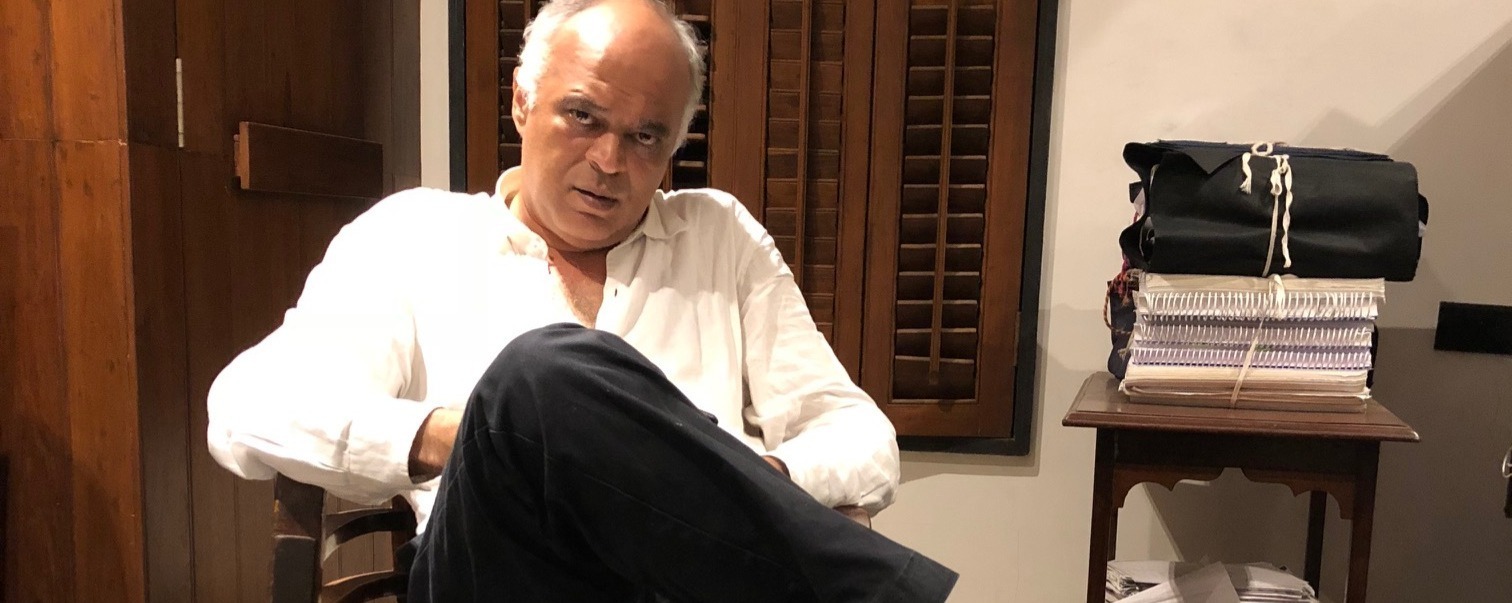

Mumbai: Mumbai-based criminal lawyer Yug Mohit Chaudhry, 52, has been at the forefront of India’s death penalty abolition movement for about a decade now. A scholar of Irish literary revivalism, he taught literature at St Stephen’s College, Delhi, and wrote a seminal book on poet WB Yeats before academia disillusioned him enough to want to pursue a law degree at the University of Cambridge.

In 2001, he began his law practice in Mumbai. Death penalty was a subject close to his heart, and his first post-mercy death penalty case in which the execution was stayed was that of Mahendra Nath Das from Assam in 2011. “We managed to commute his sentence to a life imprisonment,” Chaudhry said when we met recently at his chambers at Fort, Mumbai.

The ongoing atmosphere of fear and hatred isn’t conducive to his work, he says, and the forthcoming hanging of the men convicted of of the gang-rape and subsequent death of a physiotherapy student on 16 December, 2012—Vinay Sharma, Akshay Thakur, Pawan Kumar Gupta and Mukesh Singh—on 20 March is a definite setback.

