Delhi: “…they have (sic) threaten us unfairly when they brought us from navy to boat, they bind our hands, our hands bleed and do not let us to (sic) move our head from up to down, they kept us in this way (sic) about 3-4 hours in the boat.”

This excerpt is from a phone call between a Rohingya Muslim refugee and his family after he was allegedly forced off an Indian navy vessel into the Andaman Sea with a life vest and sent back to Myanmar, where they have faced genocidal acts—mass killings, rape, and destruction of their villages—because of their religion and ethnicity.

This transcript of a recorded conversation between a man and his family was part of the petition submitted to the Supreme Court on 10 May, with a plea to submit additional documents on May 12.

The petition, heard on 16 May, claimed that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government “illegally deported” 38 Rohingya refugees, including women, children, the elderly and sick people, to Myanmar on 7 May, "abandoned" them in international waters, compelling them to swim to the shore.

Despite a tape recording of the conversation and several media reports featuring interviews with family members of those deported claiming the same, strongly worded remarks from a United Nations expert on human rights on the “unconscionable, unacceptable acts”, and names of the 38 deported in the petition, the Supreme Court said that there was no evidence indicating that the Indian government had left the Rohingya refugees stranded in international waters.

So far, the union government has neither confirmed nor denied these accounts. The fact-checking unit of the press information bureau, which quickly negates media reports that show the government in a poor light or highlight state failures and excesses, has not issued any clarification.

