Mumbai: As Indians continue to protest about the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, the National Register for Citizens, and the National Population Register, which, viewed together, will put citizenship through a religious sieve and likely send any declared “illegal immigrants” to detention centres, a new book reminds us that this is not the first time India has done this to its citizens.

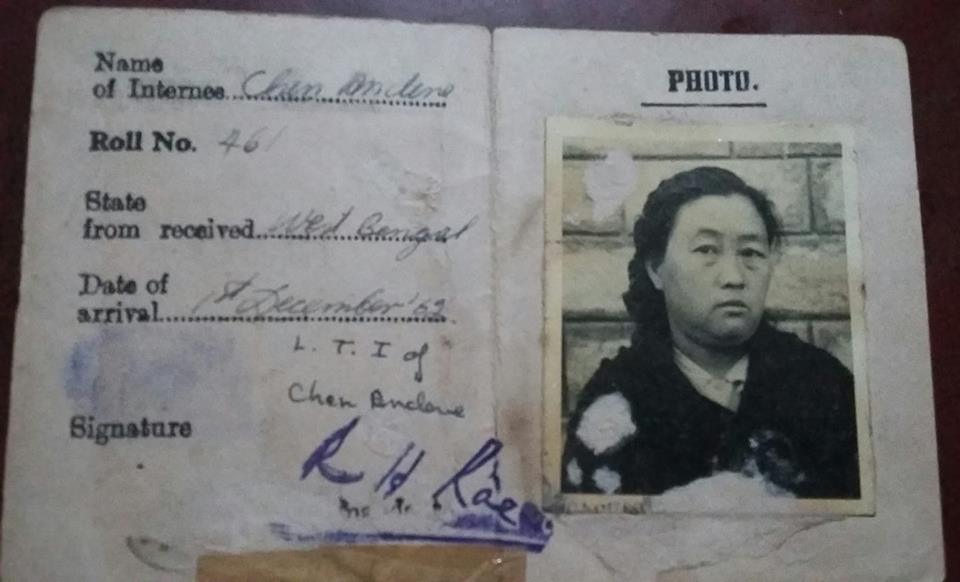

Nearly 60 years ago, at the time of the 1962 Indo-China war, India hurriedly crafted a new legal framework to identify people who could be deprived of citizenship rights. It introduced the Defence of India Ordinance, which made it easy to apprehend and detain people, amended its Foreigners Act, 1946 and passed the Foreigners Law (Application and Amendment) Act and the Foreigners (Restricted Areas) Order. Using these new laws, the country incarcerated 3,000 Chinese-Indians in a camp in Deoli, Rajasthan for up to five years.

This chapter—Foreigners in Our Land—from the recently released book, The Deoliwallahs, examines how India used these laws then.

“Taken together, these various acts were the legal justification to remove plenty of Chinese-Indians from different parts of the country and transport them to the Deoli camp. Let’s be clear: taken together, these acts formed the legal fig leaf for the Deoli incarceration,” write authors Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza.

But official India knew that they needed to craft a legal framework to do this. So in those frantic few months at the end of 1962 and the start of 1963, India gave itself a small flood of new laws. Together, they formed that framework; or, to call it what it amounted to, they formed the legal fig-leaf for this incarceration.

This chapter from The Deoliwallahs examines this fig-leaf.

Leading up to and during the 1962 war – and truth be told, to the present day – Indians saw China as the great betrayer of Nehru’s trust. In fact, Kwai-Yun Li, herself an Indian of Chinese descent, explains in a master’s thesis submitted to the University of Toronto that it was more than betrayal. The Indian government successfully painted the Chinese as ‘a threat to India’s newly-found independence and Indian national security’.

This mindset and rhetoric had serious implications for Chinese-Indians, because especially with the talk of Chinese spies entering the country, they were easily thought of as traitors who were conspiring to help defeat India. Thus, there were large demonstrations against China in various cities, during which Chinese restaurants – or more generally any establishment known to be owned by Chinese-Indians or even with the word ‘Chinese’ in their names – were vandalised. Li writes that Indians even ‘ostracized and sometimes brutalized’ their Chinese-Indian neighbours.

