.

That refugees would seek repatriation to Myanmar, their home country from which they had fled, indicated their desperation and reflected, said experts, the approach of the government of India to them as Muslims.

Koushal Kumar, Kathua district jail's superintendent and the holding centre's overseer, told The Wire that on 18 July refugees "tried to break open the gate and come out, but we closed the gate". As the jail plunged into chaos, a stone struck Kumar, exacerbating the situation and necessitating the intervention of both the police and paramilitary forces, who quelled the turmoil using baton charges and tear gas.

Tragedy struck in the aftermath. Refugees at Kiryani Talab alleged the death of a five-month-old infant called Umar Habiba due to the effects of tear gas within the holding centre. The parents, refugees said, were taken to her burial in handcuffs. Koushal Kumar denied that tear gas had led to the child's death. The child, he said, had been unwell and had died two days later.

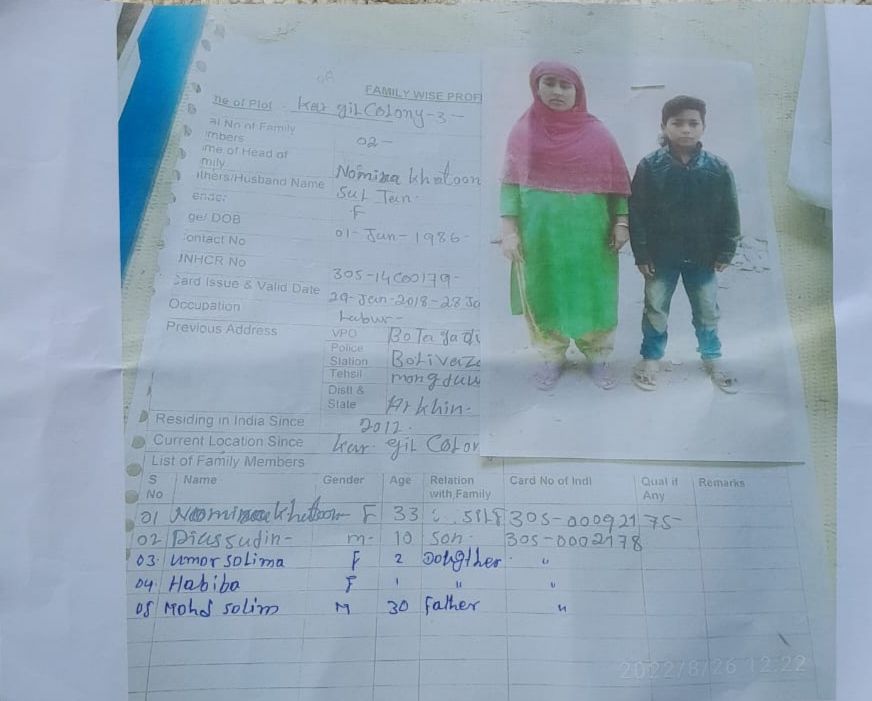

Umar Habiba’s father, Mohammed Saleem, 40, arrived in Jammu in 2012, only to find himself in detention the same year. He was detained when police checked if he had an identity card issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office in New Delhi. After his arrest he was kept in Amphalla jail of Jammu district. In March 2021, Saleem, his wife Numina and teenage son Riazuddin, were moved 60 km to the southeast to the Hiranagar sub-jail, after it was redesignated from a prison to a holding centre for Rohingya refugees.

The redesignation indicated the government’s intention of confining Rohingya for an indefinite period since they could not be legally in prison with no criminal cases or charges against them, said experts.

Government crackdowns on the Rohingya have recently escalated. On 24 July, six days after the Hiranagar episode, the anti-terrorism squad of the Uttar Pradesh police raided Rohingya settlements in various districts and arrested 74 Rohingya, including 10 juveniles.

According to an estimate made in March 2021 by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch, there are 40,000 Rohingya refugees in India, most of whom live in slums in Jammu, Hyderabad, and New Delhi. About 7,000 refugees live in shanty towns in Jammu, a Hindu-majority city. Kiryani Talab is the biggest of these settlements.

The UNHCR has documented about 17,000 Rohingya refugees in India, but many more are unregistered because of official hostility and the prospect of deportation.

India’s Growing Hostility

On 22 September 2022, the union government—refusing to provide documentation for a Rohingya woman and her children trying to join their father in the US—told the Delhi High Court that Rohingya refugees living in India “were seriously undermining the country’s national security”.

