Bilariyaganj, Azamgarh: Like any other day, Billal Ahmad had just emerged from the local mosque after offering early morning namaz and was walking back home in Bilariyaganj, a town in the eastern Uttar Pradesh (UP) town of Azamgarh. It was about 5.30 am on 5 February 2020, and daybreak was still some time away.

Along the way, Billal saw two policemen standing some distance away from him.

“The moment I walked past them, they swung into action, encircled me and started hitting me on my legs with their sticks and rifle butts,” Billal, 37, recalled. He asked them why they were beating him.

“But they said nothing, just kept beating me,” said Billal. “I thought of fleeing, but my legs failed, and I fell down.”

They lifted him physically and placed him on the seat of a police vehicle.

Unaware that he was among the last of the Muslim men taken into custody in a police crackdown the previous night on protestors seeking a rollback of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), 2019, Billal haltingly asked the policemen once again what his fault was.

“Wait for a while,” one of the policemen in the vehicle replied. “You will get the answer.”

A daily wage labourer, Billal could see no reason for the assault and detention beyond the fact that he was Muslim. He had not visited the protest site in Bilariyaganj, he told Article 14, appearing to believe that even visiting the site of a peaceful protest, leave alone participating in it, was a crime.

That morning and during the preceding night in Bilariyaganj, citizens were denied their constitutional right to hold a peaceful protest, but what was marked, we found, was the attempt to depict ordinary Muslims as trouble-makers and a threat to the state and society.

Billal and others taken into custody, including a Muslim cleric the police had assigned to defuse the protest, were accused of sedition under section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, in a first information report (FIR), the starting point for a criminal investigation, filed later that day.

Billal, picked up hours after the crackdown from a spot about a kilometre away from the protest site, saw at the Police Line in Azamgarh, a police establishment housing reserve forces’ barracks, that he was not alone, “not the only one arrested because of being a Muslim”. He told Article 14 he realised then that he was part of a group of Muslims who were now to be “condemned as anti-nationals”.

Since Yogi Became CM, Over 1,000 Charged With Sedition

In UP, 77% of the 115 sedition cases filed since 2010 were registered over the past three years, after Yogi Adityanath took over as chief minister, according to an Article 14 database that mines multiple media, legal and police sources to record all sedition cases filed between January 2010 and February 2021.

Our database reveals that of these, more than half pertained to cases of “nationalism”—in which the accused were said to have made “anti-India” remarks or were posting and chanting “Pro-Pakistan” slogans.

This is the first of a two-part series that uncovers patterns in the misuse of India’s 151-year-old sedition law in UP in the context of the anti-CAA protests. The second investigates instances of sedition used by complainants with political affiliations to the ruling party.

These stories also reveal the socio-economic profile of the accused, and the price they have paid to fight these cases. At least one was barely literate, some were students. Many were daily wage labourers or operated small roadside shops, most of them between 20 and 40 years old. All of them spent three to four months in jail.

In February 2021, we reported that sedition cases were filed over the last 10 years against nearly 11,000 individuals. Of these, 2,000 were identified by name, including nine minors. The others, in 816 cases, were “unidentified” accused. Since 2014, the accused have included opposition politicians, students, journalists, authors and academics.

In July 2021, we reported that the Karnataka police had filed more sedition cases than any other state for social media posts. Most of these cases were illegal.

In UP, our data found at least 19 cases filed in relation to allegedly defaming the government in the wake of the Hathras gang rape and murder, and three cases filed against those critical of the UP government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.

