On 21 September 1885, the Bombay High Court delivered a verdict considered extraordinary for its times.

Less than two years earlier, the suit that would come to be known as Dadaji Bhikaji Vs Rukhmabai had seen Dadaji Bhikaji make a legal claim on his conjugal rights with his wife Rukhmabai Raut, married 11 years earlier at the age of 11 years.

Rukhmabai refused to live with him, first citing his poverty, but later questioning the validity of the marriage of a girl before she “arrived at years of discretion”.

On the morning that the case would come up for hearing, the Times Of India carried a letter titled ‘A Hindu Lady’, published under a pseudonym, as well as an editorial.

In his judgement, Justice Robert Pinhey said it would be a “misnomer” to call it a suit for restitution of conjugal rights, for the couple had never cohabited. “And now that the defendant is a woman of twenty-two, the plaintiff asks the Court to compel her to go to his house, that he may complete his contract with her by consummating the marriage,” the judgement said, noting that the defendant objected to allowing Bhikaji to consummate the marriage. It was an act of defiance.

“It seems to me that it would be a barbarous, a cruel, a revolting thing to do to compel a young lady under those circumstances to go to a man whom she dislikes, in order that he may cohabit with her against her will; and I am of opinion that neither the law nor the practice of our Courts either justified my malting such an order, or even justifies the plaintiff in maintaining the present suit,” the judge said.

Rukhmabai’s step-father Arjun Sakharam, a physician, social reformer and one of her early supporters, died before the verdict came.

Judge Pinhey’s verdict, however, went on to become a contest between the English legal system and Hindu society, with Bal Gangadhar Tilak, one of Rukhmabai’s fiercest critics, blaming her education for her rebellion.

The nationalists forced an appeal in the case, and a fresh trial ensued, with the judge ruling against Rukhmabai this time. Eventually, the case ended in a settlement, but Dadaji Bhikaji Vs Rukhmabai captured a moment in which the Hindu orthodoxy witnessed the power of an educated woman.

In 1891, the British-Indian legislation titled the Age Of Consent Act raised the minimum age for brides, but only from 10 years to 12 years.