In 2018, claiming the Rohingya had links to “terror organisations”, the government of prime minister Narendra Modi told the Supreme Court, “The court has no business to interfere in such matters of what they call illegal immigrants or illegal migrants.”

With no evidence, television channels and media allied with the government have amplified allegations (here, here and here) that the Rohingya were linked to terrorism and were security threats.

This narrative has contributed, as many have observed, to the systematic criminalisation of the Rohingya, even as India says it will deport refugees as illegal immigrants who do not hold valid travel documents. Deportation, said legal experts, violates the international legal principle of non-refoulment, under which countries may not return refugees to countries where they face harm or persecution.

Since India is not a party to the United Nations (UN) Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) and its 1967 Protocol, its refugee protection obligations are limited, as lawyer Malvika Prasad wrote in Article 14 in February 2020.

But non-refoulement is regarded as established global law binding on all countries, and the Rohingya are recognised as asylum seekers and refugees by the UNHCR. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that Rohingya in India, too, were covered by this principle.

Article 21 of the Constitution ensures the right to life to non-citizens as well, but in April 2021 the right to life was not defended by the SupremeCourt, before whom the consequences of deporting the Rohingya were argued.

“Possibly, that is the fear that if they go back to Myanmar, they will be slaughtered,” said then Chief Justice S A Bobde. “But we cannot control all that… we are not called upon to condemn or condone genocide.”

India is also a party to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, the Child Rights Convention 1989, and various other instruments that make clear rights for detenus, especially women and children.

Instead, India appears to be violating both global and national laws, with even minors held, as lawyer Ujjaini Chatterji found—in this October 2022 account in Article 14, confirming our January 2022 story—at a detention centre called Sewa Kendra in the northwest Delhi suburb of Shahzada Bagh. Chatterji found refugees being held in violation of a slew of national and international laws, with no sunlight, no warm clothing, abusive officials, limited healthcare, forced labour and limited access to toilets.

Conditions within Hiranagar, said refugees, were similarly grim, leading to the revolt of 18 July 2023. Tensions have simmered within the holding centre since May 2021. The refugees had resorted to demonstrations and hunger strikes intermittently.

The Revolt In Hiranagar

Rohingya detainees reportedly took control of some jail offices in the Hiranagar holding centre and threw stones at officials on 18 July. This action prompted police intervention, resulting in clashes, leading to injuries to refugees, a senior police officer confirmed on condition of anonymity since he was not authorised to speak to the media.

Saber Kyaw Min, the director of Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, a group dedicated to the welfare of Rohingya refugees, expressed alarm at the violence inflicted upon the detained refugees. “The Rohingya Human Rights Initiative is deeply alarmed by the shootings and tear gas attacks on Rohingya refugees in Jammu," Min said in an email to Article 14. He called for an immediate end to “human rights violations” and “arbitrary detentions”.

Min said the Rohinga at Hiranagar were “unlawfully detained without any charges or FIRs (first information reports)”. He emphasised their vulnerable status. Many possessed identity cards validated by the UNHCR, he added.

A Word document shared by Min outlined instances of violence and deprivation within the holding centre. Over a month, detenus claimed to have suffered beatings at the hands of police personnel and said they often went hungry. Article 14 could not independently verify these claims.

A video of the clash with officials and police inside the Hiranagar holding centre, located in Jammu’s Kathua jail, shot by refugees and smuggled out.

Parents Attend A Child’s Burial In Handcuffs

Two days after the riot at the Hiranagar holding centre, the shanty town of Kiryani Talab in Jammu bore witness to an event that rippled beyond its boundaries, a reminder of the trials and tribulations faced by the Rohingya refugees seeking refuge in a country in which they once felt safe but has now, they said, has turned hostile to them.

On 20 July, the body of five-month-old Umar Habiba arrived at a Rohingya camp near a mosque called Mecca Masjid Bathindi, Jammu, accompanied by her handcuffed parents.

Chaos ensued among the temporary huts of the refugees when the body arrived, as relatives wept. Habiba was buried that night, as her parents, brother and other Rohingya detainees mourned. Saleem and his wife, Numina, were returned to Hiranagar later that evening.

One Rohingya participant in Habiba's funeral procession told Article 14, on condition of anonymity, of the “indignity” the parents and their teenage son Riazuddin faced, being allegedly handcuffed throughout the mourning. He said, "The parents were treated as if they were war criminals."