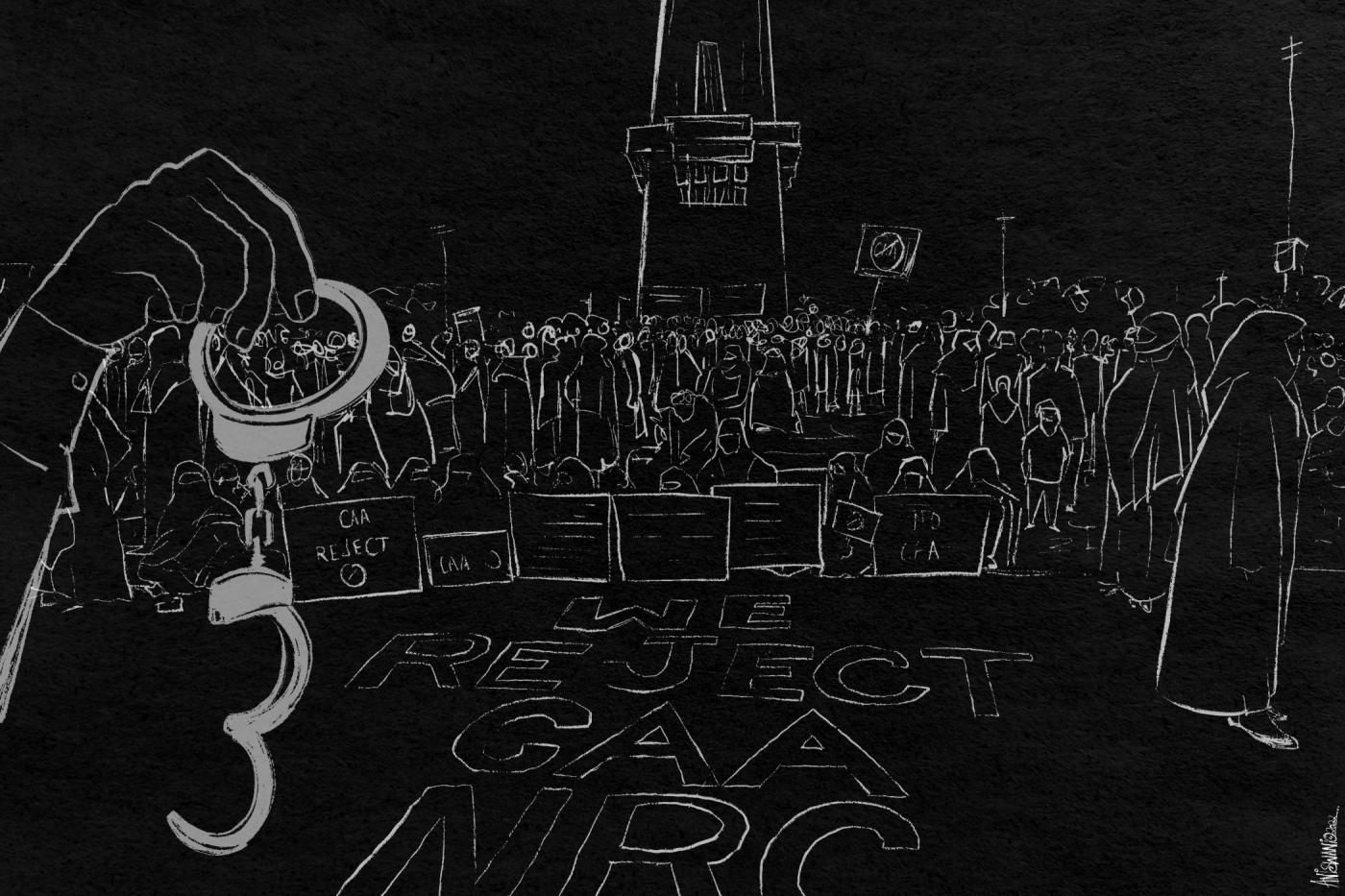

Across India, 3,872 persons were charged with sedition in 26 cases related to the anti-CAA protests between 2017 and 2021. Uttar Pradesh accounted for the largest number of these cases, followed by Assam, Karnataka, Delhi and Bihar.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/02-February/07-Mon/Part%20I_%20Sedition%2BAnti%20CAA%20in%20UP.png]]

Since 2010 in UP, 124 cases have been filed and 1,426 people charged with sedition. More than half of these persons were booked for protesting the CAA. In these 12 years, UP was governed by three political parties, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), the Samajwadi Party (SP), and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

However, after 2017, the year Adityanath was elected CM, more than 1,000 people were charged with sedition—nearly 75% of the total number of persons charged during a decade.