Yet the Indian government kept in mind who the real enemy was, even if ordinary Indians could not always easily tell the difference. They shut down establishments that supported Chairman Mao and his People’s Republic of China (PRC) but allowed those sympathetic to the Nationalist regime in Taiwan remain open. Some of the Taiwan sympathizers knew which side their bread was buttered. Li tells us that they ‘added portraits of Mahatma Gandhi and Indian flags beside Sun Yat-Sen and [the] twelve-pointed star Chinese Nationalist flags’. (In truth, while the Taiwan regime was bitterly opposed to the PRC, it also made it clear that it did not recognize the McMahon line.)

With the country plunged into war, President S. Radhakrishnan promulgated the Defence of India Ordinance (later to become an act) that October. It was specifically crafted to permit preventive detention during wartime. It allowed for apprehension and detention in custody of any person … suspect[ed] … of being of hostile origin or of having acted, acting being about to act or being likely to act in a manner prejudicial to the defence of India and civil defence, the security of the State, the public safety or interest, the maintenance of public order, India’s relations with foreign States, the maintenance of peaceful conditions in any part or area of India or the efficient conduct of military operations, or [whose] apprehension and detention were necessary for the purpose of preventing him from acting in any such prejudicial manner.

Crucially, on 13 November, India also amended its Foreigners Act, 1946, with language that would soon be put to use.

In view of the present emergency, it is necessary that powers should be available to deal with any person not of Indian origin who was at birth a citizen or subject of any country at war with, or committing external aggression against, India or of any other country assisting the country at war with or committing such aggression against India but who may have subsequently acquired Indian citizenship in the same manner as a foreigner. It is also necessary to take powers to arrest and detain and confine these persons and the nationals of all such countries under the Foreigners Act, 1946, should such need arise. [Emphasis added]

Although these lines did not specify what the ‘present emergency’ was, it was clear it referred to the ongoing war with China. Although it did not specify either who ‘any person not of Indian origin’ was, it was clear the phrase referred to Chinese-Indians, especially, and as it turned out not exclusively, those who were still not Indian citizens. Although it does not mention Deoli, that’s where the arrested Chinese-Indians were sent once they were in custody.

There was more to come. Eleven days after amending the Foreigners Act, India passed the Foreigners Law (Application and Amendment) Act. This clarified that the word ‘person’, as used in the Foreigners Act, meant ‘any person who, or either of whose parents, or any of whose grandparents was at any time a citizen or subject of any country at war with, or committing external aggression against, India’. Give a thought to the notion that if a country once fought a war with India, and if your grandparents were once citizens of that country, you might be subject to certain consequences. Like incarceration.

There was still more to come. On 14 January 1963, India passed the Foreigners (Restricted Areas) Order, declaring that people who were defined as ‘foreigners’ could not ‘enter into or remain in’ a number of ‘restricted areas’. These included all of Assam, Meghalaya and five districts of West Bengal.

With one exception, all these laws about foreigners made no mention of Chinese-Indians, the real target in that flurry of lawmaking in late 1962 and early 1963. The exception is the Foreigners (Restricted Areas) Order. Its second paragraph defines a ‘person of Chinese origin’ as someone ‘who, or either of whose parents, or any of whose grandparents, was, at any time, a Chinese national’. Such persons were barred from those designated ‘restricted’ areas in the northeast even if they had lived there for over five years.

Taken together, these various acts were the legal justification to remove plenty of Chinese-Indians from different parts of the country and transport them to the Deoli camp. Let’s be clear: taken together, these acts formed the legal fig leaf for the Deoli incarceration. This was how India justified the internment of a few thousand innocent people, some for up to five years. Because they ‘looked’ Chinese. Because a war spurred many of us to hate our Chinese-looking neighbours. The fallout? Plenty of those people later fled India. Others have spent half a century living in fear that they will be targets again someday.

The fig leaf may have been intended as no more than just a wartime measure, justified or not. But it has had some far-reaching consequences.

The scholar Srirupa Roy explores some of these consequences, apart from the exodus of Chinese-Indians and their continuing fear. The 1962 war, she writes, led to the ‘ethnicization of the nation’, meaning that it became possible to use ‘blood and race’ to define who did and did not belong to the nation. If you were ethnically Chinese, or if your grandparents were, you were not Indian like the others around you were Indian. In fact, as Roy emphasizes, it was even more stringent—‘only one grandparent had to be born in China for the grandchild to qualify as a foreigner’.