Rohingya refugees claimed the police used tear gas indiscriminately without consideration for the children and women in Hiranagar, and it was tear gas that claimed her life.

Kathua senior superintendent of police, Shiv Deep Singh, in an interview with Indian Express, denied any connection between the child's demise and the disturbance in the holding centre.

Officials said that after receiving permission from the district magistrate, the child's parents chose to move the body to Narwal, another Jammu shanty town, where their relatives resided, bringing Habiba’s body to the Rohingya settlement near the mosque at nightfall.

At Risk Of Arrest Or Deportation

Rohingya leaders attributed the difficulties they endure to the policies of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which considers the Rohingya not refugees but illegal immigrants.

While India has sheltered many Rohingya, who were thus potentially saved from being hacked to death—about 24,000 were brutalised during systemic episodes of bloodletting in their homeland—the lack of rights as unrecognised refugees is a constant threat.

The exclusion of the Rohingya from India’s civil documentation process deprives them of access to basic services, such as health and education, said a November 2020 report from the Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, an advocacy group based in the Netherlands, in association with UN Special Rapporteur Tendayi Achiume.

These exclusions are in contrast to recent inclusions and protections that India intends to offer non-Muslim migrant groups from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh through the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019.

As Article 14 reported in January 2020, India excludes Rohingya refugees from essential identity documents, such as Aadhaar, the national identity number but collects biometric data from refugees to aid surveillance and possible deportation.

Refugees who lack documents used to be provided long-term visas to live in India. Many still are. Since 2016-17 the government stopped issuing or renewing such visas to the Rohingya, worsening their already vulnerable situation.

The November 2020 report previously mentioned said that disregard for refugees “puts most refugees and asylum seekers residing in India, including Rohingyas, at risk of arrest and deportation”.

‘We Arrived With Much Hope’

Haseena Begum said when the Myanmar army began attacking and killing the Rohingya, they fled on a journey that took them from their village, Monga, near the Bangladesh border, to the challenges of a Bangladeshi refugee camp and finally to India.

"My family first entered India in 2012 via the Bangladesh-Kolkata border and made their way to Jammu, arriving here in 2013,” said Haseena Begum. “Life was peaceful initially, but recent years have been agonising. I’ve been supporting these children since my son and his wife were detained."

The children want to meet their parents, but the jail authorities do not allow it, according to Haseena Begum. “This is the time to pamper them,” said Haseena Begum. “But they're growing up as if their parents are dead.”

As anti-Muslim sentiment in India has risen, Rohingya Muslims and their children live in constant fear of right-wing extremist attacks in addition to fearing arrest.

Salamat Ullah, 38, was one of those who left Myanmar in 2012. He never thought that they would be treated “like animals” here. "We arrived here with much hope for Indian democracy and big dreams,” he said. “All have vanished in the last few years."

In March 2021, as the government began a drive to identify Rohingya in Jammu, Salamat Ullah fled again, this time to Bangalore with his family to evade detention.

“As soon as we tried to settle down in Bangalore, goons attacked Rohingya families and injured my wife,” said Salamat Ullah. “With no option left, I decided to return to Jammu in March 2023.”

He found nothing had changed in Jammu. Those who were arrested in March 2021 during the verification drive were incarcerated, and their children now live without parents. Education is erratic or absent, and children without parents survive on the goodwill of other refugees, themselves hard pressed to find work.

“We have no choice but to live here," said Salamat Ullah, who now serves as the unofficial head of the Rohingya community at Kiryani Talab. “If the authorities want to deport us,” he said, “they should inform us in advance, so that instead of detaining and separating families, we can leave peacefully and look for another place to survive."

‘We Are Trapped’

In 2017, the union government announced that it would deport the thousands of Rohingya living illegally in India. In April 2021, in a case called Mohammad Salimullah vs Union of India, the Supreme Court ordered that these refugees not be deported without due process of law. But that changed in 2021, when the court cleared deportations.

“We are trapped,” said Salamat Ullah, distraught. “Neither can we go back to Myanmar, nor can we live in peace here. The authorities should kill us all at once rather than make our lives miserable. Like other parents, we also dreamed of a better future for our children, but they are not lucky enough to receive an education and live a life with dignity.”