Two Supreme Court decisions, Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar (1962) & Balwant Singh & Bhupinder Singh vs State of Punjab (1962), make it plain that the sedition law can only be used when there is incitement to violence or if there was intention to create disorder. Neither was apparent in any of the cases we investigated.

Closing Down Bilariyaganj’s Shaheen Bagh

Around noon on 4 February 2020, women belonging to the Muslim community began to gather at the Maulana Jauhar Ali Park for a Shaheen Bagh-like protest.

On 15 December 2019, women at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi had started a peaceful sit-in protest against the passage of the CAA. As their peaceful, determined agitation inspired others, several similar protests began in other parts of the country.

The women of Shaheen Bagh inspired the women of Bilariyaganj too, and towards the end of December they began to seek permission from the local administration for a sit-in demonstration. Permission was denied at least three times during December and January.

By the beginning of February 2020, their patience running thin, the women decided to stage a silent agitation anyway. On 4 February, about 25 to 30 of them came out and started a peaceful sit-in at Jauhar Ali Park. By evening, their numbers swelled to about 300, all of them women.

With a population of about 25,000, Bilariyaganj is a block and a town in Azamgarh district’s Sagari sub-division, located about 20 km north of the district headquarters. Muslims account for 60% of its population.

Within hours of the women starting their protest, top officials of Azamgarh district, including district magistrate (DM) NP Singh and superintendent of police (SP) Triveni Singh reached the Bilariyaganj block office, along with bus loads of police from many police stations.

At first, the administration enlisted Maulana Mohammad Tahir Madni, a respected Islamic scholar and resident of Bilariyaganj, to persuade the women protesters to vacate Jauhar Ali Park.

“Around 2 pm that day the DM and the SP started calling me repeatedly, asking me to use my influence to persuade the protesting women to wind up their protest,” Maulana Madni told Article 14. He said they promised to grant permission for a protest on some other day.

With some officials and friends, Madni went to the protest site, where the women agreed to call off their sit-in protest upon receiving a written assurance that permission for a protest on another day would be granted.

“The administration refused to give a written assurance, and the talks failed,” Madni said.

The 63-year-old cleric was forced to make two more attempts that evening, but without an assurance in writing, the women would not back down. Madni returned to the block office and expressed his inability to convince the women.

“I was asked not to leave the place,” he said. “Soon thereafter, I was informed that along with two of my friends who had accompanied me, I had been put under detention.”

After 2 am that night, police swooped in on the anti-CAA protesters and fired teargas shells, dispersing women protesters and picking up over a dozen male onlookers as they started running away.

“As the police raid got underway,” Madni recounted, “Muslims here appeared worried, but not surprised. None of them resisted–they all knew what was happening and submitted to the police obediently.”

The FIR was filed at the Bilariyaganj police station on 5 February. All those taken into custody, including Billal, were slapped with sedition charges.

Maulana Madni was depicted in the FIR as the “instigator and leader” of a “riotous mob” that had gathered at Jauhar Ali Park.

‘It was a hundred percent case of sedition’

“It was a hundred percent case of sedition,” police inspector Rajkumar Singh, the officer who conducted investigations in the case, told Article 14. He refused to respond further, saying that the matter was subjudice.

Presently posted in Ballia in eastern UP, he was attached to the Raunapar police station in Azamgarh at the time of the incident.

Nineteen men were arrested that night, all charged with seditious activity. The FIR also named a solitary woman, Munni Bano alias Kaushar Jahan, who was arrested but not sent to jail, on medical grounds. In the first week of January 2022, she obtained anticipatory bail from the Allahabad high court.