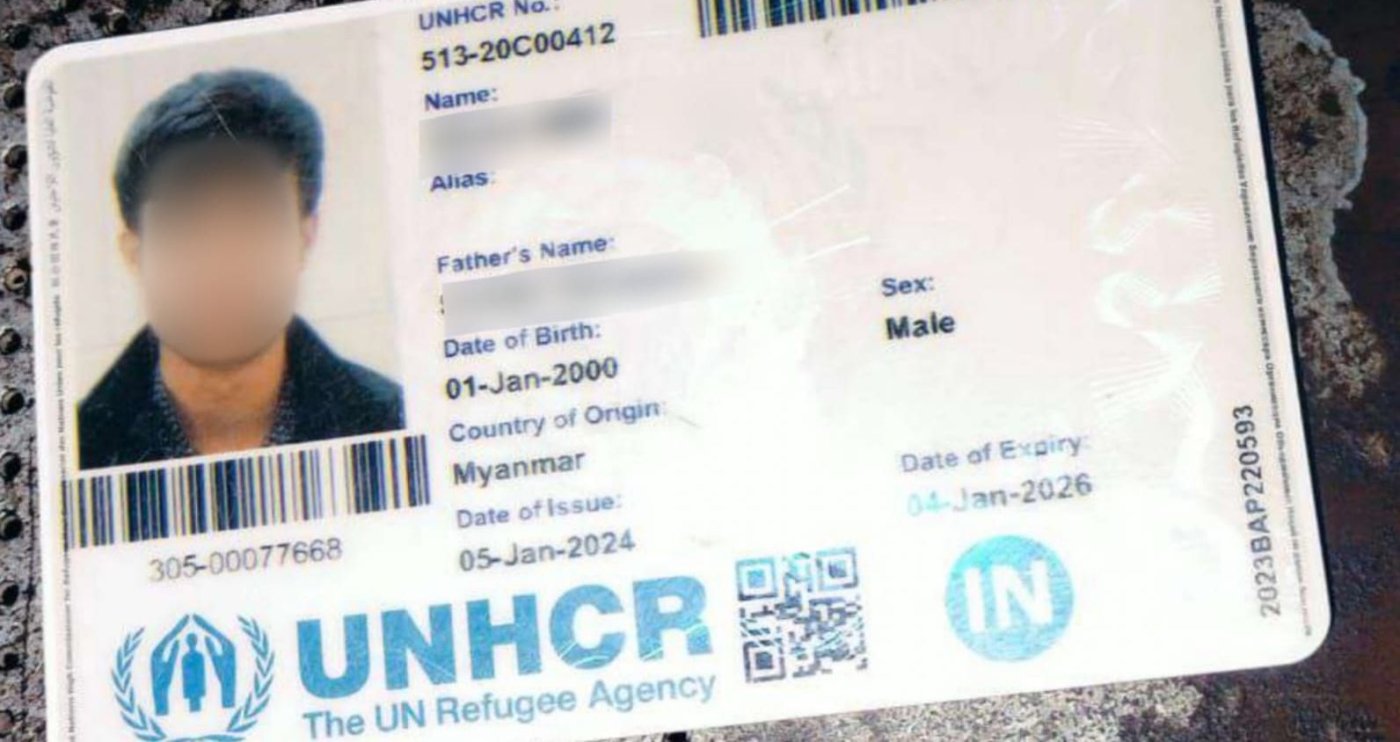

All 38 refugees deported had identity cards issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations agency tasked with protecting refugees, stateless people, and forcibly displaced individuals.

These cards, historically, have meant that India recognises them as people fleeing persecution, distinguishes them from undocumented migrants, and affords them protection. Article 14 has reported (here, here and here) on the escalating harassment of Rohingya Muslims in the years since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014.

‘A Beautifully Crafted Story’

The first petitioner, Mohamaad Ismail, 44, said police took away his sister and niece on 6 May in Delhi, according to the petition. The second petitioner, Noorul Amin, 25, said the police took away his mother and father, elder brother, younger brother, and sister-in-law.

Family members accused the police of physical mistreatment and extended detention of women and children without food or female police officers present. The petition features two images depicting the alleged physical abuse at a police station in Delhi.

On 16 May, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court questioned the petition that sought the return of the deported Rohingyas and an end to future deportations.

The petition, Justices Surya Kant and N Kotiswar Singh said, was “fanciful,” “a beautifully crafted story,” and “absolutely no material in support of the vague, evasive and sweeping statements made”.

Justice Kant remarked to the lawyer presenting the case, senior advocate Colin Gonsalves, “Every day you come with one new story. What is the basis of this story? Very beautifully crafted story. Please show us the material on the record. What is the material to substantiate your allegations?”

Live Law reported that Gonsalves informed the Supreme Court that those deported had called their family members, and there was one taped conversation that could be verified.

Still, Justice Kant said the petition lacked “prima facie material” and “absolutely no material in support of the vague, evasive and sweeping statements made.”

"When the country is going through a difficult time, you come out with such fanciful ideas,” Justice Kant said. He said, “Every day you keep collecting material from social media…”

‘Just Call The Legal Officers & Ask Them’

When we talked to Gonsalves on 17 May about the court’s observations, the lawyer said that “sufficient evidence” had been presented to the Supreme Court and asked why the government had not publicly refuted the claims in court.

Proving a case beyond a reasonable doubt is a legal threshold typically applied to the state in criminal cases. In this case, the Rohingyas were asked to provide that proof, said Gonsalves.

“Why is the conversation between the man and his family, recorded on the like and transcribed, not definitive?” said Gonsalves. “He is there on the shores of Myanmar. He has got a phone, and he is talking to me. I’ve recorded it and given it to the Supreme Court.”

“Now look at it from another angle. Why should I give proof of deportation when the Indian government has done it?” said Gonsalves. “Why is everyone putting the burden on our shoulders as if it is a criminal case that I must prove beyond a reasonable doubt?”

“Why should the government counsel not turn up and say, sir, we have not deported them?” said Gonsalves. “That would put an end to our case because a definitive statement from the government on affidavit would for sure be accepted. Why the silence?”

Asked if the Supreme Court should institute a court-monitored inquiry, Gonsalves said, “Why should an investigation be initiated? Just call the legal officers and ask them.”

‘They Just Threw Us & Went Back’

The conversation between the Rohingya man, Anwar, and his family continued:

“After we came by the boat they bind (sic) a rope in a tree and threw us in the sea, they gave each of us a life jacket, with which we saw and reached the seashore; they said that after one or two hours people will come to take us but it has been so long now, yet no one came to take us, they just threw us and went back. Now we called you with the help of a local fisherman’s phone.”

