Mumbai: In July 2025, soon after the World Bank’s Poverty & Equity Brief placed India fourth among the world’s most equal nations based on consumption expenditure, the government of India’s Press Information Bureau issued a release declaring it a “remarkable achievement”, crediting it to “consistent policy focus” on reducing poverty, expanding financial access and delivering welfare support.

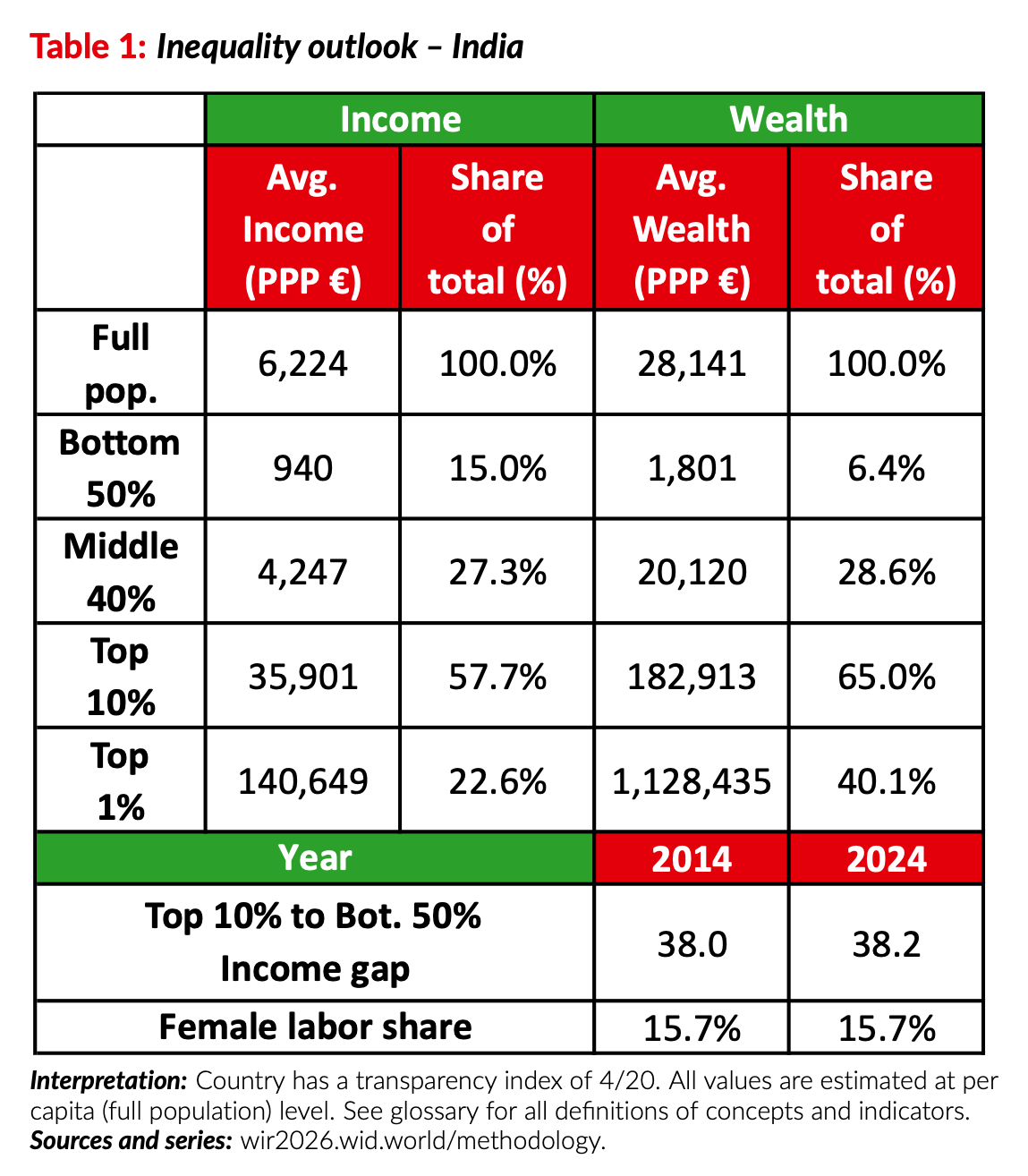

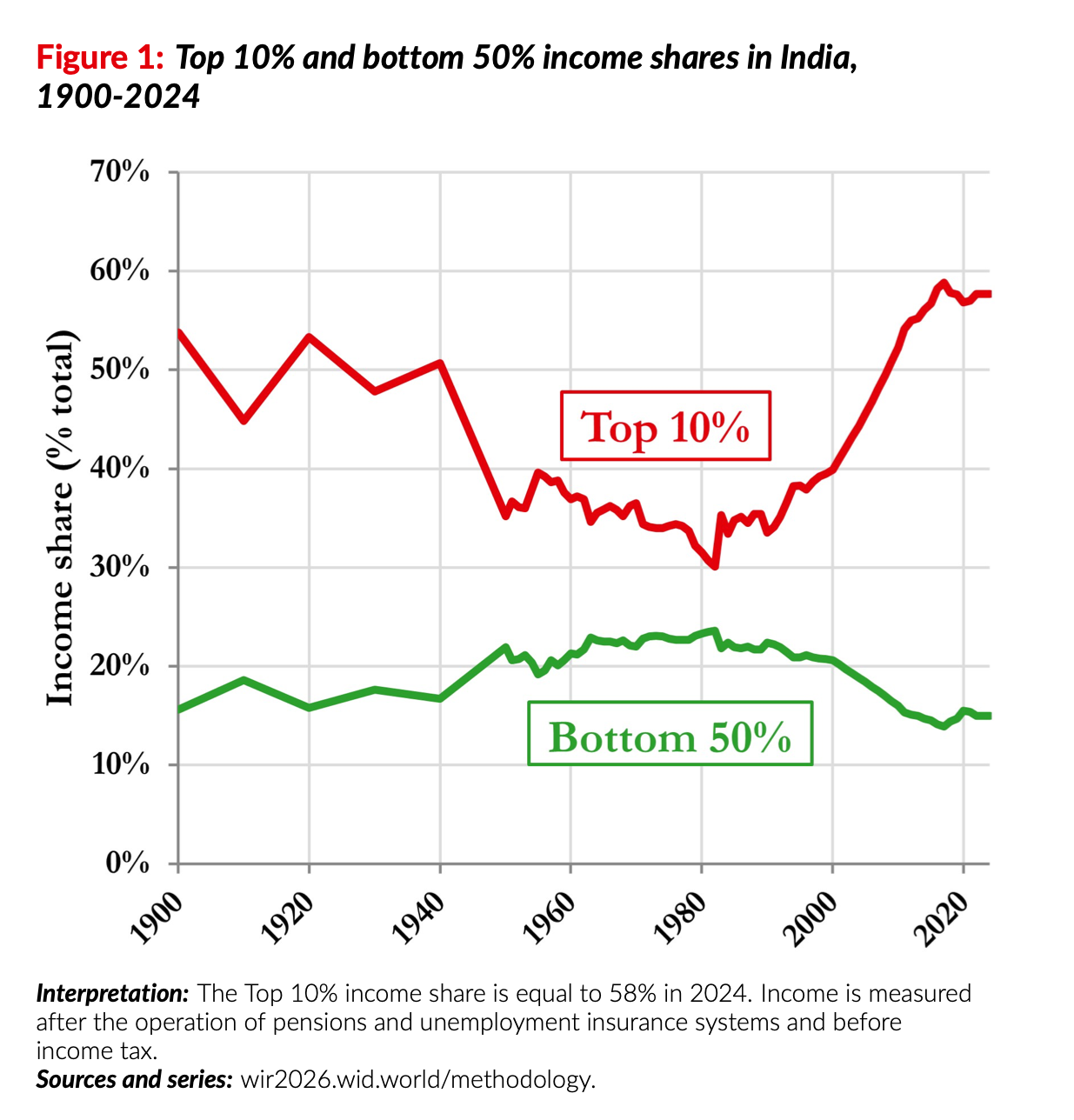

Five months later, the World Inequality Report has said inequality in India is “among the highest in the world”, showing little movement in recent years. The top 10% of earners capture 58% of national income, while the bottom 50% receive only 15%, said the report, released on 10 December. Wealth inequality is worse than income inequality—the wealthiest 10% of Indians hold nearly two-thirds of the country’s wealth; the richest 1% hold 40% of it.