A colonial-era penal provision dating back to 1870, the sedition law was used by the colonial administration to quell political opponents and impede the freedom movement.

Since the BJP came to power in the state in 2017, Uttar Pradesh has not only recorded a surge in registered sedition cases but has also, in tandem with the BJP’s politics of communal polarisation, witnessed an overwhelming majority of sedition cases filed against Muslims.

Irfan Ghazi, an advocate based in Aligarh, said Muslims in UP are caught in a situation where the ruling dispensation was determined to portray them as “traitors” and “trouble-makers”, with the sedition law being a useful weapon to that end.

“How else would you explain the use of this law against peaceful protesters?” he told Article 14. “And how can a peaceful protest against the CAA pose a threat to the sovereignty and integrity of India?”

While section 124A of the IPC says nothing about religion or caste, the government has used it overwhelmingly against one religious community, he said. “Of the few cases of sedition filed against non-Muslims, most are Dalits and OBCs.”

The Article 14 database shows that since 2010, 194 Muslims and 84 Hindus have been charged with sedition in UP. Also, 90% of Muslim accused in sedition cases were charged after 2017.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/02-February/07-Mon/Part%20I_%20Religious%20Affliations%20in%20Uttar%20Pradesh.png]]

Extensive Use Of Sedition Against Anti-CAA Protestors

The protests against the CAA emerged as the single largest issue in which UP witnessed unbridled use of the draconian sedition law.

Anti-CAA protests were organised in several parts of the country since the passage of the law in December 2019. These were mostly peaceful protests, where the Indian Constitution was invoked, the tricolour unfurled and the national anthem sung. While all BJP-ruled states were hostile to the protests, Uttar Pradesh recorded the most vicious and violent incidents as police dealt with the anti-CAA protesters.

The Bilariyaganj incident of February 2020 is only a snapshot.

On 22 March 2020, Fazal Khan, a ward representative of Allahabad Municipal Corporation, was arrested on sedition charges. An FIR filed at the Kareli police station against unknown persons for distributing an unsigned pamphlet on 6 March calling for a protest against the CAA was invoked to arrest him.

“But the police could not produce any evidence to link me with the pamphlet,” Khan told Article 14. He had left Allahabad for Ajmer in Rajasthan on 4 March and had returned on 7 March. Khan was in jail for four months before he got bail.

According to Khan, he was targeted because he actively helped anti-CAA protesters in Allahabad, mostly women, children and senior citizens. Taking a cue from Shaheen Bagh, these protesters had started a peaceful sit-in on 12 January, 2020 at Mansoor Ali Park, which falls in Khan’s ward in the old city of Allahabad.

Busy during the days, Khan helped make arrangements for the protestors and tried to be present at Mansoor Ali Park during the nights, returning home in the mornings.

As in other parts of the country, the Mansoor Ali Park protest ended with the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown on 24 March 2020. On 22 March, the city SP called Khan to his office. “As soon as I reached there, my mobile phone was seized, and I was taken into custody,” he said. “The police neither showed me an FIR nor informed my family about my arrest.”

The accused and their lawyers who Article 14 interviewed said they believed Muslims were slapped with sedition cases because the ruling BJP sought to create communal divisions.

Ghazi, the Aligarh lawyer, said minorities had faced fake cases under previous BJP governments too. “What is different under Adityanath is the rampant use of sedition against Muslims,” he said, adding that even when the sedition charge is not sustainable, it figured prominently.

In Aligarh, police filed multiple FIRs implicating around 1,000 students of the Aligarh Muslim University for protests against the CAA, in December 2019.

More than 20 people across UP had been killed in protests during that time, and the state police were accused of being involved in some of these killings. In Aligarh, around 25 students were badly injured.

