Guwahati: The Assam government has quietly instructed district authorities and Foreigners’ Tribunals (FTs) to drop cases against Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and Parsis—if they entered the state on or before 31 December 2014.

The justification: these individuals fall within the ambit of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019.

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has denied issuing any fresh or special directive to drop such cases, saying the government is only following provisions already in the CAA.

“If there is any cabinet decision, I always come and share it with you. No special decision has been taken,” he told reporters on 8 August 2025.

Sarma said protections for these groups stem solely from the CAA, which remains “the law of the land unless the Supreme Court strikes it down,” and clarified that formal withdrawal orders have so far been issued only for the Koch Rajbongshi and Gorkha communities, not the six communities named in the Act.

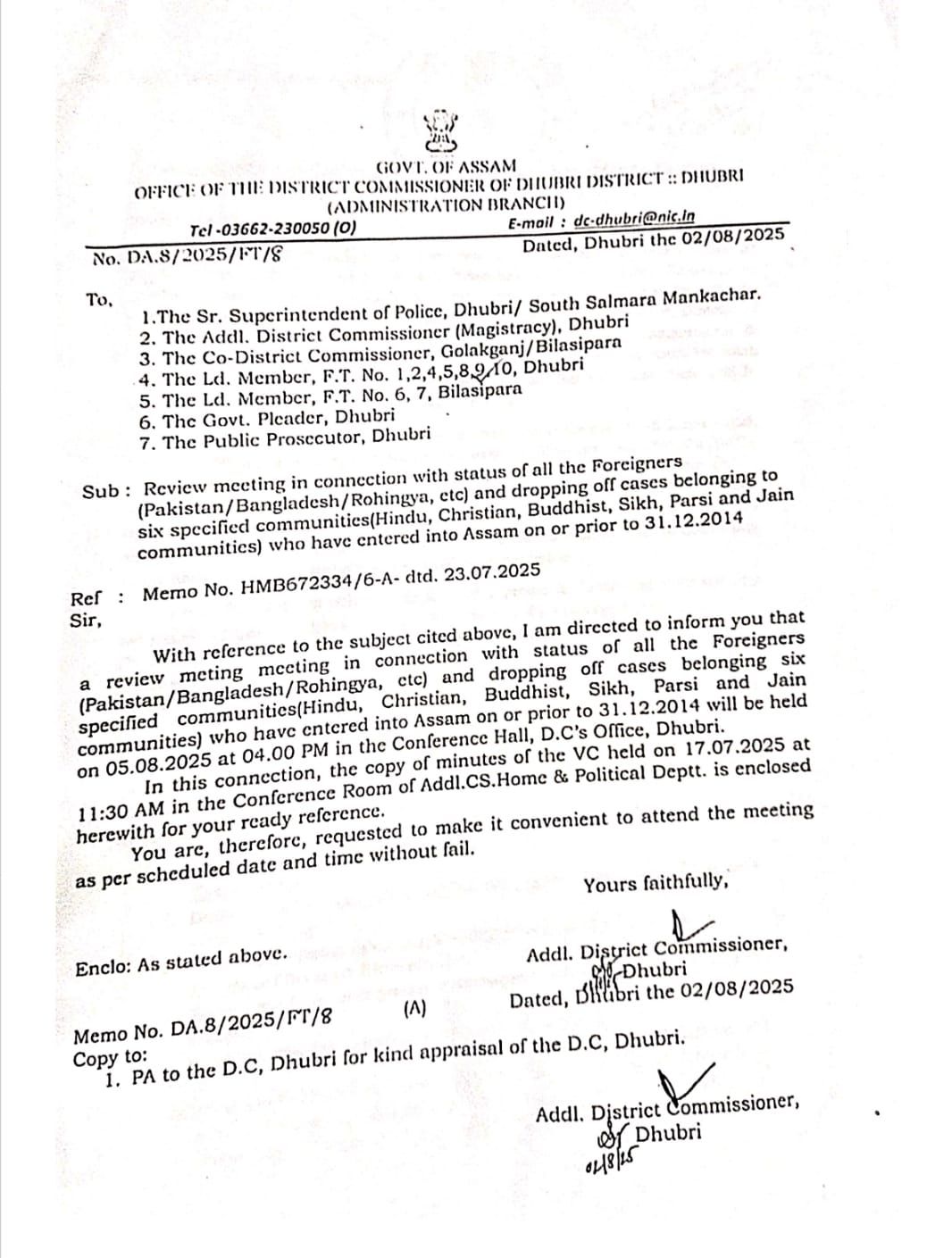

The directive followed a 17 July 2025 meeting chaired by senior officials from the state’s Home and Political Department, Scroll.in first reported on 5 August 2025.

The meeting minutes stated that FTs “are not supposed to pursue cases of foreigners belonging to the six specified communities (Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh, Parsi, and Jain) who had entered Assam on or before 31.12.2014.”

District commissioners and senior superintendents of police were asked to “immediately convene a meeting with their respective FT members, review developments periodically, and submit action-taken reports to this department.”

A senior government official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Article 14 that the directive should be seen as “a set of suggestions and ongoing discussions” rather than a formal legal notification, adding that such cases will be treated under the amended Citizenship Act.

Legal experts and human rights lawyers said the directive sets a dangerous precedent—disregarding both the CAA’s stated criteria and constitutional norms of equal treatment under law.

The CAA, passed in December 2019 and operationalised only in March 2024 after long delays, offers a route to Indian citizenship for undocumented non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh—if they can prove they fled religious persecution.

But Assam, where migration and identity politics are inextricably linked— and Bengali-speaking Muslims have been gradually excluded—has been slow to implement the Act amid resistance from regional parties and civil society.