As of 31 December, 2018, Prison Statistics India, a series of annual statistical reports being brought out by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) lists 402 prisoners on death row—under a sentence of death from a trial court, a high court or the Supreme Court. The last execution was of Yakub Memon on 30 July 2017 for his involvement in the 1993 Mumbai bomb blasts. During his tenure as President from 2012 to 2017, Pranab Mukherjee decided 49 mercy petitions—rejecting 42 and commuting seven to life imprisonment. President Ram Nath Kovind has decided four mercy petitions and rejected all four.

Edited excerpts from the interview with Chaudhry:

You have led the anti-death penalty movement in India for several years now. Has there been a significant change in the way the three cogs in the death penalty system—the police, the judges, and legal aid—operate?

The coming of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government with such force and in such large numbers has made the judiciary far more conservative and right-wing, showing all too clearly that the judiciary is certainly not immune to such influences and pressures. It is said that during the Emergency the executive merely asked the judiciary to bend and the judiciary crawled. Today we are seeing openly-expressed admiration for the prime minister. What business do Supreme Court judges like Arun Mishra and M.R. Shah have to praise the head of the executive? The judiciary and the executive have to exist in very tight tension—that tension has to be maintained, it cannot slacken.

What we are seeing is a cosy bonhomie and a mutual admiration society, which is really in fact a subjugation of one by the other. A related development is the open articulation of right wing views by judges. This was rarely seen earlier. The veneer and fig leaf are gone.

Second, the execution of Memon has spurred the number of death sentences being given across the country. And finally, the December 2012 case, of course, has resulted in a huge spurt in death sentences.

How exactly do these impending hangings have an impact on your work?

This is too overwhelming a case of the judiciary being influenced by a media campaign and public perception. Though the judges call this “the collective conscience of society” it is really only a thinly disguised form of their own personal predilections and prejudices. The judiciary ought not to have any truck with the “collective conscience” at all for it exists primarily to protect individual rights even against majoritarian domination. Further, it has no method or barometer to evaluate the collective conscience.

In this particular case it’s not that there are no issues worth adjudicating. These points have come up in the trial, but they have been glossed over. I can speak about one of the convicts, Mukesh Singh, as I know a little bit about his case. He is wholly undeserving of the death penalty. The death penalty is given in rarest or rare cases and also for the most extreme and culpable role in a particular case. Singh was the bus driver. Initial statements do not attribute any role to him in the sexual assault or violence. He was driving the bus. Later the police realised there was a lacuna and they added his name. It was a very belated afterthought, which in law is considered dubious and consequently ignored. Instead, the judiciary completely ignored the fact that he was belatedly implicated. Not just that, the other persons’ DNAs were found on the victim, but his was not. But it is almost a crime to say that Singh at least doesn’t deserve the death sentence.

So yes, the death penalty abolitionist movement has definitely suffered a setback. The Nirbhaya case has coarsened us all.

Many believe a crime as heinous as this one deserves to be punished with the most stringent of ways and only capital punishment is suitable.

It is a myth that harsh punishment deters crime. In England they used to hang people in public for theft in order to deter it. There were so many instances recorded of people watching these hangings who had their pockets picked. The death penalty is a political gimmick. Politicians use it to show that they are tough on crime. The truth is it allows politicians to get away without doing anything. If politicians were really serious about crimes against women and sexual assault, why haven’t they implemented the Justice Verma Committee Report? The ‘Nirbhaya Fund’ is lying unutilised across state governments.

Just think of it logically. To deter somebody from crime, you need three things to happen, and they have to happen together. There has to be celerity of punishment, severity of punishment and certainty of punishment. If you have two but not the third, there is no deterrence. Suppose you have swift punishment and severe punishment, but you don’t have certain punishment, the criminal will think that he may not get caught. But if there is swift and certain punishment, you don’t need severe punishment to deter because even the prospect of 10 years imprisonment can scare a criminal to stay away from crime.

