Updated: Aug 13, 2020

New Delhi: Devangana Kalita’s friends had never seen meteor showers until the night of 13 December 2018, when she gathered them on the terrace of her flat in north Delhi. Knowing some, including flatmate Natasha Narwal, were upset for not letting them sleep, she ensured a generous supply of tea.

Half asleep and groggy, they all sat up when Kalita’s promised celestial fireworks began.

“Wow! This is how we will grow old,” Nimisha Agarwal, who was on the terrace that night, recalled them saying. “On most of the occasions, friends would crib listening to Devangana’s plans. Then she gives them that wide smile and they would budge.”

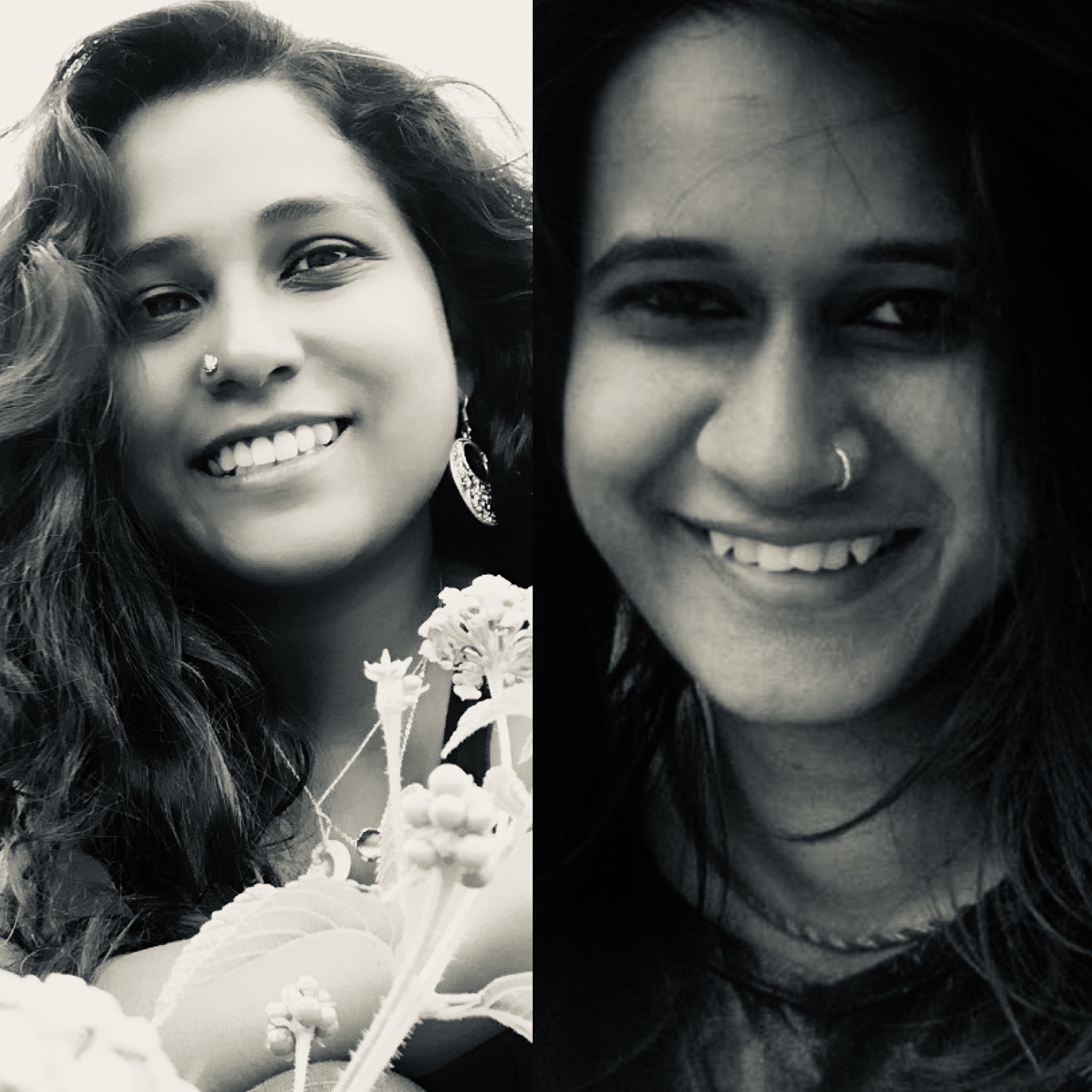

Friends and families remember Kalita and Narwal, both 31, as friends with common interests in poetry, stargazing, and upholding “progressive politics”.

M.Phil and PhD scholars respectively at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and members of a students collective called Pinjra Tod, Kalita and Narwal have been in prison for 73 days, after being arrested on 23 May. The Delhi police have accused them and at least 12 other vocal critics of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), 2019, of instigating riots that claimed 53 lives in northeast Delhi between 23 and 25 February 2020.