Around 100 students, including mainly present and past student leaders, were identified and named in FIRs, while the remaining 900 accused were unidentified.

“In all these FIRs, section 124A of the IPC was used, apart from sections related to attacking policemen, snatching their weapon, obstructing government servants, giving speeches to incite hatred, causing riots and other charges,” Ghazi said.

During investigations, the sedition charge was dropped with the police unable to establish the charge with evidence, and the chargesheet eventually retained most other sections of the IPC except 124A.

“Yet, till the time the chargesheet was filed, the sedition charge remained the most prominent talking point of the case,” the lawyer said.

Dropping Sedition Charge After Damage Is Done

In some cases, by the time the police retract the sedition charge and correct their mistake, the devastation was already done.

At Nautanwa in Maharajganj district in eastern UP, electrician Feroz Ahmad was arrested on sedition charges on 9 November, 2018. He was accused of forwarding a WhatsApp message which the Hindu Yuva Vahini, an organisation set up and nurtured by Adityanath, claimed had hurt the religious sentiments of the majority community.

When the chargesheet was filed, the police dropped section 124A of the IPC, thus clearing the way for his bail from the district court, but the 70-odd days that he had to spend in jail destroyed his business and pushed his family to penury.

Two-and-a-half years after coming out of jail on 29 January 2019, Feroz was still struggling to repay debts incurred by the family in his absence.

Talking to Article 14, a senior police officer in Maharajganj admitted that the sedition charge against Feroz was an error. “When the investigation was done and we realised that a mistake had been committed, section 124A was dropped immediately,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the case.

In the absence of a mechanism to compensate the accused for wrongful imprisonment caused primarily by the inclusion of section 124A of the IPC in the FIR, the dropping of the charge proved to be minor relief.

“I don’t blame the police,” said Saiyyad Feroz Ahmad, a Maharajganj-based lawyer who is Feroz Ahmad’s counsel. “I believe that they are forced to act that way because of the pressure from communal organisations and their leaders.”

While section 124A has been on the statute book since 1860, and from the pattern of its use after Independence, it is apparent that most of them have been registered “during the last seven years” or since 2014, he said.

“Cases filed before 2014 are rare. I don’t have to explain why this has happened during this period,” the lawyer said. “It is self-explanatory.”

Referring to Feroz Ahmad’s case, he said while religious sentiments must be respected, even if Ahmad had been guilty, “what right did the complainants have to pressurise the police to use section 124A in the FIR”?

Declared A Terrorist For Commenting On Yogi

Frequently, the UP police deviated from the core definition of sedition in applying section 124A.

Apart from cases against anti-CAA protesters, they filed sedition cases liberally in instances where Hindutva outfit leaders accused people of hurting the religious sentiments of Hindus, or of posting contents critical of Adityanath.

In February 2021, Article 14 reported that the UP government was particularly harsh on those criticising the government and party leaders, including Adityanath and Prime Minister Narendra Modi: Our data found that 96% of sedition cases filed against 405 Indians nationwide for criticising politicians and governments over the last decade were registered after 2014, with 149 accused in 18 sedition cases of making “critical” and/or “derogatory” remarks against Modi, 144 against Adityanath.

The list of those accused in this manner included former head of the Congress’s digital team Divya Spandana and Aam Aadmi Party member of parliament Sanjay Singh. Spandana tweeted a digitally altered photo showing Modi painting the word chor (thief) on the forehead of his own wax statue. Singh conducted a survey which, he alleged, revealed that the Yogi government was working for a “particular caste”.

In no other state has the sedition law been used so often for criticism of the chief minister or government as it has been in Uttar Pradesh.

Zakir Ali Tyagi, an undergraduate student and a resident of Muzaffarnagar in western UP, was among the first to be booked on charges of sedition for a social media post on Adityanath’s criminal record, soon after he was sworn in.