Between 2014 and 2024, this income gap between the top 10% and the bottom 50% remained stable, and women’s participation in the labour force continued to be very low, at 15.7%, also showing no improvement over a decade. The global average for female labour force participation was 49% in 2024. (The government of India claims, however, that female labour force participation is 41.7%, mainly on account of counting self-employed women in agriculture, unorganised work and unpaid work.)

India, home to a sixth of humanity, reflects a global trend on wealth and income.

The report, published by the World Inequality Lab and co-authored by Ricardo Gómez-Carrera of the Paris School of Economics along with French economist Thomas Piketty and others, has found that the top 0.001% of the world’s ultra-rich—fewer than 60,000 individuals—owns three times more wealth than the entire bottom half of the world population combined. These 60,000 people own 6% of global wealth.

Based at the Paris School of Economics, the World Inequality Lab is a research centre focused on the study of inequality and public policies that promote social, economic and environmental justice.

“Extreme inequalities are unsustainable—for our societies and for our ecosystems,” said Lucas Chancel, co-author of the report and co-director of the World Inequality Lab. “Based on four years of work by over 200 researchers on every continent, this report offers a toolbox to inform public debate, to grasp how economic, social and ecological inequalities evolve and intersect—and to drive action.”

Its significance for India lies in what these patterns of inequality mean for long-term socio-economic growth. Research shows that high levels of inequality hamper broad-based growth and citizens’ ability to move up the socioeconomic ladder; income and wealth gaps entrench unequal opportunity, worsen health and education outcomes for the poor, and lock communities into intergenerational disadvantage. Extreme wealth inequalities may distort democratic institutions, as economic power spills into political influence, shaping policy priorities, access to justice, control of the media, etc.

The 2026 report is the third instalment in this series, after previous editions in 2018 and 2022.

In 2024, Piketty and Chancel co-authored Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj, a paper that put into perspective myriad ‘success stories’ on the Indian economy, including projections on GDP growth far exceeding that of any major economy and also higher than the International Monetary Fund’s projections at the time. Their paper said India’s recent years of growth had produced income and wealth inequality; concentration of wealth among the ultra-rich top 1% of people in India is worse than in the US, Brazil and South Africa; and distribution of the spoils of growth was more egalitarian under even the British.

“Inequality is silent until it becomes scandalous,” said Ricardo Gómez-Carrera, lead author of the World Inequality Report 2026. “This report gives voice to inequality—and to the billions of people whose opportunities are frustrated by today's unequal social and economic structures.”

The ‘National Champions’

Increasingly in India, the concentration of economic power has been mirrored in industry too, with market share across several sectors clustered around a very small set of conglomerates.

In 2023, former Reserve Bank of India deputy governor Viral Acharya wrote about the growing footprint of the ‘Big-5’ Indian industrial conglomerates—Reliance, Tata, Adani, Aditya Birla and Bharti Telecom—whose total share of assets in the non-financial sectors rose from 10% in 1991 to 18% in 2021. Industrial concentration fell after liberalisation in the 1990s, but rose in more recent years, supported by a conscious industrial policy of creating “national champions”, Acharya’s paper said. Consolidation by large conglomerates came at the expense of public-sector firms and other private-sector firms.

The average Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) score for eight major industry sectors also jumped to 2,532 in 2024-2025 in India, crossing into the ‘highly concentrated’ zone (score above 2,500), up from 1,980 in FY15 and 2,167 in FY20. The HHI is a tool used to measure market concentration and is commonly used by antitrust regulators to assess how monopolistic a market is becoming.