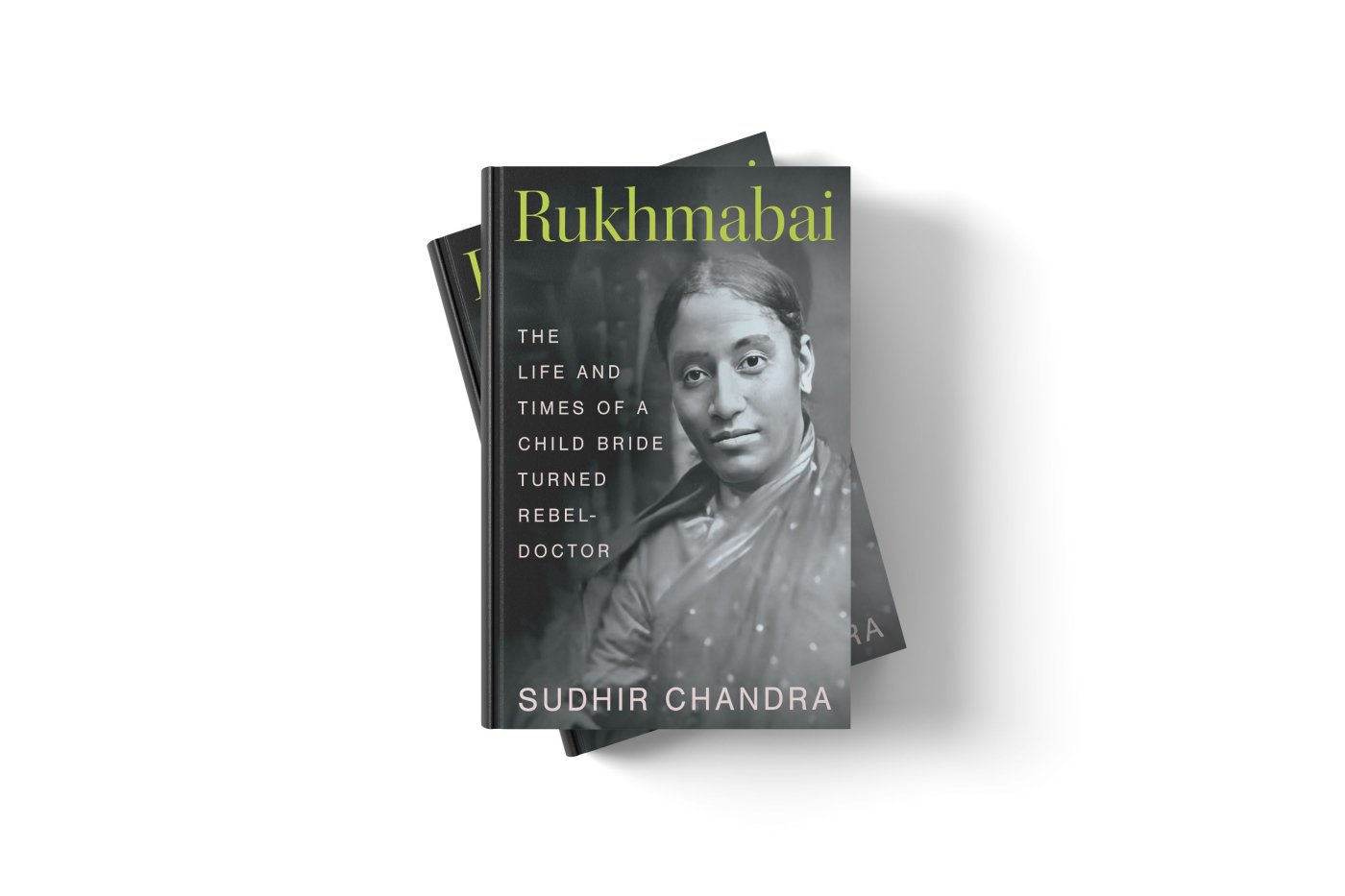

An authoritative new biography of the overlooked feminist icon from the nineteenth century now traces the story of a child bride who took on the patriarchy. With the help of the support her case garnered for her, Rukhmabai went on to study medicine in London, becoming India’s first woman medical practitioner.

Sudhir Chandra, author of Rukhmabai: The Life And Times Of A Child Bride Turned Rebel-Doctor, writes that his protagonist had anticipated “the power of satyagraha before satyagraha was known”.

EXCERPT

Rukhmabai had heralded a new conception of woman as a person.

Rukhmabai’s plea, expectedly, was seen as outrageous. It threatened the very basis on which rested the two pivotal institutions of Hindu society: Hindu marriage and the joint family. Early marriage was then the norm among Hindus, and it was an arrangement between two families. To claim the right to disown one’s marriage on the ground of absence of intelligent consent was pure subversion. If recognized, the right would expose every child marriage to the potential risk of being disowned by a spouse after attaining the age of discretion. Recognition of the right to suitable lodging would jeopardize the institution of the joint family.

Rukhmabai’s radical plea before the High Court soon found elaborate articulation in the letters of ‘A Hindu Lady’. This is evidence enough that the plea was not entirely the work of the solicitors. It was, demonstrably, the plea of a woman who, having as a child taken seven steps with a stranger and seen him ‘go through every course of dissipation’ in subsequent years, had finally resolved to undo those fatal steps.

It is a measure of Rukhmabai’s heightened sensitivity and awareness that she did not resolve upon that extraordinary action because her sufferings were extraordinary. If anything, she was relatively better off than most of her suffering sisters. Yet, it was she who rose up, and offered a resistance that had not been conceived of before.

Revolutions are often initiated not by the poorest and the worst oppressed within a system, but by the relatively better off among them.

Rukhmabai’s resolve overrode even her fear of appearing in a law court. When they first met, Rukhmabai nervously asked Nora Scott: ‘Must a woman go herself into the court if she has a suit?’ Dadaji had already filed the case. She was hoping that the judge’s wife might suggest a way to avoid personal appearance. Rukhmabai’s fear was part of the general dread that respectable middle-class people had of law courts. Officials and lawyers apart, law courts were not meant for such middle-class folks, certainly not for their women.

Rukhmabai was fortunate that her case came up before a judge, Justice Robert Hill Pinhey, who was sensitive enough to grant her exemption from physical appearance. Other judges would be different.

On 16 April 1885 Sakharam died. For Rukhmabai that was a crippling blow. Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai had been filed a year ago, but had not yet come up for hearing. And she had lost her lone rock of support in the family. Their notion of family honour and dread of litigation intact, Jayantibai and Harishchandra were unlikely to back her. The case might be dropped before it had really begun.

Rukhmabai now had to protect herself from her mother and maternal grandfather. She had to try and shake them out of their traditional thinking. Time was running out. The case could be listed for hearing any day. The only saving grace was that outside of the family there were well-wishers like Edith Pechey who would not let Rukhmabai despair.

She succeeded. The mother no more demurred; and, even though he could not quite step into Sakharam’s shoes, the grandfather decided to take up the unfortunate granddaughter’s cause.

Rukhmabai was lucky that her resistance coincided with another event of great public importance. Within months of the filing of Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai, Behramji Malabari initiated with his celebrated ‘Notes on Infant Marriage and Enforced Widowhood’ the movement that would eventuate in the epochal Age of Consent Act. Just as he commenced his campaign for legislation, Malabari was advised to collect a few ‘test decisions’ by courts of law. That would demonstrate the inadequacy of existing laws and the need for fresh effective legislation. Precisely when Malabari received this advice he stumbled upon Rukhmabai’s case. The coincidence was a godsend for both Rukhmabai and Malabari.