Over the past seven to eight months, the Assam government has demolished over 5,333 homes, the overwhelming majority belonging to Bengali-origin Muslims, in seven separate eviction drives. While officials claim that these evictions are to remove "illegal encroachments", experts and activists argue that many of the evicted had settled on government or forest land after losing homes to repeated floods and river erosion caused by the river Brahmaputra.

"Don't take tension about eviction. It's a different department which will decide whom to evict. There will be no eviction against any Indian or Assamese people, just keep this in mind,” Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma had said on 2 August 2025 while addressing concerns about eviction drives in Assam and assured that indigenous people and Hindus will not face eviction.

A Quiet Bypass of Law?

Assam’s FTs, quasi-judicial bodies created to identify undocumented foreigners, have long been criticised for opaque processes and inconsistent rulings.

Their judgments—often without access to legal aid, reliable documentation, or even proper notice—have declared over 165,000 people foreigners as of January 2025, as Article 14 reported on 12 January 2022.

In that context, the state's move to selectively withdraw cases on religious lines has triggered a wave of legal unease.

“If someone entered India within the CAA timeline, they already have a pathway to apply for citizenship,” said a Guwahati-based lawyer who requested anonymity. “Why is the government short-circuiting this by unilaterally dropping these cases?”

The lawyer questioned how the government could presume all such migrants were persecuted minorities: “What if they are economic migrants? What if they never faced religious persecution at all?”

This, experts argue, is the central flaw.

The CAA is not a blanket amnesty but requires applicants to establish they fled religious persecution. “The tendency to apply these exemptions unilaterally, rather than individually, defeats the law’s intent,” said Darshana Mitra, assistant professor at the National Law School of India University (NLSIU), Bangalore.

Senior Assam advocate Santanu Borthakur echoed the concern: “Nowhere in these FT cases has anyone claimed they faced religious persecution in Bangladesh. Most claim they were born and brought up in Assam and that India is their home.”

That contradicts the CAA’s basic eligibility requirement. “The government cannot say these people are persecuted refugees while the same people claim they’re Indians by birth,” Borthakur said.

A senior government source, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to talk to the media, told Article 14 that the directive should be viewed as “a set of suggestions and ongoing discussions”—not yet a formal legal notification.

The D-Voter Trap

The government’s move may bring little respite to ‘D-voters’—people marked as “doubtful” citizens in electoral rolls.

D-voters are barred from voting and often live in legal limbo for years. Even if their FT cases are dropped, their disenfranchisement persists.

“This is especially problematic,” said Mitra. “Dropping a FT case does not remove the D-tag. These individuals remain disenfranchised, unable to access critical rights and documentation.”

Only by actively contesting and clearing their names in tribunal proceedings can D-voters escape this status. “Unless the Election Commission issues a directive to remove the D-tag for affected groups, the state government is powerless,” she said.

For many legal experts, this highlighted the arbitrariness of the system.

“These cases shouldn’t exist at all,” Mitra argued. “Withdrawing cases for one group may bring temporary relief, but it entrenches discrimination. The crisis is the existence of the Foreigners Tribunal system itself, which disproportionately targets Muslims.”

Muslims in Assam are severely affected by the state's citizenship adjudication process through FTs, as detailed in the recent joint report by Queen Mary University of London and the National Law School of India University (NLSIU). The report titled "Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture of Rights Violations and Exclusion in India’s Citizenship Trials" documents over 1,65,000 people declared foreigners by these tribunals as of January 2025, with a large proportion being poor marginalised Muslims.

Political Messaging

The timing of the directive is politically significant. With state elections due in 2026, the move is being read as a signal to Assam’s sizeable Hindu Bengali electorate—by some estimates between 19% to 25% of the population, although there is no accurate data.

Figures based on the 2011 Census indicate that as of 2024-25, Assam’s population is predominantly Hindu, approximately 61.47% of the total, while Muslims make up the second-largest religious group at around 34.22%. Other religious minorities account for the rest.

“This is clearly political messaging,” said the Guwahati-based lawyer. “It sends a message of protection and inclusion to a specific demographic in the run-up to elections.”

Borthakur estimated that more than 50,000 Hindu Bengalis stand to benefit from the move—enough to swing three to five constituencies.

“On the one hand, the government says it wants to remove illegal immigrants,” said Borthakur. “On the other hand, it facilitates the settlement of a large group without ensuring they meet even the CAA’s basic condition of religious persecution.”

The lawyer added: “What’s now left is that the Foreigners Tribunal system will be almost exclusively for Muslims, who alone must prove their citizenship. It reinforces both the perception and the reality of religious discrimination.”

AASU: Violation of Assam Accord

The All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), a powerful force behind the anti-immigrant Assam Agitation of the 1980s, has come out strongly against the directive.

In a statement on 7 August 2025, AASU President Utpal Sarma denounced the decision to withdraw cases against Hindu Bangladeshi migrants and announced plans to burn copies of the directive across the state on 8 August 2025.

Reasserting the principles of the 1985 Assam Accord, which mandates the expulsion of all undocumented migrants regardless of religion if they entered after 1971, AASU said the government’s action violates the very foundation of Assam’s modern political consensus.

2 Sets of Rules

The government’s order, though framed as an administrative streamlining exercise, appears to do more than that. It risks cementing a dual-track citizenship regime—where non-Muslims are shielded from scrutiny and Muslims are left to navigate a hostile and opaque system of suspicion.

Legal scholars interviewed by Article 14 warn that the directive not only bypasses legal due process, but by doing what it is, Assam’s government is not just deciding who deserves to stay—but who gets to belong.

(Sanskrita Bharadwaj is an independent journalist from Assam.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.