The World Inequality Report is only the latest in a growing body of research on India’s acutely asymmetrical growth story and its structural imbalances. Civil society organisation Oxfam India’s 2023 report titled Survival Of The Fittest said post-pandemic India’s bottom 50%—roughly 700 million people—received only 13% of national income and owned less than 3% of the country’s total wealth.

A report commissioned by the South African presidency of the G20 in 2024 said India's richest 1% expanded their wealth by 62% between 2000 and 2023.

The 2024 iteration of the UBS Billionaire Ambitions Report said India’s billionaire count more than doubled over the preceding decade, to 185, their total wealth trebling. (The 2025 report said India’s billionaire wealth is holding steady.) Their collective wealth is reported to be in the range of Rs 98 lakh crore, more than the GDP of Saudi Arabia.

Inequality Is Not Inevitable

In her foreword to the World Inequality Report 2026, economist Jayati Ghosh argues that today’s extreme inequality is not a structural inevitability but the outcome of policy decisions.

“Progressive taxation, strong social investment, fair labour standards, and democratic institutions have narrowed gaps in the past—and can do so again,” writes Ghosh, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and previously professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

The authors of the Billionaire Raj paper, Nitin Kumar Bharti, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty and Anmol Somanchi, also suggested, in a May 2024 follow-up note to their paper, reinstating some wealth and inheritance taxation targeted at India’s richest households. Their proposal was for an annual wealth tax and an inheritance tax on those with net wealth exceeding Rs 10 crore, equivalent to the top 0.04% of the adult population (a mere 370,000 adults), who currently hold over a quarter of India’s total wealth.

In a baseline scenario, a 2% annual tax on net wealth exceeding Rs 10 crore and a 33% inheritance tax on estates exceeding Rs 10 crore in value would generate 2.73% of India’s Gross Domestic Product in revenues, they said, adding that explicit redistributive policies could support, for example, doubling expenditure on public education.

The World Inequality Report 2026 echoes this direction, recommending progressive taxation, including wealth taxes on multimillionaires, as a lever for correcting the concentration of economic power.

The 2024 G20 paper by a committee of independent experts led by Nobel Prize winner Joseph E Stiglitz said there was no magic bullet to reduce inequalities, but offered a “menu of prudent policies” including progressive taxation and an international panel on inequality.

Much like governments’ agreed-upon nationally determined contributions to cut greenhouse gas emissions, governments could also commit to national inequality reduction plans with clear goals to reduce income and wealth inequality, it suggested. “Such an approach could eventually aim for the total income of the top 10% to be no more than the total income of the bottom 40%,” the report said.

Taxing The Billionaires

India currently does not have a wealth tax, having abolished it in 2016–17, alongside a broader retreat from wealth taxation across OECD countries between the mid-1990s and 2018. Global conversation has shifted in recent years, however, and taxation of the ultra-rich has re-emerged on political agendas in various parts of the world.

In a 1 December referendum, Switzerland voted overwhelmingly against a proposed 50% levy on gifts or inheritances above 50 million Swiss francs, a measure intended to finance climate and welfare programmes. In the last few months of 2025, several high-profile billionaires in the UK opted to relocate out of the country over concerns about further taxes on the super-rich.

In September 2025, more than 50,000 citizens marched on the streets of Paris calling for proposals to ‘tax the rich’, and against austerity measures in France. Many voiced their support for the proposed ‘Zucman tax’, a 2% levy on assets worth over €100 million, named after economist Gabriel Zucman, a proposal the French parliament rejected in October 2025. Zucman, founding director of the research organisation EU Tax Observatory, completed his PhD in Economics from the Paris School of Economics, under Piketty.

At a July 2024 meeting of G20 finance ministers in Rio, even as the US resisted it, countries agreed to start a dialogue on fair and progressive taxation, including of ultra-high-net-worth individuals. Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva has backed Zucman’s proposal for a 2% levy on billionaires.

In a release, Zucman, scientific co-director of the World Inequality Lab, was quoted as saying the World Inequality Report 2026 provides measures to address income, wealth, gender disparities, regional inequalities and political cleavages within countries. “All these facets of inequality are connected and will shape the evolution of our societies,” he said.