And so all this legal language raised questions then that won’t go away easily even well over half a century later. Plenty of the Chinese-Indians who were shortly to be targeted had been born in India. In many cases, so had their parents and grandparents. Even if some of them did not have Indian citizenship, it was because Indian officialdom did not make it easy for them to obtain it. And yet, they had lived in India all their lives and spoke only Indian languages. What made all these people subject to arrest and detention under these new laws? In fact, it’s worth asking: Who is a person of Indian origin, and how do we define that term? How do we define it so as to be able to identify persons not of Indian origin to whom we can apply these laws? Although the legalese did not specify it, to the authorities concerned – and likely to common people too – the answer to these questions were clear in November 1962—people who ‘looked Chinese’.

So it began in 1962. The powers in the legalese, and their implicit message, quickly filtered down to police officers in towns and villages where you’d find Chinese-Indians, people who ‘looked Chinese’. They went after people who travelled to China often, even traders for whom such travel was business; people who corresponded with relatives in China; people, really, with any China connection. For these hapless people, the end of the war was the beginning of years of misery, injustice and uncertainty. For this was the moment – the third week of November 1962, after the guns had actually gone silent on the border – when, across India’s northeast, in Darjeeling and Kalimpong, Tinsukia and Makum, Calcutta and Shillong, and elsewhere, police authorities began rounding up and dispatching Chinese-Indians west to Rajasthan. Yes, the great irony of this strange and tragic episode is that it started largely after the war that prompted it – that made the episode necessary in at least some officials’ minds – was finished. For the suspicion of these people inside India who looked Chinese, and the perception that they posed a grave threat to the country, persisted. Srirupa Roy reminds us that the laws allowed the arrest and detention ‘of any suspicious person’ who fit the definition of ‘foreign person’. Thus plenty of such suspicious people were rounded up; according to government figures, she writes, by February 1963 ‘there were about 2100 detainees in the Deoli internment camp’.

This was exactly what the law allowed India to do: ‘The Central Government may for the purposes of this Order establish internment camps at such places as it thinks fit.’

It’s also worth looking at, briefly, how China considered these events in India. A commentary that broadly presents the PRC’s views on these issues remarked that even those Chinese-Indians who were not incarcerated were affected in various ways. If they lived in the specified ‘restricted areas’, they had to move out of their homes. If they lived outside such areas, they were often forbidden to leave their homes for more than twenty-four hours without a special permit, which ‘handicapped them in their work and their children’s schooling’. Many entrepreneurs had to shut down their businesses. If they were employed in Indian businesses, they were fired. Those who worked in shipyards were no longer allowed even to enter on grounds of national security. There were even some Chinese restaurants, the commentary claimed, that ‘found it prudent to adopt Japanese names’.How helpful this switch in language might have been in evading the attention of hostile neighbours, the commentary did not speculate.

The same commentary also remarked, almost drily, on one unforeseen consequence of these wartime moves. As China sent across a flurry of notes protesting India’s actions, the ‘already bulky Sino-Indian diplomatic correspondence’ grew even bulkier.

It then quotes at length from a paper by ‘one of the PRC’s leading scholars of international law’, Chou Keng-Sheng (also spelled Zhou Gengsheng). Chou accused India’s government of ‘maligning’ China with the claim that China invaded India. This was, he asserted, part of a plan to provoke ‘large-scale anti-Chinese’ sentiment across India, and India’s new laws only reflected this. Chinese-Indians, he also asserted, were generally peaceful and law-abiding. This only cast India’s actions in even more ‘cruel and violent’ light, especially because the fighting on the border could not be used as reason to act against them. Chou also reminded India – perhaps it was even a warning to India – that there were Indian nationals who lived in China, including in regions of Tibet that saw fighting during the war. But did China act against these people, like India acted against Chinese-Indians? No, they ‘continue[d] to have a peaceful and happy life without being arrested and interned’.

Strangely, Chou Keng-Sheng refers repeatedly to those that India incarcerated as ‘Chinese nationals’. He either did not know or chose not to mention that plenty of those arrested were in fact not Chinese nationals. This was possibly even more inexplicable than India’s arrests of Chinese-Indians. For after all, India had to actually amend its laws – so that even grandparents found mention – to find legal justification for its actions, that is, India knew that many of these people were not Chinese nationals.

What did all this do to ideas of nationhood and citizenship in India? Srirupa Roy remarks that it took about two and a half years for the dust to settle, for ‘“normal law” and jus soli criteria of citizenship’ to return. But the episode had changed the country, perhaps irrevocably. What happened with Chinese-Indians in the early 1960s, she suggests, ‘reconfigured’ Indian democracy and the country’s very sense of itself.

Arguably, even several decades later, that reconfiguration persists.