“My post was based on facts,” recounted Tyagi to Article 14. “It said there were 28 cases pending against Yogi Adityanath, and 22 of them were grave in nature. There was not a single word in the post that was factually incorrect. They were all verifiable facts, available in government records.”

On 2 April, 2017, just 20 days after the new CM’s swearing-in, Tyagi was picked up and kept in the Kotwali police station of Muzaffarnagar city for a day. “In the night, around 2 am, five men—none belonging to the police force—entered the room and started beating me up. They kept saying my life would be destroyed and I would be declared a terrorist because I had commented on Yogi,” Tyagi said.

The policemen did not intervene to protect him, and an injured Tyagi was sent to jail the next day. He was released on 13 May—until then, section 124A was not applied in his case.

“A day after my release, however, I was informed that because of pressure from senior police officers in Lucknow, I would be tried for sedition,” he said. When a chargesheet was filed in his case on 18 May, it invoked section 124A.

Article 14 sought comment from the policemen at Muzaffarnagar city’s Kotwali station who filed the FIR against Zakir or investigated the case, but all of them had been transferred elsewhere.

Abdul Hannan, a Kanpur-based advocate, learned the hard way that sedition cases may be filed based even on complaints from unidentified social media handles.

On 15 March 2020, Shalabh Mani Tripathi, the UP government’s chief adviser for electronic media, tweeted: “Tum kaagaz nahin dikhaoge, tum dange bhi phailaoge, toh hum laathi bhi chalwaenge, gharbaar bhi bikwaenge, aur haan, poster bhi lagwaenge.” (If you do not identify yourself with documents and if you spark riots, we will wield batons, sell your homes, and, yes, we will paste posters too).

It was a tweet targeted at anti-CAA protesters who had called on Muslims not to display their documents during the survey for the National Population Register. Tripathi was referring to Muslims as rioters and justifying the controversial move by the Lucknow administration to put up posters bearing photographs, names and addresses of anti-CAA activists.

Hannan, who offered free legal services to those who had received property recovery notices after participating in anti-CAA protests, replied on Twitter: “Desh ka sabse bada sampradayak aatanki aaj purva padadhikariyon ko aatanki kah raha hai, jaisi karni, vaisi sochani.” (The country’s biggest communal terrorist is today calling former representatives terrorists, as you act, so you think.) He didn’t specify who the communal terrorist was.

The same day, an anonymous Twitter handle— @Limited0190—complained on the microblogging site, and Kanpur’s Kalyanpur police station filed an FIR against Hannan. The FIR, filed by station house officer Ajay Seth, accused Hannan of calling Aditynath a “communal terrorist”, and charged him with sedition. The inspector called him to the police station, said Hannan, for a “conversation”.

“But as soon as I reached there, I was arrested,” he said.

A local court granted Hannan bail three days later with an additional district judge saying it was unclear from his tweet who he was referring to.

Lucknow-based human rights lawyer Ashma Ijjat, accused policemen in UP, from senior Indian Police Service officers to constables, of working on “instructions” from politicians.

“They know nothing else but to follow the instructions of the ruling party,” she said. “The day they start accessing the power provided to them by the law, all the misuse of sedition and other penal provisions will stop.”

These circumstances have made the tenure of the Adityanath government particularly difficult for Muslims.

“After the BJP came to power, minorities in general—including Christians and Muslims —have suffered,” said Ijjat. “But when it comes to Muslims, the attacks become especially vicious. Their objective is not just to inflict bodily harm but to malign the entire community in such a way that others, especially Hindus, start hating them.”

On this fertile ground for polarisation, she said, lay the difference between electoral victory and defeat for the BJP.

This is the first part of a two-part series that examines patterns of sedition cases in Uttar Pradesh between 2010 and 2021. This investigation took place between August and September 2021.

(Dhirendra K Jha is a reporter and writer based in New Delhi. This report was based on data contained in Article 14’s sedition database, A Decade of Darkness. All graphics by Jameela Ahmed.)