Updated: Jul 16, 2020

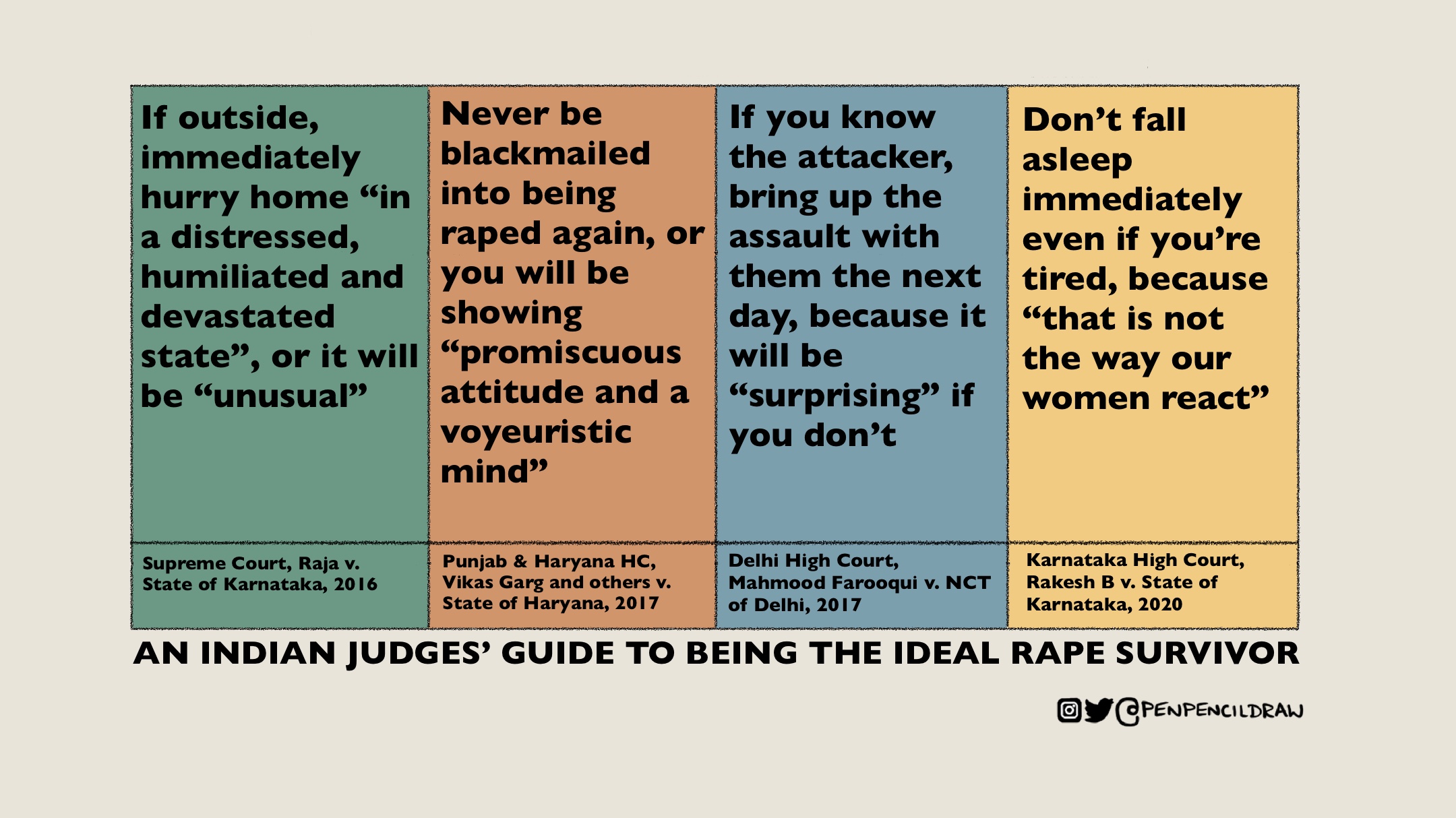

New Delhi: The Karnataka High Court’s observations on 22 June 2020 while granting bail in a rape case follow a judicial tradition of commenting on the behaviour of women, particularly in rape cases, according to an Article 14 review of recent Supreme Court and High Court judgements.