Most of the children enrolled in local schools have had no choice but to drop out, fearing the police might come and detain them at school. They are confined to their shanties, doing household chores. If they venture out, other children chase them away, said the refugees at Kiryani Talab.

The dangers outside can be fatal, said some refugees, quoting the story of Mohd Shah and Zahida Begum, whose five-year-old daughter Sadiqa Bibi, was kidnapped in 2020, and on the same day, found unconscious in a nearby drain with bleeding ears, her earrings missing. Someone took her to the hospital, but she did not survive for more than one day.

Many other refugees spoke of relatives incarcerated in Hiranagar and how the riot there had increased their dread of what lay ahead. Some said they intended to return to Myanmar when “normalcy” returned, although there appeared to be no immediate hope of that for the Rohingya.

Shafiqa Begum, 26, is one of many Rohingya woman who fled Myanmar to escape possible rape and death and now lives in one of the squalid shanty towns that house refugees in Jammu.

"My parents told me to leave the country somehow to keep myself from getting killed or raped by the Burmese army,” she said. “I entered India via Bangladesh in 2012, my parents arrived here in 2014. I saw how the Burmese army was killing our community and burning our houses. It was terrible."

Shafiqa Begum explained how she was living “a happy life” in India, where she also got married. “But life has turned to hell here as well since the detention of my parents in 2021,” she said. Both parents are in detention in Hiranagar.

Her father, about 60, was detained along with her mother. She cannot comprehend why. “Where can he escape to if he lives with us in this camp?” said Shafiqa Begum. “I have heard my mother fell unconscious inside the jail.”

Noor Jahan, 27, narrated how she spent three years in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, entered India in 2019 with her brother and hoped to restart her shattered life. In 2021, her brother was arrested in the security sweep of Jammu’s refugee camps that March.

"We left our parents in Bangladesh, I got married here and had a son,” said Noor Jahan. “But after the arrest of my brother, I curse my decision to enter India."

How Govt Violates India’s Own Laws

Inside a dank hut in Kiryani Talab, five-year-old Noora and her eight-year-old sister Haleema sat in a corner and listened as adults narrated the violence at Hiranagar, where their parents, Mohammed Ibrahim, 45, and Sajida Begum, 33, have been incarcerated since their arrest in March 2021.

"Everyone is worried about their relatives, and so are we,” said Haleema. “We want to somehow know how our parents are. We run from one judge to another, hoping to get some information about our parents, but this is all in vain.”

Min of the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative said they “regularly” updated the UNHCR and related authorities about the mass detentions and “atrocities” in Jammu. The UNHCR told Min that they were speaking with the government authorities, but there had been no action for over two years.

The refugees expressed disappointment and resentment toward the UNHCR for not intervening or easing the conditions of those detailed extrajudicially. Article 14 sought comment from the UNHCR over email on 13 August, but there was no response.

Meenakshi Ganguly, deputy director of the Asia division of Human Rights Watch, a global advocacy, told Article 14 that it was “extremely concerning” that the authorities in India were failing to protect the rights of Rohingya refugees. The Indian government is aware of the ethnic cleansing campaign by the Myanmar military that has forced the Rohingya to become refugees, said Ganguly

"By arbitrarily detaining them and using indiscriminate force against refugees peacefully demanding protection, the Indian government is grossly violating international standards on refugee rights," she said.

Chatterji, the human rights lawyer previously quoted, said the detention/holding centres in Jammu violate the Model Detention Centre Manual, 2019, the Constitution of India, and the Model Prison Manual, 2016.

‘No Provision For Indefinite Detention’

Chatterji, who is currently arguing a case for Rohingya refugee rights in the Delhi High Court, said the model detention manual requires detainees not only be treated with “human dignity”, but also get basic amenities, such as electricity, drinking water (including water coolers), hygiene, accommodation with beds, toilets and baths with running water, communication facilities, and nutritious food etc. Women, nursing mothers, and children detained in these centres must be given special attention, and families must not be separated in detention. The detainees are entitled to legal aid and representation, and detainees must be able to record complaints, which must be investigated.

"It is important to remember that the Rohingya are foreigners claiming to be refugees, and they cannot be detained until their claim has been assessed in accordance with the standard operating procedures, which are quite clear that both Indian and foreign documents shall be considered to establish a prima facie case for a refugee," said Chatterji.

Even an illegal migrant cannot be detained in civil or administrative detention without being presented before a court of law beyond six months, according to the government rules that deal with foreign national who claim refugee status. According to the 2019 Government SOP "a foreigner claiming to be a refugee" can't be detained until his claim is found to be false.