Protecting Capital

In December 2024, at an event organised by a Delhi-based think-tank and the Delhi School of Economics, Piketty said India should take an active role in taxing the rich. Chief economic adviser to the government of India, V Anantha Nageswaran, who spoke at the same event, said higher taxes could lead to capital flight. “Taxing capital less may not make them invest, but taxing capital more will drive away capital,” he said.

In April 2024, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, making comments to journalists after casting her vote in Bengaluru, said an inheritance tax, proposed by the Congress poll campaign, could hit the “middle and aspirational classes”, making the inheritance of savings or small land parcels expensive.

“If such wealth creators are going to be punished purely because they have some money kept behind, India's progress in the last ten years would just go for a zero,” she said.

India cut corporate tax rates in 2019, a stimulus seeking a “multiplier effect in the economy” with anticipated job creation and income growth. Since then, the burden of tax has shifted, and personal income tax overtook corporate tax revenues in 2023-24 for the first time; corporate profits rose nearly threefold from Rs. 2.5 trillion in 2020- 21 to Rs. 7.1 trillion during 2024-25; and corporate profit to GDP ratio (indicating the sector’s health within the broader economy) touched a 15-year high in 2024. Meanwhile, corporate loan write-offs continued, touching Rs 6.15 lakh crore between 2020 and 2025.

Salary growth, on the other hand, remained low (see here, here and here). “While profits surged, wages lagged,” said the Economic Survey of India presented to Parliament in January 2025.

Wages lagged, as did job creation. “A striking disparity has emerged in corporate India: profits climbed 22.3 per cent in FY24, but employment grew by a mere 1.5 per cent,” the report said. It cited a State Bank of India analysis of 4,000 listed companies that recorded a 6% revenue growth, while employee expenses rose only 13%, down from 17% the previous year, “highlighting a sharp focus on cost-cutting over workforce expansion”.

For all the impressive official numbers on economic growth, employment growth has barely moved, widening the gap between rising output and the lived reality of a workforce struggling for stable, decent work.

Agriculture, despite its shrinking contribution to GDP, remains the largest employer of Indians; about 80% of all labour in the country is informal, precarious, lacking social security or job security, and earning low wages. As the Harvard Business Review put it, in the country with the “world’s largest and youngest workforce, there are very few good jobs to be had.”

Gaps Between Policy & Experience

In its press release issued in July on India’s “path to income equality”, the government cited a different set of policies, listing schemes and initiatives that improve financial access, deliver welfare benefits, and support vulnerable and underrepresented groups. Many of those schemes, however, are also faltering on the ground.

For example, while the PM Jan Dhan Yojana is presented as a financial inclusion success story, including a Guinness world records for the most bank accounts opened in a single week, the government has acknowledged that a quarter of all Jan Dhan accounts are inoperative—15 crore accounts, or 26% of of the total 57.07 crore accounts that are meant to give beneficiaries direct access to government benefits.

Also listed as a key policy measure against poverty, Ayushman Bharat, “the world’s largest government health insurance scheme”, is meant to provide health coverage of up to Rs 500,000 per family. The government informed Rajya Sabha on 9 December, however, that more than 2 crore claims amounting to more than Rs 28,000 crore had been settled in the last financial year under the scheme—an average claim settlement of about Rs 14,000.

Article 14 has reported (see here and here) that delayed reimbursement, disputes over treatment costs, cases of fraud, funding shortfalls, and hospitals cutting corners have impaired Ayushman Bharat, with rising demand not matching its claims.

The release said nothing about the sources of inequality, such as market power, caste, spatial discrimination, feeble labour rights, unregulated or poorly regulated extraction by natural resource companies, etc.

“We live in a system where resources extracted from labour and nature in low-income countries continue to sustain the prosperity and the unsustainable lifestyle of people in high-income economies and rich elites across countries,” Jayati Ghosh said, following the release of the World Inequality Report 2026.

These patterns are not accidents of markets, she said. “They reflect the legacy of history and the functioning of institutions, regulations and policies—all of which are related to unequal power relations that have yet to be rebalanced.”

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.