“The explanation offered by the complainant that after the perpetration of the act she was tired and fell asleep, is unbecoming of an Indian woman,” said Justice Krishna S. Dixit in the case of Rakesh B vs State of Karnataka. “That is not the way our women react when ravished.”

The judge appeared also to be swayed by the fact that she was at her office at 11 pm and did not object to “consuming drinks with the petitioner and allowing him to stay with her till morning.”

The remarks sparked a storm of criticism.

In Bangalore, a group of 17 organisations including the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) Karnataka and individuals such as historian Ramachandra Guha and journalist Sharda Ugra, wrote an open letter to Justice Dixit saying his order had “deeply disturbed and disappointed those of us who have been working over the past decades to uproot the discriminatory structures of patriarchy deeply embedded into all our social and political systems including the judiciary”.

In Delhi, advocate Aparna Bhat also wrote an open letter addressed to Supreme Court Chief Justice S.A. Bobde and the top court’s three women judges, Justices R Bhanumati, Indu Malhotra and Indira Banerjee, calling for censure of Justice Dixit’s remarks.

“What is not acceptable, is not acceptable even from a judge,” Bhat said. “We need to call out this misogyny.”

The Supreme Honour of Women

Indian judiciary’s record of comments particularly in cases of rape and sexual assault go back at least to the 1970s. “This is something deep-rooted in society,” said Mrinal Satish, professor at the National Law University, Delhi and author of Discretion, Discrimination and The Rule of Law: Reforming Rape Sentencing in India. The book examined 25 years of rape jurisprudence (around 800 Supreme Court and High Court cases from 1984-2009) to highlight that rape adjudication and sentencing is heavily influenced by rape myths and stereotypes despite legislative reform.

Despite a focus on training and sensitisation of judges since 2013, when the rape laws were amended in the aftermath of the Delhi December 2012 gang-rape and murder, “Rape stereotypes continue, and not just amongst judges but amongst young lawyers and students too,” said Satish.

Very often this bias stems from the idea that the chief harm of rape is the damage to reputation and honour of a woman rather than a violation of her bodily autonomy.

This judicial sanctification of virginity, chastity and honour as a woman’s most prized possession places the burden on victims to resist and signify their lack of consent in ways that would fit the judicial imagination of the ‘ideal victim’: a woman who would, and should, fight tooth and nail to protect what is most precious to her.

It should come as no surprise that according to the Supreme Court, a “rapist degrades and defiles the soul of a helpless female” and inflicts a “serious blow to the supreme honour of a woman, and offends both, her esteem and her dignity” (Deepak Gulati vs state of Haryana, 2013).

This notion of women’s “supreme honour” that “leaves behind a scar on the most cherished position of a woman, i.e. her dignity, honour, reputation and chastity” is repeated in Lillu Rajesh and others vs State of Haryana, 2014.

The idea of the helpless female found in the Supreme Court is echoed by High Court judgments. “The victim of rape grows with traumatic experience and an unforgettable shame haunted by the memory of the disaster forcing her to a state of terrifying melancholia,” noted the Delhi High Court in Rohit Bansal vs State (2015).

In 2015, the Madras High Court, in a highly criticised order, granted bail to a convicted rapist and advised a “compromise” between him and his unmarried victim, who had subsequently become pregnant.

Days before this order was recalled by the Madras High Court, the Supreme Court heard a separate case of the rape of a seven-year-old. There could be no compromise, ruled Justice Dipak Misra as, “Dignity of a woman is a part of her non-perishable and immortal self and no one should ever think of painting it in clay.” (State of M.P. vs Madanlal, 2015).