The Delhi police have accused them of 33 offences under various sections of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act, 1984 (an explanation of the Act is here), the Arms Act, 1959, and the anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967. The offences against Kalita and Narwal include murder, terrorism, rioting, dacoity, criminal conspiracy and sedition.

On 27 July, the Delhi high court ordered the Delhi police not to issue any communication naming any accused in this case till the charges, if any, are framed and the trial begins.

Kalita’s lawyer, Adit Pujari had moved the High Court about a police note, shared with journalists on 6 June, alleging that “Pinjra Tod members including Kalita were actively involved in hatching a conspiracy to cause riots near Jaffrabad metro station”.

Pujari argued that the Delhi Police “leaked information selectively to the media with a view to spread false propaganda against the petitioner and prejudice public opinion”. Additional Solicitor General Aman Lekhi, representing Delhi police argued that the purpose of the Delhi Police’s note was “not to prejudice the trial against Kalita but to accurately portray the case in view of a media campaign carried out by Pinjra Tod members and their supporters to sway public opinion against the actions of the Delhi Police”.

National and global civil rights bodies have criticised a police crackdown on CAA dissenters, a move that continued through the Covid-19 lockdown and was linked by the police to the Delhi riots at a time when courts were partially functioning, legal access was limited and overcrowded prisons were potential coronavirus hubs.

Protest, Politics & History Interest PhD Student Narwal

Animated, dreamy, nurturing and “occasionally silly”, is how those who know 31-year-old Kalita describe their Assamese friend, who was partial to eating fish, duck, pork and rice. “Her stress busters are painting and the hoola hoop,” said Agarwal.

Narwal, 31, is calm, measured and prefers living in a cocoon. “She is the most silent one in the room,” said Anjali Chahal, Narwal’s friend for the past 10 years. At gatherings, she preferred spending hours talking to someone familiar. ” Every time Chahal grew impatient, Natasha would tell her: “Faqat chand roz meri jaan (a few more days my dear).”

Much before Kalita and Narwal gazed at the meteor shower that winter night in 2018 as friends, they exhibited personality traits that endeared them to each when they eventually met. While studying English literature at Miranda House College, Delhi University (DU), Kalita contested college council elections as an independent candidate and became the vice president. “She was not okay with the status quo,” said Agarwal. “The idea was to constantly question the system to change things for the better.”

Seema Srivastav, one of Kalita’s friends from her undergraduate days said they realised most candidates fighting university elections made “a mockery of the code of conduct”, which prohibits the use of vehicles, loudspeakers and printed posters/pamphlets for canvassing.

“We launched a meticulous and personalised campaign,” said Srivastava. Along with other students, Kalita resisted hostel curfew hours and routinely participated in protests within the college and beyond, on issues that ranged from safety on campus to takeover of tribal land in Niyamgiri (Odisha) by the aluminium conglomerate Vedanta Limited. Kalita was interning with Seva Mandir, a nonprofit in Udaipur, Rajasthan, where she met her future husband. They married in the UK in 2014.

After finishing her masters (gender and development) from the University of Sussex, UK, Kalita returned to India. “She did not go with the intent of staying back,” said Srivastav. “And London is too cold for her. She likes the sun here.”

Kalita was drawn to events that resonated with her—contesting right-wing diktats against Valentine’s Day in 2015 and a campaign in Dehi’s Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI) University to create awareness about menstrual hygiene, the same year.

Kalita opted for M.A. (History) at JNU as her second masters. Narwal liked to study the past to understand the present.

“She is passionate about Delhi and its history,” said Narwal’s friend, Akhil Katyal, assistant professor, Dr BR Ambedkar University, Delhi. “She would discover the city and share it with her friends over long walks around the Roshanara tomb and Coronation Park.”

During the five years Narwal pursued history at DU, the Students’ Federation of India (affiliated to the Communist Party of India) fielded her as its candidate for the posts of president (2007) and joint secretary (2009) in Delhi University Students Union elections. She lost both elections An M.Phil in development practice at Ambedkar University took her to Odisha, where she focused on access to land rights for tribal communities in Rayagada district. “She took the action research methodology, immersing herself with the locals and looking at the world from their viewpoint,” said Anil Persaud, associate professor, who supervised Narwal’s dissertation.

Whenever she wanted alone time, particularly as examination neared, Narwal would undertake short trips to Rohtak (Haryana) to live with her father, Mahavir Narwal, PhD, a retired senior scientist from the Haryana Agricultural University.

After a short sabbatical from academics, Narwal became a Ph.D candidate at JNU’s Centre for Historical Studies.

Pinjra Tod: A History Of Protest

In 2015, Kalita’s and Narwal’s paths crossed, changing their lives forever.