Many studies have been done all over the world and it has never been proved that capital punishment deters murder more than life imprisonment. I am not saying that it does not have any deterrence value, but it doesn’t have greater deterrence value than life imprisonment.

It is important to ensure that punishment achieves penological objectives, namely general deterrence, specific deterrence, reform and rehabilitation, and finally retribution. If you focus overwhelmingly on retribution, as the line in Hamlet goes, “use every man after his desert, and who shall escape whipping?”

The media as well as the court are presenting the stories of victims and their families. In courts, victims are intervening and demanding harsher punishments. Asha Devi, the victim’s mother is not the only example. There is certainly a failing in us that we have not given enough support to victims of crime. But this cannot be compensated by handing out shotgun justice. It is so distasteful, this desire to “hurry up and execute”.

Are legal aid lawyers better paid now, compared to say 10 years ago?

Legal Aid is just as poorly paid as ever. Since the legal aid system is poorly paid and inefficient, it commands very little confidence among indigent litigants who, ironically, raise whatever money they can to go to a private lawyer who will probably be worse than the legal aid lawyers who will be given to them.

The legal aid system is a farce; a fraud on the Constitution. You have the prosecution being funded by the government, and the legal aid workers are also being funded by the government. They both work on the same case but are paid very differently. You won’t get any lawyer who is willing to do a trial for Rs2,000. In 2011, I had done a study of the balance sheets of the Maharashtra State Legal Services Authority for the period 2000-2009 and found that about 90% of the entire budget was spent on administrative costs, and only about 10% was spent on legal fees. This is a Kafkaesque situation and totally defies logic.

What are the most important landmarks in India's death penalty story?

Very recently, for the first time, the Supreme Court admitted its mistake in a death sentence case. In 2009, in the case of Ankush Maruti Shinde & Ors vs The State of Maharashtra, six people were sentenced to death in a very heinous crime where five persons were killed and two raped. The trial court convicted and sentenced the six accused persons to death, the Bombay High Court upheld the judgement, and the Supreme Court confirmed the verdict and dismissed the review. Their mercy petitions were rejected by the Maharashtra government and were pending with the Centre. With great difficulty, their executions were kept in abeyance. In 2019, through a change in the law, we managed to get the Supreme Court to have another look at the case. And this time the Supreme Court not only reversed the death sentences, but also acquitted them saying that they had been falsely implicated for rape and murder. It also gave them Rs 5 lakh each as compensation for the 16 years they had spent in prison under the shadow of a noose. For the first time, the Supreme Court has admitted to an error in convicting and sentencing an innocent person to death.

For about a year from mid 2018 to mid 2019, there were three judges hearing death penalty cases—Justice Kurian Joseph, Justice Loku Sikri and Justice N.V. Ramana who commuted more than 20 death sentences. Justice Ramanna is still there. In November 2018, Justice Kurian Joseph in his judgement on the Chhannu Lal Verma vs the State of Chhattisgarh case has categorically said that the death penalty should be abolished. He was outvoted on the bench by the other two judges. Nevertheless, this was a very significant moment.

In the case of Shatrughan Chauhan vs Union of India, which we represented, the Supreme Court set a precedent for prisoners to have the right to challenge the rejection of a mercy petition.

Surendra Kohli, the “cannibal of Nithari”, had been sentenced to death by the Supreme Court. And in a brave judgement, on the grounds of procedural irregularity, the chief justice of the Allahabad High Court, Justices Chandrachud and Baghel (of the Supreme Court) commuted the death sentence to life imprisonment. One case against him was struck down because of which he could fight the other 16 cases against him which we took over. The final judgements in eight more cases are still pending and we are expecting a verdict any day now. If he is acquitted, as we expect him to be, it will be on the same evidence based on which the Supreme Court gave him a death sentence.