‘Mind Boggling, Disturbing And A Matter Of Concern’

For reasons unknown and unarticulated, courts, including the Supreme Court, tend to fall back on how a woman who has been raped ought to behave.

“Is there a handbook How to Behave After Being Raped that none of us have read?” asked senior advocate Rebecca John. “You don’t blame a murder victim for provoking her murder. You look at evidence. Why is it so hard to do that for rape victims?”

Rape law is rooted in a landscape of misogyny where the burden of explaining why-she-was-where-she-was falls on the victim. “The judge only has to say, ‘I am not convinced that the prosecution has been able to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt’. Where is the need to go beyond this and comment on women’s behavior?” said John.

Misogyny, said Supreme Court advocate Vrinda Grover, does not begin to capture what is happening in courts nationwide. “There is deep-rooted anxiety about women who are sexually active outside of marriage and a deep-seated suspicion that these women are lying about sexual assault,” she said.

Courts like to play saviour to “good women” in distress, Grover continued. However, where women are in control of their lives, it, “Dislocates and reverses the evolving jurisprudence around rape,” she said.This prejudice plays out at all tiers of the judiciary, she added.

Hearing the bail application (for original order, visit the Allahabad High Court webpage and enter captcha) of former BJP minister Swami Chinmayanand in 2019, the Allahabad High Court said: “A girl, whose virginity is at stake, not uttering a single word to her own parent or before the Court regarding the alleged incident, is an astonishing conduct which speak volumes about the ingeniousness of the prosecution story [sic].”

Justice Rahul Chaturvedi, the judge, found it “mind boggling, disturbing and [a] matter of concern” that the woman student who had accused Chinmayanand of rape “enjoys” his patronage for almost 10 months, during which “she was sharing private moments with the applicant”.

However, the ruling does note that during “this dark period”, the student also purchased a spy camera on which she shot nude pictures and videos of Chinmayanand “which were used by her in demanding the ransom money from the accused applicant [sic].”

Concluding that there was no rape but a “quid pro quo”, the former union minister was granted bail.

Court-prescribed victim behaviour also cropped up in Raja vs State of Karnataka (2016). The Karnataka High Court observed that the victim’s conduct was “not at all consistent with those of an unwilling, terrified and anguished victim of forcible intercourse”.

Acquitting four men of rape, the 2016 order noted that the victim was a woman “accustomed to sexual intercourse when admittedly she had been living separately from her husband for one-and-a-half years before the incident”.

“Instead of hurrying back home in a distressed, humiliated and devastated state, she stayed back in and around the place of occurrence…her confident movements alone past midnight, in that state are also out of the ordinary.” Moreover, one of the accused men had also brought her dosa and idli to eat after the alleged rape, noted the judge.

The absence of injuries on a victim’s body is often seen as proof of her consent. “The medical evidence did not indicate any injury on any part of her body which suggested she was never subjected to any forcible rape,” noted the Rajasthan High Court in 2017 (Rajesh vs State of Rajasthan).

Shaming survivors and using their past sexual history to mutilate their testimonies is common. Granting bail in 2017 to three law students in a sensational case where the three blackmailed a fellow law student to repeatedly rape her, a division bench of the Punjab and Haryana High Court noted that the “misadventure” stemmed from the victim’s promiscuous attitude. The victim stated that one of the rapists “sent his own nude pictures and coaxed me into sending my own”.

But few contemporary rape cases have evoked as much controversy as the acquittal of writer, director and dastangoi artist Mahmood Farooqui by the Delhi High Court in 2017. Farooqui was convicted of raping a woman researcher by a trial court in 2015.

The Delhi High Court could have acquitted Farooqui on grounds that there was reasonable doubt about whether a rape had been committed. Instead it fell back on stereotypes about how vehemently a rape victim must protest. “Instances of woman behavior are not unknown that a feeble ‘no’ may mean a ‘yes’,” the judgment noted. So, even though she had said no, and testified that she had feared for her life, in the eyes of the court, the researcher had not protested strongly enough.