A master strategist, Malabari was quick to grasp that Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai alone would establish the urgency of fresh legislation. With his deep identification with women – ‘I am the widow,’ he famously said – his knowledge of society, politics and history, his powerful pen and caustic wit, he would emerge, through his weekly, the Indian Spectator, as the most powerful public voice on the case. He would also work behind the scenes to gather organizational support and funds for Rukhmabai.

Around the same time, Henry Curwen (1845–92) also came over to Rukhmabai’s cause. An accomplished writer, Curwen wielded enormous influence as the editor of the Times of India. He ensured elaborate pro-Rukhmabai coverage of the case. And before that, he devised a brilliant plan to create an atmosphere in favour of Rukhmabai. He got her to write the letters of ‘A Hindu Lady’ which we have followed at length in the previous chapter. He encouraged her to write freely and without worrying about space. In an extraordinary move, Curwen inserted editorials that exhorted the readers to read and reflect on the letters.

The timing of the letters was planned with great tactical acumen. The first letter was published in the wake of Malabari’s ‘Notes’, and it began with an appreciative mention of them. The idea was to heighten the effect of the ‘Notes’ by supplementing them with the searing testimony of a woman. The letter created an air of suspense and expectancy. Who was this mysterious ‘Hindu Lady’? What would she say in her next letter? When would that be?

The second letter was even more brilliantly timed. It was published the day Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai came up for hearing. It made sure that the judge – Mr Justice Pinhey – would have read the piquant exhortation of ‘A Hindu Lady’ before hearing Rukhmabai’s case. He would not miss the uncanny similarity between the two unfortunate women. That, indeed, is how it went. The timing also ensured a similar sympathetic response among the thousands of readers of the Times of India. Their response to the shocking revelations in the young helpless woman’s case was so much the sharper for having read the previous day’s lament of ‘A Hindu Lady’.

The plan aroused no immediate suspicion. Subsequently, however, Hindu orthodoxy, wised up by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, complained that this was a conspiracy to put the judge under psychological pressure.

Curwen reminds one perforce of Grattan Geary. We have met him in the first chapter where we had a glimpse of his thorough exposure of Narayan Dhurmaji. Geary was the editor of the Times of India when Curwen, freshly arrived from London in 1876, joined the paper as his deputy. Within four years Curwen managed a coup and replaced Geary, who in turn took up the editorship of the Bombay Gazette, the city’s oldest newspaper. Their rivalry became so intense and public that people avoided inviting both of them to the same function. For an entire decade the rivalry provided colour and verve to Bombay’s public life, before ending with Curwen’s death in 1892.

Compared to Curwen, Geary was late in throwing his weight behind Rukhmabai. In fact, his first response to her – to ‘A Hindu Lady’ rather – was critical. Ever ready to support a good cause, Geary hated political correctness. He knew the miseries of upper-caste women. But he also knew that widowhood was not universally ‘enforced’ in India. Lower-caste women, who formed ‘the bulk of the community in the mofussil’, laboured under no such disability. Indeed, as one whose own widowed mother had remarried, Rukhmabai should have known that, and refrained from portraying widowhood as a universal practice among Hindus. Citing ample evidence, it was on this ground that Geary faulted ‘A Hindu Lady’.

But Geary became an ardent supporter of Rukhmabai from the moment her case came up for hearing in 1885. The following year, when it became clear that the case would drag on and cost a fortune, he even started a fund to help Rukhmabai, who had it immediately closed. Later on, when the Rukhmabai Defence Committee was formed, Mrs Geary became its member. So unqualified was Geary’s support to Rukhmabai that he was even dragged in a contempt case by Narayan Dhurmaji.

Such was the power of Rukhmabai’s cause that both the archrivals, Curwen and Geary, supported her enthusiastically. Only towards the fag end would Curwen cave in.

The stage was ready for a great judicial drama. Initially it was decided that Rukhmabai would be represented by two legal luminaries, Kashinath Trymbak Telang and John Duncan Inverarity, with both of whom Sakharam was on friendly terms. Both he and Telang were prominent public figures who shared a deep commitment to social reform and educational projects. Inverarity, by far the most sought after barrister of the Bombay High Court, was among the earliest and most enthusiastic members of the Bombay Natural History Society, of which Sakharam was a founding member.

A third legal luminary was later added to the team. This was F. L. Latham, the Advocate General of Bombay.

(Excerpted with permission from Rukhmabai: The Life And Times Of A Child Bride Turned Rebel-Doctor published by Pan Macmillan India.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.