“There is no provision for such indefinite detention in the rule books of India,” said Chatterji. “It is a complete violation of the right to life and equality before the law that every person, including refugees, foreigners, and illegal migrants are entitled to as per the Constitution of India."

On 14 March 2023, in the case that Chatterji is arguing, Sabera Khatoon vs Foreign Registration, the High Court of Delhi, ordered the union of India, the Foreign Regional Registration Office, and the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board to disclose conditions inside the Shahzada Bagh detention in Northwest suburbs of Delhi and “immediately” hospitalise and provide medical care to detained Rohingya.

"The Courts noticed the poor situation inside the detention centre and ordered the immediate reconstruction of the toilets and the provision of blankets, mattresses, pillows, etc., to the detainees," said Chatterji

On 21 August 2023, Justice G R Swaminathan of the Madras High Court, while hearing the plea of a Sri Lankan Tamil refugee seeking Rs 10 lakh in compensation after his daughter died when a side wall of their settlement collapsed in Tamil Nadu, said the right to shelter, housing and privacy “cannot be denied to refugees living in a camp”.

"There are women and young girls,” said Justice Swaminthan. “Their privacy has to be ensured. Otherwise, there is no meaning in declaring privacy as a fundamental right.”

The court also said it was time to allow refugees to work “without restriction”. None of this is likely to change the condition of the Rohinga in Jammu or elsewhere.

Situation For Rohingya Worsening: Lawyer

The Rohingya living in Jammu hit national headlines in April 2017, when a Jammu-based trader’s body threatened to kill them if the government did not deport the refugees.

In response to a public interest litigation filed by a Jammu lawyer called Hunar Gupta, seeking the deportation of Myanmar and Bangladeshi nationals in J&K, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in April 2022 gave the union government six weeks to identify immigrants staying illegally in the union territory.

Advocate Fazal Abdali, 33, a refugee rights lawyer and researcher with over a decade of experience in refugee litigation, said that the Rohingya were “lawfully” staying and working in Jammu, temporarily, as contract labour, per the provisions of a valid UNHCR card.

"I failed to understand the logic behind the detention of these refugees,” said Abdali. “In the eyes of the law, detention shall only be under the legal provisions, namely, to verify identity and assess the foundation of refugee status or asylum claims.”

“After submitting their information to the authorities, they are still detained,” said Abdali, who added that high courts in various States have “demonstrated a commendable commitment” to upholding their rights (here, here and here) “through a compassionate and reasonable interpretation of the Constitution and statutory laws”.

“The courts have consistently recognised refugees as a distinct and exceptional category, separate from the broader definition of foreigners as outlined in section 3 of the Foreigners Act of 1946,” said Abdali, who added that the right to seek release from arbitrary and illegal detention, commonly called habeas corpus, is “an inherent and fundamental right”, universally recognised in international and regional human rights instruments.

How The Govt Violates Its Own Guidelines

The internal guidelines of the ministry of home affairs relating to foreigners who claim refugee status says refugees ought to be given long-term visas. If the detention period exceeds six months, the individual in question must be released “immediately” after providing biometric particulars, said Abdali, who argued that things were worsening for the Rohingya.

These internal guidelines say that “even an illegal migrant cannot be detained for more than six months". In 1996, the Supreme Court referred to these guidelines in National Human Rights commission vs State of Arunachal Pradesh & Anr (1996).

“The State is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, be he a citizen or otherwise,” the Supreme Court said, ordering the union government to ensure the safety of 65,000 Chakma refugees after a “Quit India” threat to them by the All Arunachal Pradesh Students Union". These guidelines were also quoted in Dongh Lian Kham vs Union of India (2015).

"In the beginning, the Rohingya would secure bail easily, but after August 2017, granting bail to these refugees posed significant challenges,” said Abdali. “The paramount challenge has been and continues to be securing a local surety on their behalf.”

On 13 April 2020, the Supreme Court ordered that foreigners detained at the detention centres in Assam ought to be released “forthwith” on a conditional bail of Rs 5,000, after providing two local sureties. “To my knowledge,” said Abdali, “none of the Rohingya were able to secure this relief due to their inability to provide local sureties.”

(Mubashir Naik and Mehran Firdous are independent journalists based in Jammu and Kashmir.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.