Another interesting development occurred in the case of Vyas Ram and OthersVyas Ram and Others (2019). In Bihar, the Ranvir Sena, which is the armed militia of the upper caste Bhumiars, had attacked a Dalit village and massacred a large number of Dalits. In response, Dalits attacked a Bhumiar village and massacred a large number of Bhumiars. As it happens so often in our country, the Bhumiars were prosecuted under IPC and the Dalits were prosecuted under TADA. For the first batch of cases that went to the Supreme Court, of Krishna Mochi and others in 2002, they all got the death sentence. Then a second batch (Vyas Ram and Others) came in 2013 on the same evidence and the Supreme Court invoked its former decision in Krishna Mochi’s case to convict them but when it came to the sentence, the Supreme Court refused to give them the death sentence. So it deviated from its own original verdict and gave them a life sentence. The first lot had got the death sentence. The government recommended to the then President Pranab Mukherjee that he reject the first lot’s mercy petition. The President in law is bound by the advice of the cabinet, he can’t go against it. But he went against it. He commuted their sentence to life imprisonment in January 2017, just before he demitted office. The government did not also make an issue out of it. This was a major constitutional moment.

I wish Mukherjee had shown this kind of courage in other cases. Overall, in law, I think it has become more difficult to give a death sentence than it ever was before. But the law isn’t always implemented. In heinous or sensational cases, law is usually the first and biggest casualty. Therefore they say, “hard cases make bad law.”

Non-Homicidal rape offences (i.e. when the victim is raped but not killed) have now become punishable with the death sentence. Isn't that highly problematic?

It is extremely problematic and deeply troubling. The application of the death penalty to non-homicidal rape is very dangerous for potential rape victims.

Macaulay said that when he drafted the Indian Penal Code in 1860, he very deliberately avoided giving the death penalty for rape because he did not want to incentivise the killing of the victim. If a person knows that he will get death sentence for rape, he will think that he might as well kill his victim and finish off the evidence, thereby increasing his chances of acquittal without incurring any greater liability. It is a very dangerous thing to give death sentence for any non-homicidal offences—the Shakti Mills case, for example.

By giving death sentence for rape, we also perpetuate a patriarchal worldview—the Khap Panchayat attitude towards women which believes that if a woman is raped, she is as good as being dead.

What has been your most interesting or heartwarming death penalty case? And what's the most depressing? Among the cases you have been taking on, which one is most unforgettable?

I think the Shindes case is heartwarming. The prisoners were on death row for 16 years. After their release, they came with their extended families to meet me and filled up this whole office. When we took up the case, there was never a doubt in my mind that they were innocent. It takes a lot for the Supreme Court to admit its mistake--it took three very brave judges--and a lot of luck.

One of our most unforgettable cases which we are working on even now is the Kohli case. We say we are married to Kohli. We have been keeping him alive for so many years now. He has been falsely implicated in a case of organ trade by making it appear as if it is a case of cannibalism and he has eaten the missing organs. They found 16 bodies, organs all missing. And they said the lower caste servant ate the organs—one of the most bizarre cases ever. And in the house next door, behind which also bodies were found, lived a surgeon who was formerly implicated in organ trade. The police never interrogated him.

The most depressing cases are the Yakub case and the Afzal Guru cases—here again, the judiciary bent according to public will.

On 11 March, the Delhi High Court directed the Tihar Jail Authorities to consider a request by Zee Media to interview the four death row convicts in the Nirbhaya case and pass a reasoned order the next day. Is it a good idea for convicts to have their say in the media?

I cannot think of any reason why not. However, for the sake of accurate reporting and protecting the prisoner's rights, I would think it a good idea to have the prisoner's lawyer present during the interview.

Even if the prison authorities grant permission, the prisoners still have the right to refuse to grant any interview. In fact, before granting permission, the prison authorities will in all likelihood ask the prisoners if they will consent to the interview.

What is the work of the death-penalty clinic?

The National Law University, Delhi has a death-penalty clinic. They provide legal and other assistance. They do research on the death penalty and intervene in death penalty cases.

We handle cases from all over the country and we teach a regular course at the National Law School in Bangalore on Defending Death Penalty Cases. But we are not a clinic. We are a chamber of lawyers who fund our death penalty work by doing regular criminal law cases.

(Sanjukta Sharma is a Mumbai-based journalist and screenwriter)