The judgment did not stop there. It noted that different standards of consent would apply since the two were “persons of letters and are intellectually/academically proficient” and have had past sexual contact. Finally, the judgement asked, did the accused understand that the researcher was not consenting?

In other words, the judgment leading to Farooqui’s acquittal cast a doubt over whether the incident even took place, whether the woman had not consented strongly enough and, finally, whether the accused had understood her lack of consent.

Helpless Creature Or Conniving Blackmailer

Women’s groups have fought against the stereotyping of rape victims for over four decades. In the backdrop of this fight, is a judiciary that has stubbornly clung to old notions—women are either hapless creatures whose honour is located in their virginity or they are conniving blackmailers seeking to trap innocent men.

This binary constructs them as either sanctified, sexless and hence, respectable or sexually active, adventurous, promiscuous and undeserving of either respect or legal protection for acts that they must engage in, at their own peril.

As early as 1977, a two-judge Supreme Court bench ruled to acquit three men accused of gang-raping a five-month pregnant woman while she was on holiday at a national park with her partner, a married man. The woman subsequently had a miscarriage.

Noting that the 23-year-old victim was a ‘concubine’, the judges in Pratap Misra vs The State of Orissa ruled that she must have consented since: 1. She had no injuries. 2. She had only sobbed not screamed. And 3. the foetus did not immediately abort.

The ruling came as the famous Mathura case was being heard in various courts. In 1971, a 16-year-old tribal girl named Mathura was raped by two policemen inside a police compound in Gadhchiroli, Maharashtra. In 1974, a sessions court acquitted the policemen noting that Mathura was a “shocking liar” who was “habituated to sexual intercourse” and, so, could not have been raped.

The Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court set aside the judgment; passive submission as a result of fear and threat could not be construed as consent, it ruled.

By the time the case reached the Supreme Court in 1979, a three-judge bench held that Mathura had not raised an alarm and there were no injuries on her body. Because she was used to sex she might have incited the cops “to have intercourse with her”.

The ruling so flew in the face of every principle of natural justice that a group of academics including Upendra Baxi and Lotika Sarkar wrote an unprecedented open letter to the Supreme Court questioning its presumptions of consent.

Women’s groups erupted in street protests and, eventually, the government made changes to the law, invoking stricter punishments for custodial rape and amending the Evidence Act: If a woman says in court that she did not consent, it must presume that she did not consent. The Mathura ruling, however, was never overturned.

The other side of the binary—woman-as-hapless-victim—also has a long history and can be found even in so-called progressive judgments, such as Bharwada Boginbhai Hirjibhai vs State of Gujarat (1983). Affirming that an accused can be convicted solely on the basis of the rape survivor’s testimony, the judge then went on to elaborate differences between the western world and India.

“Rarely will a girl or a woman in India make false allegations of sexual assault,” noted the judge. This is because she is “extremely reluctant to even admit that any incident which is likely to affect her chastity had ever occurred.”

Commenting on the Karnataka High Court ruling granting bail and the comments on ‘our women’ by Justice Dixit, retired Madras High Court Justice Prabha Sridevan said: “So little has changed over the years. Today, you have literature, movies, so much material. Judges should know better, but they don’t.”

Sridevan, an advocate for greater diversity across gender, caste and class in the judiciary, said while inclusiveness is important, she said, “many women would have also thought like this”.

“We don’t care if he was granted bail,” she said. “But the comments on how ‘our women’ would not have fallen asleep after being ‘ravished’, show bias.”

Public space, and that includes the judiciary, has a “male DNA”, said Sridevan. “Unless we reach a critical mass like in the US over the shooting of George Floyd,” she said, “I’m afraid nothing will change.”

(Anupriya Dhonchak is reading law at the National Law University, Delhi, and Namita Bhandare is a member of Article 14’s editorial board.)