Early that year, Kalita’s flatmate and queer activist Vikramaditya Sahai introduced her to Narwal. After a few weeks, Narwal moved in with them, and the three have lived together since.

“They’ve had very different lives before they came together. In a sense, their friendship is a political space,” said Sahai.

In August 2015, the JMI administration banned “late night” outings for women students living in its hostels. An anonymous open letter was sent to JMI’s vice chancellor criticising the move and a petition was filed before the Delhi Commission for Women. Resistance by Jamia students inspired similar protests in other universities. A Facebook page ‘Pinjra Tod: Break the hostel locks’ became a platform to document the experiences of women students.

In the early days, Pinjra Tod activists, including Kalita, were unsure how students would respond to the campaign. “So far it’s not been very difficult, in terms of people taking their own initiative,” Kalita said in an interview to Youth Ki Awaaz in October 2015. “I think [keeping] the momentum going [is going] to be difficult.”

In the months that followed, a wave of protests nationwide questioned policies and rules regarding women students. While curfew hours remained the core issue of protest, the Pinjra Tod collective backed demands for 24X7 eateries for women students, access to sports facilities at night and equal hostel fees for men and women.

Writing for IndiaSpend in April 2019, writer Annie Zaidi noted that Pinjra Tod saw itself as “a network of solidarities” rather than an organisation. There is no membership or affiliation; it keeps the focus on issues over individuals; and anyone probing the collective is unlikely to find its leaders or founders.

As the collective’s influence spread, so did clashes with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the student wing affiliated to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). “On many occasions, discussions on our dinner table were about the sustained campaign to discredit Pinjra Tod activists,” said Sahai.

The collective’s Facebook page reveals it backs organisations and movements against political, social and cultural discrimination. Its activists travelled to Gujarat in 2017 when Dalit leader Jignesh Mewani protested against caste atrocities. They have organised marches and public meetings on issues that include a security crackdown in Kashmir, labour reforms, privatisation of education and incarceration of political activists.

“They (Pinjra Tod) have localised the movement to reflect South Asian patriarchy, which ties in with elements of caste, class and the politics of reproduction," feminist historian Uma Chakravarti told Mint in December 2016.

So, when protests against the CAA and the National Register of Citizens, a controversial, proposed count of all Indian citizens, gathered momentum in Delhi in January 2020, Pinjra Tod activists jumped right in.

The Crackdown And The Prosecution

Sometime in May 2020, Kalita phoned Nimisha Agarwal from a new number. The preceding month, the Delhi police had seized the mobile phones of both Kalita and Narwal.

During a nationwide lockdown that followed the coronavirus outbreak, the Delhi police started arresting critics of the new citizenship law. “There was a sense of despair in Dev’s (Devangana Kalita) voice,” said Agarwal. “She could not fathom what the state was up to. On a lighter note, she said that if something happens to her, I should inform her professors.”

On 23 May, after interrogating Kalita and Narwal for around two hours at their flat, the Delhi police arrested them in connection with FIR 48/2020, a first information report that accused them of being part of the group that led an anti-CAA protest beneath northeast Delhi’s Jaffrabad metro station without official permission.

The following day, both got bail, but were rearrested in another police case filed in FIR 50/2020, after the Delhi police crime branch successfully won court permission to interrogate them in connection with the death of a local during the riots.

Additional Sessions Judge Amitabh Rawat rejected their bail pleas in FIR 50 on 14 June on the ground that there was “no merit” in their applications. On June 6 and May 28, the Delhi Police also invoked against Kalita and Narwal the anti-terror law, UAPA, in another case, FIR 59/2020. At least 10 others, including Jamia scholar Safoora Zargar (read Article 14 story on her here), JNU student Umar Khalid, Congress councillor Ishrat Jahan and social activist Khalid Saifi were already named in this FIR. In addition to the three FIRs naming both of them, Kalita was arrested on 30 May in connection with a fourth FIR, for allegedly participating in protests in Delhi’s Darya Ganj on 20 December 2019.

Metropolitan Magistrate Abhinav Pandey granted Kalita bail in this case on 2 June. “No direct evidence attributable to the accused has been found to bring her (sic) for the offences under [sections] 325 (punishment for voluntarily causing grievous hurt)/353 (assault or criminal force to deter public servant from discharge of his duty) of IPC,” he said.

Sahai is hopeful that his flatmates will be back with him some day, to have those discussions, commune with one another, and, perhaps, look to the stars again. “They are missing,” he said, “but not absent.”

*Pinjra Tod members and lawyers of Kalita and Narwal declined interview requests for this article as the cases are sub-judice or under trial

*Some names have been changed to protect identity

(Danish Raza is a New Delhi based journalist. He writes on social justice, culture and the convergence of technology and society. His work has been published in Hindustan Times, The Guardian and The Atlantic.)