“They (The naval officers) told us that they will give us to Indonesia; they asked us, whether will you (sic) go to Myanmar or Indonesia? We replied, Indonesia because there is UNHCR and we will get assistance from them but they brought us to Myanmar. After our arrival on the seashore, when we (sic) on the phone of one of us, although there is no sim, the location shows that we are near Yangon, after we open (sic) Myanmar network signal it is showing Burma and when we spoke with the people, we found out this is Burma.”

The petition asked the court to describe the deportation on 8 May as “unconstitutional and unjust”, bring the Rohingyas back to New Delhi, release them from custody, treat them with respect and dignity, pay each Rs 1 crore as compensation, and not deport the Rohingya to any other country.

Persecuted People

There are more than 1.4 million Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers, including, according to government records in 2017, more than 40,000 in India, mainly staying in Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and Rajasthan.

According to the UN, there are 83,499 refugees and asylum seekers in India, the third highest after Bangladesh and Malaysia, with more than 57,700 coming in since February 2021.

India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, which outlines the rights and protections given to refugees. Still, it has always granted asylum to many refugees from neighbouring countries, afforded protection to people with UNHCR documentation, and respected the international law principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning a person to a country where they face a real risk of persecution.

As per the government’s internal guidelines—issued in December 2011 and included in the petition— to “deal with foreign nationals in India” who claim to be refugees, if a claim of fear of persecution is found to be justified, the ministry of home affairs will grant a long-term visa within 30 days from the date of claim.

In The Courts

In a Supreme Court hearing on other petitions on the detention and deportation of Rohingyas on 8 May, the solicitor general of India, Tushar Mehta, said India did not recognise them as refugees and they would be deported according to the law.

Mehta referred to an April 2021 interim order in which a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, including the then-Chief Justice, S A Bobde, said the government's right to expel a foreigner is unlimited and absolute. “Intelligence agencies have raised serious concerns about the threat to the country's internal security.”

The order held that refugees are entitled to the fundamental rights to life and equality guaranteed under the Constitution, but the fundamental right to reside and settle in India applies only to citizens.

Gonsalves said the Refugee Convention was the only convention to be considered. There was also the Genocide Convention, which India has ratified.

A three-judge bench, which included Kant, said that Rohingyas, including those with UNHCR cards, would have to be deported if they were found to be foreigners under the Foreigners Act, 1946.

In the 16 May hearing, Gonsalves cited National Human Rights Commission versus State of Arunachal Pradesh and Another (1996), where the Supreme Court’s then-Chief Justice, Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi, tasked the state with protecting the 65,000 Chakmas who had migrated from Bangladesh from eviction and displacement.

Justice Ahmadi ruled that the fundamental right to life and liberty, guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, applies to everyone within the territory of India, both citizens and non-citizens.

Justice Kant said in that case, the union government had told the court that the grant of Indian citizenship for Chakmas was under consideration, and the court's relief was granted in that context. He also said there was a “serious dispute” as to whether Rohingyas were refugees or not.

Criticising the government's stand that India does not recognise the Rohingya as refugees, Gonsalves said, “Now that they have the UNHCR card, the government of India makes the absolutely atrocious statement that we don’t accept these UNHCR cards. UNHCR has been giving these cards for the past 30 years, and they report every single case to the home ministry.”

“When you know refugees are fleeing genocide and you put them back, it is a death sentence,” he said. “You are violating his right to life. How did you do that contrary to international law, Indian constitutional law?”

In response to our query about whether the Indian government had forced Rohingya refugees into the sea on 8 May, Tushar Mehta said he does not speak on any matter other than in court.

“How did India stoop so low?” said Gonsalves. “Once upon a time, Nehru’s sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, was there at the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The UN was so proud. India was so proud. From there to a pariah state where we don’t care for international law, the rule of law.”

What Is Alleged

The petition said that Rohingya refugees were detained overnight at various police stations under the pretext that they would be collecting their biometrics. Some of them were allegedly beaten and pierced with bike keys. Women and children were detained for more than 10 hours without food and without the presence of female police.

A photograph of two people with injuries was attached.

The petition said that refugees were sent to the Inderlok detention centre in west Delhi and then flown to Port Blair, now Sri Vijaya Puram, the capital city of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal, where they were asked whether they wanted to be sent to Myanmar or Indonesia, to which they replied Indonesia.

The petition said that they were forced onto a naval ship blindfolded, with their hands tied. Close to the Myanmar coast, their blindfolds were removed, hands untied, and they were given life jackets and forced into the sea with the assurance that someone would take them to Indonesia.

“Upon arrival, they were devastated to discover they had reached Myanmar,” the petition said.

The petition said children were forcibly separated from mothers.

A 16-year-old girl who was “separated from her family before abandoning her into the international waters”. A female detainee, who contacted a relative in India, alleged that she and others were subjected to sexual assault and groping by officials after detention.

Increasing Number Of Reports

Two days after the petition was submitted to the Supreme Court, Maktoob Media on 12 May first reported the alleged incident. The independent website carried an interview from a Rohingya man who the report said had heard from his cousin, who was pushed into the sea.

On 15 May, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva issued a press release saying that following “credible reports” that Rohingya refugees were forced off an Indian navy vessel into the Andaman Sea, a UN expert has begun an inquiry into such “unconscionable, unacceptable acts”.

The human rights department of the UN urged the “Indian government to refrain from inhumane and life-threatening treatment of Rohingya refugees, including their repatriation into perilous conditions in Myanmar”.

Four days after Maktoob’s report, independent websites Scroll and The Wire reported the same on 16 May, with more interviews from families of people who were allegedly forced into the sea.

Scroll also reported that the civilian National Unity Government of Myanmar, controlled the land where they swam ashore, not the Myanmar army. Officials of the country's civilian-government-in-exile—forced out by a 2021 military coup—told the news website that 40 Rohingya refugees were in their custody.

Scroll reviewed two phone recordings. In one, a refugee alleged that he and others were beaten by Indian officials who accused them of being linked to the Pahalgam terrorist attack on 9 May.

‘Nothing Short Of Outrageous’

In the UN human rights department press release on 15 May, Tom Andrews, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, said that any forced repatriation of Rohingya refugees must end.

“The idea that Rohingya refugees have been cast into the sea from naval vessels is nothing short of outrageous,” said special rapporteur Andrews. “I am seeking further information and testimony regarding these developments and implore the Indian government to provide a full accounting of what happened,” said the special rapporteur.

A UN rapporteur is an independent human rights expert the UN asks to report or advise them from a thematic or country-specific perspective.

“I am deeply concerned by what appears to be a blatant disregard for the lives and safety of those who require international protection,” said Andrews “Such cruel actions would be an affront to human decency and represent a serious violation of the principle of non-refoulement, a fundamental tenet of international law that prohibits states from returning individuals to a territory where they face threats to their lives or freedom”

India has often said it would deport illegal immigrant refugees who do not hold valid travel documents, even though deportation violates the international legal principle of non-refoulement that Andrews referred to, under which countries may not return refugees to countries where they face harm or persecution.

As lawyer Malvika Prasad wrote in Article 14 in February 2020, since India is not a party to the United Nations (UN) Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) and its 1967 Protocol, its refugee protection obligations are limited.

But non-refoulement is regarded as established global law binding on all countries, and the Rohingya are recognised as asylum seekers and refugees by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

India is also a party to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, the Child Rights Convention 1989, and various other instruments that clearly define rights for detenus, especially women and children.

‘...People Sitting Outside Cannot Challenge Our Sovereignty’

On the 16 May hearing, Kant asked for the UN “reports” to be put on the record, saying, “.…all these people who are sitting outside cannot challenge our sovereignty”.

The UN human rights department also mentioned that 100 Rohingya refugees had been removed from the detention centre in the state of Assam and transferred to an area along the border.

The press release said that the special rapporteur wrote to the Indian government on 3 March 2025, “raising concerns about the widespread, arbitrary detention of refugees and asylum seekers, including Rohingya refugees, from Myanmar, as well as allegations of the refoulement of refugees to Myanmar”.

On 10 March, Himanta Biswa Sarma, the chief minister of the BJP-ruled state, said that the deportation of detainees (undocumented migrants from Bangladesh and Rohingyas) from transit centres was almost complete.

Sarma said the state would no longer prosecute undocumented people— “illegal infiltrators”—but “push them back at the border”.

(Betwa Sharma is managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.